Throughout the course of the semester, I have observed the natural and physical processes that have played out on my Central Square/Cambridgeport site. Through historical maps, I gained insight into the cycles of urbanization, and patterns of densification and commercialization that physically developed throughout the area. As I look at my site today, layers of the past slowly reveal themselves. Proof of social, technological, and architectural movements is found in the form of faded paint signs on the side of buildings, graffiti and street art on Mondica way, and historically preserved homes in Cambridgeport. The traces remind me of the larger social, cultural, political, economic, and architectural movements experienced in the area, both from past and present. As we look at Central Square’s faded past through the clarity of the present, we begin to see traces and connections to the past. Cambridge as a center of intellectual thought and pursuit of education, whether it is in a university setting or a community setting, is just as evident today as it was in the late 1800s. The introduction of mass transportation into Central Square, left its imprint on the community, and altered the demographics of the inhabitants. The individuality of the domestic architectural style may perhaps be reflective of the individual style of Cambridge, and is symbolic once again in its renaissance as an enclave of individual thought and social non-conformity. Through an examination of these changes, it is interesting to note the influence and transformation of such ideas on present day society. The evolution of the site and the physical elements that remain provide us with an idea of the area’s urban cultural values; values which work to inform the neighborhood’s present and future trends in development

As I make my way along Massachusetts Avenue, I find traces of signage: painted letters, graffiti, and billboards along the side of buildings. Some of these faded signs indicate a past commercial identity, while others indicate a particular social and political identity. Cambridge, over the years, has held a strong liberal, education based identity. Light traces of this identity can be found on the sides of buildings today. On the side of 620 Massachusetts Avenue, an art deco/Romanesque style building with a white stone front, and brick side, I find traces of the buildings past commercial identity. The side of the building, although barely legible today, reads (Figure 1) :

Figure 1 - Prospect House Building (620 Mass. Ave) – Faded white paint on the side of the building potentially reads - “PROSPECT HOUSE/ BOATING/ AND/ BAITING/ STAPLES”

Figure 1 - Prospect House Building (620 Mass. Ave) – Faded white paint on the side of the building potentially reads - “PROSPECT HOUSE/ BOATING/ AND/ BAITING/ STAPLES”

“Prospect House,” can be found in an 1891 edition of the Cambridge Tribune, and States. The small blurb in which it appears, states that “the first fall meeting of their Prospect Progressive Union will be held at their rooms in the Prospect House September 22.” The Prospect Progressive Union was a men’s education center, which rented two floors of the Prospect house. Today, the upper floors of the Prospect House Building (620 Massachusetts Avenue) are home to a number of offices, and the street fronts are home to a Dunkin Donuts and Bank of America. The uppercase font on the side of the building remains as a trace of the building’s previous life and inhabitants.

Despite gentrification, Cambridge remains home to a number of smaller community-based learning centers. Along Mass. Ave., we see a trace of the community based education culture. Heading toward Boston, outside of the scope of my site, you can find the Business Community Education Center and the Marxist Community Educational Center side by side. (Figure 3) This idea of educating the public outside of the formal degree system – in a community based environment seems to have taken hold in Cambridge and one can see its roots in 1891, with the Prospect Union House.

Figure 2 – Marxist Community Educationa Center and Camrbridge Community Business Education Center. Google Earth, 2014.

Figure 2 – Marxist Community Educationa Center and Camrbridge Community Business Education Center. Google Earth, 2014.

Following the introduction of the redline system in the early part of the 1900’s, Central square experienced a great deal of economic decline. Within this decline, however, flourished a vibrant alternative, and somewhat rebellious community. In conversations with Cambridge residents, some recall a time in the 1980s and 90s when you would see punks walking through Central Square, wearing studded leather jackets, and their brightly died blue, green, or pink hair jelled into a shark Mohawk. In recent years, however, patterns have shifted and gentrification has altered many of the commercial and residential spaces. On Massachusetts Avenue, mixed in between the Café 1369, cheapo records, and an astrological bookstore, you now find regional and national stores like CVS, Walgreens, Blick Art Supply, Dunkin Donuts, and Starbucks. The shift in store types has brought with it a shift in clientele.

Bars and restaurants are an example of the changing social, political and economic makeup of those that inhabit Massachusetts Avenue in Central Square. In and around Central Square, you can find anything from sports bars like “Tavern on the Square,” (outside of site) to more alternative bars like “People’s Republic,” (outside of site) and trendier, “hipster” bars, like “Brick & Mortar.” Bars are the social spaces of a community, they are the places where people gather together to talk, eat, and drink. Each bar and restaurant in Central Square caters to a varied group of people, from sports types to alternative socialist. The variation in bar types is reflective of the variation in the people that today inhabit this space of Central Square, and are indicative of the social, political, and economic diversity of the area.

