Nature's Role in Redevelopment

I return to Dorchester Avenue, but this time I stand. I take a deep breath. I smell salt water and the exhaust of passing cars. I hear the cries of gulls that glide above Fort Point Channel. Everywhere I look, I see nature's plight. The east side of Fort Point is up-and-coming – it draws new industry, new people. But trees have a hard time growing and many roads are cracked and sunken. The west contains marginally more green space, but faces its own set of foundation and pollution problems. Perhaps it isn't obvious that seamless roads, thriving trees, proper drainage, and clean air attract people to an area. In order to achieve redevelopment, Fort Point needs to strive toward symbiosis between nature, man, and its urban form. Though I chose my site to illustrate juxtaposition between the east and west, I observe that each side experiences the same struggle against nature.

Every water droplet in Fort Point is part of a greater system. The “hydrologic cycle,” as Spirn presents, constantly flushes precipitation through the earth, where it is absorbed by plants and filtered by soil, and sent back to the ocean, where it once again joins the atmosphere. The city disrupts this cycle by prohibiting water from reaching the soil. Topping that, urban wastes introduce pollutants into the flow of water. Like so many urban areas, Fort Point is plagued by water. In pointless combat, water damages streets and buildings and Fort Point poisons the water with its urban runoff.

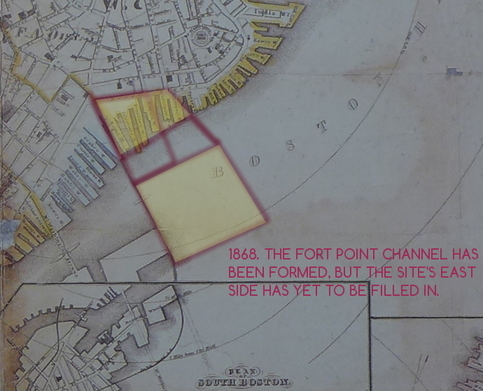

James Slade, Plan of Boston, Corrected under the direction of Committe on Printing of 1861, 1862.

James Slade, Plan of Boston, Corrected under the direction of Committe on Printing of 1861, 1862.

Sandy flatlands lie far beneath the dense streets and red-brick lofts of eastern Fort Point. Indeed, this section of my site isn't mentioned on maps from before circa 1880. I gather that, after the land had been filled in, the east side became a hub for industry. I presume the channel served as a mechanism of wastewater disposal when east Fort Point's factories were first constructed. From the same maps, I notice that the western side of the channel was lined with wharfs before the east was filled in. I suspect that filling Fort Point may have devastated the channel's natural environment and eliminated the possibility of a fish enterprise. I envisage historically that the west side followed the east's model of commercialization. In a time when water pollution was not a consideration, and with both sides acting as centers of commerce, the channel must have been a melting pot of urban pollutants

Relying on good faith: from left, drain on west and east side of the Fort Point Channel

Relying on good faith: from left, drain on west and east side of the Fort Point Channel Outland from the South Boston Public Works building, the Fort Point Channel transports treated combined sewage to Boston Harbor. East and west of the channel, you can find sign-postings disclosing that street water is drained directly to the harbor. I expect that after a storm these drains lead directly to the channel. Spirn explains that sediment and pollution in urban water systems can deoxygenate water, which may eventually lead to a shift in fish species (Spirn 210). Discharging storm water directly into the harbor will obviously draw pollutants from the city into the water. Pollutants from storm drainage and even snow-melt can accumulate and begrime aquatic species' environments – hence the illustration of fishes on the “don't dump” signs.

West side: a well-functioning drain near the Harborwalk

West side: a well-functioning drain near the Harborwalk  East side: a drainage pipe and cracked sidewalk.

East side: a drainage pipe and cracked sidewalk.

