Back Bay today is an interesting agglomeration of residential, commercial, luxury stores, and historic buildings. But what made it this way today, and where is it going? The question is hard to answer, and there are many conflicting architectural changes to the areas. Some buildings have been preserved despite their changing uses, while others have been demolished or overtaken by modern buildings. The Old South Church, The Commonwealth Ave Mall, and the Boston Public Library all represent points in history that define Back Bay. But as commercialism becomes more important to the area, new buildings could overtake the old ones, and Back Bay could become a modernized center of Boston. But what can we expect to see from Back Bay in 10 years, 50 years, 100 years?

1. Building Reuse Through Time

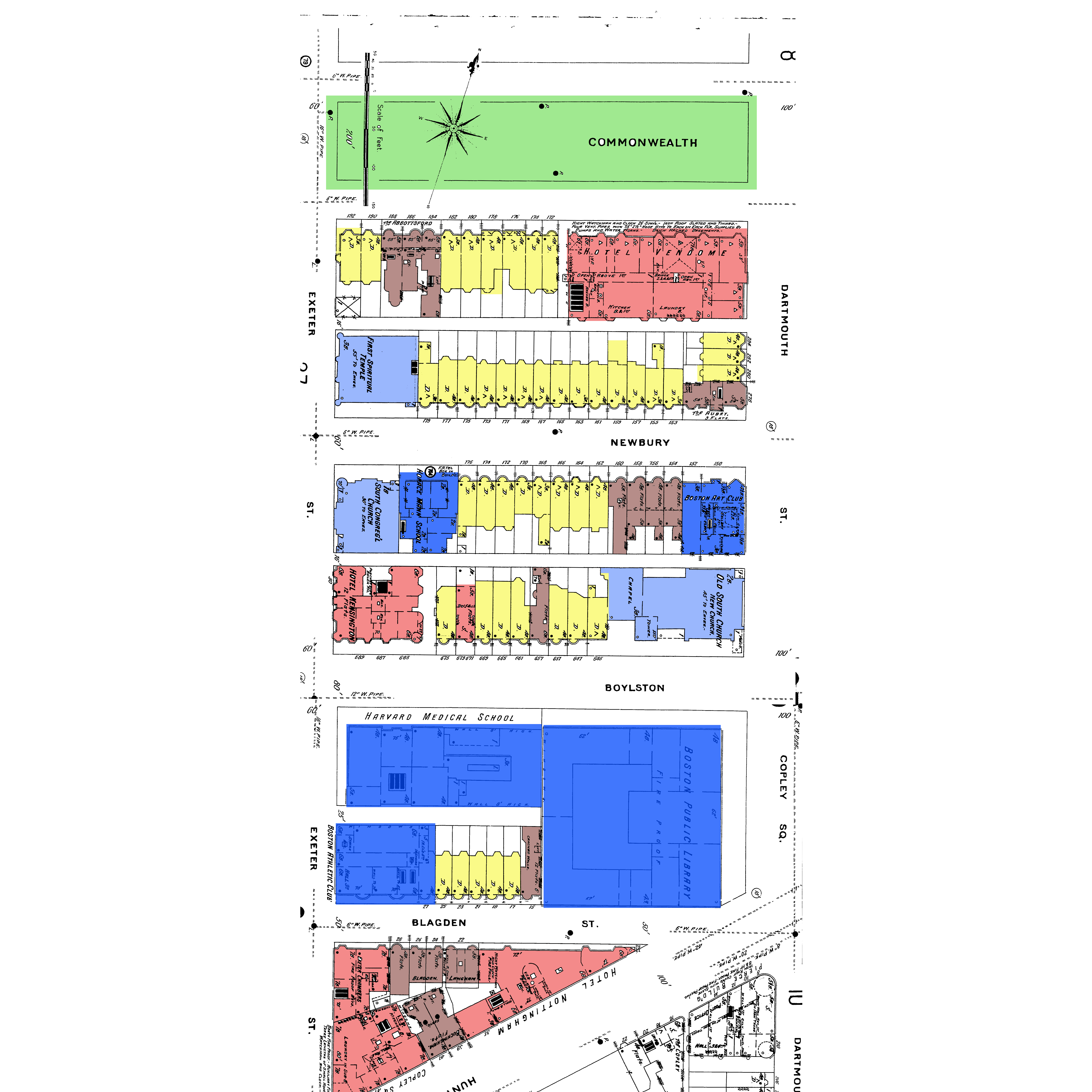

Some of these answers can be found by looking at buildings along Newbury Street. In 1898, there are three Churches on my site (see figure 1). This is the first layer of institutional buildings on my site.

