Back Bay in Boston has always been revered as one of the “high-end” areas of Boston. Founded as an area for rich Bostonians to thrive separately from the poor, Back Bay has constantly struggled to maintain its identity, as there is increased urbanization of the areas around Boston. While Back Bay tried to stay isolated, ultimately the creation of the MBTA, the rise in population in Boston, and the invention of the car all prevented Back Bay from remaining the isolated, high-class area right outside of downtown Boston that it was intended to be. As cities opened up to suburbs, Back Bay ultimately opened up as well. But to this day, evidence of Back Bay fighting to maintain its character despite the changing culture of the city and urban environment can be observed.

The Origins of Back Bay: Boston’s need for land

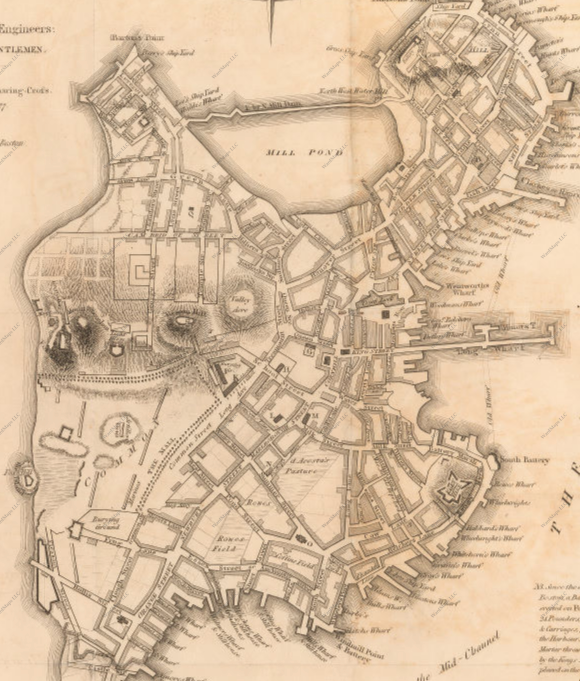

First, one must understand: how did Back Bay come to be? As Bostonians won the Revolutionary War and America became its own independent entity, Boston was already crowded. Figure 1 below from 1777 shows Boston as the center of most activity and land use in 1777:

Figure 1: Map of Boston in 1777. Note that most of the main city seems to be partitioned into different buildings, and there are no bridges to suburban areas. My site does not exist yet, but would be located on the left of the map. (Little, Brown & Co., Revolutionary War Maps of Boston 1777).

Figure 1: Map of Boston in 1777. Note that most of the main city seems to be partitioned into different buildings, and there are no bridges to suburban areas. My site does not exist yet, but would be located on the left of the map. (Little, Brown & Co., Revolutionary War Maps of Boston 1777).

By 1800, the Boston population was 25,000 (4.211 class website Timeline). The only areas on the map that do not appear to be fully developed are Beacon Hill and Boston Common. However, this changed in 1807 when Mill Pond was filled using the top of Beacon Hill (4.211 class website Timeline). Now, Boston was utilizing almost all of its land to build a downtown and have enough dwellings to accommodate its growing population. But would this be enough? Especially when there were limited forms of transportation between Boston and the suburbs, it was important that Boston remained central. Otherwise, people would not move into the city, and businesses could not flourish. One of the reasons Back Bay was constructed was simply to provide more land for the people of Boston.

