Natural processes constantly shape the man-made buildings, streets, and land in cities. The Back Bay area of Boston, which is entirely man-made, is continuously altered due to the land flatness, high wind speeds, accumulation of water, and light. These natural processes and phenomena have helped determine the uses of the land in Back Bay, as well as emphasized some of the larger problems of the design of Boston as a whole. High winds make walking down Boylston Street miserable, but bright sunlight on Newbury Street makes it a lovely place to shop. Natural processes and human creations are constantly fighting one another, such as in the Emerald Necklace (which is close to my site in Back Bay). But when humans understand natural processes and how to utilize them rather than ignore them, then a functional city can be created.

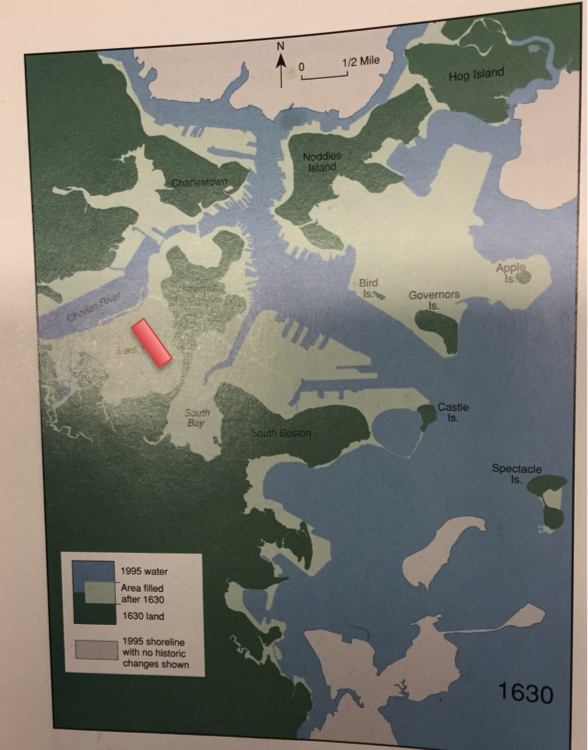

Back Bay itself is a manmade creation, but it is continuously shaped by natural processes. Figure 1, from Mapping Boston, shows when Back Bay was filled in, with my approximate site marked:

Figure 1: Map of Boston from Mapping Boston (Krieger and Cobb, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999). The light green area was filled in land after 1630, while the dark green area is land that existed in 1630. My site approximate site (which did not exist in 1630), is marked in red.

Figure 1: Map of Boston from Mapping Boston (Krieger and Cobb, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999). The light green area was filled in land after 1630, while the dark green area is land that existed in 1630. My site approximate site (which did not exist in 1630), is marked in red.

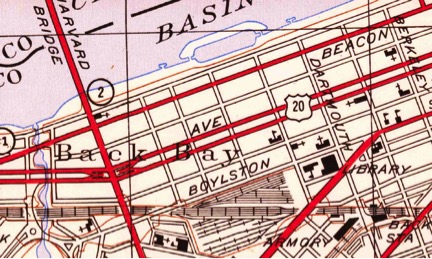

Back Bay was filled in over a long span of time over a century ago, and many of its features today indicate that it an artificial piece of land. Over many years, water from the Charles was covered with dirt. This has impacted the terrain of the Back Bay area. Figure 2 shows a USGS topographic map of the area (my site is between Dartmouth St and Exeter St, which is one parallel street to the left of Dartmouth):

Figure 2: USGS topographic map of Back Bay (Boston: USGS Topographic Survey, 1954). The site described in this paper is from Commonwealth Avenue to Boylston Street and from Exeter Street to Dartmouth Street. This land is all enclosed in a 10-foot elevation level.

Figure 2: USGS topographic map of Back Bay (Boston: USGS Topographic Survey, 1954). The site described in this paper is from Commonwealth Avenue to Boylston Street and from Exeter Street to Dartmouth Street. This land is all enclosed in a 10-foot elevation level.

