Located adjacent to the intersection of Massachusetts Avenue and Main Street, it is unsurprising that the story of my site heavily intertwines with the transportation developments in this area. Much like the rumblings from the Red Line below, the role of transportation is more than skin deep. Through my observations, it is clear that accessibility to my location has permeated all facets of its development, and has been the single most-important factor in shaping the development of my site.

Transportation as a Lens

While certainly not the only force at work shaping the development of the site, transportation provides a useful context from which to consider social, economic, and political trends relevant to this site. By framing the history of the site in terms of the transportation developments relevant to its upbringing, one can focus on the changing face of the site and the socio-economic ramifications of these changes.

Transportation developments will serve as a guide from the initial natural state, through the construction of roads and bridges, and into the rise of the automobile and public transit. Transportation shapes accessibility, and accessibility shapes the social, political, and economic development of a location. This back and forth creates a interesting framework that is useful in understanding how a location has changed over time.

First, it is useful to trace the trends through time, starting with the initial settlement of the site. Then, further analysis and context will reveal interesting trends. These trends are supported by broad themes that describe change not just for this site, but for urban development at large.

Troublesome Terrain

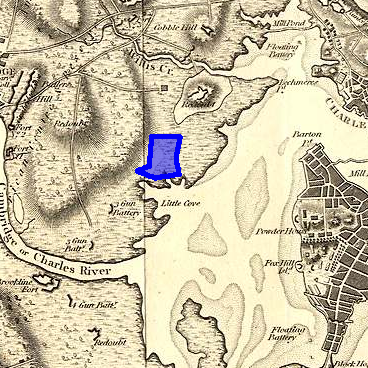

During the early years of settlement in the Boston area, the site remained largely undeveloped. As seen in Figure 1, in 1777, a single road connected the site to Harvard Square in Cambridge, though that journey was quite distant on foot. To the south-east, the site bordered the Charles River, preventing direct access to the city proper of Boston. When combined with the additional geographic challenge of the surrounding marshland, this location was not at all conveniently accessible. I suspect that the impracticality of traveling to and from this location stunted its growth in the early years.

Figure 1: The site boundary and surroundings circa 1700 — (Hastings 1919)

Figure 1: The site boundary and surroundings circa 1700 — (Hastings 1919)

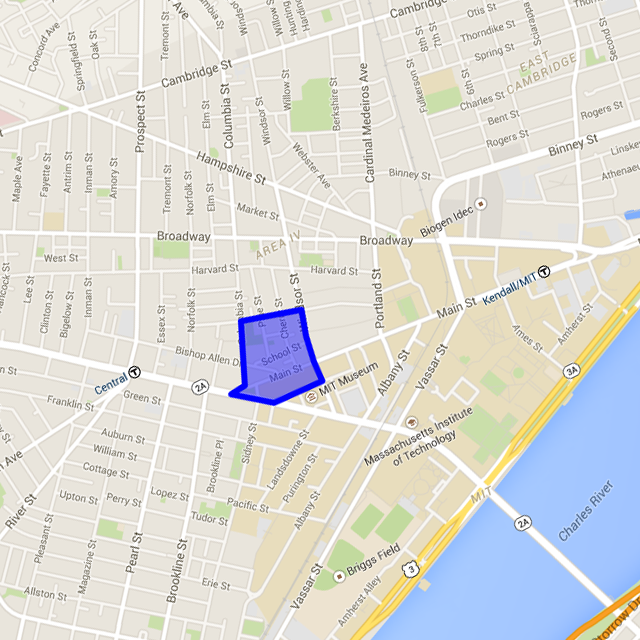

Figure 2: The site boundary and surroundings in 2015 — (Google Maps 2015)

Figure 2: The site boundary and surroundings in 2015 — (Google Maps 2015)

Furthermore, the population of Boston was not at all pushing land resources at this point in history to require the rather distant land to be developed; the total population for Boston still fell shy of 25,000 people (Spirn 2015).

