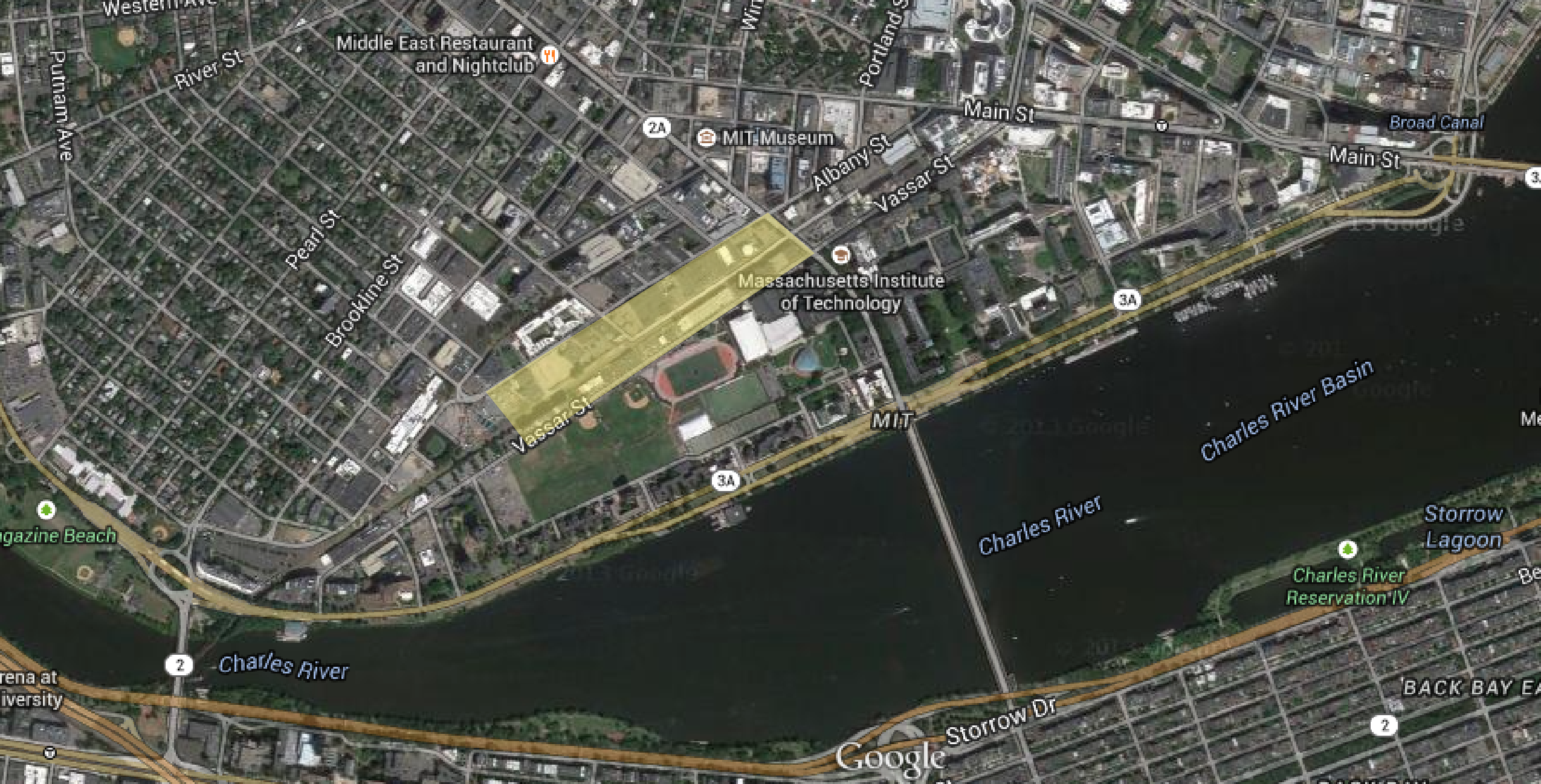

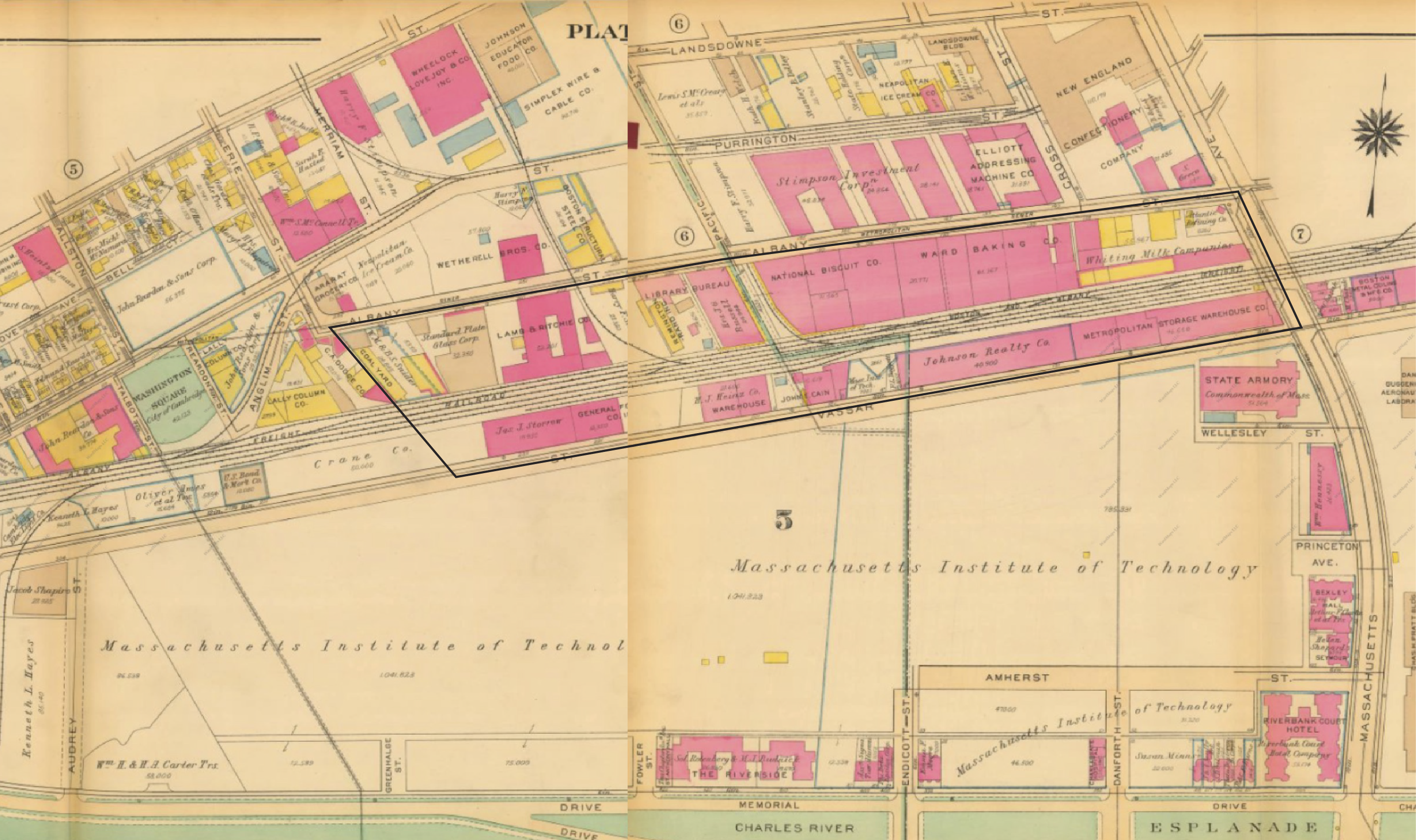

Figure 1: Map showing site today highlighted in yellow, Cambridge,MA| Map data ©2015 Google, Sanborn, Cnes/Spot Image, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agency.

Figure 1: Map showing site today highlighted in yellow, Cambridge,MA| Map data ©2015 Google, Sanborn, Cnes/Spot Image, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agency.

Each site has its own story, shaped and reshaped by historical events, economic

and social trends, and technological advances, molded by powerful individuals, institutes,

corporations and entire societies. In just over one century, from the mid 1800s to the late

1900s, forces of industrialization, zoning policies, a rising automobile age and

institutional expansion have come together to form the drastic evolution of my site

(figure 1).