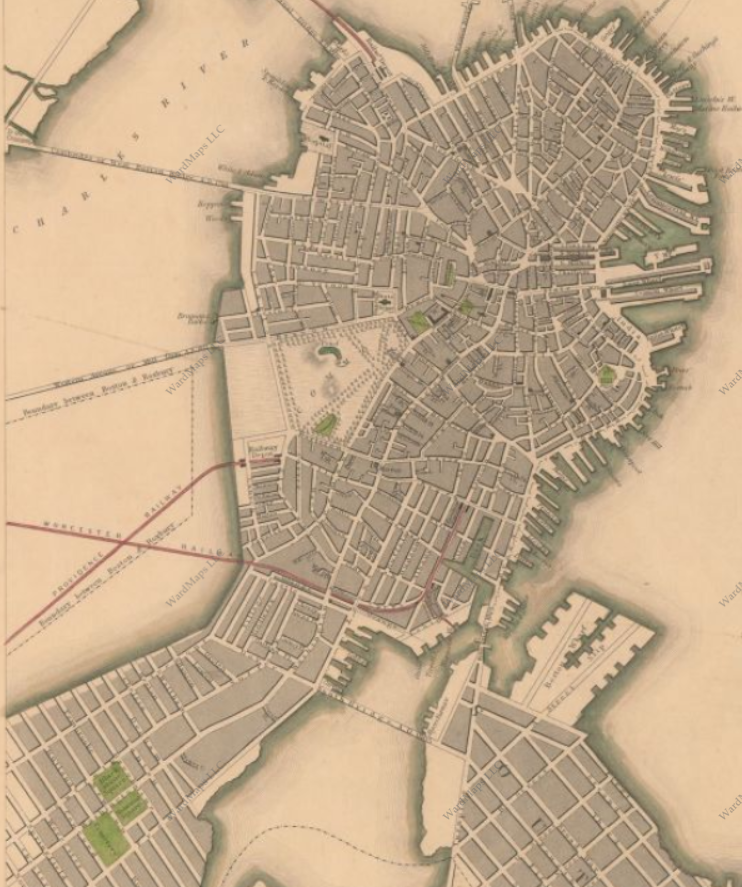

Additionally, in 1835, the first Boston Railroads opened (4.211 class website Timeline). Figure 2 below from 1842, shows in red the new railroads constructed:

Figure 2: Boston in 1841. Note the addition of the train tracks, but still the land in Back Bay has not been filled in to the left of Boston Common and above the train tracks crossing (Boynton, Boston 1841, 1841).

Figure 2: Boston in 1841. Note the addition of the train tracks, but still the land in Back Bay has not been filled in to the left of Boston Common and above the train tracks crossing (Boynton, Boston 1841, 1841).

Now, Boston had potential to become a center of industry, since railroads allowed mass transportation of supplies and people. In particular, the Worcester and Providence railroads were important to the building of Back Bay. The map shows these railroads cross in the area where Back Bay is located today. Having industry and people near where railroads cross is beneficial: they could easily transport goods from one railway to another, and people could use these railroads more effectively. This desire to utilize any means of transportation to help local businesses and factories was a driving factor in the creation of Back Bay.

Socially, the climate of Boston was changing as well. According to Jackson in Crabgrass Frontier, during this age of new technology and industrialization, there was “a new pattern of suburban affluence and center despair. The result was hailed as the inevitable outcome of a desirable segregation of commercial from residential areas and of the disadvantaged from the more comfortable” (Jackson, ch 2.1). This is evident in the early history of Boston. For example, Harrison Gray Otis, a wealthy Bostonian, purchased a large portion of Beacon Hill in 1795 (Jackson ch 2.1). His intent was to house other rich people. But Beacon Hill is small, and Boston’s population was expanding rapidly. This was coupled with the “tendency for a privileged few to move away from close proximity to their businesses” (Jackson, ch 5.7). With the cultural shift of people desiring a separation of rich and poor, the introduction of railroads crossing in the Charles River, and not enough space in Boston, something had to be done. The solution to these problems was to expand Boston. Thus, Back Bay was filled in.

Social Tensions in Back Bay: Wealthy homes and poor railroad workers

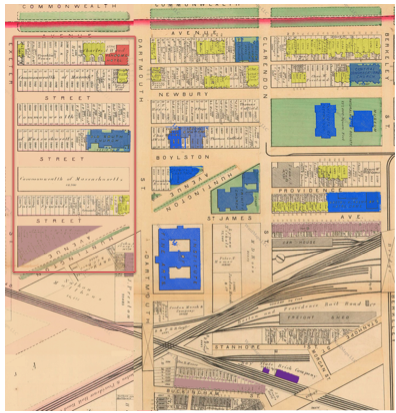

From the very beginning of its existence, Back Bay has felt many tensions between the need to accommodate for a changing social climate in Boston and the desire to keep the area “high class”. The 1874 map below (figure 3) shows Churches (light blue), academic institutions (dark blue), homes (yellow), small homes/apartments (brown), and the railroad (grey):

Figure 3: Map of my site (outlined in red) and the surrounding area in 1874. Note the train tracks crossing below St. James St, and the large proportion of institutions. At this point, Copley Square and Back Bay had minimal infrastructure (G.M. Hopkins and Co., Boston 1874, 1874).