The Great Road

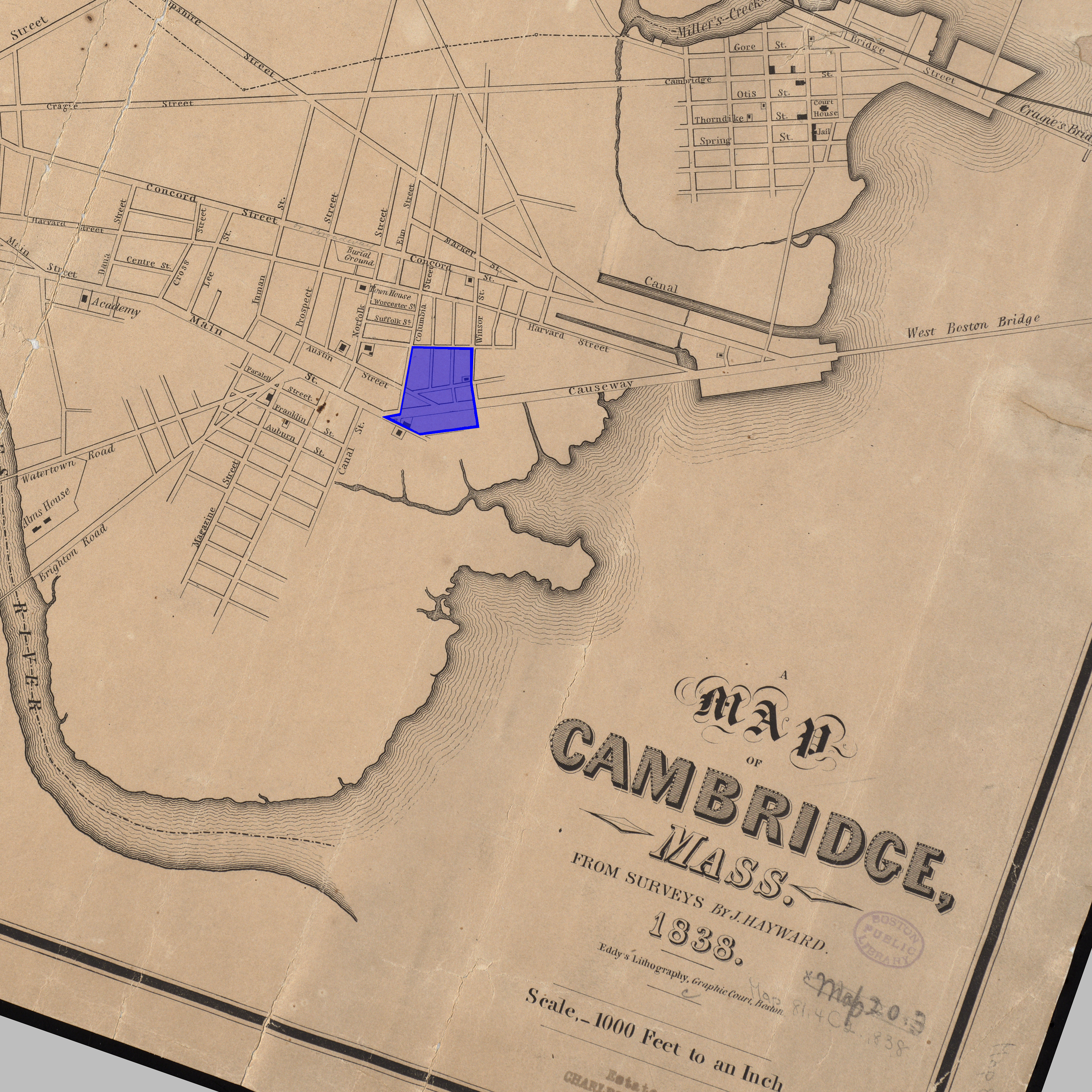

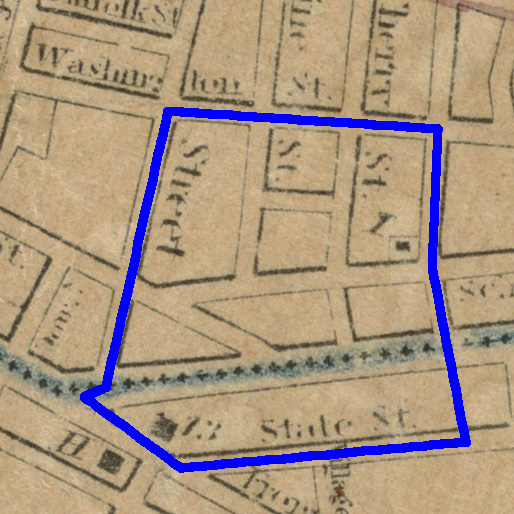

The first major step towards improving accessibility to the site came in the year 1793 with the construction of the West Boston Bridge (Spirn 2015). This bridge nearly directly linked the site to the center of Boston. The previously named “Highway to Pelham’s Island” became Main Street, and houses and churches sprung up. This is evidenced by the dramatic change in the number of roads and buildings as seen in the comparison of Figures 3 and 4. Though more detailed map data was unavailable for this time period, the construction of this location is documented in Lucius Paige’s book, History of Cambridge. He writes that “after the opening of the great road”, many houses, stores, and sheds were erected, even within the same year (Paige 1877).

