Figure 1: Rendering of Central square for a 2013 zoning proposal shows green trees on a beautiful sunny day.

Figure 1: Rendering of Central square for a 2013 zoning proposal shows green trees on a beautiful sunny day.Cities are designed for the beautiful days. Designers will plant trees and place benches underneath to be enjoyed in dappled sunlight on a warm summer day. Humans tend to construct the places they desire to fit with the climate they prefer, but what if the weather is not pleasant? What if it is winter time and the trees are not in bloom? You never see architectural rendering for parks or public spaces set in the snow, but in Massachusetts there is snow on the ground for at least at least three months out of the year. White winter landscapes can be a beautiful site and provide ample opportunity for outdoor recreation, but they can also greatly daily disrupt urban life. Cities must deal with the natural forces that shape our world, for better or worse, and have existed in the area for far longer than any block of concrete laid down by humans. Even in a carefully constructed urban landscape, there are still harsh, as well as subtle, natural phenomena simply beyond human control.

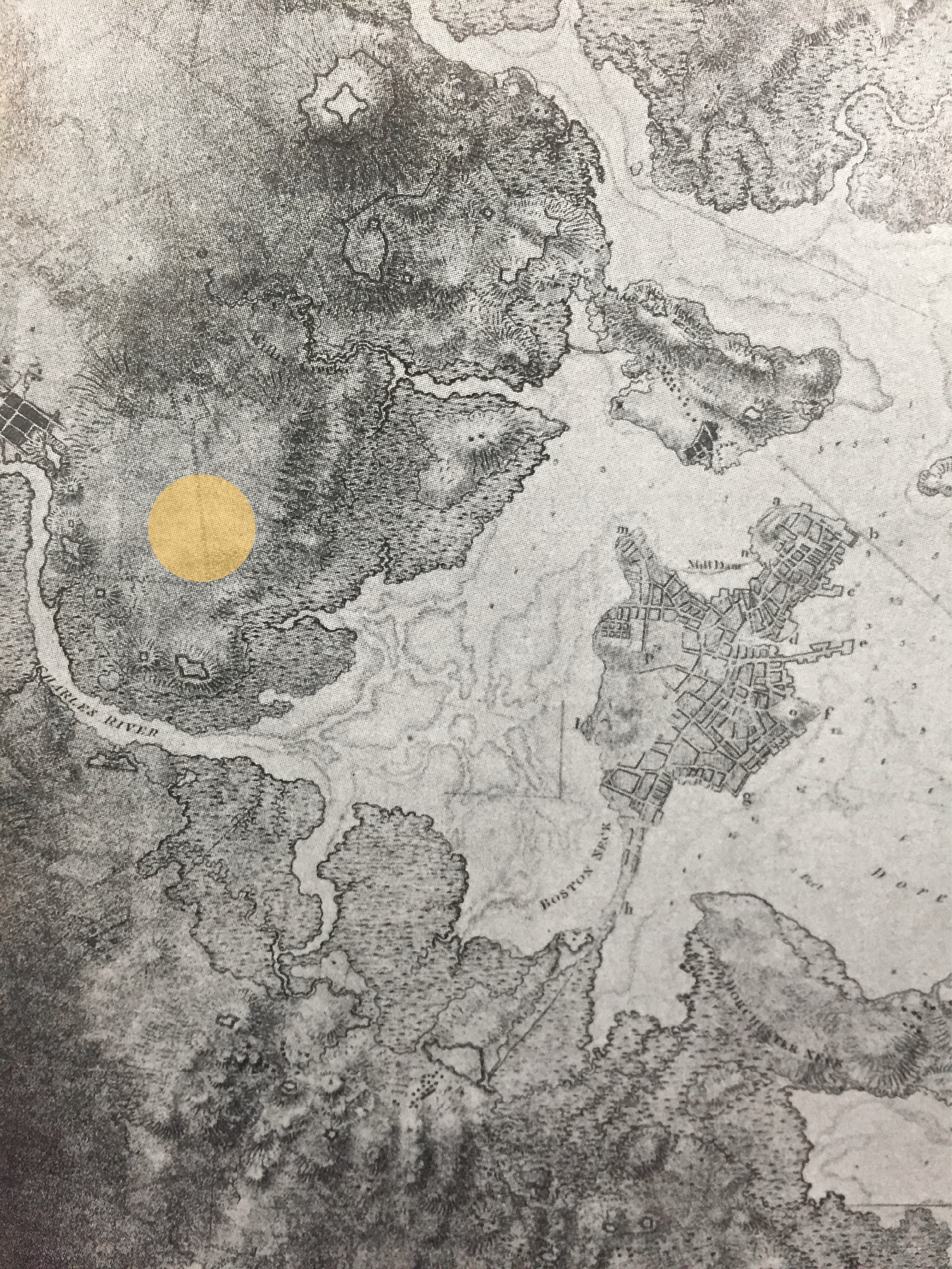

Figure 2: Map of Boston/Cambridge Area from 1781 showing topography of the region. My site would be somewhere within the yellow highlighted area. Note the hilly regions to the east and south.

Figure 2: Map of Boston/Cambridge Area from 1781 showing topography of the region. My site would be somewhere within the yellow highlighted area. Note the hilly regions to the east and south. For example, human have been living on my site around Central Square in Cambridge for about two hundred years. Within the .85 square mile zone there are nice residential streets, commercial businesses, government buildings, and even abandoned lots. There are also three major thoroughfares that pass through my site at irregular angles. However, if one takes a step back to look at the site in a broader context, it becomes apparent that, although not particularly close to the Charles River, is shaped by the bend in the river’s banks. The geometries that form three of the boundary streets of this site, Western and River Avenues, merging to form Prospect Street, Massachusetts Avenue, and Harvard Street, all come in at different seemingly odd angles, but are actually fairly perpendicular to the Charles River. They are the continuation of bridge streets crossing over to Cambridge from Boston and Brookline, showing how large-scale natural landscape can influence the development of smaller urban areas, regardless of land use.

