Since its settlement in the mid 17th century, the area that is now known as Cambridge has changed significantly. Not only is today’s Cambridge more densely populated, but also its natural landscape has experienced a great deal of reshaping in order to accommodate such changes. Through a careful study of the ground surfaces, their treatment, and reaction to the natural environment we begin to understand how the land was once used, and perhaps how it is meant to exist. Through this paper, I will explore the ways that nature has attempted to creep back into this urban site, and how it is fighting back against the built environment. I will also take into consideration how air flows through the site, and explore how, in the absence of lush green spaces, the different spaces might process the accumulated pollution from cars, buses, and buildings. Exploration of these natural process, can offer us an understanding of how the site once was, and guide us in the future, helping us to develop areas in a way that works together with, rather than against the natural world it exists in.

The site is contained between what is now the Central Square area of River Street, Pleasant Street, Harvard Street, Essex Street, Pearl Street, and Williams Street. Massachusetts Avenue, a highly commercial, and highly trafficked street, slices directly through the center of the site. There are two critically different zones within the site: the tree lined residential zones (pseudo urban green spaces), and the highly trafficked concrete commercial zones. The tree lined residential zones include the streets south of Massachusetts Avenue: Magazine Street, Pearl Street, Green Street, Franklin Street, Auburn Street; as well as Essex Street which is just north of Mass. Ave. The highly trafficked, concrete laden commercial zones include River Street, Mass. Ave, and Prospect Street.

Figure 1 Paved over Parking Zones Underlying map of my site, Google Maps (2014). Retrieved March 1, 2015 from: https://maps.google.com/

Figure 1 Paved over Parking Zones Underlying map of my site, Google Maps (2014). Retrieved March 1, 2015 from: https://maps.google.com/

Today, few public green spaces exist within the confines of the site. Many of the open spaces are paved over parking lots. Despite attempts at paving over these lots, nature has found its way back. I began to look more closely at these paved over sites, counting a total of 5 paved parking lots. (Figure 1) I focused on the three parking lots just to the north of Massachusetts Avenue, the lot on Pleasant Street, and the two lots on the corner of Essex and Bishop.

Figure 2 Large paved over Parking lot on Pleasant Street.

Figure 2 Large paved over Parking lot on Pleasant Street.

The Pleasant Street lot is the largest, (Figure 2) and provided me the opportunity to observe a number of natural phenomena at play with the urban fabric. Surrounding the lot on all sides, are trees. Trees are planted around the periphery of parking lots in an attempt to reduce wind speeds. (Spirn, 80) They are not planted throughout the lot for fear that they may trap carbon monoxide down below. (Spirn, 80) On the side of the lot, along Bishop Street, are five trees, each of which is spaced about four or five meters apart, and stands about three stories high. Along Pleasant Street are 8 trees and their spacing is a bit more erratic. In the center left of the lot are three trees, each of which is three stories tall. The tree bases are covered over in asphalt. Even though the tree bases are not exposed to the elements, the trees appear healthy, and seem to be growing well in their current location. The ground around the trees waves and buckles, this perhaps caused by strong and active tree roots below. Toward the front, center of the lot, the ground becomes increasingly more uneven and buckled, as it funnels down toward a drain. The severe buckling of the surface leading toward the drain has impeded the water’s ability to drain completely, and pools of water have formed on the uneven surface. The buckling of the lot surface is so severe that, as you look out the tops of the cars appear uneven, and tilted to the side. Snow has been cleared to the far right corner of the lot. The snow pile is about one story tall. The right hand side of the lot is far lower than the rest of the lot, and at the moment, drains are not visible. The lack of visible drains makes me question how the site will cope with the melting snow come spring. As I continue to observe the site, I will look for these particular drainage systems, and monitor the buckling of the pavement.

>

Figure 3 Lot on the northwest corner Bishop and Essex, Google Maps (2014). Retrieved March 1, 2015 from: https://maps.google.com/

>

Figure 3 Lot on the northwest corner Bishop and Essex, Google Maps (2014). Retrieved March 1, 2015 from: https://maps.google.com/

>

Figure 4 Lot on the southwest corner of Bishop and Essex.

>

Figure 4 Lot on the southwest corner of Bishop and Essex.

Figure 5 Vines Growing along the fence of a Bishop and Essex (SW) Parking lot.

Figure 5 Vines Growing along the fence of a Bishop and Essex (SW) Parking lot.

