Time through Fort Point

I stand on Summer Ave. bridge. To my left I see the towering concrete, brick, and glass of the west and to my right I see the shorter converted warehouses of the east. My camera strap whips like a flag in the wind. I step a few paces backward and press my finger into that cool metal button.

Figure 1: Both sides of the channel

Figure 1: Both sides of the channel Click, I've captured a million layers of seconds, people's lives, minutes, natural processes, hours, industry. I remember being drawn to Fort Point by the contrast between each side of the channel – I wanted to understand how each side shaped the other. I discovered that both sides had a similar industrial history, but aesthetically the west has been almost entirely recreated since then and the east practically remains the same. Still, beneath the west's sparkling skyscrapers, I find the remnants of old wharves and industry and transport that hint at its connection with the east side.

ii. in memory of the past

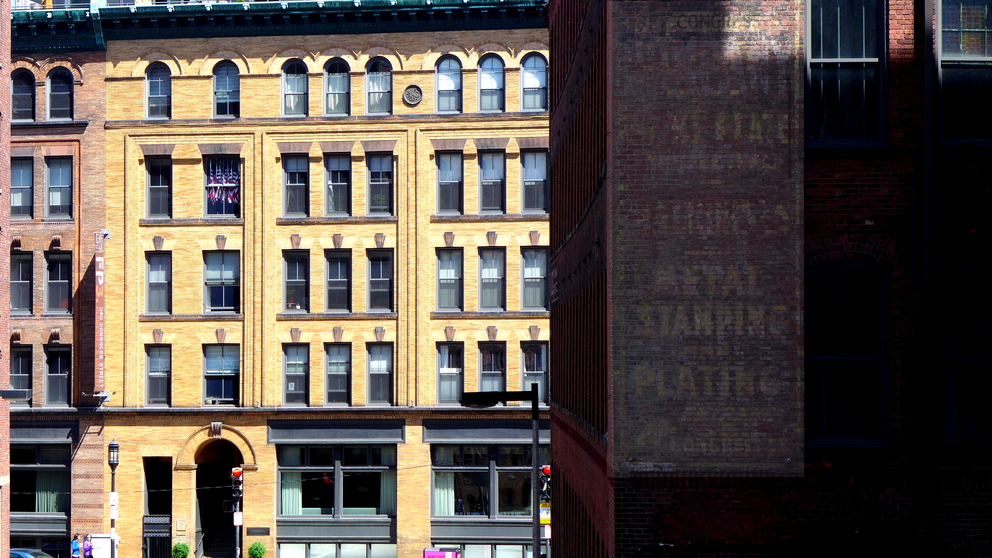

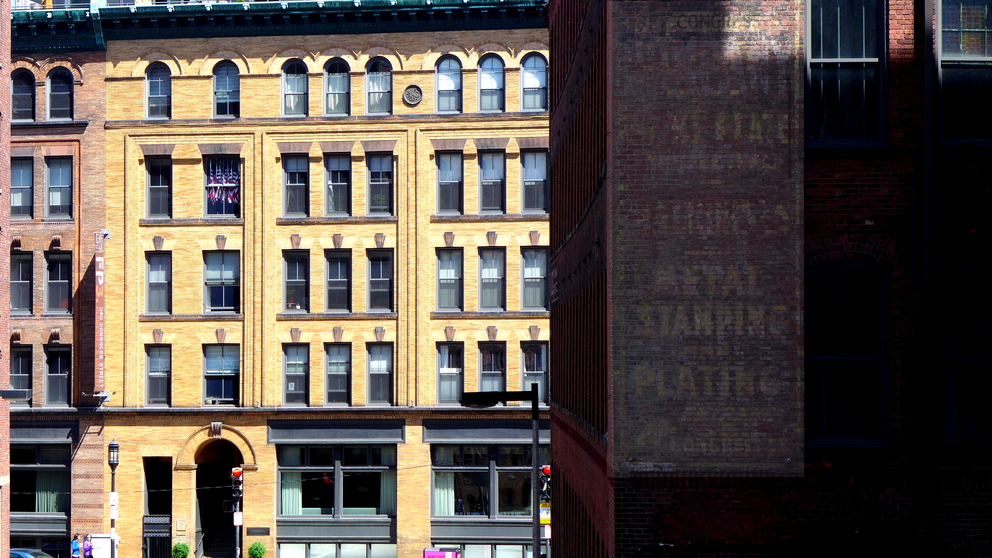

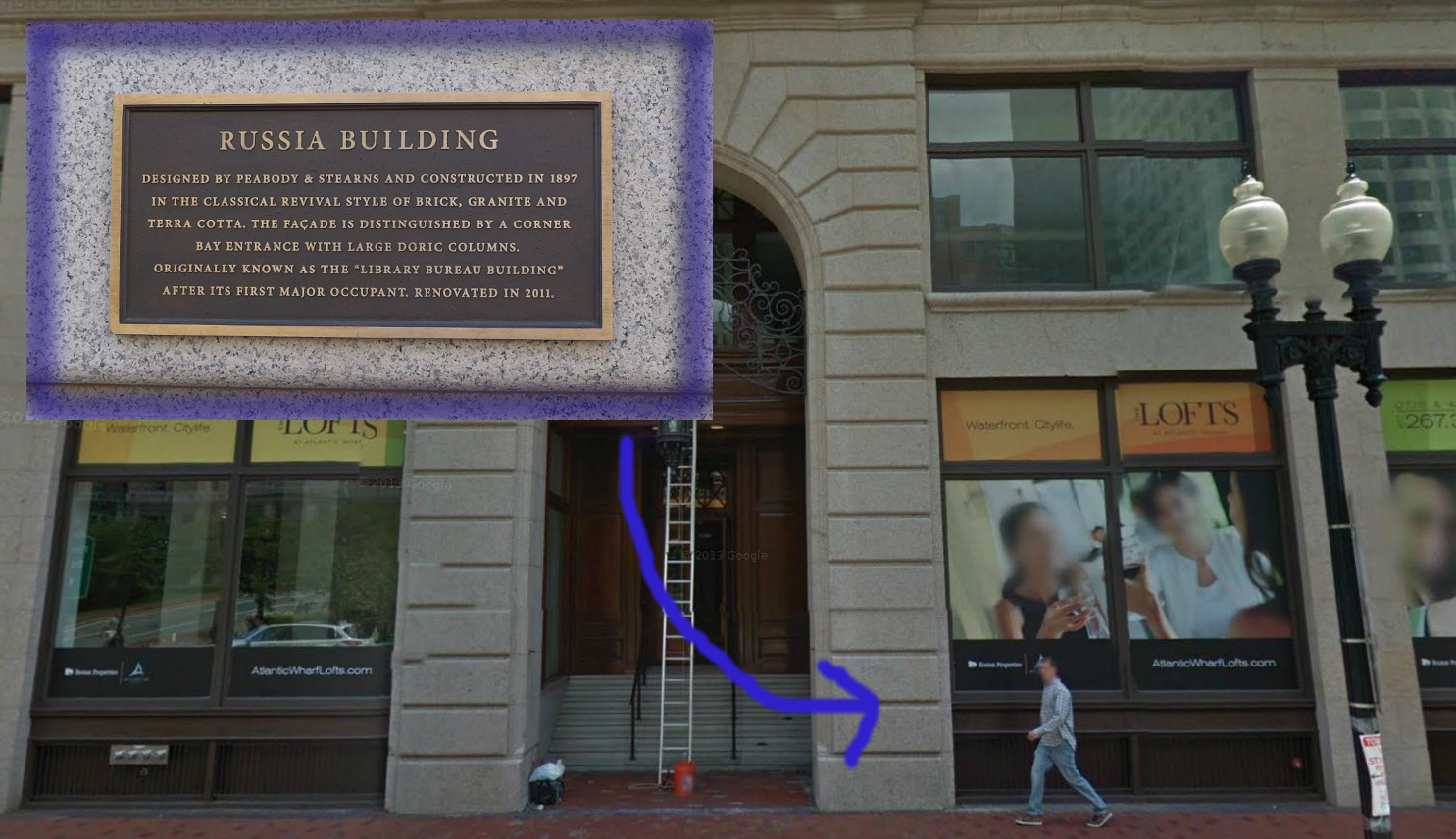

Artifacts are abundant in the urban landscape – every billboard, every shop, every tree stump is an artifact in one way or another. So I zeroed in on a form of artifact that struck me: plaques, advertisements, and memorials. I noticed that before fabric billboards, advertisements were painted directly onto buildings. Since most of the west side has been rebuilt, I couldn't find any traces of this on that part of my site. However, the many eastern buildings are plastered with fading white lettering. I can make out company names painted onto the buildings, some of which correspond with the Sanborn maps from the first half of the 20th century. Plaques