Figure 2 shows that Back Bay is almost entirely the same elevation, and is very close to sea level (about 10-20 feet elevated). As Global Warming becomes a risk to society, this could potentially pose problems with elevated sea levels. Even some observations near and on my site show poor draining: much of the water is stagnant because it cannot flow downstream to the Charles. Figure 3 shows a large puddle as a result of minimal sloped terrain in the Back Bay area.

Figure 3: giant puddle on Mass Ave (about 0.3 miles from my site) showing little drainage due to the flatness of the land.

Figure 3: giant puddle on Mass Ave (about 0.3 miles from my site) showing little drainage due to the flatness of the land.  Figure 4: Photograph taken of the intersection between Exeter St and Commonwealth Ave. Visible cracks are apparent on street corners where there was snow accumulation and high pedestrian and car traffic.

Figure 4: Photograph taken of the intersection between Exeter St and Commonwealth Ave. Visible cracks are apparent on street corners where there was snow accumulation and high pedestrian and car traffic.

Especially with winters such as Winter 2015, the accumulation of water causes more pedestrian traffic and a generally messy city. In extreme cases, this could cause flooding. Flooding is harmful to the basements of many houses on my site, as well as creates cracks in the pavement (Elkins). According to Elkins, this type of cracking is called fatigue cracking, and is caused by overuse and/or “bad drainage, which allowed water to permeate the surface layer” (Elkins 29). I think both of these are reasons for pavement cracking in Back Bay. In the street corners that were visibly covered with snow in March, visible cracks are apparent. Figure 4 shows an intersection similar to that of Figure 3 with extreme cracking.

Back Bay is man made to cover the natural purpose of the land, but the land itself now impacts the man-made concrete. Poor drainage and the natural traffic of a city combined create cracks in the pavement that will eventually make it unusable. The low temperatures expected in the winter also cause low-temperature cracks, according to Elkins, which can be seen through the long crack in the middle of Figure 4. The low temperature of Boston winters combined with the low terrain and heavy traffic make it difficult to maintain uncracked pavement on my site. This is an example of nature and humans acting against one another, and the results are detrimental to city drivers and cause money to be spent on fixing the cracks. The terrain also has significant impacts on the wind patterns in Back Bay.

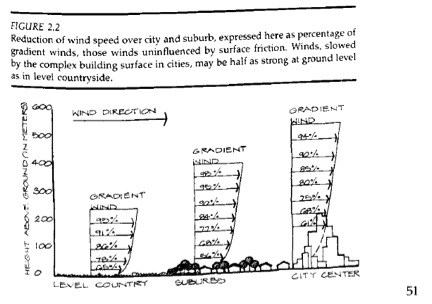

The wind patterns along Boylston Street are particularly strong compared to parallel streets due to many large buildings, such as the Prudential Center and the Lenox Hotel. According to Spirn, “numerous office towers downtown… catch wind and send it swirling down to the street” (Spirn 28). These buildings, coupled with the relative narrowness of Boylston Street, cause strong winds to travel along Boylston Street. Figure 5 is a figure from The Granite Garden showing the effects of different sized buildings on wind speed.

Figure 5: Spirn’s representation of wind reduction due to large buildings. On Boylston Street, one side has many tall buildings, while the other side (separated by just two lanes of traffic) has much shorter buildings. This creates complex wind patterns (Spirn, The Granite Garden).

Figure 5: Spirn’s representation of wind reduction due to large buildings. On Boylston Street, one side has many tall buildings, while the other side (separated by just two lanes of traffic) has much shorter buildings. This creates complex wind patterns (Spirn, The Granite Garden).