Traces of Central Square’s alternative past still remain, in particular, in the form of graffiti and street art. Graffiti is a symbol of alternative movements. It began in New York in the early 1960s, and by the1980s it had grown and evolved into what we now recognize as “street art.” Many street artists today, create works that force the viewer to question social, political, and economic reality. More recently, street art has become a highly popularized movement, and is recognized and lauded by some of the largest art world institutions. Along Mass Ave, we get a glimpse of this idealized notion of something that once stood as a symbol of alternative culture. Along Mass. Ave, wedged between Central Kitchen and Citi Bank you find Mondica Way, an alleyway dedicated to street art and graffiti. (Figure 3) The posters, tags, and murals on the walls change and grow from week to week. The wall is three stories tall, and a line of tags and posters coat the top edge of the building. Along the top edge of the building are two white on black posters. The posters depict a camera with a flash going off. Below the image of the camera, written in bold white text are the words, “THE POLICE.” At first, the images seem harmless, but then you ask yourself, what do you do with a camera? You “take,” “snap,” or “shoot” pictures. The poster can read, “Shoot the police” (Figure 4) These posters speak to the social and political views of those that continue to inhabit the space, and the values they may share when it comes to their relationship with the large government institutions.

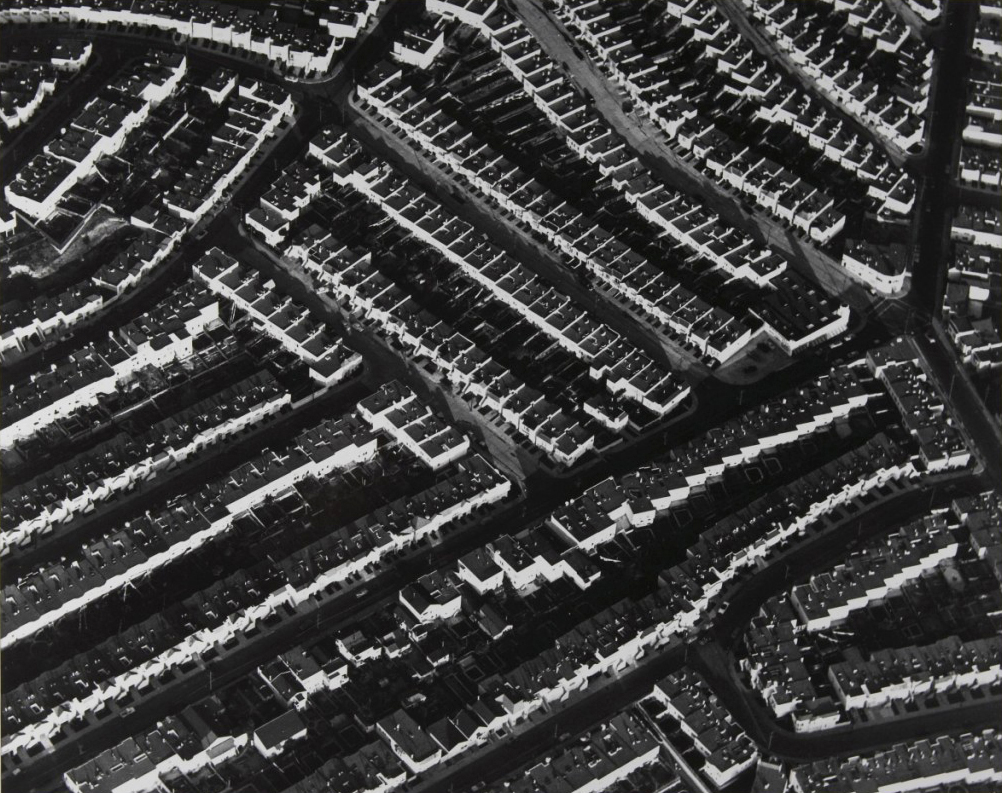

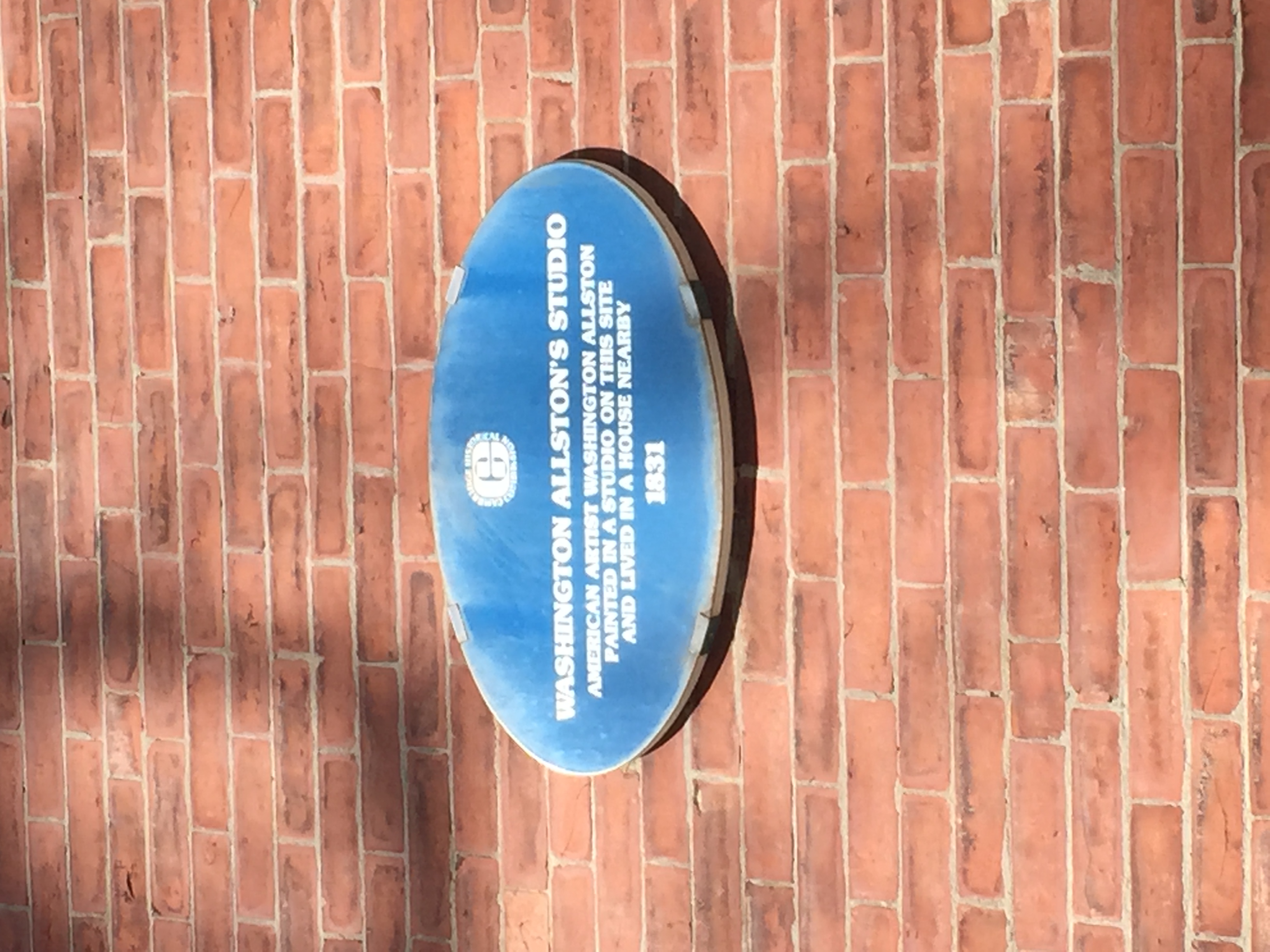

Mondica Way is in itself a kind of contradiction. Graffiti developed as an alternative movement, and found its home in Central Square. It presence was closely tied to the rebellious alternative identity of Central Square throughout the 1980s, 90s, and early 00s. The “Shoot the Police” posters are the most direct remnant of this rebel alternative culture. However in recent years, as the community has gentrified, the graffiti has become a symbol of the area. In creating the alley, the particular place where people would tag, the work is placed on an idealized, contained pedestal. It is no longer free to roam. It becomes a contained rebellion, if that is even possible. The current generation Z was raised in a social and educational climate that “encourages individualism and appreciation of diversity.” Creative identity, and notions of freedom of expression which are closely tied into the creative community, seem to attract members of generation Z. However, we do not all seek difference in that that is new, and that which is newly created. We have, it seems, also reverted to the past in our search for