Figure 1: Map of Boston in 1898. Note the Temple at the corner of Newbury St. and Exeter St. (Sanborn maps, 1898, Volume 2).

Figure 1: Map of Boston in 1898. Note the Temple at the corner of Newbury St. and Exeter St. (Sanborn maps, 1898, Volume 2).

By 1800, the Boston population was 25,000 (4.211 class website Timeline). The only areas on the map that do not appear to be fully developed are Beacon Hill and Boston Common. However, this changed in 1807 when Mill Pond was filled using the top of Beacon Hill (4.211 class website Timeline). Now, Boston was utilizing almost all of its land to build a downtown and have enough dwellings to accommodate its growing population. But would this be enough? Especially when there were limited forms of transportation between Boston and the suburbs, it was important that Boston remained central. Otherwise, people would not move into the city, and businesses could not flourish. One of the reasons Back Bay was constructed was simply to provide more land for the people of Boston.

The First Spiritual Temple at the corner of Newbury St and Exeter St in Figure 1 is of particular interest. When viewing, it initially appears to be a Montessori School. Figure 2 shows different views of the building.

Figure 2b: Zoomed in entrance of the building. An overhang similar to that of a movie theatre can be seen.

Figure 2b: Zoomed in entrance of the building. An overhang similar to that of a movie theatre can be seen.