are particularly telling to me – for, as mentioned in class, they give us a sense of the history of a place, how significant that history is, and who cares for the place. Every plaque is positioned with purpose. In addition to its explicit message, we can glean information from when and where the plaque was placed. That may be to create a sense of pseudo-historical charm or perhaps to simply acknowledge a company or person.

Figure 2: Painted label on a building and BWC medallion.

Figure 2: Painted label on a building and BWC medallion. On the eastern side, it's difficult to walk a block without seeing half a dozen Boston Wharf Company medallions. As evidenced by the old maps, the Boston Wharf Company once owned most of the east side. At some point between 1950 and 1992, the company vanished from the east side leaving its many wool warehouses and other industrial buildings. I hypothesize that the company went bankrupt with the advent of synthetic fabrics and the dwindling wool market. So why is the Boston Wharf Company celebrated with these medallions? Often made of copper, the medallions read “B. W. Co” and the date that the building was constructed. From the appearance of the plaques and the use of copper (which was more inexpensive at the time), I believe they were ornamentally attached to the buildings when they were first constructed. It was a show of pride to belong to a company that was then prosperous. Interestingly, the dates are not always linear: I noticed a 1891 plaque sandwiched between two 1900s. I presume that in the initial stages of development a warehouse was built here and there around which more warehouses were built in dense rows as the need for manufacturing and storage space increased.

Figure 3: Plaque marking site of the Boston Tea Party.