Figure 3: The site circa 1800. Notice the lack of any development within the site’s boundary. — (Marshall 1806)

Figure 3: The site circa 1800. Notice the lack of any development within the site’s boundary. — (Marshall 1806)

Figure 4: The site in 1838. In just a few years, the West Boston Bridge has brought life to this location. — (Hayward 1838)

Figure 4: The site in 1838. In just a few years, the West Boston Bridge has brought life to this location. — (Hayward 1838)

An additional factor in the sudden boom in this area comes from its location between the relatively populous hubs of Boston and Harvard. Returning to the idea of accessibility and transportation, the geography provides a prime location for store owners to set up shop and provide services to people journeying from one center to the other. I would hypothesize that this aided in the macro-level development of the greater Central Square-Kendall Square area. Furthermore, on the site, one notices a large concentration of commercial land-use along Main Street (see Figure 7) which is supportive of this theory.

Railroads

Not long after the construction of the West Boston Bridge came a rail line. As seen in Figure 5, a transport line can be seen following the same path as Main Street. Upon inspection of the larger map, one can see this is a horse railroad line connecting Harvard Square with Boston by way of the West Boston Bridge. This transport connection increased accessibility of the site. I suspect that this, in turn, contributed to the steady development of this site as buildings continue to be erected and density increased.

Figure 5: Notice the rail car line running down Main Street. The access to transportation will shape the site dramatically. — (Mason 1861)

Figure 5: Notice the rail car line running down Main Street. The access to transportation will shape the site dramatically. — (Mason 1861)

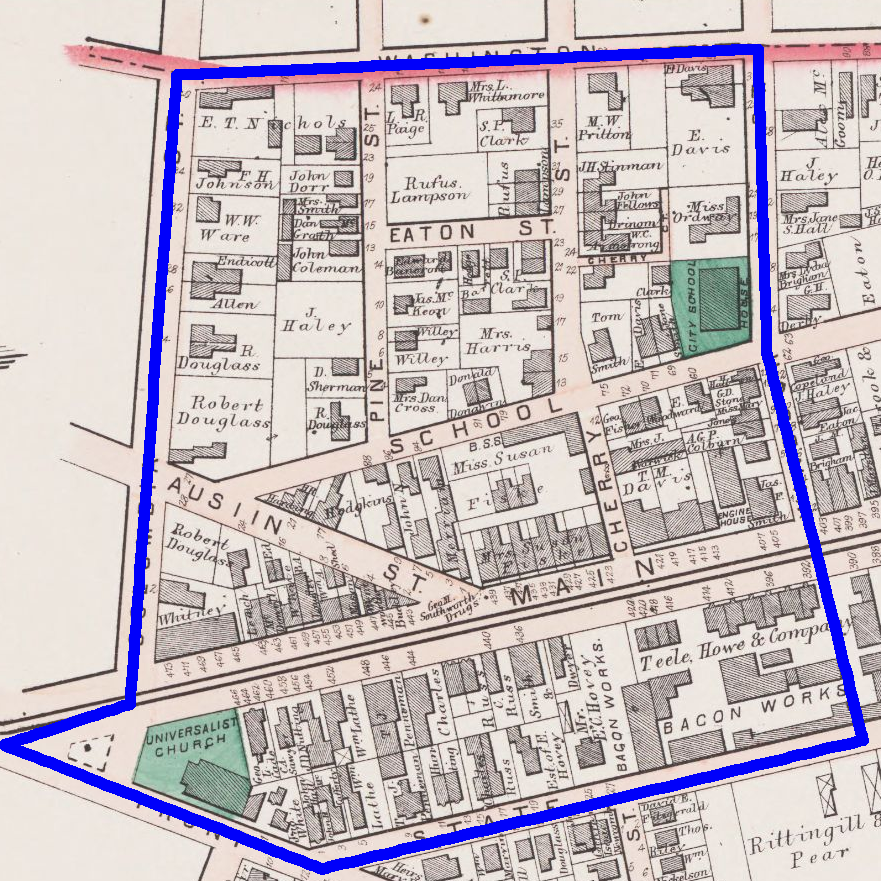

Figure 6: Notice the density of the buildings. The site has seen steady development since the initial settlement. — (Hopkins 1873)

Figure 6: Notice the density of the buildings. The site has seen steady development since the initial settlement. — (Hopkins 1873)

Additionally the railway may have enabled the development of the site’s first manufacturing facilities. As seen in Figure 6, plots south of Main Street have been developed in to food processing plants. These plants may have depended on the railway for the transportation of the raw materials and finished goods.