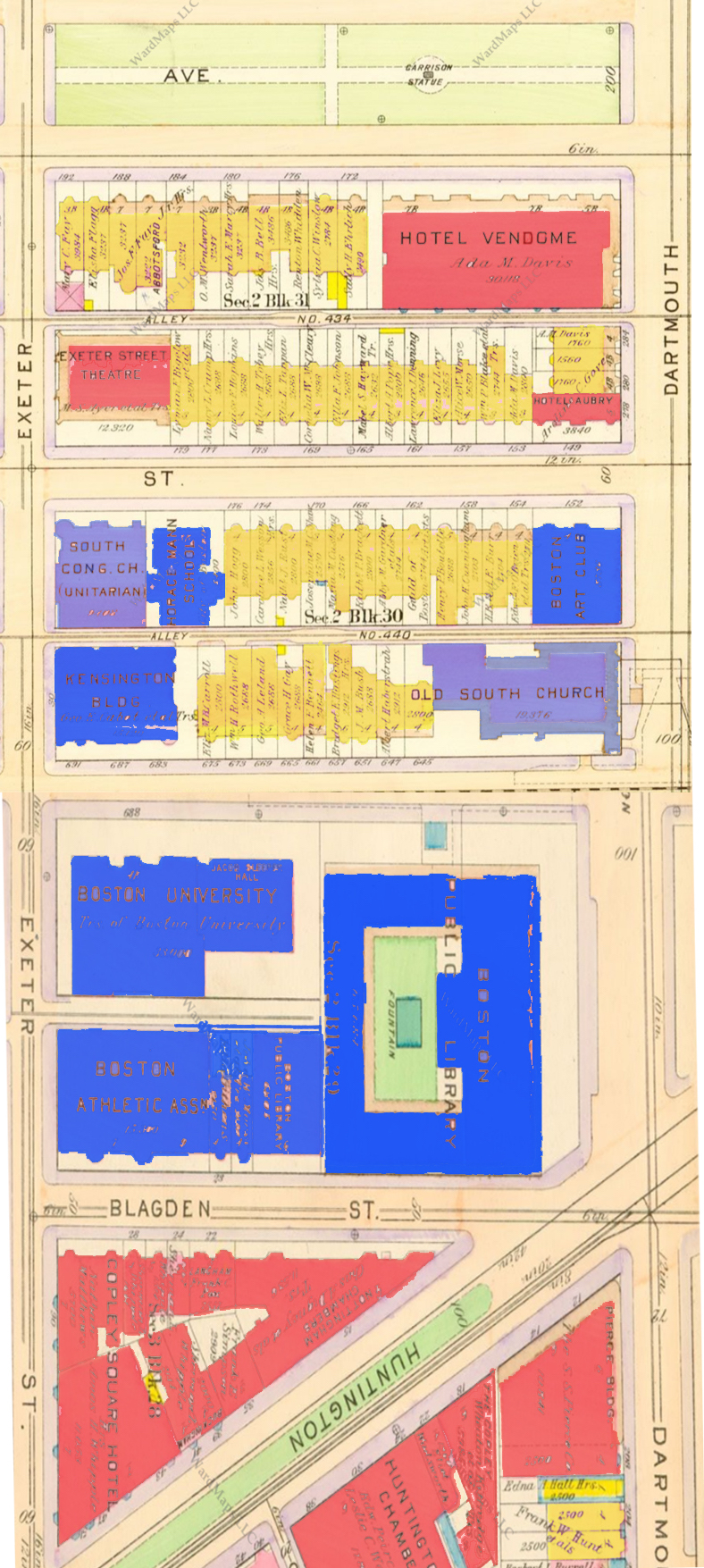

From far away (2a), the building appears to be ornate: even for the old brownstones in Back Bay, this building looks more elaborate—like a Romanesque design. When zoomed into the front entrance, the building has a modern looking overhang that contrasts the Romanesque design, but still with the First Spiritual Temple engraving, indicating it is the same building as from 1898. A map from 1917 (Figure 3) helped explain why this could be so: the overhang is actually an artifact of a past use of the building. It appears that after being a temple, the building was transformed into a movie theatre called the Exeter Street Theatre Figure 3 shows a 1917 map of my site:

Figure 3: Map of Back Bay in 1917. (Bromley Boston 1917, 1917 volume 2).

Figure 3: Map of Back Bay in 1917. (Bromley Boston 1917, 1917 volume 2).

The artifact of the overhang with lights that many theatres have is still present today. But this building represents 3 layers of Boston history. Boston was founded upon many religious principles (the “City on a Hill”), and the original Back Bay has many churches. However, over time, consumerism and entertainment begin to become more important to people. Now, the building stands on the corner of Newbury St, a shopping district, and near Commonwealth Ave, which is primarily residential. This is why it makes sense for a school to be on one entrance, and a restaurant (Joe’s) on the other end. This building has become a product of the layers of time that it has existed.

This one building says a lot about Back Bay’s trends as a whole. Why was the temple not demolished when it became a movie theatre, and then when it became a school? It has been used for incredibly different purposes, yet the original building still remains. According to Hayden, “locking history into the design of the city exploits a relatively inexpensive medium. Over time the exposure can be as great as a film or an exhibit.” (Hayden, 236). This really resonated with me: by keeping this building intact for over 100 years, the residents and visitors of Back Bay can appreciate its beauty and have pride in the area. This building, like many of the old brownstones in Back Bay, has become exhibits for those walking and visiting. This represents some desire to keep the history of Back Bay intact despite the changing technology.

2. Transportation Layers

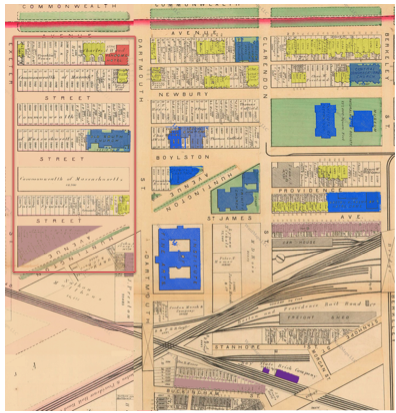

Yet there still exists a tension between the old and the new, especially as transportation technology changes. There are different layers of transportation on my site, beginning with railroads. The 1874 map below (Figure 4) shows how Huntington Avenue runs parallel to the railroad that helped define Back Bay:

Figure 4: Map of my site (outlined in red) and the surrounding area in 1874. (G.M. Hopkins and Co., Boston 1874, 1874).

Figure 4: Map of my site (outlined in red) and the surrounding area in 1874. (G.M. Hopkins and Co., Boston 1874, 1874). In this sense, Huntington Avenue is a trace of the railroad that existed before. It breaks up the otherwise grid-like organization of Back Bay. This 1874 map is the first layer in a series of layers that define the transportation in Back Bay. The railroad brought people, supplies, and commodities to Back Bay that helped it become a residential and commercial center that it is today. For example, while just speculation, the temple could have become a theatre because more people had access to Newbury Street, especially due the railway and the T.

