I take a seat on one of the icy benches lining Dorchester Avenue. The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston reaches up towards the late afternoon sun behind me and cast its shadows upon the tenebrous red-brick warehouses across the Fort Point Channel. I'm drawn to discover what connections lie beneath the divergent surfaces of both sides of the channel, to discover how these areas coexist, so I set boundaries that emphasize that coexistence.

The contrast in culture and architectural style between both sides of the channel reminds me of Mud Island back in Memphis, Tennessee, where I went to high school. Memphis's Wolf River was diverted in the 1980's, creating an island that had previously been marshland. Mud Island is an affluent grid of quaint cookie-cutter row houses, all-natural grocers, and ritzy tanning salons – all just a stone's throw from the chaotic diagonal streets and run-down tenements of downtown. I've found that a natural break like the Wolf River and the Fort Point Channel has the power to alienate two areas that are very close geographically. But with that proximity, I feel there must come some sort of dependence (whether economic, legal, or social) that keeps the areas integrated.

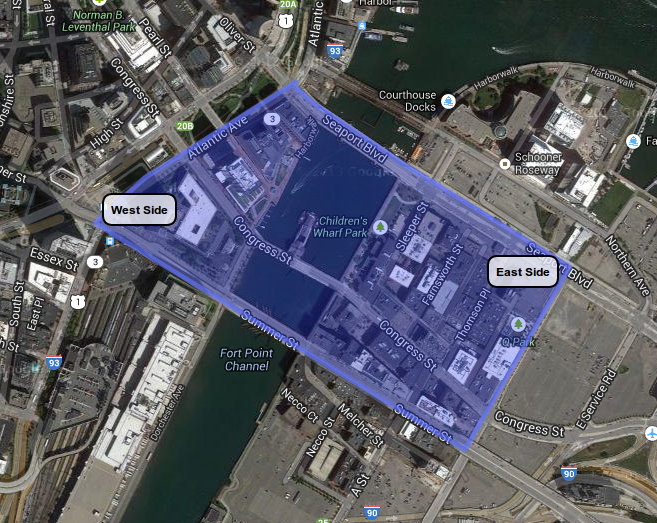

Figure 1: ©2014 Google · Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agency · Imagery Aug 25, 2013

Figure 1: ©2014 Google · Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agency · Imagery Aug 25, 2013

I define my boundaries in the hope that they provide a quintessential piece of each side of the Fort Point Channel. From South Station, my site extends northeast along Atlantic Avenue until it meets Seaport Boulevard. These streets box in representatives of the west side: an entrance to South Station, a few lunch places, office buildings. Onward from that intersection, turn right on Seaport and continue across the water until we meet Boston Wharf Road, make another right, and follow Boston Wharf Road southwest to Summer Street. The larger roads (Seaport, Boston Wharf, and Summer) enclose a dense area of smaller roads and alleyways which contain a bunch of tech companies, restaurants, and lofts – these provide a slice of life on the eastern side. Finally, the southern boundary runs back along Summer, across the channel, to meet Atlantic Avenue. I feel this variegated trapezoidal segment of Fort Point captures a number of different land uses, road sizes, and architectural styles that will allow me to comparatively analyze the both sides' integrated development.

Now that I've set my boundaries, I take a look at the road patterns on my site. The roads on the west side of the channel form unusual angles with each other. On the other side, the streets are generally dense and gridded. The Fort Point Channel forms a natural location for a “break” – as Grady Clay describes, “an abrupt visible switch in the direction and/or design of the streets” (42). Once again drawing a comparison with Downtown Memphis, historic street patterns can become wonky as a grid approaches a body of water. The west is close to Boston Harbor, a significant historical site, suggesting that the streets were laid a long time ago. However, the east side, like Mud Island, may have been filled in, explaining the more regular street pattern.

View of the west side - Air Intake Building (Mural by Matthew Ritchie in collaboration with Boston ICA).

View of the west side - Air Intake Building (Mural by Matthew Ritchie in collaboration with Boston ICA). The differences don't stop with road plans. The western side borders the Financial District – one notices its wealth from the grandiose ICA-funded mural on the Air Intake Building in Dewey Square and the presence of enormous, prosperous corporate buildings. The west is far from desolate; there's always a crowd of taxis and pedestrians buzzing about South Station. In contrast, the east by no means possesses the bustling and vibrant culture of the west side – walking around, you see one person on the east for every ten on the west. The east is composed almost entirely of repurposed red-brick warehouses with the exception of one or two glass buildings on the waterfront and the playfully decorated Children's Museum. There's a great deal of chipping paint, crumbling brick, and rust on these old warehouses. Given that the east isn't all that populated and has a rough architectural aesthetic – I wouldn't expect all the high-end restaurants and bourgeois grocers.

The east and west complete each other. Together they are isolated and integrated, old and new, glass and brick. My site provides a fascinating piece of Boston – two districts made culturally distinct by physical separation. I feel there's a great deal to learn from the development of my site and the mechanisms of interaction between each side. I set boundaries that capture all that I find most exciting, significant, and curiosity-inducing about Fort Point. I hope whatever I disclose within those boundaries, which express my site's varied composition of styles and ways of life, will lead me to understand the direction of Boston's future.

Reference:

Clay, Grady. Close-Up: How to Read the American City. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL. 1980: pp. 11-16, 38-65.