Standing on the west bank, between Seaport Boulevard and Congress Street, I spot a drain lying at the bottom of a brick basin. There's a trace of luminous white salt between the drain and a neighboring pile of snow, indicating that snow may have been piled strategically to reach this drain as it melts. In any case, I find no indications of warped foundation. It appears the drain has been recently built and inset deliberately to collect water. The historic buildings on the east side often have drain pipes running from their gutters. One particular pipe on A Street, near its intersection with Congress Street, cuts right into the sidewalk. Close to the pipe, a large cracks spans the paving – this may be due to leaking water from the pipe that causes the concrete (which is slightly porous) to expand. As far as I can see, it's unusual to happen upon a well-functioning drain in Fort Point. I find sunken foundation, cracks in the pavement, or pooling at nearly every street-corner – especially on the east side.

West side: pooling water.

West side: pooling water. East side: pooling water: left, google maps - right, own photo.

East side: pooling water: left, google maps - right, own photo.

(©2014 Google · Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agency · Imagery Aug 25, 2013.)

I turn another street-corner, now on the west bank of Seaport Boulevard, and my eyes fall to a pool of water by the road side. Why, I wonder, isn't the water collected by the drain? Upon inspection, I notice there's a pothole in the road that accumulates sediment and water. Roads on the eastern side face the same issues. On the east side, I discover an anonymous alleyway between Farnsworth St. and Thomson Pl. in which water pools in the middle of the street. Comparing with Google Streetview, this appears to be a persistent problem for the alleyway. Drainage pipes run from the gutter to the ground level, aiming for the sewers, but instead the road has sunken and large puddles seep into its foundations.

Often filled-in land faces structural issues, as the water seemingly tries to reclaim its belongings. Spirn delineates the disequilibrium of filled-in land “whose stability depends upon its contents and length of time it has been in place” (Spirn, 100).

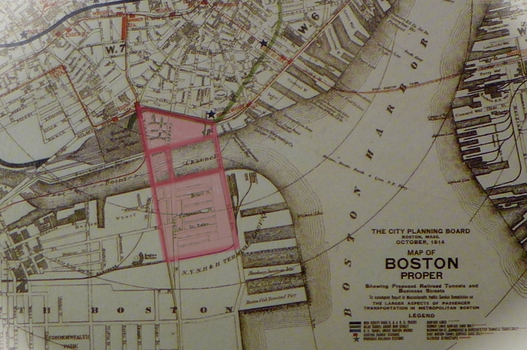

"Map of Boston Proper," City Planning Board, Boston Mass, October 1914.

"Map of Boston Proper," City Planning Board, Boston Mass, October 1914.Although I cannot pinpoint the exact time when Fort Point was filled in from the maps I've seen, I can finally draw my site's boundaries entirely on land in this map from 1914. Without extensively researching the chronology, I believe that eastern Fort Point has stood for over a hundred years. From my observations, the buildings in Fort Point appear to have a strong basis and their foundations have not lowered. Luckily, most buildings in Fort Point seem to be intact. Yet both sides of the channel contain a great deal of structural instability in their roads. This may be due, in part, to the high-traffic of Fort Point combined with the structural issues faced by filled-in land that is saturated with water.

You can see here on Atlantic Avenue, between Congress and Seaport, the sidewalk has sunken beneath the curb. Salt residue is left on the sidewalk by evaporated water that drifted towards the sunken curb.

West side: sunken pavement.

West side: sunken pavement.I assume that street water seeps between the unmortared bricks of the sidewalk and causes the upper levels to lower. This may be especially pronounced here, as the street lies above underground tunnels, including the T and the 93 – thus the streets are probably held up in part by supports. It follows that the thin layer of earth beneath the sidewalk may suddenly collapse onto its support system when too much water collects. Fort Point, and other filled-in areas, tackles foundational issues from improper drainage and the abundance of water.

I also see alligator cracks on the left of the "West side: pooling water". Elkins defines alligator cracks as the result from road overuse or thin road surface (Elkins, 28). These cracks jar the surface of Fort Point, especially at intersections of large roads. Both sides of the channel contain stripped roads. “Roads are stripped – when the underlying layers lose their bond with the top asphalt layer. Trucks can strip pavements, and so can storms” (Elkins, 33). Interestingly, both sides seem to have a layer of stone cobbling beneath the upper asphalt. The eastern example appears more extreme, but the asphalt's purpose is unclear. Perhaps the asphalt was used to mend some foundational issue with the road? The asphalt has rough edges and lies near protruding tree roots, suggesting that the asphalt may have been laid to remedy major cracks in the road surface. In the western example, the road has torn away in a patch, clearly revealing the underlayer. I think the road traffic ravaged a chunk of the top layer in the western example.