In this paper I attempt to trace the evolution of my site over time by comparing its

characteristics at several points in history using various types of maps and atlases. I start

by looking at maps from the year 1854 and end by studying maps of my site today. I have

noticed different kinds of changes such as: land use, density of settlement, ownership,

and transportation.

I start my investigation by locating the site on a 1854 map of Cambridge (figure 2). The map above depicts a Cambridge almost unrecognizable from the one we know today (figure 1). It’s hard to believe that more than one hundred and sixty years ago, my site was a tidal flat and water, as it is a far cry from the bustling urban area it is today.

Figure 2: Site location in 1854 highlighted in yellow, Cambridge, MA | 1854 Map of Cambridge by H.F Walling.[1]

Figure 2: Site location in 1854 highlighted in yellow, Cambridge, MA | 1854 Map of Cambridge by H.F Walling.[1]

The evolution of my site starts in the early 1800s when Cambridge was billed as a

shipping port. Developers invested heavily in roadways to funnel traffic across the new

bridges between Cambridge and Boston. But the War of 1812 brought a blockade to the

East Coast, hindering plans for Cambridge’s rise as a commercial center.[2] The city of

Cambridge was left with a grid of roads and vacant spaces in between as seen in the map

above, figure 2. It had plots and streets laid out, but didn’t have a huge residential

population, making it a great area for new industries to move into.

By the beginning of the Civil War, Cambridge was thriving as an industrial town.

And as any other industrial town, Cambridge needed a railway. In 1853 the Grand

Junction railroad was built across the flats to tie Boston to East Cambridge industries.

The railroad passes right through my site dividing it in half. The railroad had a great

effect on the transformation of my site as observed through out the paper.[3]