Figure 3: Map of Cambridge Area when the city was first starting to really be developed. The groundwork for my site has already been laid and can be found in the red highlighted area. Note the stream that comes in from the western side, supplying the area with fresh water and the main roads branching out from the bottom right corner of my site, making it natural location for a city center.

Figure 3: Map of Cambridge Area when the city was first starting to really be developed. The groundwork for my site has already been laid and can be found in the red highlighted area. Note the stream that comes in from the western side, supplying the area with fresh water and the main roads branching out from the bottom right corner of my site, making it natural location for a city center. The area of my site was first settled in the early part of the 19th century, likely because it was in a desired setting, on relatively flat terrain with easy access to nearby streams and the Charles River. There were once hills to the eastern and southern sides that may have served to protect the area from winds and storms coming in from ocean, but those hills have since been fairly flattened in order to develop the land and expand the city over time, leaving the area unsheltered and exposed to the elements. The Boston area is notorious for its severe winters. The beginning of 2015 exemplified this trend with record-breaking amounts of snowfall and numerous storms that shut entire cities down. In my site there are many signs that display the tensions that exist when people attempt to conquer, or at least manage, this beautiful, powerful, and obstructive season that is winter.

Figure 4: Central Square T stop, practically buried in snow from early 2015 storms.

Figure 4: Central Square T stop, practically buried in snow from early 2015 storms. Like wind, snow falls on the city in a very different way than it is able to do in nature. Tall buildings and streets direct wind flow so that it is calmer in some area and extremely windy in others. During winter storms this leads to an uneven placement of snow where one can find heaps of snow fallen in some areas and barely any in other areas. This phenomenon of unnaturally large piles is only intensified when the snow from roads and sidewalks are cleared and pushed into even greater heaps on the side of the roads. Such piles take quite a while to melt and may stick around for much longer than their more evenly distributed, rural counterparts.

Figure 6: Inaccessible Bike racks on Western Avenue.

