“Nature has been seen as a superficial embellishment, as a luxury, rather than as an essential force that permeates the city” - from The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design by Anne Spirn

Figure 1: Diagram of site, overlayed on Google Maps document, where the highlighted streets indicate the boundaries of the site. The color red is used to demonstrate the presence and absence of wind (by arrows and crosses, respectively) but also the gradient of snow since there is a direct correlation of quantity and presence of snow with the wind patterns.

Figure 1: Diagram of site, overlayed on Google Maps document, where the highlighted streets indicate the boundaries of the site. The color red is used to demonstrate the presence and absence of wind (by arrows and crosses, respectively) but also the gradient of snow since there is a direct correlation of quantity and presence of snow with the wind patterns.

When thinking of the modern city, one usually distinguishes it from the idyllic countryside, considered Nature personified. As was stated in Granite Gardens, one has “learned to doubt that the city was part of nature.” This could not be more wrong since a city contains as much wildlife, not necessarily desirable but still existent, as the countryside while also hosting vegetation and human beings. The presence of a city, with its cement and asphalt overlaying the surface, and foundations going deep into the ground, in comparison to the rolling pastures of the countryside, is still part of the natural environment. Having these man-made structures such as streets and buildings has repercussions on the natural processes of the surrounding area in multiple ways: the breaks created by the city streets affect the wind patterns, the different ways the area was transformed shape the ground underneath, and the houses present distort the effect of sunlight in the environment.

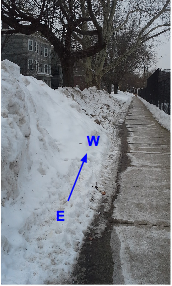

Figure 2: Gradient of snow along York St, from east to west, decreasing

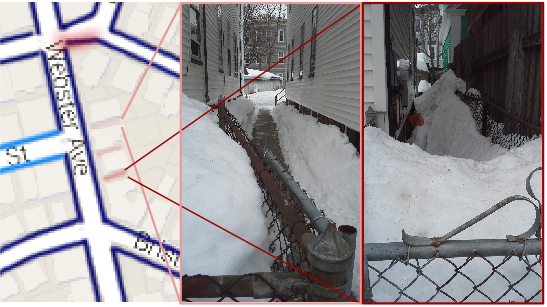

Figure 2: Gradient of snow along York St, from east to west, decreasingThere were several ways of qualitatively identifying wind patterns on the site, when considering its relation to the deposition of snow. As can be seen on Fig. 1, there were two distinctions made for wind: in red is the presence of wind, shown with arrows, and absence, shown by crosses, as it was physically felt on the site; in orange, the overall direction of wind, from the northeast, during the winter storms that have been taking place over the past month is shown. These two instances can be correlated since the visits made to the site were during the start or end of the winter storms, indicating continuity in the wind pattern. These findings are supported by both the presence of snow throughout the area and the knowledge of wind behavior. In the case of the snow, one can assume that even though the snow observed had been moved by snowplow or shovel, the distance it was moved was minimal. If anything, it was pushed to the side of the street but not moved towards a particular side of the street. Thus, gradients in snow accumulation were clearly visible and could be quantified, and were indicated on the map (Fig. 1) by an increasing redness for an increasing quantity of snow. Similarly, this behavior is supported by an explanation of wind patterns, as presented in Granite Garden. Over a city, winds will slow down over the buildings because of the friction presented but speed up if coming across an open space like Donnelly Field, which is to the north-northeast of the area studied. Since the buildings are all of similar height around the field, the funneling of the wind into the streets will simply depend on the direction of the wind and streets, and not on a tall building pulling stronger winds down to the ground for example. When wind comes into contact with a building, it will actually split off into branches: one slowing down while going over the building, meaning that a reduced speed will dump snow behind the structure; two going around from each side increasing speed; and another going down to the base of the building upon initial impact, clearing the snow. So, in the case of York St, on the western side of the street the snow was cleared by the full force of the wind, whereas the eastern side came into contact with a slower wind that was coming over the building and not the open field, whereby it received a lot more snow (Fig. 2). Other examples of wind losing speed and dumping the snow it was carrying were along Webster Ave by Seckel Street, and at the intersection of Plymouth and Hamlin St (can be seen on Fig. 1). The second intersection is a case where the wind changed direction and an eddie, or area of reduced speed, was created. This could also be seen with the houses along Webster Ave that backed a courtyard: by all having an orientation towards the south-west, these houses were all prone to create eddies when in contact with the wind; however, the speed of the wind must have been related to the surface of courtyard it covered, since as the free space the wind covered increased, the more snow was accumulated in between the houses (Fig. 3). Thus, the presence of buildings has deeply affected the natural movements of wind in this area, by diverting and concentrating its course.

