A city cannot be separated from its location. Nor can a location truly be separated from its city. In this way, it is unsurprising that natural forces directly influence the development, existence, and future of the urban landscape. Evidence of this give and take manifests itself in both the historical context of the site and the ongoing conflict between the man- made landscape and the natural world that shares this space. Study of this stand-off finds cases of both severe tension and harmonious coexistence. Natural forces and processes have nearly written the story of my site for the past, present, and future. From these illustrative examples, one can draw an understanding of an ideal relationship between the natural and urban environments, one that broadly and simply addresses the question of coexistence for the urban future.

Past

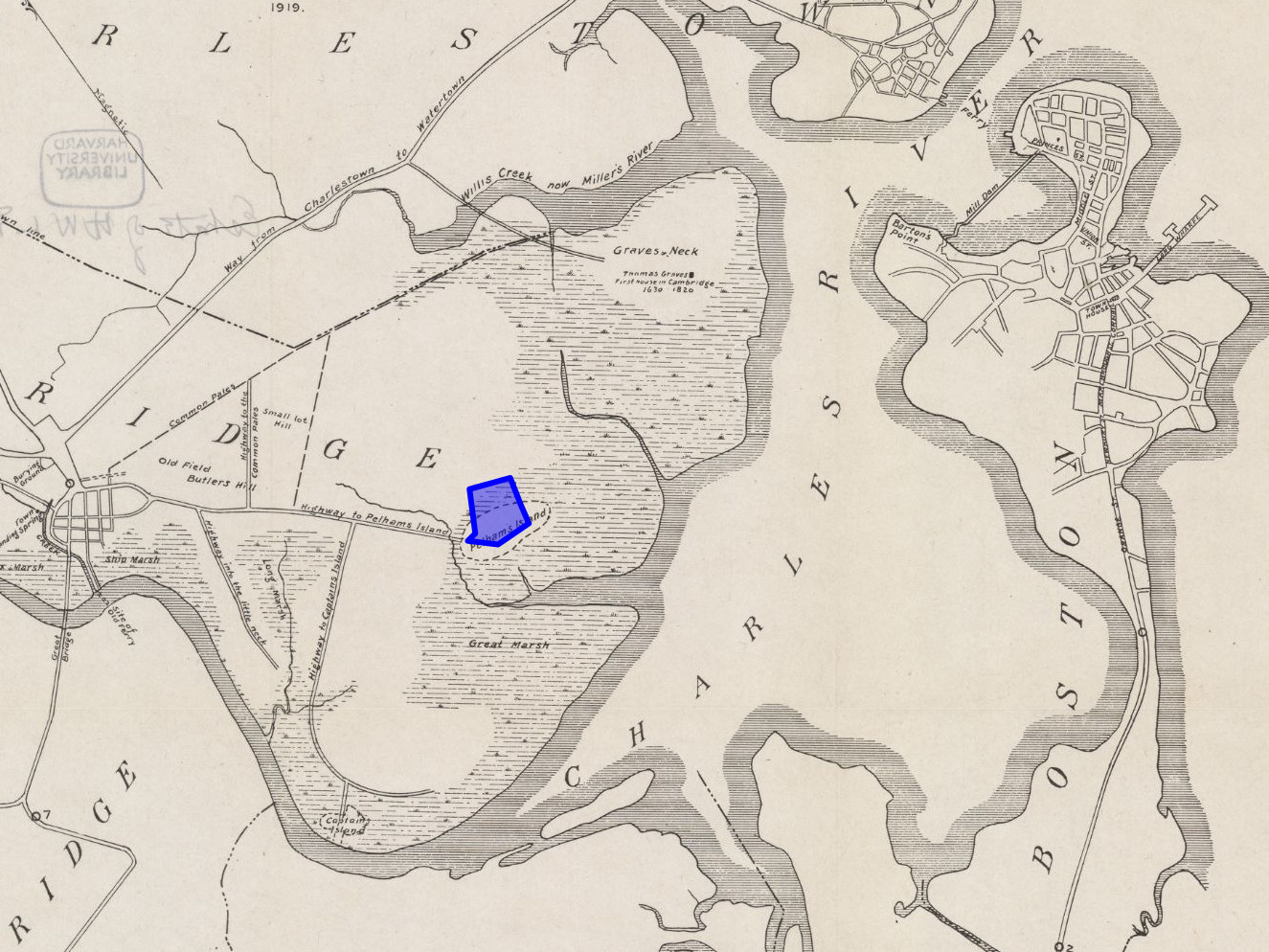

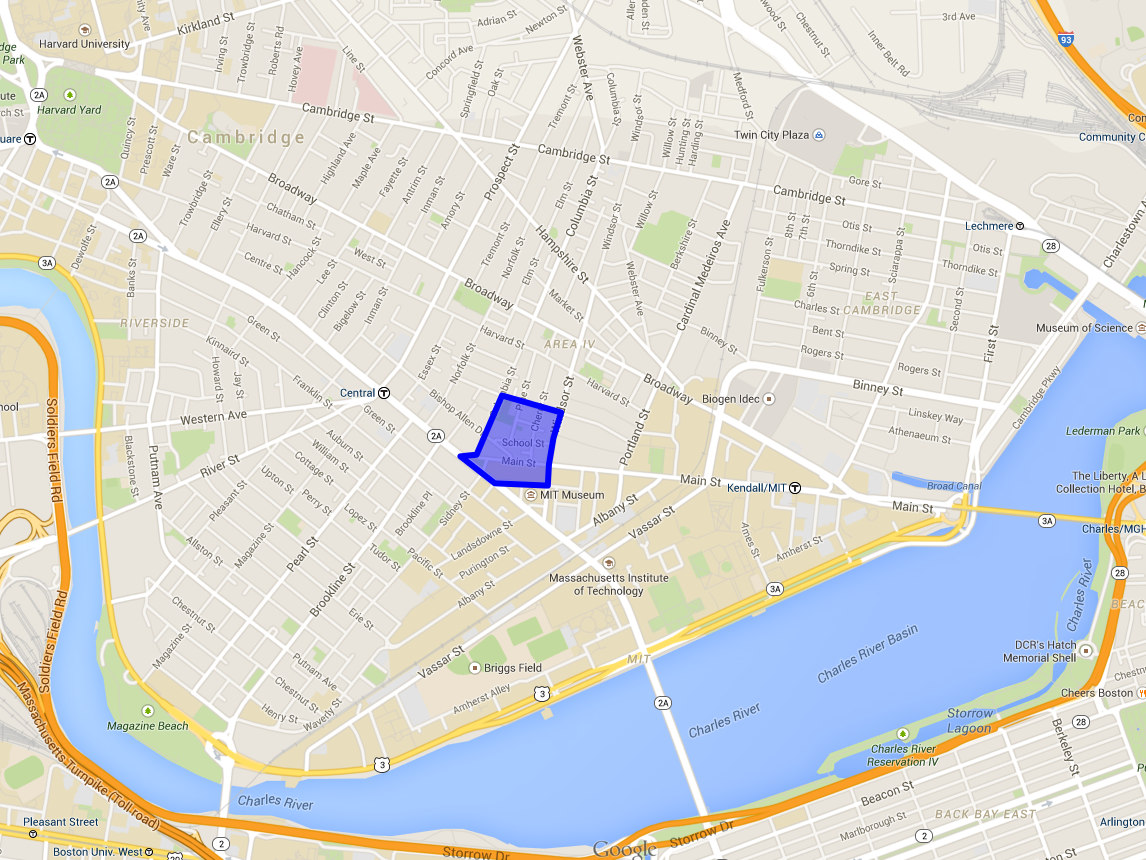

The story of my site begins long before human development of the area. As seen in the comparison of Figures 1 and 2, the natural landscape has changed quite dramatically between 1700, when the first map was created, and the present.

Figure 1: The site boundary and surroundings circa 1700 — (Hastings 1919)

Figure 1: The site boundary and surroundings circa 1700 — (Hastings 1919)

Figure 2: The site boundary and surroundings in 2015 — (Google Maps 2015)

Figure 2: The site boundary and surroundings in 2015 — (Google Maps 2015)

Closer examination of Figure 1 reveals that the site is located on a roadway, near a body of land known as Pelham’s Island. Additionally, an area known as the Great Marsh extends around the site on all sides.

These observations lead to an interesting analysis of how the site’s development was shaped by natural processes. Most obvious is that the existence of this island in the middle of the marsh provided good land for people to settle. It is reasonable to assume that people would not want to settle and build homes in the marsh, and so the natural landscape encouraged development in this specific location.

As people settled on this land, it became necessary to provide for transport, and so, one can assume that the natural landscape also had a hand in determining the location of the “Highway to Pelham’s Island”, known today as Massachusetts Avenue.

The intersection of Massachusetts Avenue and Main Street is one of the most interesting aspects of the site. This location contains a break in the grid of roads, and the irregularity of this junction heavily influenced my selection of the site. At first, I thought the break was determined solely by the need to connect two major roads. However, now I can see that the natural feature of Pelham’s Island was a major factor in determining just where the roads would be placed, and where they should start and end.