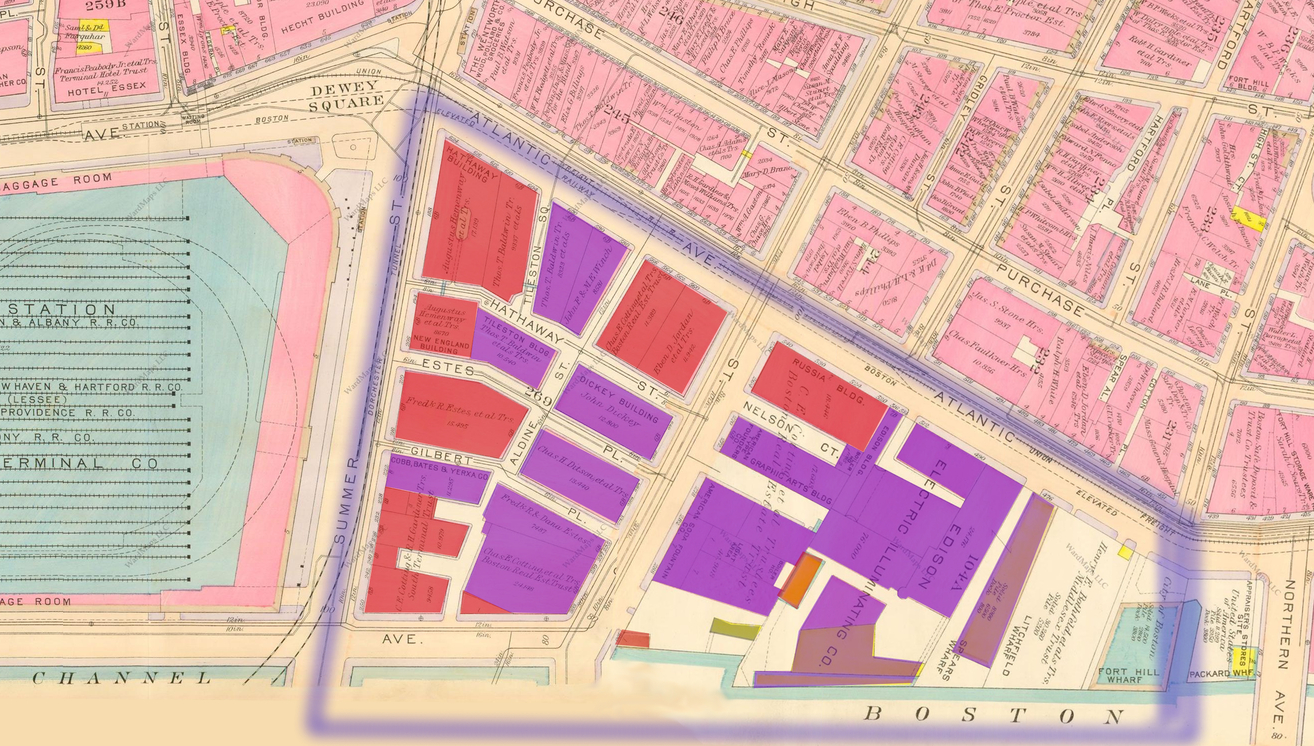

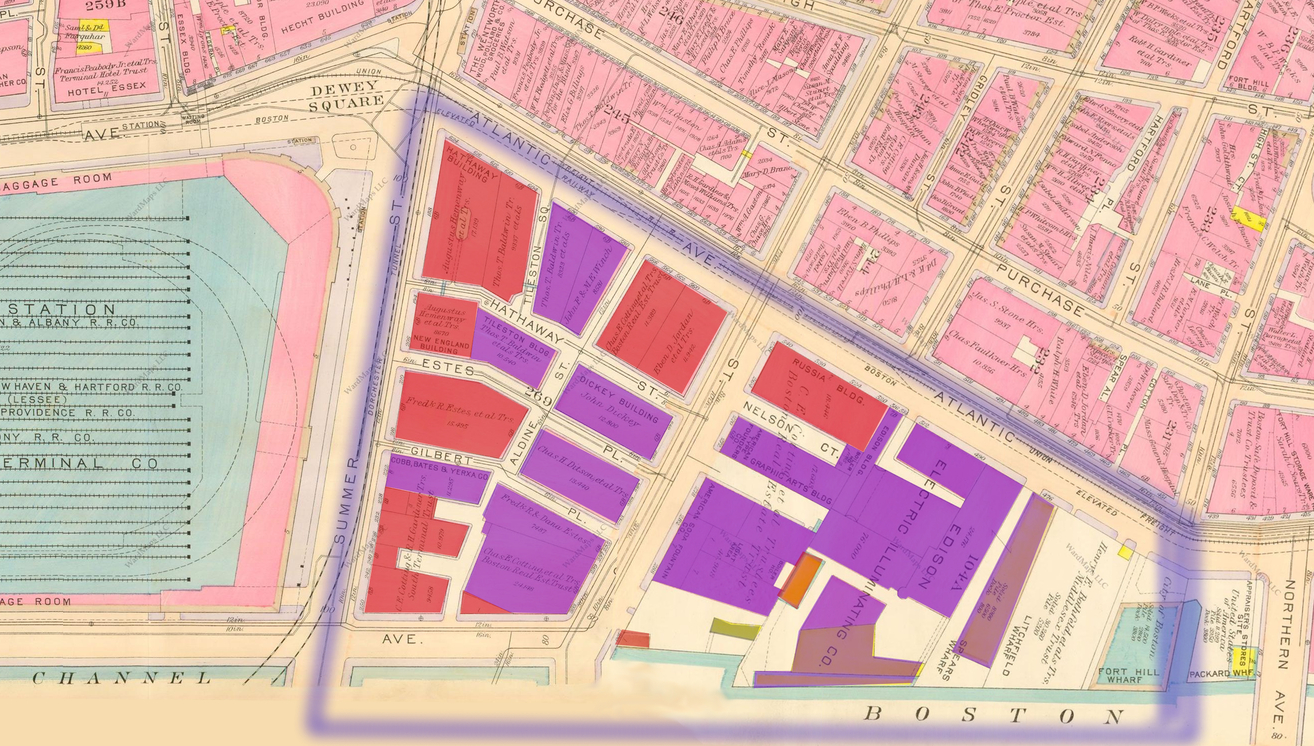

Figure 3: Plaque marking site of the Boston Tea Party. Today we're left with few signs of the west's industrial past. Rather, the west makes a conscientious effort to celebrate its non-industrial history. I noticed two plaques that shed some light on the reputation that the west desires. The first, on the waterfront near Seaport Boulevard is a historical plaque that acknowledges the site of the Boston Tea Party. The apparently tasteful plaque, constructed in a modern style, is just minutes walk from the loud and tacky Boston Tea Party boat-museum on the Congress St. Bridge. The second is on Atlantic Avenue. A plaque rests on a granite archway that belongs to some loft spaces. The plaque lionizes the Russia Building, which was constructed in 1897. From reading, one imagines a rather grand building. But I see a impressive, festooned building being out of place at the time. I checked the building on Google Streetview to see if the lofts were residential.By some luck, Google maps had captured the building in 2011 during its renovation. The plaque hadn't yet been placed (unsurprisingly, as it mentions the building was renovated in that year). I believe the lofts had recently been converted from offices into residential spaces in 2011 and the plaque was designed to lend the building the appeal of history and grandeur. Looking back to the 1917 map of the west, we can see the Russia Building was there and being used for commercial purposes. This gives me a sense that, around the time when the east was being developed, the west started to make a slow shift from its heavy industrial past. Both plaques seem to exploit this shift in their promoting the west as a now-and-always posh commercial district.