Figure 3: Comparison of snow accumulated in between houses, where the image on the far left is a close up of the map, the image in the middle has very little snow, and the image on the far right has a lot more snow. Even though the middle image shows the snow having been cleared, one can still see the difference in quantities of snow.

Figure 3: Comparison of snow accumulated in between houses, where the image on the far left is a close up of the map, the image in the middle has very little snow, and the image on the far right has a lot more snow. Even though the middle image shows the snow having been cleared, one can still see the difference in quantities of snow.

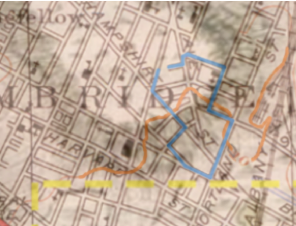

Figure 4: Overlaid maps, where the background is the topographical maps, and the overlaid drawing is the 1776 version. In orange is the topographical line to indicate 10 feet in elevation and in light blue is the boundaries to the site. Note that Seckel St was unfinished at the time.

Figure 4: Overlaid maps, where the background is the topographical maps, and the overlaid drawing is the 1776 version. In orange is the topographical line to indicate 10 feet in elevation and in light blue is the boundaries to the site. Note that Seckel St was unfinished at the time.

Along with the presence of buildings, the presence of streets pervading our cities have had an effect on the surrounding environment. For this particular site, the timeline of construction had a particular importance since it indicated the initial topography of the land. As can be seen on the overlaid map in Fig. 4 from 1776, there was a drumlin, sediment left by a past glacier, that dotted this Cambridge area. This can be confirmed in the topographical map of 1954, which shows an elevation of 10 feet throughout the middle of the site, approximately lining up with the border of the past drumlin. The interesting aspect of this finding is that the site itself is very flat: either the slope is so small that it is barely noticeable, or the land elevation was modified during some landfilling taking place in the neighborhood. The site studied here sat approximately on one of the drumlins slopes, which influenced the routes of transportation shown on the 1776 map: either they tried to avoid the hill, like Broadway, or they went directly up the slope perpendicularly, like Webster Ave and Hampshire St. Throughout the years, the area was developed, with several other streets being created before 1852 (Fig. 1), before the wave of construction of the late 19th century. Establishing a timeline of the development of the area was difficult because of the lack of interest in mapping the Cambridge area in the historical maps, and if this was done, with its focus on only the major streets, letting the existence of the smaller streets only to be guessed at. At the very end of the 19th century, Donnelly Field was established, as one of the last key elements of Area IV, which would make York St one of the youngest streets in the site. When studying the road on York St, however, the road is much worse shape than its surrounding streets.

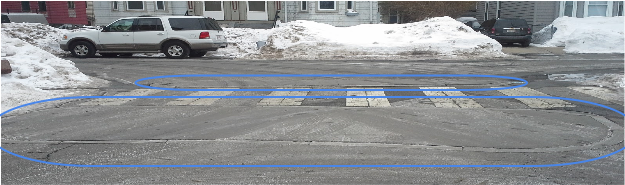

Figure 5: Fatigue cracking around the main entrance of the park. Note the pool of ice forming between the sidewalk and the road, just as the crack is propagating through the cement. Also note the potholes that seemed to have been filled on the top left image.