Figure 3: Map of my site (outlined in red) and the surrounding area in 1874. Note the train tracks crossing below St. James St, and the large proportion of institutions. At this point, Copley Square and Back Bay had minimal infrastructure (G.M. Hopkins and Co., Boston 1874, 1874). In a broader sense, Back Bay used to be water. Perhaps the water still wants to be there. Back Bay is man made to defy the natural purpose of the land, but the land itself now impacts the man-made concrete. Poor drainage and the natural traffic of a city combined create cracks in the pavement that will eventually make it unusable. The terrain also has significant impacts on the wind patterns in Back Bay.

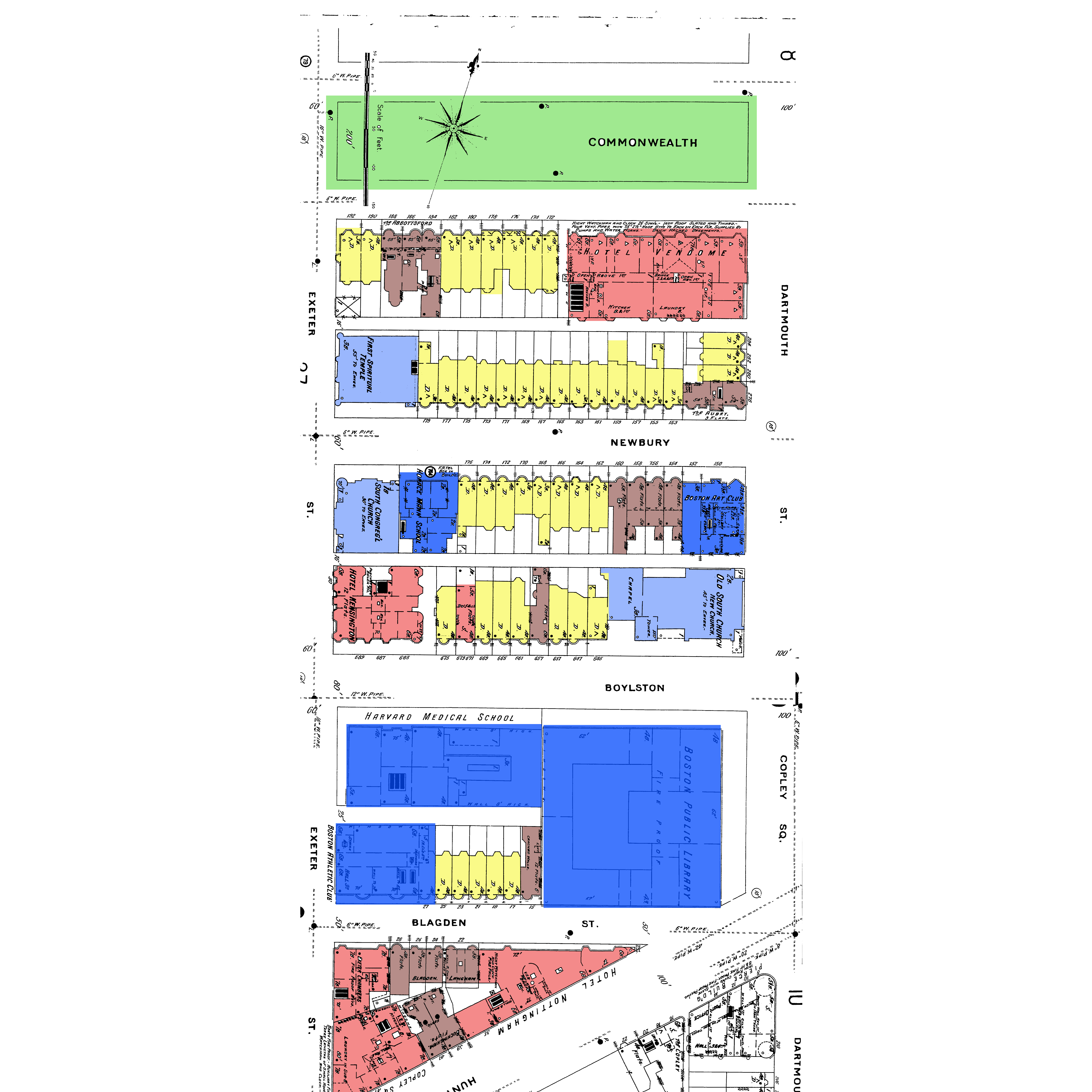

From this general map, it is clear that Back Bay is trying to be an isolated community far away from work by having its own Churches, homes, and institutions. By doing this, they could separate themselves from the less wealthy and from industry. My site (outlined in red), on a smaller scale, exhibits these changes. Since it a slice through Back Bay, the overall changes can be seen in my site. By 1897, it is clear that Back Bay is developing as its own residential entity. Figure 4 shows the divide between the residential and institutional areas above Blagden St and the railroad, while below it there are an increasing number of flats and businesses (such as laundry):

Figure 4: Map of Boston in 1898. Note the increase in residential homes and institutions. From this, it appears Back Bay has become its own community outside of downtown Boston (Sanborn maps, 1898, Volume 2).

Figure 4: Map of Boston in 1898. Note the increase in residential homes and institutions. From this, it appears Back Bay has become its own community outside of downtown Boston (Sanborn maps, 1898, Volume 2).

The changes in my site over 25 years shows that Back Bay is becoming its own “mini-suburb” in the heart of Boston. With the addition of the Boston Public Library, new institutions moved to this area. Harvard Medical School located itself right next door to the library, and the Horace Mann School and the Boston Art Club moved to Newbury Street. These institutions (including MIT a few blocks over) made Back Bay and Copley Square central areas of higher level art and education that were not accessible to lower classes at the time. The museum of Fine Arts was moved to this area, showing Boston’s metropolitan shift (4.211 class website Timeline). These academic centers were appreciated by the wealthier class, so the introduction of so many institutions to the Back Bay during this time further isolates it from the less wealthy areas of Boston. This follows with the initial plan of Back Bay.