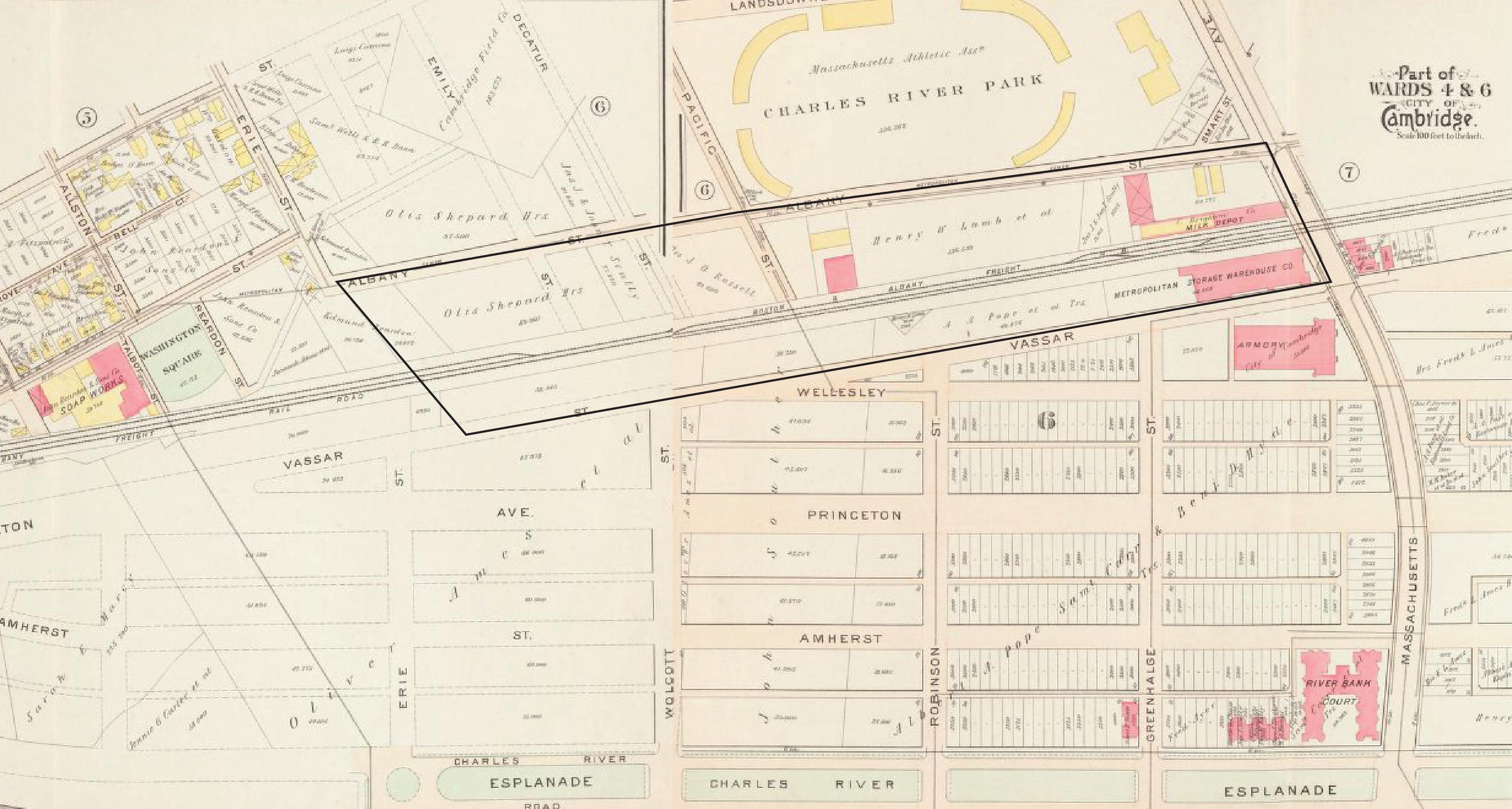

Figure 3: Site location inside black border, Cambridge, MA | 1903 Map of Cambridge, Atlas of the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts by G.W. Bromley and Co.. As you can see, the site was filled with artificial land and divided into plots and properties. Barely any development has taken place—MIT is still based in

Copley Square, and very few factories have been built.[4]

Figure 3: Site location inside black border, Cambridge, MA | 1903 Map of Cambridge, Atlas of the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts by G.W. Bromley and Co.. As you can see, the site was filled with artificial land and divided into plots and properties. Barely any development has taken place—MIT is still based in

Copley Square, and very few factories have been built.[4]

By 1903, the Charles River Embankment Company built the sea wall on

Memorial Drive, filled the land and laid down a subdivision similar to the Back Bay,

using the college names to label its streets, such as Princeton, Wellesley and Albany,

hoping perhaps to give this new residential development some cachet.

As seen from the map above, figure 3, the site was divided into plots and

properties, mainly owned by 4 major owners. Most of the properties were vacant at the

time, except for the ones that were occupied by the Metropolitan Storage Warehouse and

The C. Brigham Co. Milk Depot -which would later become Nabisco (figure 4).

The Grand Junction railroad revolutionized the movement of goods on site,

making it cheaper and faster to move large quantities of freight. This coupled with the

rather large sizes of properties may be why my site was used for storage and industrial

purposes over the years.