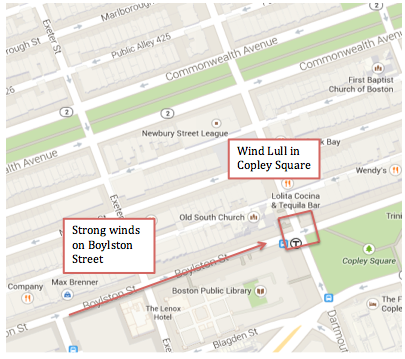

The Prudential Center used to be an outdoor mall, but the winds were so strong it had to be turned into an indoor mall (Spirn, conversation). Spirn asserts in The Granite Garden that wind speeds and lulls are “a product of the interaction of changing regional wind speeds and directions with surface topography, the aerodynamic shapes of nearby buildings, the size and shape of the space surrounding them, and the form of the city upwind” (Spirn 52). Boylston Street is a perfect representation of these phenomena: it is incredibly windy, but there is a lull at Copley Square. A Google Map image (Figure 6) shows the wind direction on Boylston street, and the area of the lull.

I revisited the site for the revision (May 11, 2015), and noticed the same wind speed and direction. On this day, the wind was 6 MPH east off the shore. This is about consistent with my observations: the wind is still approximately eastward in direction, but it picks up speed until it is dispersed in Copley Square. Because of the grid-like shape of the streets, the wind is tunneled down them. Since the streets in Back Bay are generally narrow, the wind is funneled through them and becomes more intense.

Figure 6: Google Maps view of Boylston Street wind direction and the lull of wind present in Copley Square (Google Maps, 2015). This contrast makes it painful to walk down Boylston Street, but pleasant to stand on the intersection of Boylston Street and Dartmouth Street.

Figure 6: Google Maps view of Boylston Street wind direction and the lull of wind present in Copley Square (Google Maps, 2015). This contrast makes it painful to walk down Boylston Street, but pleasant to stand on the intersection of Boylston Street and Dartmouth Street.

Spirn asserts that “calms persist at the bottoms of deep courtyards and other confined spaces” (Spirn 51), which can explain why there is a wind lull in Copley Square. The creation of Copley Square, a small park in the middle of a windy area, helps minimize the wind that has built up along Boylston Street. This is a good location for reduced wind speeds because the Boston Public Library and Copley T Station attract many people. It also represents an example for which the city works in order to accommodate its natural processes. Whether by accident or on purpose, the city adding some green space helps alleviate wind problems. Sometimes, nature can benefit a city if used properly.

The flatness of Back Bay also contributes to these strong winds (refer to Figure 2). Back Bay is almost completely flat until Boylston Street. Without hills to create friction to slow down wind, and due to the straight nature of the road, there is nothing to stop winds that are parallel to the Charles from gusting down Boylston Street. This has affected the way in which buildings were designed on Boylston St. The Prudential Center was made into an indoor mall in order to attract consumers who otherwise would not want to shop outside in the wind. I would not be surprised to see tunnels or indoor overpasses built in the future as I observe Boylston Street become more consumer oriented. The Prudential Center is a way in which the city has adapted to work with the natural processes that shape it.

There are greater implications of wind patterns on city development than just on my site. As buildings have the ability to be built taller, and more people live in cities, the need for large skyscrapers has increased. The removal of many of the brownstones on my site for larger consumer buildings is proof of this. Yet the wind patterns they can create, such as those by the Prudential Center, make it difficult for people to use the areas around them. Because of strong winds, people did not want to use an outdoor mall. If people do not go to Boylston Street to shop, businesses do not make money and people do not enjoy walking down it. By neglecting to analyze how wind could shape a street, a usable street can become unusable. As more and more tall buildings are constructed, it is imperative to keep wind patterns in mind. Through Copley Square and the Prudential Center, one can see that it is possible to work with the wind instead of perpetuate it.

The green strip of land on my site, called the “Commonwealth Ave Mall” is another man-made “natural” area. The mall consists of a green strip of land with a walkway in the middle and trees planted in straight lines, and is part of the Emerald Necklace (Spirn 172). Like the Fens, it is a man-made park. However, much different than the Fens, the Commonwealth Ave Mall is thinner, flattened in the middle of a busy road, and constantly altered directly by humans. This is evident by a lack of natural wildlife (plants and animals) on the mall. Trees do not grow in perfectly straight lines on their own. Figure 7 shows an image of the mall between Dartmouth and Exeter Streets.