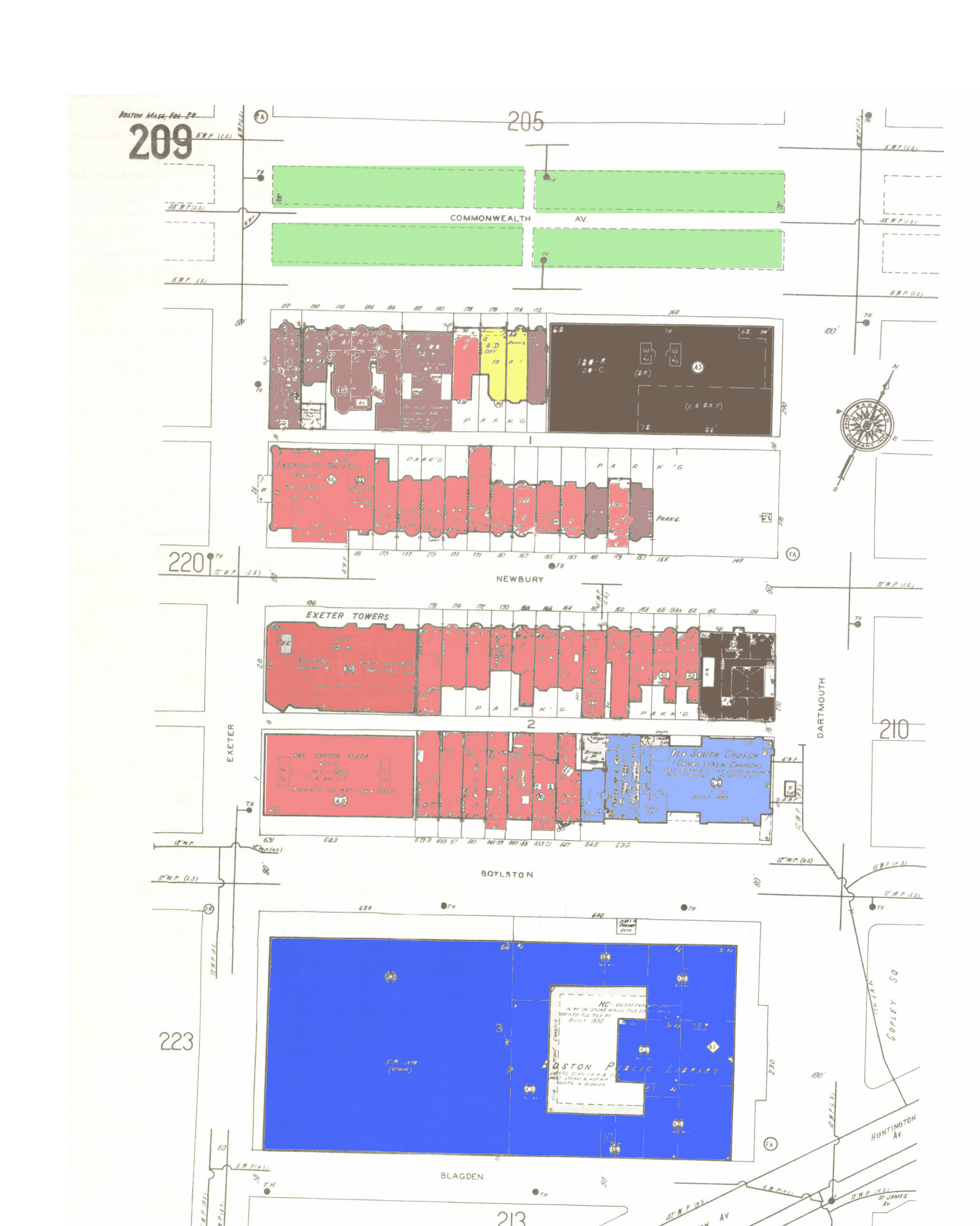

As discussed in my last paper, Back Bay became much more commercial-oriented as it became easier for people to get to Back Bay. This is in large part due to the invention of the car. In the 1917 map, there are buildings on the corner of Dartmouth Street and Newbury Street. However, by 1992 (Figure 5), these buildings are demolished and the land became parking:

Figure 5: 1992 map of Boston. Parking garages have been added to accommodate the high traffic into downtown Boston and Back Bay (Sanborn, Boston 1992, 1992).

Figure 5: 1992 map of Boston. Parking garages have been added to accommodate the high traffic into downtown Boston and Back Bay (Sanborn, Boston 1992, 1992).

Yet traces of the past are still in this parking area. Figure 6 shows the imprint on the side of a building that indicates it uses to be a shared wall with another building. Figure 7 shows the same building.