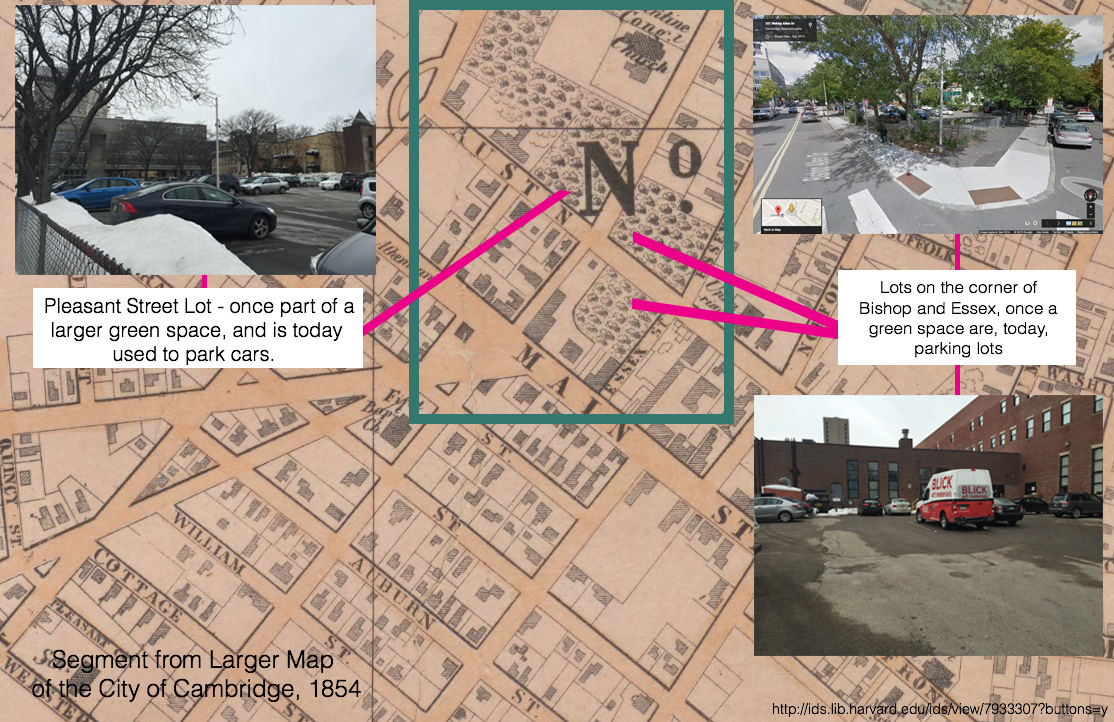

Figure 6 Geo. L. Dix Historic Map of the City of Cambridge from 1854 (http://ids.lib.harvard.edu/ids/view/7933307?buttons=y )with images of what those once green locations look like today. Google Maps (2014). Retrieved March 1, 2015 from: https://maps.google.com/

Figure 6 Geo. L. Dix Historic Map of the City of Cambridge from 1854 (http://ids.lib.harvard.edu/ids/view/7933307?buttons=y )with images of what those once green locations look like today. Google Maps (2014). Retrieved March 1, 2015 from: https://maps.google.com/

Looking at the historical maps of these lots, I began to understand why the surfaces were so uneven, and why plants and trees were trying so hard to creep back in. The lots on Pleasant and Bishop, according to a 1854 Geo. L. Dix map, were originally green spaces. (Figure 6) They appear like wooded areas on 1854 maps.