Present

Similar to how major through ways such as Massachusetts Avenue and Main Street continue to have lasting influence and character in the city, the same natural processes that shaped the early development of this location continue to craft its present situation. In the case of the early historical influence, nature often had a dominating role in the give and take between development and the natural world. There wasn’t much one could do about the large waters or marshy grounds that filled much of present day Boston and Cambridge. Likewise, many urban elements today are at the mercy of the force of nature.

Take the intersection in Figure 3 for example. Massive road construction and patching was undertaken because of the degradation in the pavement. Next, one must ask what the source of the damage is. Based on the linearity in the patch, and the alignment with the road, I would guess that there is a pipe carrying water running underneath the road. A small leak resulted in water seeping under the road, and with the extreme cold experienced during the winter, the water froze, expanded, and damaged the surface pavement. This problem will persist of course, as leaks are inevitable and the climate of this area will soon bring freezing temperatures again.

Figure 3: Damaged pavement at the intersection of Main St. and Windsor St. Notice the length andlinearity of the break. — Photo by author

Figure 4: A crack in a concrete beam in a building on Windsor St. Notice the two layers of patching. — Photo by author

Other natural forces are at work under the ground. The land itself is shifting and the cracking in the beam of the building in Figure 4 is evidence of this. It seems as though after the building was constructed, the soil “settled” and created an uneven loading situation. This resulted in an unusually large amount of stress on the concrete, and the cracking seen in the image occurred. This cracking compounds with the freezing of water that works to further the damage, just as the water resulted in the damage to the pavement mentioned before. In this way, the crack and damage to the beam is not the product of overburden from within the building, but rather the natural processes working beneath the surface.

This kind of damage is of special importance because this section of the site seems to extend past the edge of Pelham’s Island. That means that this building is constructed on filled land. In her book, The Granite Garden, Anne Spirn notes that filled land is often “loose” and unstable relative to more permanent pieces of land (Spirn 1984, pg. 19). The loose soil make for land that is more susceptible to settling and the damage seen here.

Loose soil and fill is of particular interest in the Boston area, and in the northern half of this site as well, because of the lack of public knowledge of the fill. In The Granite Garden, Spirn emphasizes that in areas typically thought to be without seismic threat are of particular danger since this risk is largely unrecognized by the residents (Spirn 1984, pg. 93). While in the book, she is referring specifically to earthquakes, this issue can trickle down to such a level that the unrecognized instability in filled land could lead to problems for urban development.

The evidence of natural processes is not limited to those effects seen beneath the ground. Examine the damage done to the brickwork in Figure 5. The eating away of the mortar between these bricks is quite pronounced. Weathering and erosion is a commonly known force of nature and this combination of wind, water, and temperature fluctuations has taken quite a toll on the foundation of this building as the sediment holding the bricks together becomes worn and is carried away.

Figure 5: Damaged brickwork on Columbia St. — Photo by author

Figure 6: A bent telephone pole on State St. Notice the discoloration of the pole near the bend. — Photo by author

Another example of a natural process leaving its mark on the urban landscape is seen in the deformation of the telephone pole in Figure 6. In this image, it is clear that the pole has deformed under the load of the wires and is no longer straight, but rather noticeably bent. It is easy to imagine that this is not the intent of the engineer who designed the telephone pole, but rather the hand of nature having its way. Since the pole is wooden, I would conclude that this extreme deformation is a result of the high levels of moisture in the air coupled with the cold temperatures. Similar to the story behind the broken pavement, I suspect the moisture and cold weakened the material properties of the pole and allowed the unequal tensions in the wires to deform the pole beyond its elastic limits.

Wires in the sky are also at war with the vegetation as seen in Figure 7 where a tree branch is on track to bring down a power line. This situation is common all along this road as many street trees come in conflict with this line that runs along the Colombia St. This tree is unique however in that is has yet to be pruned back. The trees have shaped the success of the lines by requiring additional work to manage and prune near the power lines. Thinking further, a strong gust, or a particularly heavy snowfall may be all that is needed for the tree to have a much more dramatic influence on the residents of this neighborhood.