West side: stripping.

West side: stripping. East side: stripping.

East side: stripping.

Both sides have a layer of stone lying between the asphalt and the soil. That layer of stone, asphalt, and compacted soil traps heat, shaping microclimates of relative heat in Fort Point. Each side of the channel meets Spirn's description of the city: “concrete, stone, brick, and asphalt, replace the natural plant cover of the countryside” (Spirn, 52). The interaction with these materials, urban energy, and the sun can create areas of more or less heat within the city. I see the sun reflecting off the surface of Congress St. on the west bank. I notice the snow has mostly melted along the main roads in my site: Atlantic, Congress, Summer, and Seaport. But other areas have the ocean's cold nip in the wind and more residual snow and ice.

East side: a patch of cold.

East side: a patch of cold.

East side: weathering fire-escape.

East side: weathering fire-escape. West side: sunken pavement.

West side: sunken pavement.

Specifically, the only plot of land in my site that remains mostly coated in snow lies near a playground on the east side. This playground rests on Boston Wharf Road, south of its intersection with Seaport. The play equipment and a basketball court sit atop a windy patch of grass, in the shade of tall brick buildings. This area doesn't receive much sunlight and the open grassland doesn't absorb heat like concrete and urban materials do. Hence, I believe this area has its own microclimate - similar to that at the water’s edge - that still supports a layer of snow despite the rising temperature.

I imagine that the proximity to the ocean brings in precipitation with relatively high concentrations of salts. Much of the construction on Fort Point makes use of iron that reacts with the rain water, oxidizing into rust. Thus, you see many rust stains on the bridges and pipes and fire-escapes from the rough, weathering maritime climate.

West side: street canyon.

West side: street canyon.

I emerge from South Station bundled up in my coat, and feel the cold and stagnant against my face. I look out onto Atlantic Avenue where the Rose Kennedy Greenway separates me from the tall westerly buildings lining Purchase Street. To my right, the east, staggers the tallest building in sight. A gentle northwest wind sweeps perpendicular to traffic-ridden Atlantic Avenue, creating a broad, as Sprin describes, “street canyon” where exhaust fumes are trapped (Spirn 57). Near the east side of the intersection of Atlantic and Seaport, there's a hotel with an awning. Like we mentioned in class, the awning accumulates fumes from the street. I even notice the stench as I walk beneath it. Take a few steps back on Atlantic Avenue and turn right on Pearl St. The left-hand wall is covered by some ventilation system, that graciously ejects air into the alleyway. The design of the roads and alleyways seemingly overlooks the accumulation of air pollutants.

West side: ventillation into Pearl Street.

West side: ventillation into Pearl Street.

Across the channel on the east side, the large streets lie parallel to the northwest wind. Walking down Congress St. away from the water, my hair blows forwards and presumably the exhaust fumes follow, but I can't smell them, and the air seems cleaner. The dense grid of smaller roads and tall buildings without much traffic appears to control air pollution. However, on the same nameless alley between Thomson Place and Farnsworth Street where the water pools in the road, there's a multistorey parking lot that opens into the alley. Even on a peaceful Sunday afternoon, the alley reeks of emissions. What can Fort Point do to purify its air?

East side: parking lot in alleyway.

East side: parking lot in alleyway.

Behold in the photograph above, beside the parking lot on the right, there are trees. Trees are wonderful elements of the urban garden. As Spirn states, “trees on streets represent most cities' greatest investment in plants. They influence the climate, air quality, and appearance of the places where people live and work” (Sprin, 188). Certainly, strategic tree-planting can improve urban air purification.