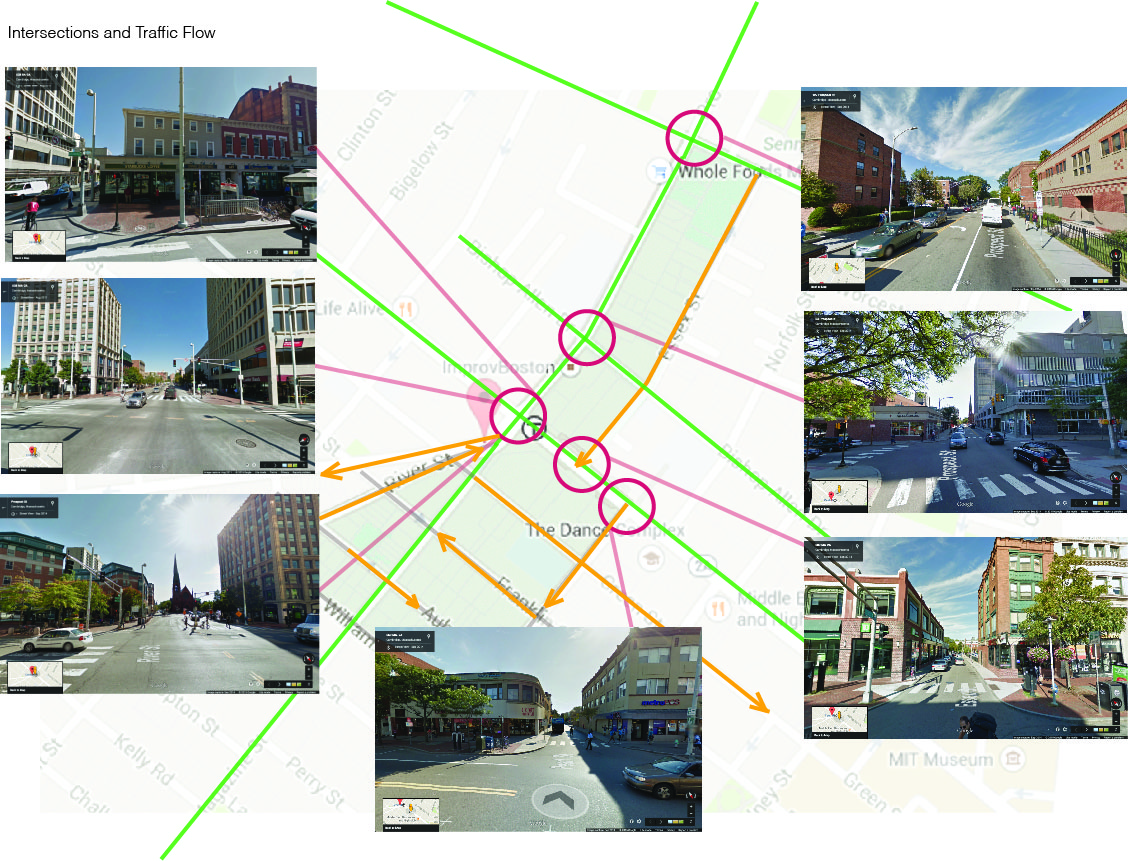

Figure 7: Diagram of traffic flow patterns and images of the busiest intersections Underlying map and Street view images, Google Maps (2014). Retrieved March 1, 2015 from: https://maps.google.com/

Figure 7: Diagram of traffic flow patterns and images of the busiest intersections Underlying map and Street view images, Google Maps (2014). Retrieved March 1, 2015 from: https://maps.google.com/

As I explored the areas around Massachusetts Avenue, Pleasant Street, and Magazine Street, I began to question the different ways that the presence or absence of greenery might affect the air quality throughout the site, and how the flow of traffic through these zones might affect the air quality in these areas. I divided my site into these two types highly trafficked zone and green zones. I then created a diagram indicating traffic flow. (Figure 7) The yellow, indicates one-way traffic, and the green indicates two-way traffic. I marked the heavy traffic flow intersections, and captured Google Street view images of these locations. The streets with the heaviest traffic flow are along the concrete lined commercial zones, and have the fewest trees. Three bus stations are located in the central square zone, which is the intersection of River Street, Mass. Ave, and Prospect Street, and as pointed out, (Spirn, 58) buses and cars often sit idle along the street, awaiting passengers. The only attempt to introduce more green space into the highly trafficked area of Central Square is a small park situated on the corner of Massachusetts Avenue and River Street. The trees and plants were placed in large brick planter seating structures. In the planters, the trees have limited access to the quality earth and light, and have remained small.

Figure 8 Black colored snow on the right side of the street

Figure 8 Black colored snow on the right side of the street

As I moved through these spaces, I began to pay attention to the ways that my body responded to the surroundings, and used this experience as a measure of air quality. As someone with asthma and recovering from pneumonia, I am particularly sensitive to the changes I feel in my breathing when walking between the high traffic commercial zone and the greener residential zone. The air along Mass. Ave. and Pleasant Street becomes much thicker, and I often find myself coughing as buses pass by. Magazine Street, although still a two way traffic street, is subject to far less traffic than River Street, Mass. Ave and Pleasant Street. As I walked along Franklin Street, Auburn Street, and William Street, I could feel my lungs relaxing, taking in the slightly cleaner air. Many of the homes along these smaller streets have large trees in their back yards, and spaces, which I assume, are green and grassy during the summer months. The homes along this street are also set further back from the street, and use bushes or trees as barriers from the street.