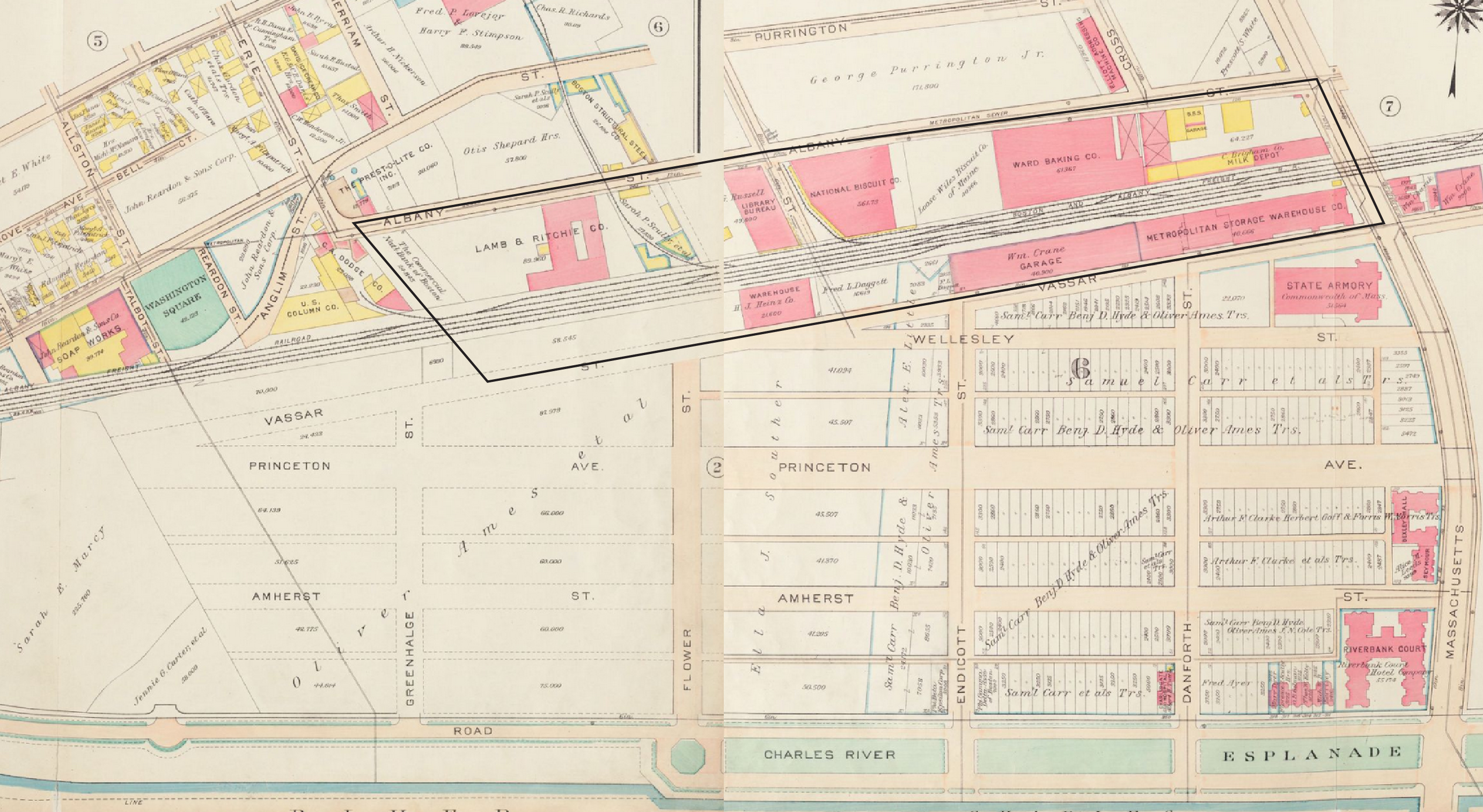

Looking forward to over a decade, this 1916 Bromley Map above, figure 5,

demonstrates significant change and establishes a precedent for the site’s economic

activity: focusing on the food industry. In the 1903 map, the only labeled businesses were

The C. Brigham Co. Milk Depot and Metropolitan Storage Warehouse. Few years later, a

large portion of the site is dedicated to the food industry, mainly baking.

Fast forward to 1930, and Bromley Maps above, figure 6, shows a variety of

factories around MIT, which by now has relocated from Copley Square to Cambridge, as

well as an expanded Grand Junction Railroad with extra tracks along the main railroad.

The Railroad evidently has to accommodate much more freight traffic than it did in 1916,

as many more factories serving a variety of industries now line the railroad.