individuality. This is most readily observed in the domestic architecture in the Cambridgeport neighborhood. Perhaps, this search for individuality is the result of the growing up exceedingly homogeneous American suburbs. Not only did people live around people similar to themselves, but also the architecture they inhabited was often equally as homogenous, and mass-produced (Figure 5). Perhaps, as people shift toward a more urban setting, they are seeking quirky, individuality in the space they inhabit. A number of these homes were designed and constructed in the mid to late 1800s, and over time, the homes, and the plots were subdivided into smaller lots. The homes are laid out in sometimes-strange ways, with one house sitting in the backyard of the other. These quirky layouts however are a mark of time, a mark of fewer regulations, in planning and design. They also provide a sense of individuality and difference to the neighborhood – breaking with the perfectly spaced, perfectly aligned homes of more contemporary American suburb. The homes of Cambridgeport hold value in difference, and value in age. The Cambridge Historical Commission has identified many of the homes in Cambridgeport neighborhood, as historic landmarks, and you can see this as you walk around the neighborhood. Small, blue ovals on the sides of homes indicate when the home was built and provide information about who lived there. The homes of Cambridgeport hold value in difference, and value in age. The Cambridge Historical Commission has identified many of the homes in Cambridgeport neighborhood, as historic landmarks, and you can see this as you walk around the neighborhood. Small, blue ovals on the sides of homes indicate when the home was built and provide information about who lived there. As you walk though the neighborhood, you can see the various architectural layers of colonial era homes, Victorian era homes, triple-decker flats, and modern condominiums. Within the confines of my site are two buildings that have been identified as historical landmarks. The first is the artist, Washington Allston’s studio in a brownstone on Magazine Street. The studio space is identified by a Cambridge Historical Commission plaque that reads “Washington Allston’s Studio: American artist, Washington Allston painted in a studio on this site and lived in house nearby (1831).” (Figure 6) The statement on the plaque is vague and des not directly identify the studio space, but only that it once existed on this site. Perhaps the original building was removed or altered to the point where the studio space no longer exists. The second space is Washington Allston’s home just across Magazine Street, on Auburn Street. A large plaque marks the site of the home, and informs passersby of that the artist that once lived there. (Figure 7)