The Auto

Not long after the turn of the century, the automobile found its way into the lives of the general public, heralding in a new period of transportation and access. The automobile influenced both the physical identity of the site, and the way in which culture was able to exist.

In a physical sense, the automobile necessitated the conversion of stables to garages and parking spaces, as well as the creation of filling stations. This transition can be seen particularly well in the comparison of Figures 7 and 8 as three large, public garages and a filling station come to the site.

Figure 7: Notice the stables, the grey buildings. These will soon be replaced with the coming of the automobile. Colors are LBCS Standard.— (Sanborn 1900)

Figure 7: Notice the stables, the grey buildings. These will soon be replaced with the coming of the automobile. Colors are LBCS Standard.— (Sanborn 1900)

Figure 8: Notice the change in the transportation land use in grey. With the rise of the automobile comes three huge garages and a filling station. Colors are LBCS Standard.— (Sanborn 1934)

Figure 8: Notice the change in the transportation land use in grey. With the rise of the automobile comes three huge garages and a filling station. Colors are LBCS Standard.— (Sanborn 1934)

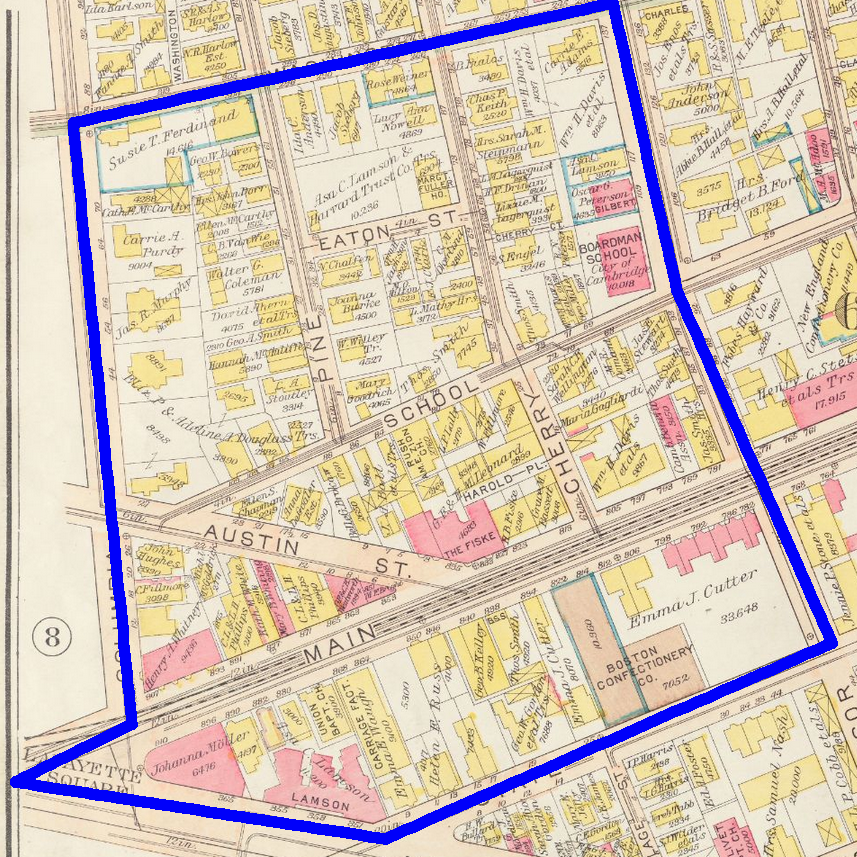

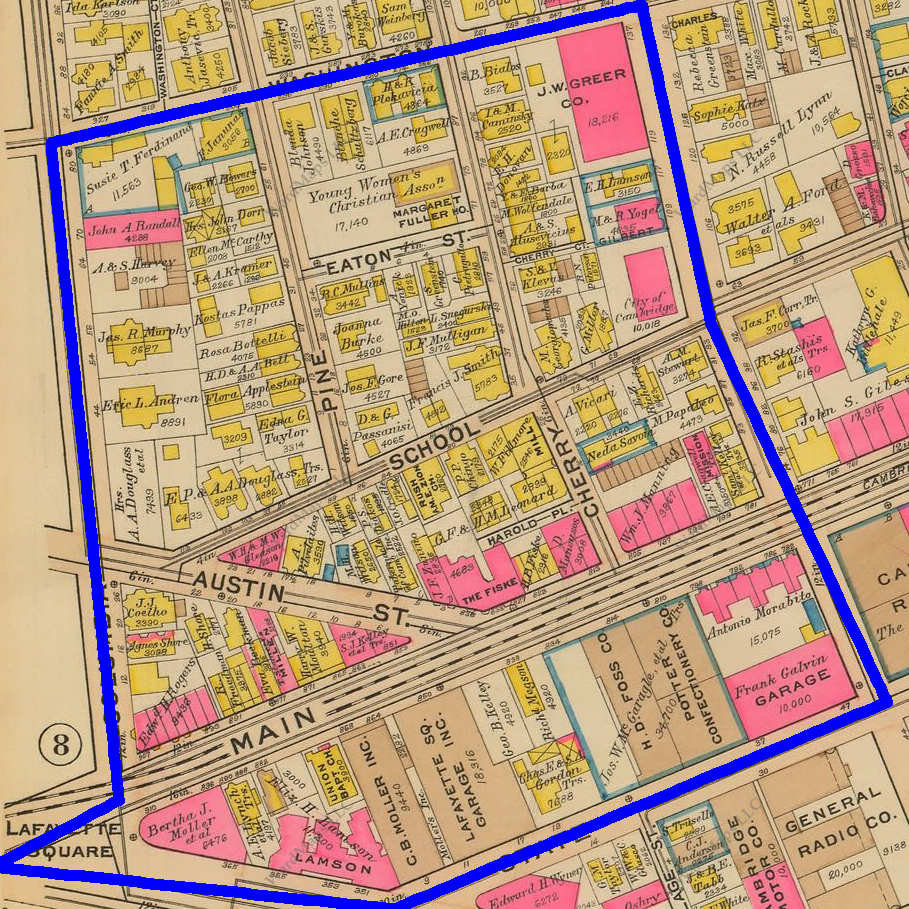

Furthermore, Ken Jackson in his book, The Crabgrass Frontier, comments on a finer detail to the introduction of the automobile. He notes the importance that with the automobile came the truck, which “could do four times the work of a horse-drawn wagon” (Jackson 1985, pg. 183). The increased construction power may have contributed to a decrease in the cost of construction which could have contributed to the increase in the number of stone buildings on the site between 1916 and 1930 (Figures 9 and 10). An alternative hypothesis for the source of this observation is simply the economic prosperity that was being experienced during the time immediately preceding the crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression.

Figure 9: The site in 1916 — (Bromley 1916)

Figure 9: The site in 1916 — (Bromley 1916)

Figure 10: Notice the larger number of stone buildings (those shaded in brown) when compared to the 1916 map. — (Bromley 1930)