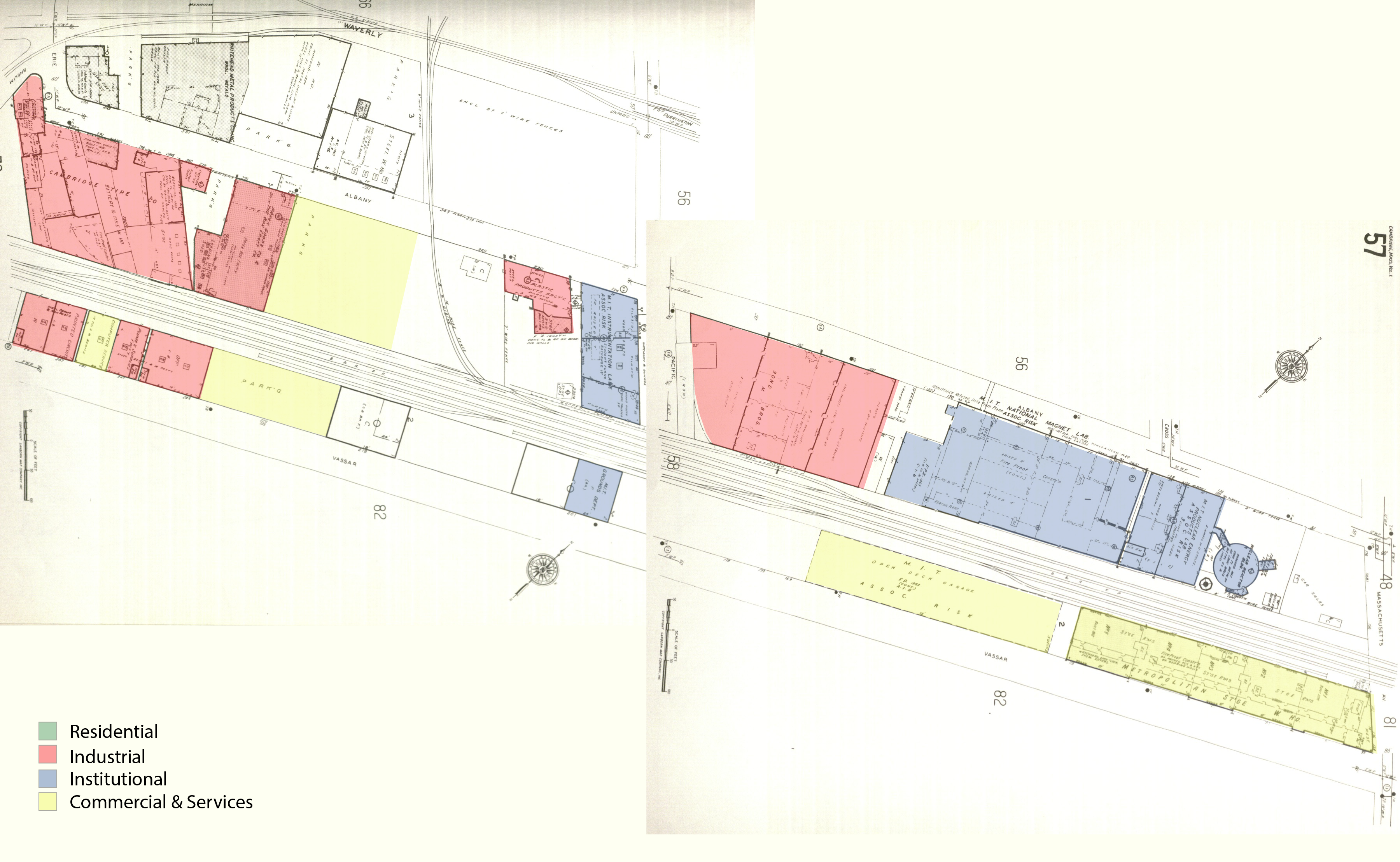

The next glance into the history of my site comes in 1970 by means of a Sanborn

map. By 1970, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has acquired portion of my

site as part of MIT campus expansion project for undergraduate housing. This purchase

can be considered part of an urban renewal scheme, where the government, according to

Jackson, could “stimulate building without government spending…by relying on private

enterprise to ‘encourage improvement in housing standards and conditions.[10]

The arrival of the automobile brought a gradual change to my site as well. By

1988, few buildings on my site were demolished to make room for parking lots such as

the Plywood Warehouse on Vassar St or the Lamb & Ritche Metal Works Company on

Albany Street. Jackson explains that the car, “even in its primitive form before World

War I, could do four times the work of a horse-drawn wagon which took up the same

street space”. Hence the addition of the car was a necessity worth tearing a few

warehouses to the ground.[12]

In addition to tearing down few buildings, a portion of the railroad connecting

Vassar Street and Albany Street was removed in 1996 (figure 10). This is a peculiar

occurrence that is hard to make sense of. There is nothing on the map that can help shed

light on what happened. Maybe Boston & Albany Railroad Company decided that the

railroad was no longer the most profitable use of the land and decided to turn it into

parking as well.

Fast forward to the site today, we notice that many of the industrial buildings

originally built on site are now either occupied by similar businesses or were converted to

offices or housing spaces for students, as many buildings around MIT have been bought

by the university and no longer serve as industrial properties. For example, the Heinz

Storage Warehouse has been turned into ROTC offices or The Warehouse on Albany

Street that has been changed into a graduate dorm.