Figure 4: Atlas of the City of Boston, Boston Proper and Back Bay, from Actual Surveys and Official Plans, 1917. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. G. W. Bromely & Co. 1917. Print.

Figure 4: Atlas of the City of Boston, Boston Proper and Back Bay, from Actual Surveys and Official Plans, 1917. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. G. W. Bromely & Co. 1917. Print. Figure 5: Russia building plaque. ©2014 Google · Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA · Imagery June 16, 2011

Figure 5: Russia building plaque. ©2014 Google · Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA · Imagery June 16, 2011

Something of note, that affects both sides of the channel, is a distinct lack of connection with the place's history in time. Both sides of the channel were industrial centers. I would expect some heavy duty machinery at least, but both sides have transformed into gentle centers of modern commerce. The wealthier west specializes in finance and the east is a budding

Figure 6: South station.

Figure 6: South station. tech center. The location of the railroad never changed through time, however. So we've discovered, transportation is key to all of the developments that occurred in Fort Point thus far. Throughout the maps, we see new modes of transportation coming in, but the railroad was always there and always expanding. Dolores Hayden mentions that “something as basic as a railroad or streetcar system changes the quality of everyday life in the urban landscape, while marking the terrain. For some it provides jobs in design, or construction, or operation, or maintenance; for others, it makes a journey to work through the city possible” (Hayden 22). I believe the railroad once brought many jobs to immigrant workers when it served the manufacturing companies in Fort Point. Today, with the addition of the Boston T, it serves a new purpose. Once primarily a freight line, the railroad brings commuters to and from South Station. That is, people come in from Greater Boston on the train to work in Fort Point.

Figure 7: Independence wharf.

Figure 7: Independence wharf.With commuter trains brought commerce of a new variety – a far cry from the trade ships and wharves that lined the west side in the 19th century. In fact, the primary remaining evidence of wharves on the west side is the proximity of the channel. The Fort Point Channel itself is a trace of filled in land. The mention of the Boston Tea Party alone clues one in – how could a ship of significant size have ever navigated this little channel? The filled in wharves seem so innocuous – one wouldn't assume the west used to be an extension of the main harbor. But the little channel, with its cracked stone walls suggests artificial intervention on the landscape. There's an office building that calls itself Independence Wharf at the corner of Seaport and Atlantic. The wharf in that location used to be Fort Hill Wharf. The land is longer technically a wharf, there's nowhere to dock ships, so I suppose “Independence Wharf” just had a nice maritime ring to befitting a waterfront office building.

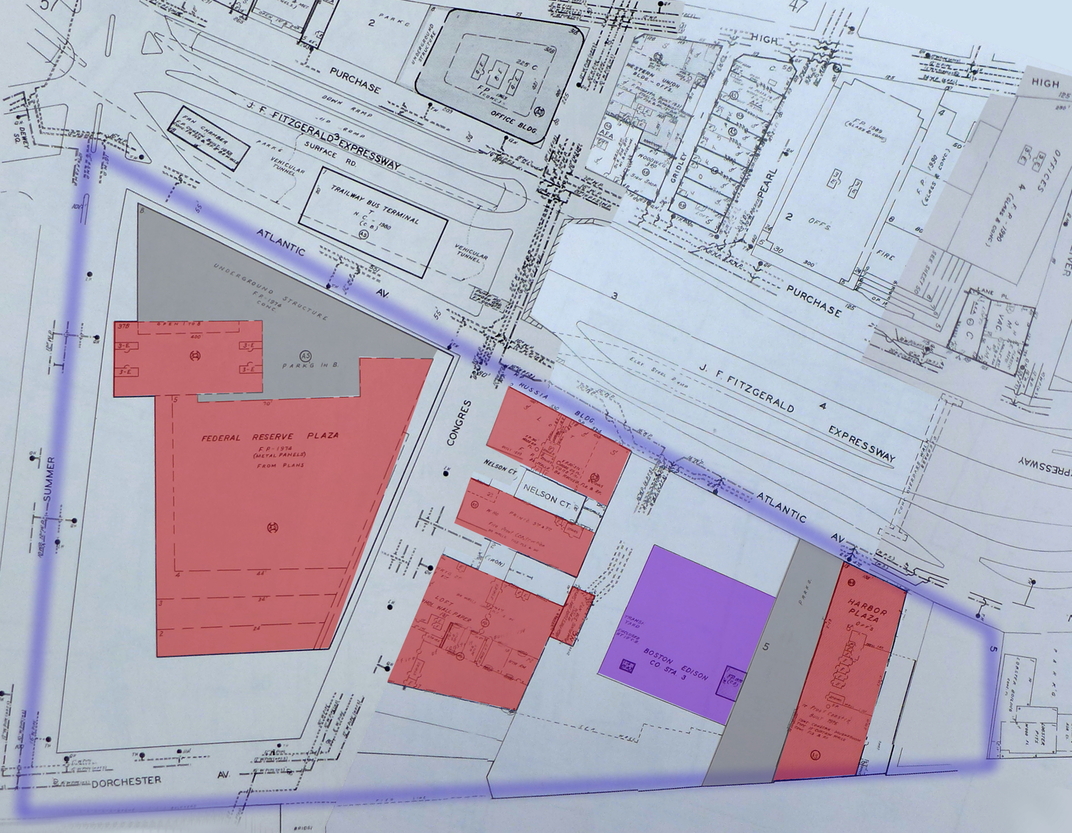

Figure 8: Sanborn Map Company. Boston Volume 4, 1950. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. Sanborn Map Company. 1950. Print.