According to Jackson, the wealthier urban group had three options in the late nineteenth century: “to remain in a private dwelling within the city, to move to an elegant apartment house, or to relocate on the growing edges” (Jackson, ch 5.2). As cities grew, residential areas were closer to commercial areas, which was undesirable because it was loud and busy. In the Back Bay, there were many attempts early on to build single-family dwellings or nice apartments in order to avoid relocating to the growing edges (and thus staying close to the heart of Boston). This can be seen in the maps of increasing years: more yellow (single family homes) takes the place of other industries and apartments in areas on my site. In a way, these homeowners were creating suburbs within the city: they were near the bustle of downtown, but could enjoy having large homes in a quieter area. This could be the cause of all the Protestant Churches. It appears there is an increase in Churches across Back Bay, particularly those that are not Catholic. At this time in Boston, nationalities that were typically Catholic were poorer, and most homeowners in the Back Bay were of English decent (see figure 7 below). The rise of separate Protestant Churches in Back Bay shows the isolation these homeowners wanted from the rest of Boston, while still being close to the city center. But would this structure be sustainable over time?

Transportation Revolution in the Back Bay: No more isolation!

The first Model T in 1908 as well as the development of the MBTA system had a profound impact on how Back Bay developed in the 20th century (4.211 class site Timeline). Up until the early 20th century, it was difficult for regular commuters to easily travel in and out of Boston, thus allowing Back Bay to maintain its isolation. The first impact that the changing transportation systems had was the diminishing importance of the railroad. Over time, the railroads from Worcester to Boston (and other cities) became less efficient than driving or taking the MBTA. This helped the Back Bay maintain its wealthy character because it removed the railroad industry and the less wealthy people associated with it. According to Jackson, “Typically [the railroad workers] lived in either servant’s quarters within the estate grounds or in modest dwellings that surrounded the railroad stations” (Jackson, ch 5.6). When railroads became less important, these people could not keep their jobs or stay located near Back Bay and the railroad. Figure 5 below from 1917 shows the elimination of multiple-family dwellings as a result of the changing modes of transportation:

Figure 5: Map of Back Bay in 1917. Note That now Back Bay is primarily single family residences and institutions (Bromley Boston 1917, 1917 volume 2).

Figure 5: Map of Back Bay in 1917. Note That now Back Bay is primarily single family residences and institutions (Bromley Boston 1917, 1917 volume 2).