Figure 10: Notice the larger number of stone buildings (those shaded in brown) when compared to the 1916 map. — (Bromley 1930)

The automobile also provided the possibility for change in that it expanded the land that could be considered appropriate to inhabit and still work in the city. Public garages provided storage for automobiles during the work day and so, those fortunate enough to own cars and also afford to pay for day storage could move further away from the city itself, but still commute in for work and play. While I expected this cultural shift to show itself in the immediate thinning out of the site, the desire for housing in this neighborhood did not decline until much later.

I suspect that this is a result of the high cost of parking within the city. Since the public transportation was still rather slow, one would have to drive nearly all the way into the city, and I would guess that the burried parking garages of today did not yet exist.

Red-lined

The final significant development in transportation is the introduction of the Red Line and the expansion of the Boston subway at large. In his book, Jackson comments that “the electric streetcar represented a revolutionary advance in transportation technology” in that it was many times faster than the previous public transportation lines (Jackson 1985, pg. 115). This added speed encouraged the public use of these streetcars and granted access to goods and services to a much larger population.

Unfortunately, this access did not favor the site at the corner of Main Street and Massachusetts Avenue. The Red Line stops in Central Square and Kendall Square. The location of interest falls between these two locations and so, it is not a stretch to infer that the subway did not bring many new customers to the location or offer residents more convenient access to the city. By examining the maps from 1934 and 1950 (Figures 11 and 12), one sees very little change between these two dates. This is not to say that there is no effect, but rather the repercussions of the Red Line station locations took longer to surface as the many commercial businesses slowly withered and closed shop by 1970 (Figure 13) while perhaps business in Central Square and Kendall continued to grow.