Figure 8: Sanborn Map Company. Boston Volume 4, 1950. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. Sanborn Map Company. 1950. Print.

Figure 9: Howe's Leather Company. ©2014 Google · Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA · Imagery June 22, 2011

Figure 9: Howe's Leather Company. ©2014 Google · Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA · Imagery June 22, 2011

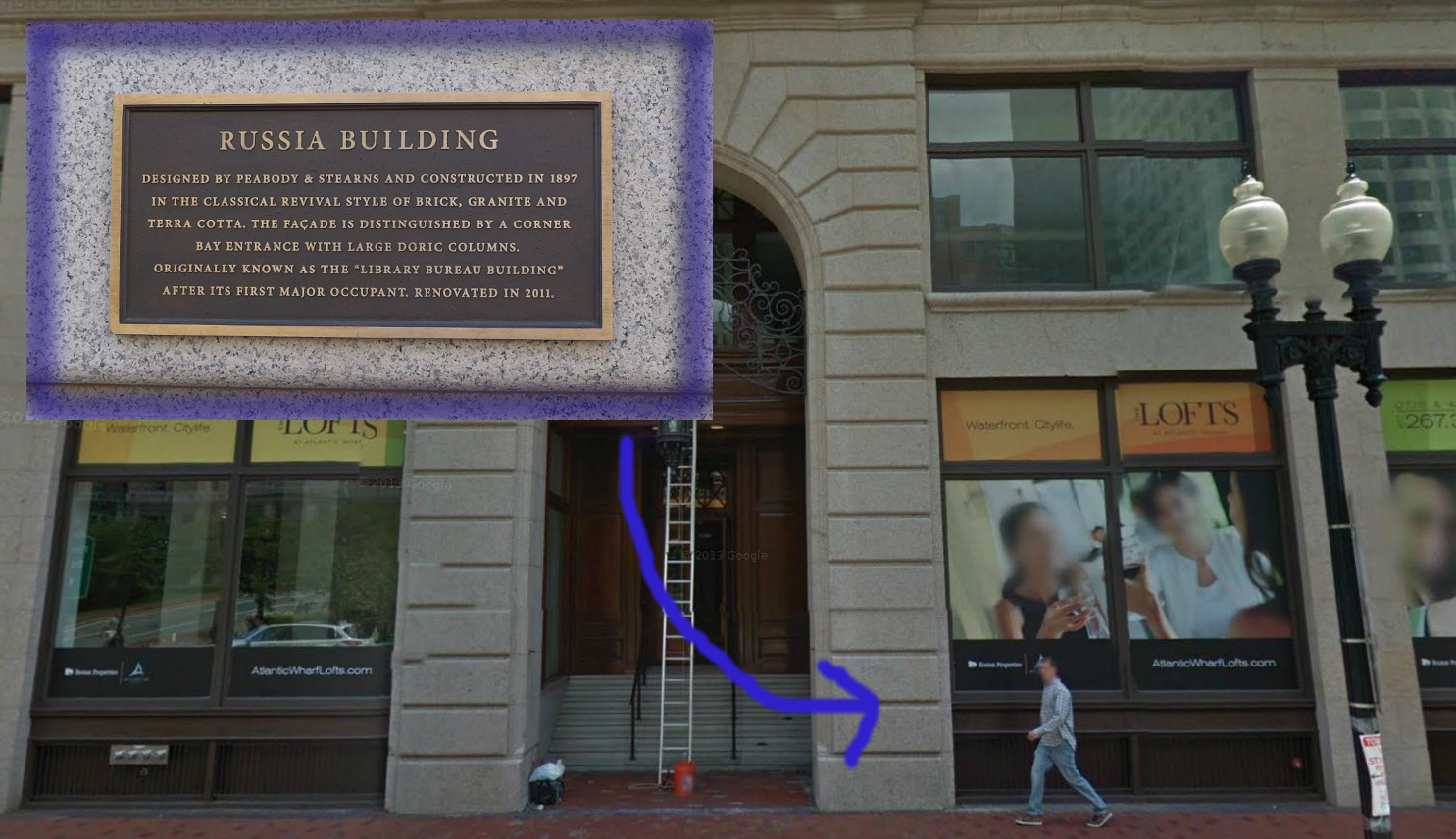

Although almost every building on the east side still stands, very few buildings in Fort Point serve their original purpose. We see tons of technology companies like Thomson Reuters on Thomson Pl. that are obviously converted warehouses decked with loading docks and bricked-up windows. This is somewhat unsurprising, as most of the manufacture in Fort Point was directed at an obsolete market. I did find one exception, however. Near the intersection of A Street and Summer Street is Howe's Leather Company, which we first see on the 1950 Sanborn Map.