However, the elimination of multiple-family dwellings and poor housing would not be a lasting trend. By 1910, “In Massachusetts alone, 211 ‘towns’ were served by street railways” (Jackson, ch 6.5). Now, Back Bay could no longer isolate itself completely: the Copley T station was built! Many changes on my site between 1917 and 1937—a mere 20 year period—show how mass transportation affected the isolated Back Bay (see figure 6 below).

Figure 6: Back Bay in 1937. In just 20 years, Back Bay transformed from primarily residential to largely commercial land uses. This shift is due to the opening of Boston from public transportation and automobiles (Sanborn, Boston 1937, 1937 volume 2).

Figure 6: Back Bay in 1937. In just 20 years, Back Bay transformed from primarily residential to largely commercial land uses. This shift is due to the opening of Boston from public transportation and automobiles (Sanborn, Boston 1937, 1937 volume 2).

As Figure 6 illustrates, the spiritual temple on Exeter and Newbury became a theatre, indicating that perhaps Churches combined elsewhere since other areas of Boston were more accessible. Many hotels are constructed below Blagden Street and on Commonwealth Ave. These changes show that Back Bay is no longer isolated to a few wealthy people: people can take the T to a move theatre, or people out of town can stay at a hotel. Back Bay was slowly opening up to cater to the general public, and not just a few wealthy landowners who want autonomy from the city. Once again, the social climate was changing in order to make Boston more accessible from the growing suburbs. As Jackson states, “better streetcar lines to the suburb would … combat all social ills by decentralizing the inner city population” (Jackson, ch 7.1). Slowly, the isolated “suburb” of Back Bay was being opened up to the rest of the city, and it became a less necessary place for wealthy Bostonians to live.

Another reason for the changing land use was a social change resulting from the invention of the Model T. By 1927, according to Jackson, “the ownership of an automobile had reached the point of being an essential part of normal middle-class living” (Jackson, ch 9.2). A large portion of the population could now easily travel to Boston from the suburbs, and the desire to live in a nice house close to downtown Boston became less important (after all, it was loud). The center of the city was decentralizing. In Back Bay, there is a stark decrease in single family homes and a large increase in shops, apartments, and hotels in the 1937 map, indicating Back Bay was no longer a primarily residential area. In this time, Back Bay became a center of shopping because of its accessibility and the changing attitudes of the suburban population. Now, it was acceptable for people outside of the city to visit the city.

Cultural Changes in the Back Bay: The quiet suburbs vs. the noisy downtown and the Great Depression

The change of land in Back Bay being used as homes to used as shops represents a societal change: people no longer wanted to be near the congested downtown area. . This is evident in the previous maps showing less residential area. When Back Bay was created, it was nearly impossible for people in the suburbs to easily travel into the city. This is what made Back Bay such an attractive place to live: it could be its own isolated “suburb” that was close to the excitement of downtown. But in the 1920s, “undeveloped land on the metropolitan fringes became prime residential real estate” (Jackson, ch 10.2). The city was looked at as loud and dirty. Back Bay became a place to visit, not a place to live. Undeveloped land was what people wanted: a quiet home and large backyard. And thus, storefronts appear in place of homes.

However, Back Bay still maintained its level of higher-class residency and shops. This is evident from comparing Bromley maps from 1917 and 1938:

a.

b.

Figure 7: Comparison of Back Bay ownership from 1917 (a) and 1938 (b). Note that ownership changes, but the nationality of the last names does not. (Bromley Boston 1917, Boston 1938).

Figure 7: Comparison of Back Bay ownership from 1917 (a) and 1938 (b). Note that ownership changes, but the nationality of the last names does not. (Bromley Boston 1917, Boston 1938).

Many of the landowners change, and so does the land use. However, by looking at the names of the landowners, they all still seem to be English last names. This shows that while the area was changing, it was not becoming more diverse, and the typically upper-class people still owned the property (by this point, there was still significant racial segregation in Boston). However, the economy was suffering due to the Great Depression and it is unlikely many people could afford to comfortably live in a large home. Thus, storefronts with apartments on top could have been created in order for homeowners to save money and hopefully make income. Nevertheless, Back Bay still isolates itself from many of the problems that less wealthy Americans faced at the time: the rich still remained rich, as evidenced from the landowners. Despite the Great Depression, landowners in Back Bay still retained their land, or sold it to those likely of similar status. Thus, for the first time, Back Bay is not a product of the social changes in the rest of America due to unemployment.