Figure 6: Inaccessible Bike racks on Western Avenue.  Figure 7: Snow on St Paul Street is pushed asside to leave a narrow icy pathway for pedestrians.

Figure 7: Snow on St Paul Street is pushed asside to leave a narrow icy pathway for pedestrians.  Figure 8: Snow on Austen Park completely covers sidewalks.

Figure 8: Snow on Austen Park completely covers sidewalks. These snow piles greatly affect urban life, especially transportation. Not only do storms themselves shut down roads, busses, and trains, but the cleared piles that remain stay on sidewalks, hindering pedestrian’s way. This is especially true for smaller streets, sidewalks on St Paul Street, for example, are only a narrow icy path, less than a foot wide with great snow banks on either side. And on Austen Park there are no exposed sidewalks at all and the pedestrians have to share the narrow road with the cars. On Massachusetts Avenue, a much larger and wider street, the sidewalks and roads are pretty clear with snow pushed to the side of the street, blocking bike paths, taking up parking spaces, and covering curbsides amenities such as public benches, parking meters, and bike racks. While riding a bicycle during a storm is not advisable, many people cycle as their primary mode of transportation in the winter. However this task becomes very dangerous when streets get narrower and icy and the paths disappear. This kind of prioritization on streets of cars over bikes and even pedestrians only leads to discouraging sustainable and healthy modes of transportation in the winter.

Figure 9: Evergreen tree and bush on Temple Street covered in snow. The tree is also missing branches, potentially as a result of damage from ice and snow.

Figure 9: Evergreen tree and bush on Temple Street covered in snow. The tree is also missing branches, potentially as a result of damage from ice and snow.  Figure 10: Icicles hanging off branges, possibly damaging the weak-wooded tree.

Figure 10: Icicles hanging off branges, possibly damaging the weak-wooded tree. Yet, its not only human activity that gets upset from the snow piles. Trees, especially evergreens and weak-wooded ones that are not native to the area, can get damaged by heavy accumulation of snow and ice on the branches, causing them to break. This is likely the cause of many older trees with missing branches along the residential Inman and Bigelow Streets. Shrubs are even more susceptible to damage as snow depth, especially when extra snow is piled from the streets, often exceeds the shrub’s height, like as seen on Temple Street and other residential areas[1]. And if plants are planted in raised planters, unprotected by the relative warmth the earth provides, their routes can freeze[2]. Furthermore, the snow piles sit around on the side of streets collecting dirt, garbage, and pollutants before eventually melting and draining into the Charles River, taking the collected toxins with it to pollute one of Boston/Cambridge’s most prized natural amenities.

Figure 13: A drain on Green Street that reads "DONT DUMP, Drains to Charles River"

Figure 13: A drain on Green Street that reads "DONT DUMP, Drains to Charles River"  Figure 12: Puddle of ice on sidewalk along Harvard Street.

Figure 12: Puddle of ice on sidewalk along Harvard Street. Thanks to the urban heat island effect, the downtown areas of cities tend to be significantly warmer than their suburban counterparts.[2] This does lead to faster snowmelt, but it also creates other very serious problems. As one of the first settled areas in Cambridge, the land at my site has had about two hundred years of heavy development since to compact soil and cover most exposed areas in layers of asphalt, concrete, and brick. This causes large puddles to form when snow melts as there is no uncompact soil to absorb the snow melt, and the drains are often unreachable or even frozen over. The puddles, like the one outside an apartment on Harvard Street, soon refreeze into hazardous ice on the road that is dangerous to pedestrians, bicyclists and drivers. Water that seeps into cracks, pipes, or other unstable places will expand when it freezes, causing cracks to worsen and important structures to break.

Figure 14: Parking lot on Temple Street with ice and many visible cracks. The whitish powdery tint to the asphalt is caused by leftover salt from trying to melt the ice and snow.