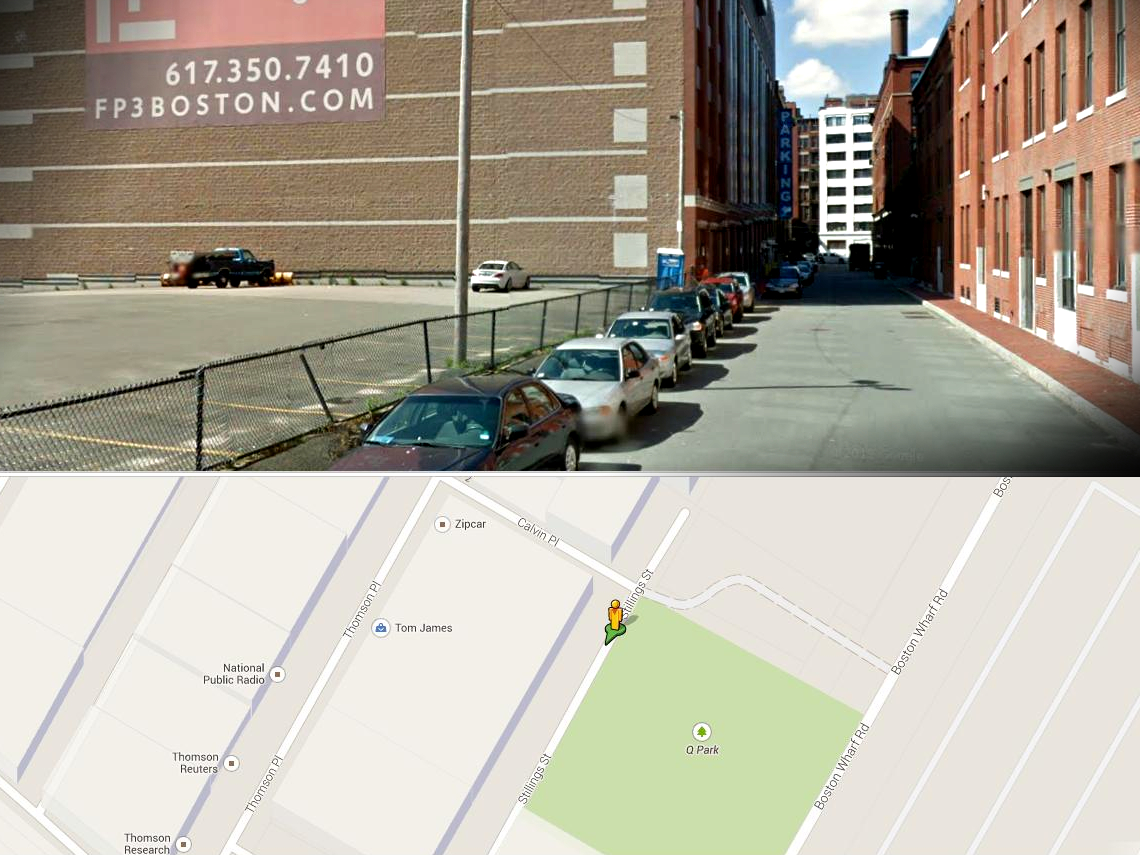

Figure 10: Torn-down wool warehouse, now parking lot.

Figure 10: Torn-down wool warehouse, now parking lot.

I've known leather is timeless for a while, but I'm surprised that this seemingly small tannery could have survived the area's bankruptcy. I imagine that the company was not owned by the Boston Wharf Company and was thus dependent on its own sales and didn't crash and burn with the decline of wool. Lack of a medallion further supports my hypothesis. Those buildings in Fort Point that were demolished have now become parking lots.

iv. now, back then, every moment in between

The warehouses that were demolished were either vacant in 1950 or wool warehouses. Near the intersection of A St. and Congress, I discovered a warehouse that was demolished in between two other buildings.

Figure 11: Many-layered site between two buildings.

Figure 11: Many-layered site between two buildings.This torn-down site first appears on my 1992 Sanborn map as a “transfer yard” surrounded by a wire fence. In this plot of land between these brick warehouses, time seems to stack itself. Let's consider the old buildings from the early 19th century to be the first layer. The demolition marks the second layer. Then on top of the demolished site is some piece of industrial technology from the 90's (perhaps a power generator?). The machinery is a third layer. As a fourth layer, there's a modern sticker on the machine that reads “safety first”. Each layer tells a bit of the story of its original purpose, repurposing, modern use, and reaction from people.