Yet the overall transition from residential to commercial continues through the 1940s and 1950s. Figure 8 below shows my site in 1951:

Figure 8: Map of Boston in 1951. The land use has primarily stayed the same since 1938, but there are a few more apartments, indicating the area is no longer just wealthy single-family homeowners. (Sanborn, Boston 1951, 1951).

Figure 8: Map of Boston in 1951. The land use has primarily stayed the same since 1938, but there are a few more apartments, indicating the area is no longer just wealthy single-family homeowners. (Sanborn, Boston 1951, 1951).

The site has primarily stayed the same, with a few more apartments added. In this period of time, America saw the end of the depression and the beginning and end of World War II. Yet Back Bay’s land use does not experience many changes. The GI Bill was passed in 1944, so more and more people move to the suburbs (4.211 class site Timeline). This further reinforces Back Bay as a shopping district, and not a living district with single family homes. The population of Boston peaks in 1950, but there appears to be no increase in housing in Back Bay. Yet the Boston Public Library, Boston University, and other institutions are still there. Back Bay still remained an educational and shopping hub for people in Boston, but there appears to be no hope of it becoming an isolated, house-heavy area of Boston.

Modern-Day Back Bay: A commuter hub

Not much changed in Back Bay maps from the early 1950s until the 1990s. However, Figure 2 (from 1992) shows a stark increase in the amount of parking lots in Back Bay (dark grey):

Figure 9: 1992 map of Boston. Parking garages have been added to accommodate the high traffic into downtown Boston and Back Bay (Sanborn, Boston 1992, 1992).

Figure 9: 1992 map of Boston. Parking garages have been added to accommodate the high traffic into downtown Boston and Back Bay (Sanborn, Boston 1992, 1992).

By the 1980s, having a car was the norm for most Americans. According to Jackson, “the best symbol of individual success and identity was a sleek, air-conditioned, high-powered, personal statement on wheels” (Jackson, ch 14.1). The construction of Boston’s Central Artery in 1950 was designed to allow people to get to Downtown Boston easily (4.211 class website Timeline). Cars allowed students and parents, employed and unemployed, old and young, to travel to Boston. Just on my site, two parking areas emerged to accommodate people visiting the area. My site became a high traffic area for cars, students, and people visiting Back Bay and Boston because of its close proximity to the large highways being constructed. The social climate has completely transformed since the 1840’s: now, Boston was supposed to be accessible to people of the suburbs, not isolated.

There are almost no religious institutions or academic institutions on my site by 1992. The Old South Church is the only Church that remains—the rest have been sold to become shops. Academic institutions besides the Boston Public Library moved away from Copley Square. This is what Jackson calls “The loss of community in Metropolitan areas”. Back Bay could not avoid this. Back Bay was created with strong feelings of separating the rich and the poor, and creating an isolated community with churches and academic institutions that the wealthy could enjoy. Back Bay, by 1992, no longer had this identity. A century ago, “[the city] possessed a significant sense of local pride and spirit as a result of struggles with other cities for canals, railroads, factories, and state institutions” (Jackson, ch 15.1). By 1992, Back Bay had no railroads, almost no institutions, and no factories. An area that tried to avoid the effects of suburbanization, and tried to stay isolated, ultimately could not remain this way forever. Ultimately, Back Bay conformed to the changing social climate of Boston and its suburbs.

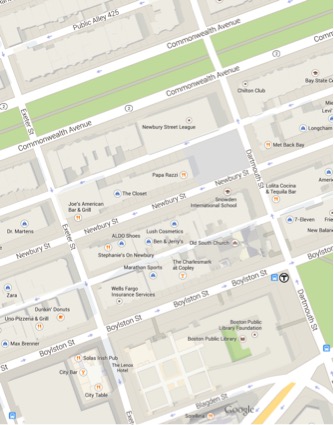

While Newbury Street and Back Bay have become known for their shopping, they still manage to differ from the typical mall. According to Jackson, “During the 1970s, a new phenomenon—the super regional mall—added a more elaborate twist to suburban shopping” (Jackson, ch 14.7). Indoor malls, with many stores, became the normal place for suburban families to shop. Yet Newbury Street remains outdoors, and has many boutiques and more expensive shopping areas. Throughout history, and even now, establishments in the Back Bay have continued to differentiate themselves from the middle-class establishments. Figure 10 below is a modern-day map of my site:

Figure 10: Present-day map of my site. The boundaries are Exeter and Dartmouth Streets, and Commonwealth Ave and Blagden Street. (Google Maps, 2015).