In just over one century, my site has drastically transformed due to forces of

industrialization, zoning policies, a rising automobile age and institutional expansion. By

tracing a site’s history through maps and comparing its characteristics, one can get a

glimpse into the changes that have occurred over time, such as changes in land use,

density of settlements, ownership, and transportation, and can analyze the the driving

forces behind them.

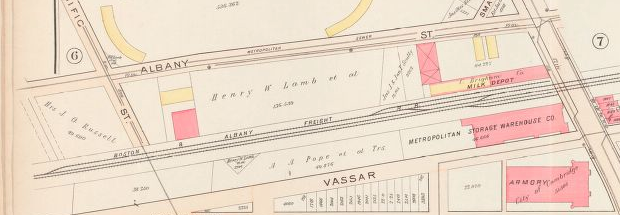

1. 1854 Map of Cambridge by H.F Walling: http://ids.lib.harvard.edu/ids/view/7933307?buttons=y  Figure 4: A Closer look at the site showing The Metropolitan Storage Warehouse and Milk Depot | 1903 Map of Cambridge, Atlas of the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts by G.W. Bromley and Co.[5]

Figure 4: A Closer look at the site showing The Metropolitan Storage Warehouse and Milk Depot | 1903 Map of Cambridge, Atlas of the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts by G.W. Bromley and Co.[5]

Figure 5: Site location inside black border, Cambridge, MA | 1916 Map of Cambridge, Atlas of the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts by G.W. Bromley and Company. [6]

Figure 5: Site location inside black border, Cambridge, MA | 1916 Map of Cambridge, Atlas of the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts by G.W. Bromley and Company. [6]

One question that the location of these building raises is why a milk company

would be located here. The maps don’t hold the answer, but they may contain clues. One

such clue is the proximity to such the Grand Junction railroad, which must have been

very beneficial.

As stated earlier, the reason that the milk company was located on my site cannot

be known, however, the existence of baking factories on Vassar Street can definitely be

explained by location of the milk company. Perhaps The C. Brigham Co. Milk Depot

could have provided milk and other resources to the National Biscuits Company or the

Ward Baking Company adjacent to it (figure 5).

By 1916, more tracks were added to the Grand Junction railroad. The addition of

tracks might have been a result of the appearance of the new factories on site such as The

Ward Baking Co. and The National Biscuits Co. next to the already established Milk

Depot or the WM. Crane Garage and Heinz Storage that were built next to the

Metropolitan Storage Warehouse.

These few factories and storage warehouses along the Grand Junction Railroad

had railroad spurs connecting them to the main railroad, allowing shipments to be

delivered directly to and from factories and ensuring that traffic can flow freely along the

railroad without blocking traffic flow with stopped trains.

Another important observation from the map above is the lack of residential

buildings on the site, perhaps because it is less desirable to have residences bordering the

smoke, soot, and noise of the railroad. Kenneth Jackson notes in his book, Crabgrass

Frontier, that in 1839 a locomotive boiler exploded at Fourteenth Street in New York

City, killing the engineer and injuring twenty passengers. As a result of this and other

accidents, fear of the big engines became widespread, leading to less residential buildings

near railroads, explaining the case of my site.[7]

Figure 6: Site location inside black border, Cambridge, MA | 1930 Map of Cambridge, Atlas of the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts by G.W. Bromley and Company. Map showing the expansion of The Ward Baking

Co. and National Biscuit Co. taking over almost half of the site.[8]

Figure 6: Site location inside black border, Cambridge, MA | 1930 Map of Cambridge, Atlas of the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts by G.W. Bromley and Company. Map showing the expansion of The Ward Baking

Co. and National Biscuit Co. taking over almost half of the site.[8]

During this industrial heyday, my site hosted the main complex of the Whiting

Milk Company, the Ward Baking Company, the National Biscuit Company, John Cain

Salad Dressing Company and more, including a Heinz warehouse that once stored

ketchup and mustard.