According to Elkins, “fatigue cracking” like the one that can be seen Fig. 5 can be caused by overuse and bad drainage, which both seem probable. Bad drainage is currently taking place with the quantity of snow on the street the drains being covered by the snow and ice, and the fluctuating temperatures causing the snow to melt and form into ice. Overuse is also a possible cause since York St is the fastest way to get around the field back to Cambridge St, which has a lot of traffic, but also because all of the houses along York St seem recently built, which would indicate the passage of trucks in the area for construction purposes. Before the field was put in place, in its stead were several blocks of housing, demolished between 1874 and 1898. A possible indicator of a different use of land in the area is Depina Sq, the western corner of the field with Webster Ave. There were two oval cement rings in the ground that were filled with cement at some point recently, in the middle of the intersection. From how they were disposed towards one another, these could have once been the location of flowerbeds (Fig. 6). But most importantly, the junction of the streets point towards the existence of an actual square that then needed to be converted into a more efficient street once traffic was diverted into York St. In this way, there is visibly a back and forth between the man-made elements inserted in the natural environment having an effect upon it, and the natural environment changing the new elements.

Figure 5: Fatigue cracking around the main entrance of the park. Note the pool of ice forming between the sidewalk and the road, just as the crack is propagating through the cement. Also note the potholes that seemed to have been filled on the top left image.

According to Elkins, “fatigue cracking” like the one that can be seen Fig. 5 can be caused by overuse and bad drainage, which both seem probable. Bad drainage is currently taking place with the quantity of snow on the street the drains being covered by the snow and ice, and the fluctuating temperatures causing the snow to melt and form into ice. Overuse is also a possible cause since York St is the fastest way to get around the field back to Cambridge St, which has a lot of traffic, but also because all of the houses along York St seem recently built, which would indicate the passage of trucks in the area for construction purposes. Before the field was put in place, in its stead were several blocks of housing, demolished between 1874 and 1898. A possible indicator of a different use of land in the area is Depina Sq, the western corner of the field with Webster Ave. There were two oval cement rings in the ground that were filled with cement at some point recently, in the middle of the intersection. From how they were disposed towards one another, these could have once been the location of flowerbeds (Fig. 6). But most importantly, the junction of the streets point towards the existence of an actual square that then needed to be converted into a more efficient street once traffic was diverted into York St. In this way, there is visibly a back and forth between the man-made elements inserted in the natural environment having an effect upon it, and the natural environment changing the new elements.

Figure 6: Depina Sq, with its two cement ovals in the ground marked in blue.

Figure 6: Depina Sq, with its two cement ovals in the ground marked in blue.Another natural process that has been adapted to its surroundings is the formation of icicles. Under normal circumstances, icicles form when the snow starts melting by solar insolation, and then freezing because the ambient temperature is below the freezing temperature of water. Throughout the site, there were several examples of icicles, but not all of them were formed in following the standard procedure. For example, Fig. 7 depicts an example of icicles forming by solar insolation: the icicles only

Figure 7: Icicle formation on the southwest side of the building, demonstrating solar insolation

Figure 7: Icicle formation on the southwest side of the building, demonstrating solar insolation

Figure 8: Icicle formation all along the eave of the house, demonstrating bad insulation

Figure 8: Icicle formation all along the eave of the house, demonstrating bad insulation

form on the southwest side of the

building, which receives the most sunlight. It is also the side of the building that received the most snow, since the winds have been blowing from the northeast and decreasing in speed over buildings. Finally, the proximity to the chimney can be ignored as a reason for the icicles forming since the icicles form all along the eave of the building, not just on the area directly underneath the chimney where the heat would induce the snow melting. Figure 8 on the other hand depicts the formation of icicles due to poor insulation. This can be deduced by the sheer quantity of icicles forming all along the eave, with no preference to cardinal direction. No longer having any snow on the roof shows that the snow melted on the whole of the surface, and ran down the slope of the roof to the gutter. There is also the accumulation of icicles on the end of the gutter, demonstrating that the water froze as it was running off the roof. The formation of icicles in general is a natural process of melting snow, but it can also be detrimental to the surrounding area, as exemplified by Fig. 9.  Figure 9: Tree at the entrance of the Italian Cultural Center, over the course of two weeks This tree was placed as an ornament next to the entrance of the Dante Alighieri Italian Cultural Center, completely ignoring that it was directly under the eave at the south-west of the building, which in general is prone to accumulating snow in the Boston region because all the nor'easters during the winter.