Architectural details on homes are artifacts that can provide us with clues in understanding the community’s social, cultural, or historical past. Roof design is one such artifact that reveals the social and economic status of a neighborhood. Throughout the Cambridgeport neighborhood you find a number of homes with Mansard roofs. (Figure 8) The roof type became trendy throughout the mid to late 19th century. Used as the roof design style in Haussmann’s Paris, the mansard roof was a symbol of modernity and progress. When it was later imported to the United States, it became a signifier of a wealthier class, and was used in the design of elegant mansions and homes. This roof design is found on a number of homes in Cambridgeport. (Figure 9) The homes vary in size from two three or even four stories in height. As we move through the Cambridgeport neighborhood, the built environment exposes us to a number of social, cultural, political and economic layers of time. As the community continues to gentrify, it is important to take into consideration what will happen next; how the city will grow and how it will change. Those that are redeveloping the community are not those that have been living there for the past 30 or 40 years. These new inhabitants highlight that which they like and discard that which they do not. In this process of urban editing, the discarded elements are sometimes the key components of the area’s identity. As Central Square inhabitants and user groups change, it risks becoming a homogenous urban center. As individuality becomes an increasingly sought after trait among future generations, so too will the traits that make places special and different. We must be wary of flushing out individual identity, and creating a placeless urban environment. Bibliogrpahy - Cambridge Historical Commission, Cambridge Massachusetts. - "Individualism for a New Generation." NYTimes.com. 24 Sept. 2007. Web. 28 Apr. 2015. - Lewisohn, Cedar. "Street Art at Tate Modern." The Tate Modern. April 2, 2008. Accessed April 25, 2015,. http://www.tate.org.uk/about/press-office/press-releases/street-art-tate-modern. - O, J. H “Interview with Cambridge Resident.” Telephone Interview. 21 Apr. 2015 - Spirn, Anne Whiston. “In Class - Walking Field trip of Cambridge.” 15 Apr. 2015. - Spirn, Anne. "Timeline." Once and Future City. Massachusetts Institute of Technology School of Architecture and Planning, 1 Jan. 2012. Web. 1 Apr. 2015.  Figure 3 - Mondica Way, Central Square Cambridge. Graffiti Alleyway

Figure 3 - Mondica Way, Central Square Cambridge. Graffiti Alleyway

Figure 4 – Shoot the Police poster on Mondica Way building roof line. April 5, 2015.

Figure 4 – Shoot the Police poster on Mondica Way building roof line. April 5, 2015.