The back of the building has filled in concrete over the old brick, and the windows of the first floor are now filled in. This shows traces of the past: before cars flooded the streets of Boston, there were buildings. But as parking became more of a problem in the city, some of its history was sacrificed. According to Hayden, “As the production of built space increases in intensity and scale during the later twentieth century, the politics of space become more difficult to map” (Hayden, 42). This assertion by Hayden makes it difficult for me to hypothesize changes just due to artifacts of buildings that exist now. Maps cannot tell us why this area became a parking garage, but we do know that it led to the destruction of many historic brownstones (which maybe were damaged—who knows!) and likely brought more traffic to the area. It becomes more complicated as the addition of large highways and overpasses in Boston (such as the Big Dig) has an impact on the amount of people who can easily travel into the city. As this increases, the trend of removing buildings to accommodate for commuter traffic could also continue. Yet Figures 6 and 7 show that the rich history of Back Bay and its many layers can still not be ignored—and instead should be cherished.

3. Landmarks That Have Existed Through Time

There are many artifacts in Back Bay that seem to have been there for its entire history: the Commonwealth Ave Mall, the Boston Public Library, and the Old South Church. The Commonwealth Ave Mall has existed since my earliest map in 1874 (see Figure 1). In fact, even the statue of Garrison appears to have been in the same location on my site since 1917 (see top of Figure 3). Figure 8 shows this statue standing today:

This statue and its existence today is culturally fascinating. William Lloyd Garrison, for whom this statue is named after, was an important leader of Boston in the abolition of slavery, as well as woman’s rights. One line of the side of the statue is, ““I am in earnest - I will not equivocate - I will not excuse - I will not retreat a single inch- and I will be heard!”. This quote is incredibly relevant to the attitudes of Back Bay and its history: in many ways, it remains a single historic layer of a time when Boston was (and probably still is) one of the great educational and ideas center of the world. As Hayden asserts, “When we know our own engaging and difficult history as a nation… we can begin to create public places, in all parts of our cities, to mourn and celebrate who we really are” (Hayden 238). This statue as well as many other artifacts in Back Bay show the importance people have placed on preserving its history, and the history of Bostonians. The fact that this statue has been preserved represents a greater desire of the people of Back Bay to keep its history alive.

This trend continues as one approaches Copley Square. The Old South Church is a large Church right in the middle of Copley Square that is reminiscent of Gothic styles. Figure 9 shows a photo taken from a distance.

Figure 9: View of the Old South Church from Copley Square (Tripadvisor, 2015).

Figure 9: View of the Old South Church from Copley Square (Tripadvisor, 2015).

As one approaches this landmark, it becomes apparent how rich the history of this building is. Figure 10 shows a plaque on the side of the Church that shows the dates in which it was rebuilt, while Figure 11 is a plaque indicating the Church was moved to this location in 1875.

The Old South Church adds dimension to the original layer of Back Bay seen in the 1898 map. The Church was moved to Copley Square from a different location, indicating that Copley Square and this area of Back Bay could have been a residential center that needed Churches. Just like the First Spiritual Temple, it represents the importance put on architectural beauty in this time period. Because the Old South Church is a historic landmark now, it will remain an artifact of Boston’s more religious past, and Back Bay’s residential past.

Right across the street from the Old South Church is the Boston Public Library. While it seems to contrast the Old South Church in its purpose, they are both similar in that they are architecturally complicated, in the same historic layer, and still remain central to Copley Square. The Boston Public Library is symbolic of a layer of time when Back Bay was also a center for education. In various maps from my past essay, it can be seen that Boston University was in the area, MIT was in the area, and even Harvard was in the area. This layer in the early 1900s represents a transformation of Boston and Back Bay from a purely rich residential area, to an area rich with knowledge. The Boston Public Library is an artifact of this time. Figure 12 shows the front of the library.

Figure 12: View of the Boston Public Library from Dartmouth St.

Figure 12: View of the Boston Public Library from Dartmouth St.

Yet the Boston Public Library provides a lot of mixed trends for Copley Square going forward, and these can be seen across Back Bay as a whole. Figure 13 shows the side of the Boston Public Library seen from Boylston Street. The left half is the old Boston Public Library, and the right half is the recent addition to the Boston Public Library.

This says a lot about where Copley Square is heading. The left half is beautiful, inspiring, and has been well preserved. But the right side is essentially a block of concrete. Both help compose a large library, but the right half is modern and in itself a different layer. Education is important to the people of Boston, but potentially the history of the architecture of the Boston Public Library is becoming less important. Even as one walks down Boylston St, there are brownstones next to new, modern looking buildings. Figure 14 shows a brownstone on the right being overtaken by a new AT&T building on the left. This picture shows a trend in the area of commercialism overtaking history. It begs the question: is it even possible to compromise history and innovation?