Figure 11: The site in 1934. Colors are LBCS Standard. — (Sanborn 1934)

Figure 11: The site in 1934. Colors are LBCS Standard. — (Sanborn 1934)

Figure 12: Between this 1934 map and the 1950 map, not we do not see the dramatic change seen during other time periods. Sure, some businesses change, but close inspection reveals that the changes are only slight. For example, a tin shop takes the place of a woodworking shop. Colors are LBCS Standard. — (Sanborn 1950)

Figure 12: Between this 1934 map and the 1950 map, not we do not see the dramatic change seen during other time periods. Sure, some businesses change, but close inspection reveals that the changes are only slight. For example, a tin shop takes the place of a woodworking shop. Colors are LBCS Standard. — (Sanborn 1950)

Figure 13: Between the years of 1950 and 1970, the site changes quite significantly. There are fewer houses, more parking lots, and more open space. The site is clearly in decline. Colors are LBCS Standard. — (Sanborn 1970)

Figure 13: Between the years of 1950 and 1970, the site changes quite significantly. There are fewer houses, more parking lots, and more open space. The site is clearly in decline. Colors are LBCS Standard. — (Sanborn 1970)

In addition to access within the city, subway and commuter rail expansions contributed to the continued suburbanization of the site. Jackson writes that electric streetcars allowed for public transit lines to “encompass an area triple the territory of the older walking city” (Jackson 1985, pg. 115). Whereas initially there was some attraction to this site due to its location on the outskirts of both Boston and Harvard, the suburbs further outside of the city were becoming more accessible given the development and expansion of the public transportation system. In turn, these locations became more attractive to residents and as a result, there is a thinning out of the site during the period of 1950-1970. This change can be seen in the comparison of Figures 12 and 13.

Ramifications and Broader Themes of Suburbanization

In stark contrast to European culture, Ken Jackson comments on the curious case of American suburbanization. Jackson notes that whereas in many European cities, the wealthy will continue to move inwards and push the poorer classes to the outskirts of town, wealthier Americans typically choose to move outwards to the suburbs and leave the lower classes to the inner city (Jackson 1985).

This trend provides a rise and fall of the site in question as the city first grows to establish the suburb of Cambridgeport and then consumes the location into an urban zone. Initially, the site’s location provided an escape from the city and was, in essence, a suburb. A resident could still work in the city, but in the evenings, could easily retire back to his or her residence. This gave rise to a relatively wealthy, largely residential area. As Boston and Cambridge continued to grow however, the neighborhood became less of a peaceful retreat and the wealthy once again took off and left for the country.

Of course, the transportation developments previously discussed play major roles in the broad trend of suburbanization. By establishing the location as a suburb in the first place, improving access with the rise of the rail car, and finally providing fast, long-distance commuting power with the automobile and commuter rail lines, transportation developments fueled suburbanization. Now, one can dive deeper to uncover the social and economic ramifications of how the site developed.