Figure 7: A tree branch resting on a power line on Columbia St. The angle formed in the wire indicates that the branch is indeed physically touching the wire.— Photo by author

Figure 8: An empty lot surrounded on all sides by taller buildings. Notice the massive amounts of snow piled within the fence as well as the “roughness” of the solar panels on the building to the left, and the sharp angles of the church to the right.— Photo by author

The wind cannot be ignored. Whether it be eroding away brick, blowing down a tree branch, or in the case of Figure 8, dumping massive amounts of snow on the ground, the wind is a force to be reckoned with. In this situation, there is an empty lot surrounded on all sides by tall, “rough” buildings. By being lower than the surrounding buildings, this lot creates a zone of low pressure when the wind blows over the taller structures. This creates a trap for snow-laiden air to fall. Compounding the height differential is the turbulence created by the “roughness” of the surrounding buildings. In The Granite Garden, Spirn discusses this phenomena in reference to gusts and lulls (Spirn 1984, pg. 51). On the scale of cities, the rugged edges and variations in height create frictional drag that slows down the wind—precisely what is occurring on a very small scale in this example. Turbulence in the air creates a situation more suitable for the snow to be taken out of the streamline and fall into the lot. In this way, the natural process of wind combines with some precipitation to render this lot effectively useless.

Figure 9: A contextual photo of the tree and fence. — Photo by author

Figure 10: A close-up photo of the fence entering the tree. — Photo by author

Perhaps the most striking example of natural processes taking over the urban landscape can be seen in Figures 9 and 10. In this setting, one finds a tree and a fence, but strikingly, the fence goes into the tree! One can easily guess that this is the product of the tree growing and expanding around the fence, but this is not to be taken lightly. As shown in the figures, the tree has firmly claimed its location and has made a joke of the man-made fence.

This example speaks to a larger, perhaps metaphorical, theme within the interactions of the urban and natural worlds. This fence divides two residences along a property line, and the tree began its life fully within the one property. Yet, as is a commonly seen throughout the aforementioned examples, the natural world quite literally knows no bounds in its persistence through the ages.

Future

That is not to say that coexistence is impossible. With sound planning and respect, the interactions between the urban landscape and natural processes can create a harmonious symbiosis. Pictured in Figure 11 is an example of what is possible when urban design leverages the processes of nature.

Figure 11: The Anthony Paolillo Tot Lot as seen from the street. — Photo by author

Figure 12: A tree strains to reach the sunlight on Cherry St. — Photo by author

Here one can see the Anthony Paolillo Tot Lot, a small park designed for young children and completed in 2010 (Cambridge Community Development Department 2011). The eye immediately goes to the trees, which are able to reach up to the sunlight that comes in clearly over the house of only two stories. The product of the abundance of sunlight can be seen in the density of twigs on the trees. During the summer, these trees will be thick with leaves offering cool shade to the children playing below. A small breeze will cool things further, but due to the close proximity of houses, there is protection from gusting winds.

Contrary to the gusty and harshly lit tennis courts in the park across the street, the Tot Lot creates a pleasing micro-climate and ambiance that is perceptible even in the dead of winter. The shade and natural materials counter the “urban heat island” effect described in The Granite Garden where man-made materials absorb and hold heat, raising the temperature of the immediate area. Spirn notes that “landscaped parks”, like the Tot Lot, create relatively cool spots in the urban form (Spirn 1984, pg. 54).

Furthermore, the trees seem to be healthy. Nature appears quite satisfied with the small park. Notice the stark difference in the angle at which the trees grow in Figures 11 and 12. In Figure 12, the tree must strain itself to reach out from the shadow of the building and capture sunlight. However, in the Tot Lot, the trees are easily able to get morning and evening sun due to the lack of buildings to the east and west, and the low houses to the south. It is not just the urban environment that benefits from the Tot Lot’s careful construction, but the natural world as well.

This ideal example of the urban landscape existing within the bounds of natural processes is a beautiful thing. Rather than butting heads and constantly patching roads, trimming trees, and sealing bricks, this location is designed in light of, rather than in spite of, these natural processes.

Conclusion

Through the examination of natural processes on the site through time, it is indisputable that the urban landscape cannot exist without nature’s mark. From shaping the early years and settlement, to testing the success of the current urban landscape, the natural world responds to urban design and speaks for the future. The plea of the cracks, the bumps, and the bends is to design with, and not against these processes.

1.

Cambridge Community Development Department (2011). Clement Morgan and Pine Street Parks. Retrieved from http://www.cambridgema.gov/CDD/Projects/Parks/clemmorganpark.aspx on March 5, 2015.

2.

Google Maps (2015). Cambridge, MA. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/maps/@42.3590097,-71.0894877,15z on March 4, 2015.

3.

Hastings, L. (1919). Cambridge Highways. Harvard University Library Archive.

4.

Spirn, A. W. (1984). The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. Basic Books.