Figure 14: Parking lot on Temple Street with ice and many visible cracks. The whitish powdery tint to the asphalt is caused by leftover salt from trying to melt the ice and snow. In the parking lot on Temple Street, those cracks stand out even more significantly as it looks like someone has gone around and dusted the entire place with an additional white powder. As part of the process of clearing the snow, tens of millions of tons of salt is added to city streets every year in an attempt to lower the melting point of the street-clogging snow and ice. While there are public safety and mobility benefits that come with this method, there are also some significant ecological drawbacks. Ice doesn’t just disappear when the snow melts away but gets reluctantly absorbed by available outlets of the urban environment such as drains, planters, lawns, and gardens. As intended, the salt can mix with the snow and then get drained into the river causing over salinization of the Charles, which harms all types of aquatic plants and animals, disrupting the natural aquatic ecosystem. A 2009 study reported that nearly half of all urban and suburban streams in the northern part of the United States had salt pollution significantly above EPA recommendations and identified de-icing of roads as the single major culprit[3].

And still not all salt gets drained away. Another large portion gets absorbed by exposed soil where it causes chemical changes and a decrease in permeability, which causes soil to block water infiltration, reduces stability, and decreases overall fertility before potentially making its way down to contaminate ground water as well[2]. Salt in soil can cause dehydration in plants foliage or osmotic stress that harms root growth and disrupt nutrient intake. Salt can also be harmful to terrestrial wildlife, especially birds who often mistake road salt crystals for seeds. The consumption of even very small amounts of salt can result in toxicosis or death in bird populations. Damage to vegetation can harm wildlife as well by disrupting the ecosystems they depend on and destroying food resources, shelter, and nesting sites[4]. Furthermore, salt can damage human-built infrastructures by accelerating corrosion and deterioration of low lying structural materials such as concrete and metal. Cars are a huge, defining component of the modern cityscape and their undercarriages rust away at significantly higher rates, causing a slew of problems from subframe damage to hydraulic brake system leaks[5].

Figure 15: Tree roots on Inman Street are overpowering the brick and asphalt as they reach for better soil.

Figure 15: Tree roots on Inman Street are overpowering the brick and asphalt as they reach for better soil.  Figure 16: Trees leening southward, away from the wall and into the sun on Vail Court."

Figure 16: Trees leening southward, away from the wall and into the sun on Vail Court."  Figure 17: Hidden under the snow on the right side of the sidewalk on Inman Street is a patch of asphault that, based on the brick pattern, seems to have once been a patch of soil that was home to a tree or other plant.

Figure 17: Hidden under the snow on the right side of the sidewalk on Inman Street is a patch of asphault that, based on the brick pattern, seems to have once been a patch of soil that was home to a tree or other plant.  Figure 18: Frozen dirt patch on Prospect Street where a tree or bush once stood."

Figure 18: Frozen dirt patch on Prospect Street where a tree or bush once stood." Within my site, there are more trees and plants, both old and new, along in residential areas such as along Bigelow, Inman, and Harvard Streets and barely any foliage along the more industrial “back” streets like Sellars and Green Streets. Despite the challenges of existing in the urban environment, nature is remarkably resilient. Tree roots break through sidewalks to claim their desired soil, while their branches contort in odd angles in order to make the most of the sun. Yet, not all trees are able to survive in the city with the odds so stacked against them. There are places around my site where trees once stood, as apparent by empty planters or irregular brick patterns, but no longer do. Trees and other plants, especially ones not native to the northeast climate have a hard time surviving in compacted, frozen, and potentially over salinized soil. This means that many trees do not survive or are unable to reach their full potential in such a harsh and limited environment. The average lifespan of a street tree in a city is estimated to be somewhere between 7 and 28 years, only a small fraction of the expected lifespan of a tree in nature[6]. This phenomenon illustrates the unfortunate tendency of city dwellers to care more about short-term beauty and pleasure than longer-term sustainable practices when it comes to tree planting and environmental maintenance. Researchers at the University of New Hampshire suggest planting salt tolerant tree species like black and honey locust, red and white oak, and horse chestnut in areas of high salt concentration act as a barrier against salt contamination of soil and water supplies[4]. This leads to the idea of planners thinking about more than the aesthetic value or even durability of landscaping, but the larger effects of the ecosystem as well.