Figure 7: The Commonwealth Avenue Mall. This green strip of land is lined with a row of trees on either side and has had limited success as a part of the Emerald Necklace.

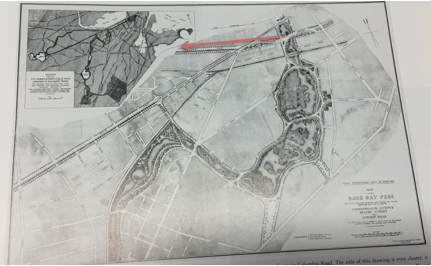

Figure 7: The Commonwealth Avenue Mall. This green strip of land is lined with a row of trees on either side and has had limited success as a part of the Emerald Necklace. As stated in The Granite Garden, “human function and fashion are often more influential than natural processes in determining the location and arrangement of plants” (Spirn 172). The Commonwealth Ave Mall represents human impact on land that was supposed to be natural. The Emerald Necklace was a construct to help with drainage in Boston, but now its purpose has been muddled. The Commonwealth Ave Mall is no longer linked to the Necklace: there is an expressway that blocks it from the Fens. Figure 8 (from Mapping Boston), shows the Emerald Necklace with Commonwealth Ave labeled in red.

Figure 8: The intact Emerald Necklace from Mapping Boston (Krieger and Cobb, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999) with a red arrow indicating the direction and length of the Commonwealth Ave mall. The Commonwealth Ave mall is no longer directly connected to the rest of the Emerald Necklace due to highway infrastructure.

Figure 8: The intact Emerald Necklace from Mapping Boston (Krieger and Cobb, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999) with a red arrow indicating the direction and length of the Commonwealth Ave mall. The Commonwealth Ave mall is no longer directly connected to the rest of the Emerald Necklace due to highway infrastructure.

Additionally, according to Spirn, the “beloved Elm trees on Commonwealth Avenue Mall were nearly killed by too much attention than too little” (Spirn 173). Apparently, hundreds of thousands of dollars were spent on an irrigation system for the trees that instead caused root damage. The trees did not need help: the flat and low nature of Back Bay facilitated the health of the trees. This is a great example of people trying to preserve nature without understanding it.

While the Commonwealth Avenue Mall is man-made, it is undeniable that there are natural phenomena that affect the Commonwealth Ave Mall. The rows of trees naturally lean to the South (see figure 7) in order to optimize the amount of sunlight. Many trees are tall and have thick bases, indicating they are healthy. However, most of the trees that are on the left side of the road and not south facing are much thinner and less healthy. Perhaps they had to be replanted. This statement was further justified when I revisited the site after the snow melted. Figure 9 shows a stump of a deceased tree, indicating it is there to help protect trees from the Dutch Elm Disease by sharing nutrients for pest control.

Figure 9: deceased stump that still exists in order to share nutrients with surrounding trees.

Figure 9: deceased stump that still exists in order to share nutrients with surrounding trees.

The Commonwealth Avenue Mall is a small natural section of the city that represents a much bigger problem: how to preserve wildlife in a city. The mall is between two lanes of a high traffic road, leading to toxic air for trees and any wildlife. The mall itself is no longer connected to other natural land. It almost seems that the mall has become a nice view for the residents of Commonwealth Ave, but not a green space for wildlife. In a larger sense, it is a failure of society to understand this wildlife. Because people have tried so hard to preserve the mall, they have wasted thousands of dollars and killed many trees. If from the beginning, the mall had been allowed to flourish like the Back Bay Fens, it could be an oasis for wildlife and trees could have a better chance of survival. Trying to create nature in a city, and trying to preserve natural habitats in an unnatural setting proves to be difficult.

One aspect of the flat land that enhances my site is the amount of sunlight that Commonwealth Ave, Newbury St, Boylston St, and their street corners receive. Figure 10 was taken on Newbury St between Exeter St and Dartmouth St, which indicates the brightness of a typical day on the street.

Figure 10: Photograph of Newbury St facing Dartmouth St. The left side of the image is north-facing. Trees are bowed inwards to receive the strong sunlight that shines down the street.