Figure 7: 1970 Sanborn map showing my site highlighting the different land uses, Cambridge, MA | 1970 Sanborn Atlases of Cambridge. [9]

Figure 7: 1970 Sanborn map showing my site highlighting the different land uses, Cambridge, MA | 1970 Sanborn Atlases of Cambridge. [9]

Although MIT acquired the land as an undergraduate housing resource, there

were no residential buildings on site yet. Instead, both the Milk depot and The Ward

Baking Company were destroyed and replaced by MIT Nuclear Energy Lab and MIT

National Magnet Lab. This marks the shift in land uses on my site from mainly

commercial and industrial to institutional land uses.

Figure 8: 1988 Sanborn map showing my site and highlighting the different land uses, Cambridge, MA |1988 Sanborn Atlases of Cambridge.[11]

Figure 8: 1988 Sanborn map showing my site and highlighting the different land uses, Cambridge, MA |1988 Sanborn Atlases of Cambridge.[11]

Figure 9: 1996 Sanborn map showing my site and highlighting the different land uses, Cambridge, MA | 1996 Sanborn Atlases of Cambridge.[13]

Figure 9: 1996 Sanborn map showing my site and highlighting the different land uses, Cambridge, MA | 1996 Sanborn Atlases of Cambridge.[13]

Another change came in 1988, when the rezoning of the district reduced

allowable development by 25% and established the district as a residential zone.[14] As a

result many buildings were demolished afterwards such as the John Cain Salad Dressing

Company that had occupied the space since 1930’s (figure 9).

Figure 10: MIT campus map showing the site in red,Cambridge, Ma. [15]

Figure 10: MIT campus map showing the site in red,Cambridge, Ma. [15]

This phenomenon resulted in a wide spectrum of land-uses visible on the site

today. For instance, there are multiple residential buildings now such as the

undergraduate dorm, Simmons Hall, or the graduate dorm, The Warehouse. There are

also few commercial buildings like the Heinz Building (ROTC), the Metropolitan

Moving & Storage and MIT West Garage. You can also find institutional buildings such

as the Plasma Science & Fusion Center, Francis Bitter Magnet Lab, Nuclear Reactor

Laboratory, or the David H. Koch Childcare Center. This is a drastic change in comparison

to the site few decades earlier, which had only industrial and commercial

buildings.

All the buildings listed above are MIT owned buildings now, with the exception

of the Metropolitan Moving & Storage building. These buildings work together to

support the neighboring buildings and the entire MIT community, the same way the Milk

Depot supported the baking company decades earlier. For example, The David H. Koch

Childcare Center, close to the graduate dorm, The Warehouse, is used by graduate

students with kids as well as MIT faculty and staff. Although the Metropolitan Storage is

not part of the MIT campus, it also supports the needs of the MIT community by

providing storage and moving services for students.

2. Nidhi Subbaraman, “The Evolution of Cambridge,” The Technology Review (2010), accessed April 10,

2015.

http://www.technologyreview.com/article/422108/the-evolution-of-cambridge/

3.Simha, O. Robert. MIT Campus Planning, 1960-2000: An Annotated Chronology. (MIT Press:

Cambridge, MA. 2001), 135.

4. 1903 Map of Cambridge, Atlas of the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts by G.W. Bromley and Co.

http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/6153086

5.ibid.

6.1916 Map of Cambridge, Atlas of the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts by G.W. Bromley and Co.

http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/6592027

7.Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1985), 38.

8.1930 Map of Cambridge, Atlas of the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts by G.W. Bromley and Co.

http://www.wardmaps.com/viewasset.php?aid=11

9. 1970 Sanborn Atlases of Cambridge:http://sanborn.umi.com/cgi-bin/auth.cgi?command=AccessOK&CCSI=254n

10.Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1985), 203.

11.1988 Sanborn Atlases of Cambridgehttp://sanborn.umi.com/cgi-bin/auth.cgi?command=AccessOK&CCSI=254n

12.Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1985),183.

13. 1996 Sanborn Atlases of Cambridge:http://sanborn.umi.com/cgi-bin/auth.cgi?command=AccessOK&CCSI=254n

14. Simha, O. Robert. MIT Campus Planning, 1960-2000: An Annotated Chronology. (MIT Press:

Cambridge, MA. 2001), 135.

15. MIT 2030: http://web.mit.edu/mit2030/framework.html