Figure 19: Benches on Western Avenue that are an unusable public space due to snow.

Figure 19: Benches on Western Avenue that are an unusable public space due to snow.  Figure 20: Small lot-sized park on Inman street in a residential area that has a locked gate and goes unused during the winter.

Figure 20: Small lot-sized park on Inman street in a residential area that has a locked gate and goes unused during the winter. On Inman Street and Western Avenue there are small public park spaces that have gone unused for months, not necessarily because of the cold weather, but more so because of the piles of snow that cover benches and tables render them unusable. They are not able to perform their role as a recreational gathering place, a natural oasis in the sea of concrete. However, just because it is cold outside, that doesn’t mean that people want to stay inside all day. Public spaces are valuable, even in the wintertime when activities like sledding, ice-skating, snow sculpture building are possible. Perhaps, a site like mine, which is rather flat, could have a park where excess street-cleared snow gets put in the winter in order to form a small hill that could be used for sledding and other winter-themed recreation. What if public spaces were truly designed to be used all year round? Maybe we would have more protected, indoor, or convertible public spaces. Maybe the benches could be under awning to shade in the summer and keep snow off in the winter. Maybe parking lots would be paved to hold water and prevent flooding and pooling[2].

Figure 21: A small evergreen tree in Bigelow Street is coincidentally getting thawed by a nearby vent, illustrating that the natural environment and urban devices can do more than simply coexist, but can have a genuinely beneficial relationship.

Figure 21: A small evergreen tree in Bigelow Street is coincidentally getting thawed by a nearby vent, illustrating that the natural environment and urban devices can do more than simply coexist, but can have a genuinely beneficial relationship.Just as the environmental context has shaped the city, activities that occur in cities continue to influence the natural environment around us. While the United States’ East Coast has been buried this past summer under more snow and water than we can handle, the West Coast is currently in a severe drought with snowfall rates in the mountains drastically below normal. There are many things that humans simply cannot control––the seasons, weather, platonic activity, or even the way a tree grows. But with the glaring realities of global climate change before us, it is becoming more important now than ever before that cities are able protect the natural resources we have left, design with sustainability and the urban ecosystem in mind, and adapt to work with natural processes instead of continually fighting against them.