Social

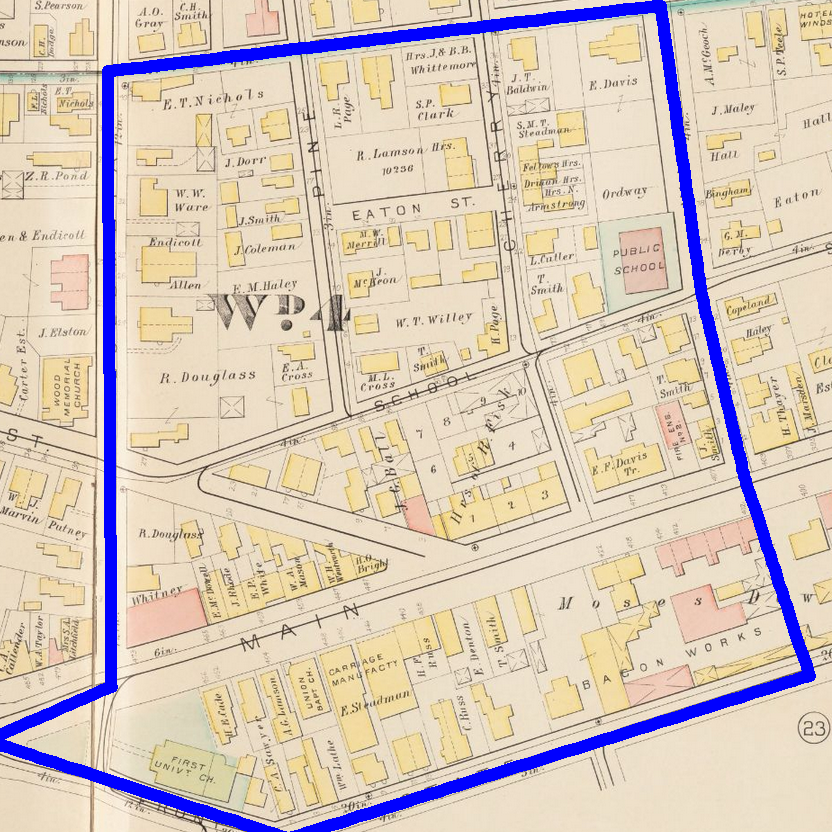

Near the initial settlement of the site, one would expect a wealthier population founding a largely residential zone. Upon inspection of Figures 14 and 15, it seems as though not only were the residences large, single-family homes on large properties, but the property owners were mostly white. Stereotypically, these people fit the definition for the wealthier class that Jackson would expect to settle this land.

Figure 14: Notice the large houses and significant plots of land in the site. This suggests wealthy landowners. — (Franklin View Co. 1877)

Figure 14: Notice the large houses and significant plots of land in the site. This suggests wealthy landowners. — (Franklin View Co. 1877)

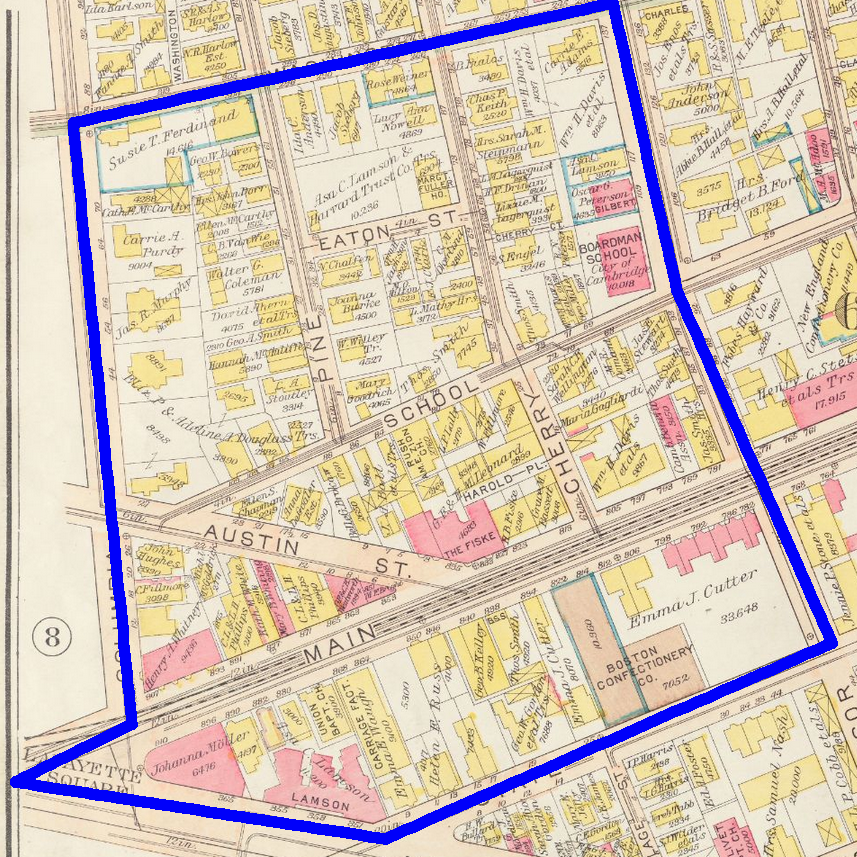

Figure 15: Notice the names of the property owners. Douglass, Davis, Smith, Clark, etc. would suggest white landowners. — (Hopkins 1886)

Figure 15: Notice the names of the property owners. Douglass, Davis, Smith, Clark, etc. would suggest white landowners. — (Hopkins 1886)

As time passes and the city grows up around this area, the location is less desirable and should hardly be considered a suburb anymore. A trend away from single family homes and towards multi-family homes or flats also develops. This is indicative of a less-wealthy population moving into the area.