Figure 10: Photograph of Newbury St facing Dartmouth St. The left side of the image is north-facing. Trees are bowed inwards to receive the strong sunlight that shines down the street.

Figure 10 shows the lack of shadows on the street, indicating strong sunlight running down its length. The trees are also bowed into the middle of the street in order to obtain the strong sunlight shining. They are leaning towards the north, because the center of the street has much more sun than the shade from the buildings. This indicates that the street itself receives a substantial amount of sunlight. The brownstone buildings are also only a few stories high, so they do not block a significant amount of sunlight. Because of this, it is pleasant to walk along my site on Newbury St. On a Monday afternoon in the spring, the streets are packed with people window shopping or eating at one of the many restaurants that line the streets. The sunlight helps make Newbury St a desirable place to shop or eat outdoors.

Boylston St, in contrast, is much more shaded. It feels much more like an alley due to shadowing from the larger buildings that have moved in, such as the AT&T building on my site. However, the street intersections are still extremely bright, making them good locations for landmarks and T stops. The intersection of Dartmouth Street and Boylston St is where Copley Square begins, and it is extremely bright. The Old South Church and Boston Public Library are pictured in Figure 11.

Figure 11a: the Old South Church taken on Boylston St facing Exeter St.

Figure 11a: the Old South Church taken on Boylston St facing Exeter St.  Figure 11b: ) the Boston Public Library taken from the intersection of Boylston St and Exeter St. Both images show how bright this intersection is.

Figure 11b: ) the Boston Public Library taken from the intersection of Boylston St and Exeter St. Both images show how bright this intersection is. Because Copley Square is a public space, it provides a buffer between larger buildings and the street corner. This means there is less shade from these tall buildings. This symbolically makes Copley Square a central area. Boston was built to be the “city on the hill”, and the brightness when one enters Copley Square makes it feel like a beacon. In this case, the natural sunlight and the reduction in tall buildings of the area make it an inviting place. When nature and man-made artifacts work together, there can be beautiful outcomes.

The site discussed in this paper represents a broader issue that pervades throughout cities: how does one balance nature with new infrastructure? Should nature be preserved, left alone, or destroyed in cities? The Commonwealth Ave Mall represents the harm that people can do to nature, even when intentions are good. The mall was part of a greater project to utilize greenery as a walkway and for drainage, but now the mall has been separated from this project. Many trees were destroyed and money spent on people trying to preserve this seemingly unnatural natural life. When people create large buildings, they can unintentionally cause complex wind patterns. In a broader context, not understanding the natural environment causes the natural environment and man-made buildings and land to conflict.

As cities grow, these issues become more and more important to solve. Buildings can become (and often need to be) larger and space is limited in cities. The Back Bay area was created to make more land for the city to expand. Yet as evidenced from the success of the Fens and most of the Emerald Necklace, having natural parks and land in a city is also valued. Perhaps the smaller parks, like Copley Square, will prevail in the end: they are a small oasis in a commercial area. The bright sunlight makes it a place that is desirable to visit, and the clear lull in winds is pleasant. As cities grow, it is important to utilize the space remaining to make the experience for its inhabitants more positive. If this is done, and nature is understood rather than fought against, then a city can flourish.

Images Cited:

All photographs taken by Gabrielle Ledoux unless otherwise noted.

Figure 1, 7: Krieger, Alex, and David Cobb, eds. Mapping Boston. Cambridge, Mass.: [MIT], 1999. Print.

Figure 2: U.S. Geological Survey, Topographic Survey of Boston South. 1954.

Figure 3: Leonard, Anna. 2015.

Figure 5: Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic, 1984. Print.

Figure 6: Google Maps. 2015. [Back Bay, Boston][Street Map]. Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/maps/@42.3508756,-71.0792171,16z

Works Cited

Elkins, James. How To Use Your Eyes. New York: Routledge, 2000. Print.

Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic, 1984. Print.

Spirn, Anne Whiston. Conversations from Class (February 2015- May 2015).