The trees in Figure "East side: parking lot in alleyway" lean south-east, towards the morning and afternoon sun. In fact, the monotone height of buildings on the eastern side forces most trees beyond a certain height to bend towards the center of the streets. Otherwise, the trees live in the shadows of buildings, starved of the sunlight they require to prosper.

Left, trees of the west. Right, trees of the east.

Left, trees of the west. Right, trees of the east.The western side of the channel is more broadly oriented. The roads are wider, there's more greenery. The trees on the western side are evenly planted, not nearly so tall, and about even height. In Fort Point, I observe that the orientation of trees (whether they will grow upwards, to one side or another) hinges upon road structure. Road structure governs light and shadow. The denser streets of the east are more shadowy and only taller, so trees must bend to meet the sun. On the west, the trees are shorter than their eastern counterparts. Because the roads are broad and more light is available, western trees grow evenly upward, spreading with radial branches #Image. Neither side contains the beautiful, full foliage that city-dwellers unknowingly long for.

Woe be ye teacup tree!

Woe be ye teacup tree!The trees I've mentioned are street trees. They live in limited small plots of soil at the edges of roads. Spirn laments on urban plantlife, “many plants can't survive at all; others survive in a dwarfed, distressed condition” (Sprin 175). This is exactly the case in Fort Point. On the west, most trees can't seem to grow past 10 feet. Spirn's “teacup effect” supplies us with some insight - that is, urban trees that are pitted in compacted soil often unable to acquire enough water, or dispel excess water (Spirn, 192). In that same nameless alley from Figure # on the east, this petite pine sproutling projects its roots from the dry soil in a vain attempt for survival.

No parking on this tree!

No parking on this tree!

©2014 Google · Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agency · Imagery Aug 25, 2013.At the north-east end of Thomson Place, a road lined with diminutive street trees, I chance upon a small, deliberately chopped stump. My mind fills with questions. Could this tree have fallen? Could it have been growing into the road? Of course, I immediately compare the site on Google Streetview and make an interesting discovery. Earlier this year, there's no stump at all, rather a “no parking” sign sits in its place. Could the sign have been replaced by a short-lived sproutling? I wonder, could the tree have been chopped to make way for the sign? In either case, we see an example of Fort Point imposing itself on nature. It appears these trees were planted with the purpose of beautification. They're seen as mere decorative features, and don't receive appropriate appreciation of their value to the environment.

East side: tree stump on Thomson Place.

East side: tree stump on Thomson Place.

On Summer St, where it runs over Boston Wharf Road, I witness another tree-fence interaction much like the one from our field trip. Although I initially empathize with the tree, I realize these interactions are a symbol of hope. The fence dilapidates the tree, and the tree dilapidates the fence. But imagine if we change that verb – and dilapidates become accommodates. Fort Point has a long way to go, but I have faith that nature and Fort Point can coexist.

East side: a sign of hope?

East side: a sign of hope?

Of course, natural processes underlie every concrete mask and brick facade that we build. Fort Point is afflicted by compacted soil and pollutants. The interaction of rain and water with Fort Point's filled-in natural environment has created a number of obvious, unattractive cracks in the pavement and sidewalks. Fort Point, the rest of Boston, and many maritime cities all face similar issues. In every case, problems stem from overlooking, or not fully addressing, natural processes. Modern technology allows us to predict the climate and understand the lay of the land better than ever before. Fort Point, Boston, all of the United States must embrace these advances to use nature to the city’s advantage. The future city accommodates the forces of nature.

Bibliography:

Elkins, James. How to Use Your Eyes. Routledge: New York, NY. 200: pp. Vii-xi, 12-19, 28-33, 170-175.

Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. Basic: New York. 1984.

Back to top

East side: pooling water: left, google maps - right, own photo.

East side: pooling water: left, google maps - right, own photo.  East side: stripping.

East side: stripping.East side: a patch of cold.

West side: sunken pavement.

West side: sunken pavement.East side: parking lot in alleyway.

Woe be ye teacup tree!

Woe be ye teacup tree! No parking on this tree!

No parking on this tree!East side: a sign of hope?