4. Preservation or Destruction? Expected Trends in Back Bay

Some attempts have been made to preserve the historical feelings of Back Bay while embracing new technology. Figure 15 shows a close-up photo of the entrance of the Boston Public Library, while Figure 16 shows the entrance of the Copley Square T station.

The T station came after the Boston Public Library, but architects designed it to have the same Gothic architecture. This makes the T fit in with its surroundings. This shows an effort of people to maintain the culture of the area and make the T less of an eyesore. It also creates a feeling of timelessness in the area, and makes one feel like they are visiting a piece of history. But as you zoom out a little bit, you see an ominous trend appearing: the influence of commercialism. Figure 17 shows the Copley Square T entrance juxtaposed with the advertisement a few feet away.

While people seem to care about maintaining the history of Back Bay and Copley Square, it has become evident that there is a tension between commercialism and historic districts. Figure 18 is an ominous picture of a new building outgrowing a brownstone building on Newbury St.

This photo shows that much of Back Bay is experiencing tensions between old and new. Should the historic and beautiful architecture be sacrificed for more modern buildings? Is it worth sacrificing the identity of Back Bay to make the area fit in with modern-day cities? It is hard to really know the balance, or even if there can be a balance.

What does this say about Back Bay going forward? Right now, it seems unclear. There are almost no plaques on buildings designating them as historic; so many of the beautiful brownstones on my site could be demolished, just as they were for the parking lot. Yet there are also signs of people wanting to maintain a historical presence, such as the many uses of the Montessori School on Newbury Street, the Commonwealth Ave Mall, the Old South Church, and the Boston Public Library. But what happens when this becomes economically unfeasible, or when the trends of the area lean towards commercialism?

As Hayden explains, there are many factors that go into an urban landscape. There is a delicate balance of the people who live in an area, the government officials, and contractors that determines how an area develops. Hayden states, “As the productive landscape is more densely inhabited, the economic and social forces are more complex, change is rapid, layers proliferate” (Hayden 17). As transportation made Back Bay accessible, and as businesses started to move in, Back Bay could no longer be isolated from many of the social and economic changes. Going forward, the trend might be that a lot of its history is lost to commercialism.

Yet there will always be a sense of historical pride in Back Bay. For example, on Commonwealth Ave and Dartmouth St, a hotel called Hotel Vendome existed for much of history (see Figure 1). Now, it is apartment complexes. Yet they pay homage to this historical building by calling them the “The Vendome”. Figure 19 shows the front door and sign of The Vendome.

Even as Back Bay transforms into a more commercial-friendly area, there is always going to be rich history. The layers may change, but there will always be artifacts of a time when Back Bay was a residential center.

The images in this paper present a complicated story of Back Bay and its future. There are buildings that have been repurposed multiple times, buildings that remained unchanged, and buildings that no longer exist because of the changing needs of the residents. It seems that people are battling whether or not to incorporate modern buildings and commercial centers into Back Bay, or to keep the historic buildings and purposes from previous times. As Boston continues to grow and attract industry and commercialism, Back Bay will likely succumb to this trend. Yet the peoples’ attachment to their “place”, as described in Hayden, remains, Back Bay will always pay some homage to its history.

Image Sources:

All images by the author unless otherwise noted below.

[1] Boston, Massachusetts [map]. 1898. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1898". Digital Sanborn Maps 1867-1970. (7 Apr 2015).

[3] Bromley, G.W. 1917 Atlas of Boston.1917, “Atlas of the City of Boston: Boston Proper and Back Bay,” Massachusetts Real Estate Atlas Digitization Project. < http://www.mass.gov/anf/research-and-tech/oversight-agencies/lib/massachusetts-real-estate-atlases.html> (6 Apr 2015).

[4] Boston, Massachusetts [map]. 1874 “Boston Back Bay: G.M. Hopkins and Co.”. Digital. Wardmaps Antique Maps < http://www.wardmaps.com/browse.php?cont=1&count=1&state=1&city=1>(6 April 2015).

[5] Boston, Massachusetts [map]. 1992. "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1992".

[9] “Old South Church images”. Tripadvisor. Accessed May 1, 2015. http://www.tripadvisor.com/Attraction_Review-g60745-d279055-Reviews-Old_South_Church-Boston_Massachusetts.html

Works Cited

[1] Hayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1995. Print.