Further support for this trend is found in the Margaret Fuller Neighborhood House. In 1902, this house was converted into a “Settlement House” that helped immigrants assimilate into American culture (House 2013). Moreover, in 1937, Cambridge’s first public housing project was completed in a lot adjacent to the site (Spirn 2015). While there is not an overwhelming amount of evidence to support the initial settlement of the wealthy class due to lack of historical documentation, there is strong evidence to support the eventual dominance by a lower class population. In this way, the development of the site through a variety of factors such as transportation and accessibility has shaped the social makeup of the site.

EconomicThe site has also been shaped by transportation and the rise and fall of the suburb economically. Not much information exists about the economic entities in the initial settlement of the location, but it is clear that commercial businesses flocked to grab street front on Main Street, and industry was keen to move in, especially given the access to the rail line. The “bacon works” established itself as early as 1873, and interestingly, food processing continues in that location even today with Cambridge Brands, a candy company. I suspect that we see this relationship through time because of the relatedness in the building needs and in acquiring raw materials. On one hand, it may be very expensive to build a factory and it is much more cost effective to simply move into an old food processing factory. Alternatively, as is more interesting with Cambridge Brands, the possibility of sharing resources may provide incentive for neighboring plants. For example, in Figure 16 we see two candy companies in the same vicinity. It could be possible that it is advantageous for these two companies to be located together if, for example, they both sourced their sugar from a nearby sugar mill.

Figure 16: Notice the two locations highlighted in blue, one within the site and one outside. Both buildings house candy manufacturing operations. — (Bromley 1916)

Figure 16: Notice the two locations highlighted in blue, one within the site and one outside. Both buildings house candy manufacturing operations. — (Bromley 1916)

As time passes, the overall economic activity of this region declines as many shops close and are converted to parking spaces. This trend lies at the intersection of map observations, transportation changes with the advent of the subway, and thematic trends of suburbanization.

Causation is always difficult to pinpoint, but through the broad lens of transportation, we are able to step through history and observe trends in the site. We see how transportation developments, and the changes that surround them, have a profound impact on the development of a location. These observations are validated by historical map evidence as well as larger themes of development as articulated by Ken Jackson in his book, The Crabgrass Frontier. While this site is particularly closely tied to transport, accessibility as a characteristic of any physical place has an immense role in shaping its future. This conclusion begs for validation from other sites and cities and questions the future of accessibility and the role it will play in shaping the urban landscape.

Bromley, G. (1916). Atlas of the city of Cambridge. Harvard University Library Archive.

Bromley, G. (1930). Atlas of the city of Cambridge. Ward Maps LLC.

Franklin View Co. (1877). City of Cambridge, Mass. Boston Public Library.

Google Maps (2015). Cambridge, MA. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/maps/@42.3590097,-71.0894877,15z on March 4, 2015.

Hastings, L. (1919). Cambridge Highways. Harvard University Library Archive.

Hayward, J. (1838). Map of Cambridge, Mass. Boston Public Library.

Hopkins, G. (1873). Atlas of the city of Cambridge, Massachusetts. Harvard University Library Archive.

Hopkins, G. (1886). Atlas of the city of Cambridge, Massachusetts. Harvard University Library Archive.

House, M. F. N. (2013). Margaret Fuller Neighborhood House. Retrieved from http://www.margaretfullerhouse.org/who-we-are/about-us/ on April 7, 2015.

Jackson, K. (1985). The Crabgrass Frontier . Oxford University Press.

Marshall (1806). Boston and its Environs circa 1800 . Retrieved from http://www.earlyamerica.com/earlyamerica/maps/bostonmap/enlargement.html on April 7, 2015.

Mason, W. (1861). Map of Cambridge, Mass. Boston Public Library.

Paige, L. R. (1877). History of Cambridge, 1630-1877 . H. O. Houghton.

Sanborn, M. (1900). Insurance Maps of Cambridge, Massachusetts. ProQuest LLC.

Sanborn, M. (1934). Insurance Maps of Cambridge, Massachusetts. ProQuest LLC.

Sanborn, M. (1950). Insurance Maps of Cambridge, Massachusetts. MIT Libraries.

Sanborn, M. (1970). Insurance Maps of Cambridge, Massachusetts. MIT Libraries.

Spirn, A. W. (2015). Timeline. Retrieved from

http://architecture.mit.edu/class/city/timeline.html on April 7, 2015.