Figure 5 – Aerial view of the homogenous American suburban layout. William A. Garnett, American, 1916–2006: Housing Development, San Francisco, California, 1953–56. Gelatin silver print, 39.6 x 49.5 cm. Gift of David H. McAlpin, Class of 1920(x1971-261). © 1953, Estate of William A. Garnett. http://puam.princeton.edu/lifeanddeathofbuildings/section/houses/garnett

Figure 5 – Aerial view of the homogenous American suburban layout. William A. Garnett, American, 1916–2006: Housing Development, San Francisco, California, 1953–56. Gelatin silver print, 39.6 x 49.5 cm. Gift of David H. McAlpin, Class of 1920(x1971-261). © 1953, Estate of William A. Garnett. http://puam.princeton.edu/lifeanddeathofbuildings/section/houses/garnett

Figure 6 – Plaque indicating Washington Allston’s Studio on the side of Brownstone. Brownstone is located on Magazine Street, Cambridge, MA. Sign provided by the Cambridge Historical Commission

Figure 6 – Plaque indicating Washington Allston’s Studio on the side of Brownstone. Brownstone is located on Magazine Street, Cambridge, MA. Sign provided by the Cambridge Historical Commission

Figure 7 – The Brownstone where Washington Allston's Studio is located. Magazine Street, Cambridge in Cambridge, MA. Blue sign provided by the Cambridge Historical Commission is on the left hand-side.

The plaque serves as an educational tool, providing us with details about his personal, and professional life as a painter. The introduction of the plaque provides us with the social and economic identity of the man that once inhabited this neighborhood. It provides us with an idea of how this object and space were originally used, and who used them. Today, the home and studio stand as a timepiece, fitted into the modern urban context. The plaque serves as a reminder of when the home was build, and identifies the home as a modern day, socially significant artifact to observe. The plaque also serves as an artifact of our modern day social and cultural values. Through the use of the plaque, we begin see value in this home. Unlike the surrounding homes, this one has been made to stand apart from the rest. Through the placement of the sign, the Cambridge Historical Commission is telling us that it is culturally significant. They are highlighting the artist as valuable to Cambridge’s social, creative, and intellectual history. Signs in this context, serve as an artifact of the social and the cultural context for which they are made, and help to identify the studio and homes as a valuable artifact. We do not need such signs in order to understand the identity the home as an artifact, but the addition of the sign seems to add to this artifactual quality. The addition of the sign increases the homes social value, but what if they placed a plaque on every house and identified those that lived there?

Figure 7 – The Brownstone where Washington Allston's Studio is located. Magazine Street, Cambridge in Cambridge, MA. Blue sign provided by the Cambridge Historical Commission is on the left hand-side.

The plaque serves as an educational tool, providing us with details about his personal, and professional life as a painter. The introduction of the plaque provides us with the social and economic identity of the man that once inhabited this neighborhood. It provides us with an idea of how this object and space were originally used, and who used them. Today, the home and studio stand as a timepiece, fitted into the modern urban context. The plaque serves as a reminder of when the home was build, and identifies the home as a modern day, socially significant artifact to observe. The plaque also serves as an artifact of our modern day social and cultural values. Through the use of the plaque, we begin see value in this home. Unlike the surrounding homes, this one has been made to stand apart from the rest. Through the placement of the sign, the Cambridge Historical Commission is telling us that it is culturally significant. They are highlighting the artist as valuable to Cambridge’s social, creative, and intellectual history. Signs in this context, serve as an artifact of the social and the cultural context for which they are made, and help to identify the studio and homes as a valuable artifact. We do not need such signs in order to understand the identity the home as an artifact, but the addition of the sign seems to add to this artifactual quality. The addition of the sign increases the homes social value, but what if they placed a plaque on every house and identified those that lived there?  Figure 8 –

Figure 8 – Figure 9 –

Figure 10 – Home with paved over front yard on William Street Cambridge, MA. Photo taken April 19, 2015.

Figure 10 – Home with paved over front yard on William Street Cambridge, MA. Photo taken April 19, 2015.

Figure 12: Two homes in the Cambridgeport neighborhood that are visibly underconstruction. One in the process of being built the other under renovation.

Figure 12a: Two homes in the Cambridgeport neighborhood that are visibly underconstruction. This home is in the process of construction.

Figure 12b: Two homes in the Cambridgeport neighborhood that are visibly underconstruction. This home is under renovation.

Figure 12b: Two homes in the Cambridgeport neighborhood that are visibly underconstruction. This home is under renovation.

Figure 12 – Construction permit on display in the window of a Cambridgeport home. Photo taken April 19, 2015.

Figure 12 – Construction permit on display in the window of a Cambridgeport home. Photo taken April 19, 2015.

Figure 13 – Restored home on Magazine Street in Camrbidgeport, MA with landscaped front yard. Photo taken April 19, 2015.

Figure 13 – Restored home on Magazine Street in Camrbidgeport, MA with landscaped front yard. Photo taken April 19, 2015.