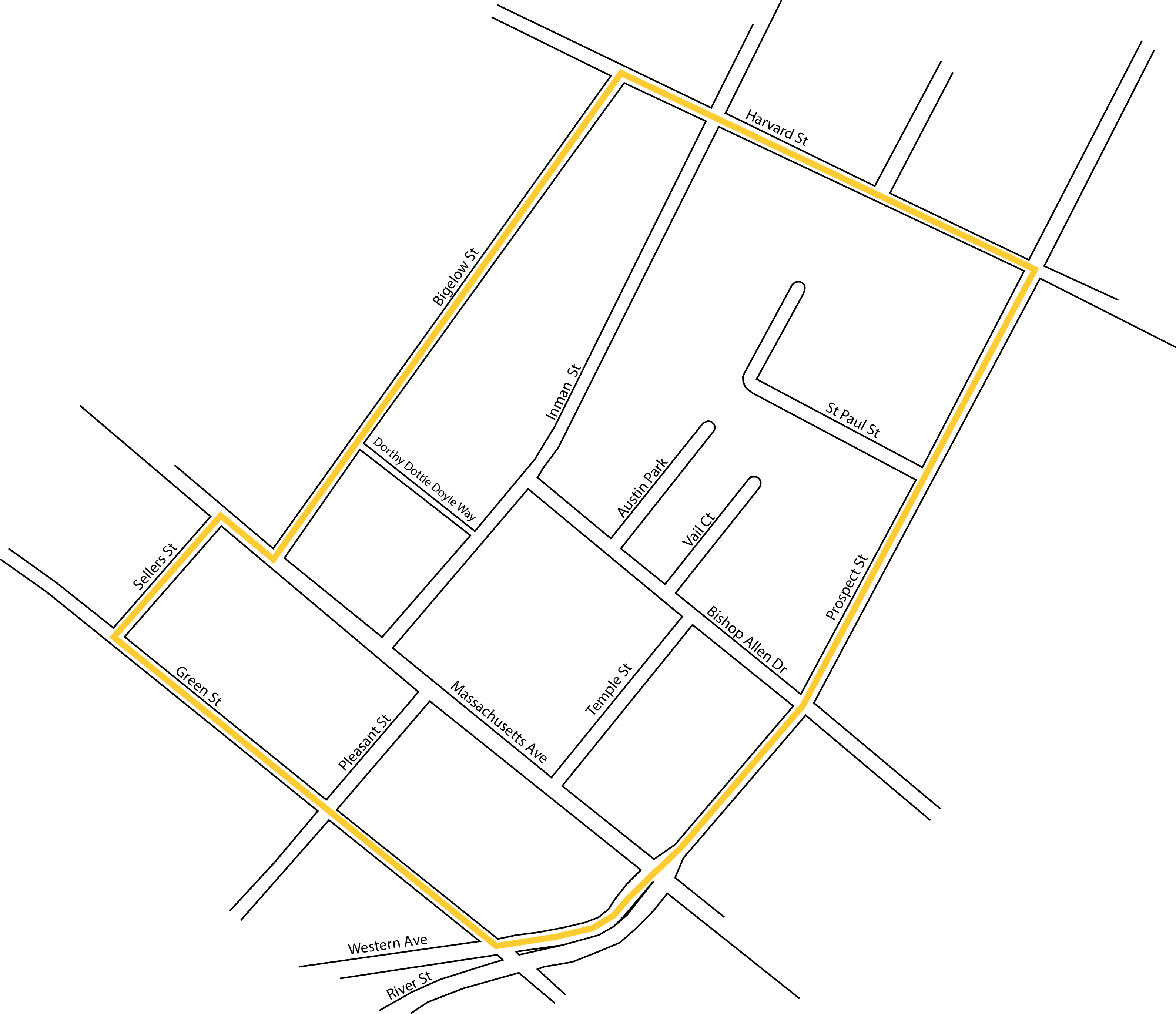

Figure 22: Map of site.

Figure 22: Map of site.Works Sited

1: "Winter Storms: Clean-up." Winter Storms. University of Georgia, 16 July 2010. Web. 2015.

2: Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic, 1984. 91, 104, 150, 191. Print.

3: Rastogi, Nina. "Does Road Salt Harm the Environment?" Slate.com. The Slate Group, 2010. Web. 2015.

4: "Environmental, Health and Economic Impacts of Road Salt." New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services, n.d. Web. 2015./p>

5: Rodman, Kristen. "Hidden Hazards of Road Salt: Car Corrosion Can Take a Toll." AccuWeather. N.p., 5 Feb. 2014. Web. 2015.

6: Roman, Lara A., and Frederick N. Scatena. "Street Tree Survival Rates: Meta-analysis of Previous Studies and Application to a Field Survey in Philadelphia, PA, USA." Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 10.4 (2011): 269-74. University of California, Berkeley and University of Pennsylvania, 2011. Web. 2015/p>

Images

Figure 1: A rendering giving a glimpse of Central Square as reimagined by consultant Goody Clancy and members of the Central Square Advisory Committee (2013).

Figure 2: Map from Mapping Boston by J.F. w> Des Barres, detiail from an untitled chart of Boston Harbor (London 1781).

Figure 3: Map of Boston Harbor, showing commissioner's lines, wharves, etc. from Mapping Boston by Ellis Sylvester Chesbrough (Boston, 1852).

Figure 4: An outbound entrance to Central Square station by Peter Enyeart (February 2015

*All images are creaded by the author unless otherwise noted.