Snow is also a good indication of traffic flow. In the areas where traffic was reduced, the snow was a lighter color grey, whereas in the more heavily trafficked areas, such as the bus stops in Central Square; the snow was a dark grey, charcoal color. On one-way streets, the snow tended to be darker on the right side of the street, and upon further observation, I realized the majority of the cars that used the street had their exhaust pipe on the back right hand side of the car. (Figure 8)

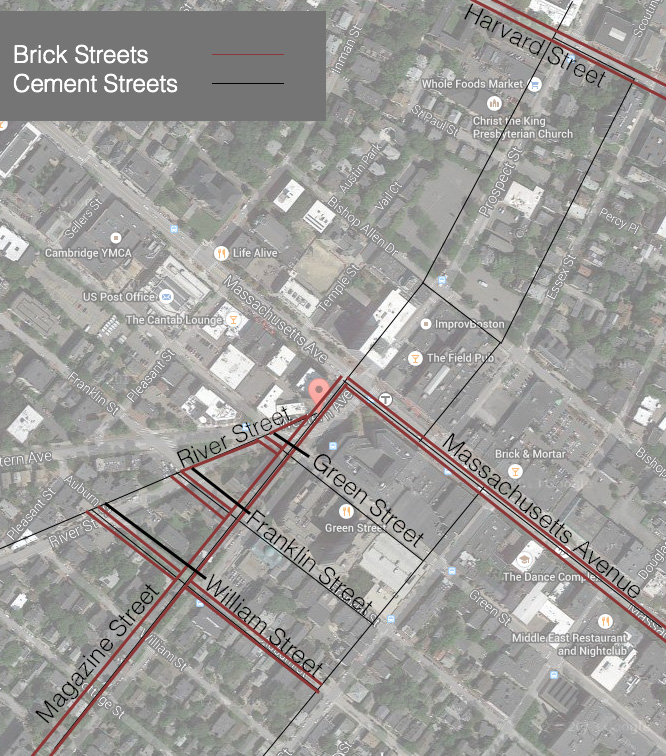

Figure 9: Material type of street; Brick vs. Pavement or Cement Underlying map, Google Maps (2014). Retrieved March 1, 2015 from: https://maps.google.com/

Figure 9: Material type of street; Brick vs. Pavement or Cement Underlying map, Google Maps (2014). Retrieved March 1, 2015 from: https://maps.google.com/

Sidewalk surface texture is another element to take into consideration when thinking about the growth of plants and trees in a particular space. (Figure 9) Brick laid in sand provides far more water to the ground below than cement or asphalt might. The porosity of the brick surface may therefore allow street trees and another plants to flourish. (Spirn, 191-193) A number of the streets in the area just south of Massachusetts Avenue are lined with brick. The trees on the street, although many were planted more recently within the last 10 or 15 years, do appear rather healthy. In this neighborhood of Magazine Street, the space between the street, the sidewalk, and the home is about 6 meters, and provides ample exposed ground yard space for plants to grow. Perhaps the porosity of the brick helps as well, providing more oxygen and water to the surrounding street plants.

Through these observations of surface texture and type, as well as air quality, I began to make sense of the natural processes unfolding on this site. A close study of the now vacant lots, the ground surfaces, their treatment, and reaction to the natural environment, provided a glimpse into the ways that the land was once used, and perhaps how it is meant to exist in the future, as a green space. I observed ways in which trees and plants have attempted to break through these dense, man made surfaces, and creep back into their natural habitat. The presence and absence of trees across the site, as well as the variation in traffic flow presented an interesting variation in air quality, and it was through the reaction of my own body, to the surrounding elements, that I was to deduce air quality, and begin to think about the how these different areas different spaces process the accumulated pollution from cars, buses, and buildings. It is important to understand a site in its totality, not just the people and the business that exist there, but how the earth beneath works to sustain and support the site. In the future, it is important to find ways of allowing nature to thrive in the urban environment. Nature is not a nuisance, but can help to enhance our quality of life, purifying out air, varying and reducing wind speeds. If we take the time to observe the natural processes at work, then we can begin to design more sustainable built environments for the future, working together with nature, rather than against it.

Bibliogrpahy

Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic, 1984. Print.

"Central Square, Cambridge, Massachusetts." Map Data. Google Maps. Google, September 2014. Web 18 February 2015

"Central Square, Cambridge, Massachusetts." Street View Lite Mode. Google Maps. Google, September 2014. Web 18 February 2015