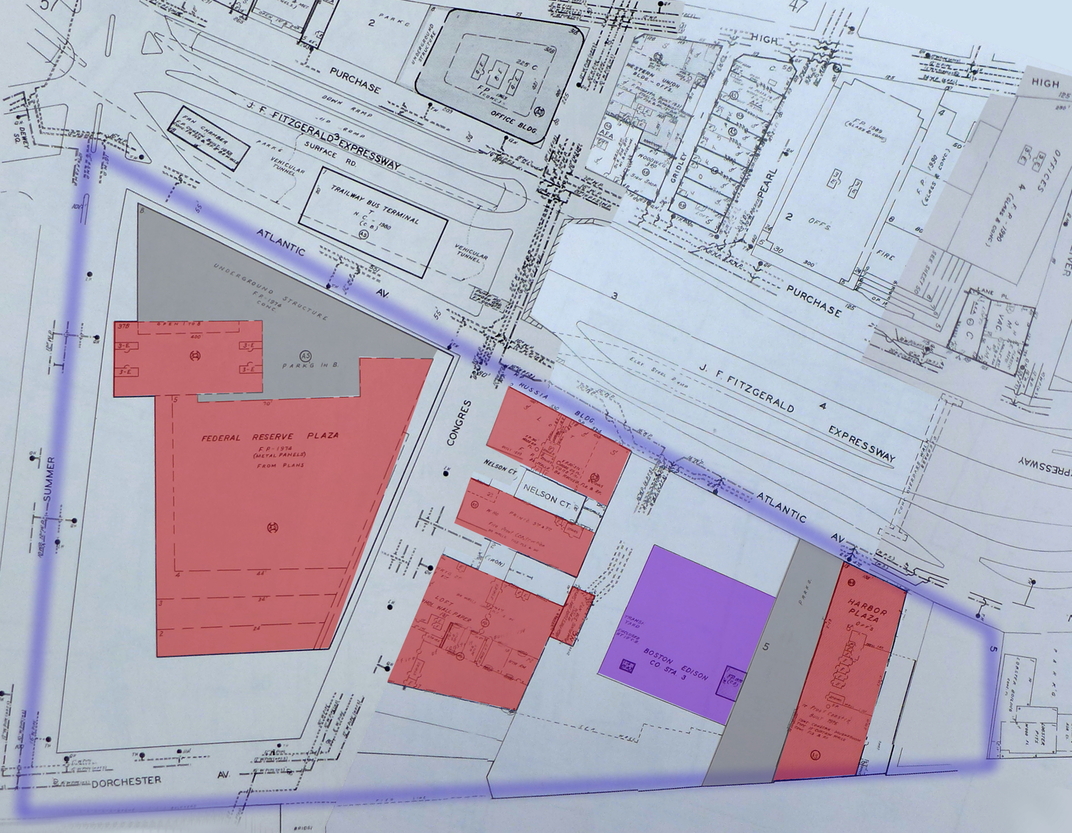

Many buildings were demolished on the west after 1950 to make way for the automobile and the Federal Reserve Bank.

Figure 12: Layered style on the west.

Figure 12: Layered style on the west. Most of these demolished sites were simply rebuilt entirely into modern commercial spaces. On both sides of the channel, I noticed a common architectural style that I believe is characteristic of redeveloped industrial areas. Many old brick buildings had been annexed to skyscrapers or extended with glass lobbies and lofts. I'd describe a view of Fort Point from afar as an array of dramatic rooftops. I say this because many brick industrial buildings now have modern glass additions sometimes towering up or slanting at a angles with the original brick.

Figure 13: Layered site style on the east.

Figure 13: Layered site style on the east.

The billboard in Figure 10 presents a layer in time. I imagine that advertisements would have been painted onto the outer wall of the missing building in the past. It's as if the demolition that occurred peeled back a bit of the city for modern times to get their hands on. I found another such chicken layered onto a drainage pipe of an old worn building on A St. Knowing that decals and advertisements represent the socioeconomic status and interests of modern residents, I Googled the image of the rooster to find its significance. Apparently it's the face of Bocoup, a new web design company that's opened on Congress St. The company also rents desk space and materials to “hackers” where they can socialize and implement their personal projects around like-minded people. It's like an artist's studio for computer scientists.

v. don't fight the future

Figure 14: Artist building in the east.

Figure 14: Artist building in the east.We mentioned in class that artists facilitated the transition between Fort Point's decline in manufacture and its becoming an innovation district. Artists' ability to create studios in the lofts of retired manufacturing buildings speaks to the utility and versatility of the original architecture. It's a trend noticed throughout history in literature and music that artists will move to a down-and-out area, open galleries, and bring culture to an area. Then upmarket commerce and posh flats chase the starving artists out (for instance, Simon and Garfunkel's Bleecker St. describes dirty poets and cheap rent in a street that's now a hip, expensive destination). I presume that such occurred in Fort Point circa the 1970s. To date, the area houses many galleries and art communities as well as the ICA. However, the art scene in Fort Point is not the grungy art that created the livability of the innovation district. Rather it's the kind of showy, expensive art that's created by the few who could afford the rising rent.

Figure 15: No playground! ©2014 Google · Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA · Imagery June 22, 2011

Figure 15: No playground! ©2014 Google · Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA · Imagery June 22, 2011