Figure 10: Present-day map of my site. The boundaries are Exeter and Dartmouth Streets, and Commonwealth Ave and Blagden Street. (Google Maps, 2015).

Many of the buildings are the same as the originals, but their land uses are drastically different. Commonwealth Ave hosts many apartments, Newbury Street has primarily shops and restaurants, and Boylston Street has many “necessity” stores and businesses. Only the Old South Church and the Boston Public Library remain as historic areas. The people who once inhabited Back Bay have moved instead to the less densely populated suburbs. Urbanization has led to Newbury Street no longer being an area inhabited by primarily wealthy people: now it is accessible to students. The Hynes Convention Center MBTA stop helps make Back Bay an easily accessible place to shop, walk, and explore.

Back Bay, to this day, maintains the same flavor as it did when it was created in the late 1800s. It is still known as the high-end area of Boston. The shops on Newbury Street are expensive. While the growth of public transportation, the movement of wealthier families out of Boston, the Great Depression, wars, and the decentralization of Boston fundamentally changed the land uses of Back Bay, but could not eliminate the distinctive “high-class” culture. As analyzed in Crabgrass Frontier, city centers became more commercial, and people moved to the suburbs. Cars changed the way in which people interacted with their cities. Back Bay remains an epitome district that has been opened up to the general public. However, it represents the struggles that Boston faced in keeping a high-class residential area, and ultimately the original purpose of Back Bay was not preserved. Through Back Bay, one can see the changes that occurred in the suburbs of Boston and how it affected the inner-city dwellings. If anything, this shows that a neighborhood is constantly changing: a city is not static, and the needs of the people decide how a neighborhood develops.

Image Sources:

[1] 1777 Siege of Boston [map]. 1777 “Revolutionary War Maps of Boston: Little, Brown and Co.”. Digital. Wardmaps Antique Maps.

[2] Boston 1841 [map]. 1841 “Boston Back Bay: Boynton”. Digital. Wardmaps Antique Maps. < http://www.wardmaps.com/browse.php?cont=1&count=1&state=1&city=1 > (6 April 2015).

[3] Boston, Massachusetts [map]. 1874 “Boston Back Bay: G.M. Hopkins and Co.”. Digital. Wardmaps Antique Maps < http://www.wardmaps.com/browse.php?cont=1&count=1&state=1&city=1>(6 April 2015).

[4] Boston, Massachusetts [map]. 1898. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1898". Digital Sanborn Maps 1867-1970. (7 Apr 2015).

[5] Bromley, G.W. 1917 Atlas of Boston.1917, “Atlas of the City of Boston: Boston Proper and Back Bay,” Massachusetts Real Estate Atlas Digitization Project. < http://www.mass.gov/anf/research-and-tech/oversight-agencies/lib/massachusetts-real-estate-atlases.html> (6 Apr 2015).

[6] Boston, Massachusetts [map]. 1937. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1937". Digital Sanborn Maps 1867-1970. (8 Apr 2015).

[7a] Bromley, G.W. 1917 Atlas of Boston.1917, “Atlas of the City of Boston: Boston Proper and Back Bay,” Massachusetts Real Estate Atlas Digitization Project. < http://www.mass.gov/anf/research-and-tech/oversight-agencies/lib/massachusetts-real-estate-atlases.html> (6 Apr 2015).

[7b] Bromley, G.W. 1938 Atlas of Boston.1938, “Atlas of the City of Boston: Boston Proper and Back Bay,” Massachusetts Real Estate Atlas Digitization Project. < http://www.mass.gov/anf/research-and-tech/oversight-agencies/lib/massachusetts-real-estate-atlases.html> (6 Apr 2015).

[8] Boston, Massachusetts [map]. 1951. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1951". Digital Sanborn Maps 1867-1970. (8 Apr 2015).

[9] Boston, Massachusetts [map]. 1992. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1992".

[10] Google Maps (2014). [Back Bay, Boston,MA] [Street Map]. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/maps/@42.3507758,-71.0785496,18z

Works Cited

[1] Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985). Kindle File.

[2] 4.211 Class website timeline, 2015.