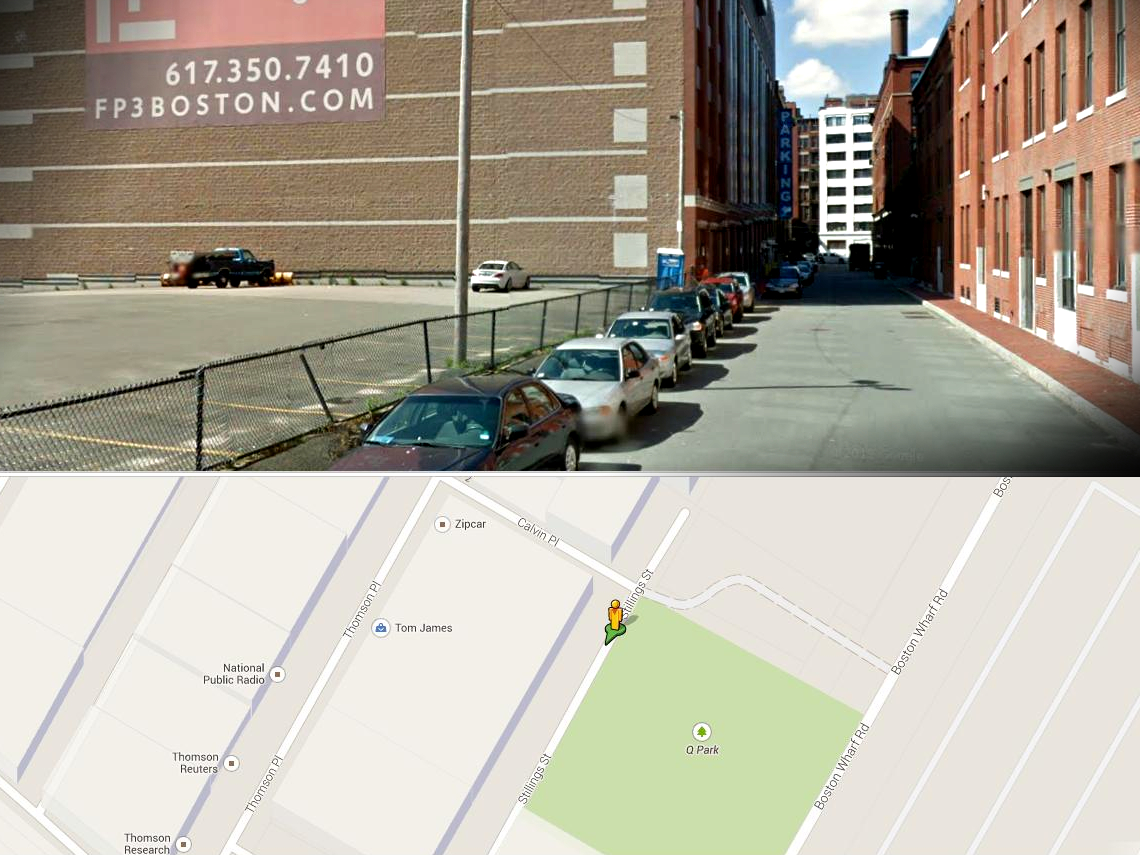

I discovered an example of redevelopment within just the past few years. Q Park lies beside Boston Wharf Road on the east side – it's a small plot of land with an innovative (although not that fun and a little painful) metallic playground and a basketball court. I cross-checked the site with Google Streetview and found that the recreational area was a parking lot in 2011. I'm reminded of Hayden, “it is city dwellers’ shared lifetimes that create an American sense of place. In scale and approach, this is the opposite of the top-down thinking that underlies urban design as grand-scale redevelopment planning practiced by American cities. There the understanding of history is often minimal, the practice often involves vast areas of demolition and new construction” (Hayden, 235). It seems that Fort Point's making an attempt to

Figure 16: Awkward playground in the east.

Figure 16: Awkward playground in the east.make the area more livable for yuppies and their families, but I think this playground is a bit of a failure. It's more attractive than it is functional and it's surrounded by the noise and traffic of main roads. It's been empty or close to it every time I've visited. That said, the Children's Museum does successfully draw families to the area and the proximity of transport, nice restaurants, and software companies are certainly increasing eastern Fort Point's appeal.

Figure 17: Sanborn Map Company. Boston Volume 1S, 1992. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. Sanborn Map Company. 1992. Print.

Figure 17: Sanborn Map Company. Boston Volume 1S, 1992. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. Sanborn Map Company. 1992. Print. The Financial District clearly has its claws in the west with its gigantic Federal Reserve Bank and bourgeois cafés. The Sanborn maps from 1992 show a far more empty west side than we see today. In the past 20 years the streets became filled with new lofts, hotels, and cafés. And in addition to the new ground space, the west has also expanded upwards (as seen in Figure X). I noticed when I first visited my site that the bustle of South Station brought a lot of people to the west side. Many people are coming to and from work. Many tourists arrive there and walk around. For some reason, it seems very few people make the venture to the east. The east is a place to live and to get lunch, but it doesn't have the popularity of the west. So where did that popularity come from in a place that was once industrial? Throughout time, we see a gradual shift in modes of transportation. People being able to get around became more important for the city than transport of goods. The west side transitioned to accommodate city people and it now hides its industrial past in the shade of its skyscrapers.

I fold my camera into its case and walk back toward the station. Anne Whiston Spirn states in the Language of Landscape that “losing, or failing to hear and read, the language of landscape threatens body and spirit, for the pragmatic and the imaginative aspects of landscape language have always coexisted” (Sprin, 11). I remember first setting eyes on Fort Point, and being transfixed by the old-world bricks and the sweet channel. I never imagined with what depth I'd come to understand the place. I feel that I've enlivened the language of the landscape in myself, and it allows me to see more clearly and make predictions for the future. I wave goodbye to the east, happy to see it's still transforming after its decline. There's a fair amount of construction and places for lease. More tech companies will settle, and more people will move in. The west is doing fine, it's distancing itself more and more from its industrial past. It's upmarket and prospering. I bet it will be for a long time based on its proximity to South Station and the Financial District. I chose Fort Point to understand the coexistence of two seemingly juxtaposed sides of a channel, and I've found how very interconnected they once were and always will be.

References:

Hayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1995. Print.

Spirn, Anne W. Language of Landscape. New Haven: Yale UP, 1998. Print.

Figure 2: Painted label on a building and BWC medallion.

Figure 2: Painted label on a building and BWC medallion.  Figure 4: Atlas of the City of Boston, Boston Proper and Back Bay, from Actual Surveys and Official Plans, 1917. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. G. W. Bromely & Co. 1917. Print.

Figure 4: Atlas of the City of Boston, Boston Proper and Back Bay, from Actual Surveys and Official Plans, 1917. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. G. W. Bromely & Co. 1917. Print. Figure 5: Russia building plaque. ©2014 Google · Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA · Imagery June 16, 2011

Figure 5: Russia building plaque. ©2014 Google · Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA · Imagery June 16, 2011 Figure 8: Sanborn Map Company. Boston Volume 4, 1950. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. Sanborn Map Company. 1950. Print.

Figure 8: Sanborn Map Company. Boston Volume 4, 1950. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. Sanborn Map Company. 1950. Print. Figure 9: Howe's Leather Company. ©2014 Google · Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA · Imagery June 22, 2011

Figure 9: Howe's Leather Company. ©2014 Google · Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA · Imagery June 22, 2011 Figure 15: No playground! ©2014 Google · Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA · Imagery June 22, 2011

Figure 15: No playground! ©2014 Google · Sanborn, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA · Imagery June 22, 2011 Figure 17: Sanborn Map Company. Boston Volume 1S, 1992. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. Sanborn Map Company. 1992. Print.

Figure 17: Sanborn Map Company. Boston Volume 1S, 1992. Map. In Boston, Massachusetts. Sanborn Map Company. 1992. Print.