Right above it, a massive icicle started forming from the insolation, and most probably the wind made drops fall onto the tree below. The different directionalities of the icicles demonstrate the slow decline of the tree, resulting in it breaking (this can be deduced from the tree remaining bent even though the ice had melted by March 1). There is also the possibility that the directions of the icicles favored the directions of the branches, but this seems unlikely considering the position of the branches and the direction of the icicles. All in all, icicle formation is a great indicator for the natural processes of heat absorption, insolation or improper insulation.

Figure 9: Tree at the entrance of the Italian Cultural Center, over the course of two weeks This tree was placed as an ornament next to the entrance of the Dante Alighieri Italian Cultural Center, completely ignoring that it was directly under the eave at the south-west of the building, which in general is prone to accumulating snow in the Boston region because all the nor'easters during the winter.

Right above it, a massive icicle started forming from the insolation, and most probably the wind made drops fall onto the tree below. The different directionalities of the icicles demonstrate the slow decline of the tree, resulting in it breaking (this can be deduced from the tree remaining bent even though the ice had melted by March 1). There is also the possibility that the directions of the icicles favored the directions of the branches, but this seems unlikely considering the position of the branches and the direction of the icicles. All in all, icicle formation is a great indicator for the natural processes of heat absorption, insolation or improper insulation.

In fact, trees are not only great indications of the presence of sunlight, but also of the quality of soil in an area. Trees in general need sunlight, water, and aerated soil, to get the necessary nutriments. In fact, as is said in Granite Gardens, “The density of city soils is one of the primary reasons for the demise of trees in city parks and streets, and one of the least recognized.” One of the reasons for the high density of soil is the amount of pressure surrounding buildings, and to a certain case pedestrians too if walking directly onto the soil, put on the land. This deterioration of quality of soil can be visible throughout the city, if one area was more heavily industrialized than another, but also in close proximity. For example, on Fig. 10, the difference between the trees is clearly visible. One can assume that the cause for change is indeed the soil and not the fact that the trees were planted at different times because new buildings generally tend to plant their outside accoutrements at the same time. On the left hand side, the tree is a lot taller and fuller than the tree on the right hand side: the clear difference between the two is the size of the plots of soil. On the right there was only a thin plot of soil whereas on the left the larger area allowed for more water and aeration to go through. Another example of trees being manipulated by their environment can be seen on Fig. 11: on the north facing side, the tree is growing much more lush and outwards whereas the south facing side is growing upwards. This can be explained by the need for sunlight that all trees have: reaching upwards would give it access to the sun, which at its base is blocked by the neighboring building. Upon close inspection, it was also clear that the tree had been trimmed to leave the power cables clear. This demonstrates the tug-of-war between the presence of Nature in the natural environment, and the space that is given for it to actually exist.

Figure 10: Along Hampshire St, different size of trees, where their heights are marked by orange bars (approx.). The right side is significantly smaller.

Figure 10: Along Hampshire St, different size of trees, where their heights are marked by orange bars (approx.). The right side is significantly smaller.

Figure 11: Also along Hampshire St, different forms of trees caused by the cardinal directions they face. The SW facing tree receives more sunlight, whereas the NE facing tree needs to reach upwards for it.

Figure 11: Also along Hampshire St, different forms of trees caused by the cardinal directions they face. The SW facing tree receives more sunlight, whereas the NE facing tree needs to reach upwards for it.

Thus, there is a plethora of natural processes taking place on this site, both being affected by the presence of human inhabitation and affecting it. It is much easier to think of the ground and how human habitation was built on it as part of Nature than the air that surrounds it, because of its intangible nature. However, this is one aspect that is easily overlooked and has caused great problems like poor air quality, which can be caused by distorting wind patterns. Thinking about the role of plants is also crucial, since every reform to make an area more habitable has included adding more greenery to the place. Wanting an end result is very different from actually leaving it the space to grow, and giving it the proper habitat, as demonstrated by the treatment of trees on this site in particular. One should also consider all of the processes that were missed because of the presence of snow distorting the perception of the area. For example, the bases of trees were difficult quantify and compare to the growth of the trees because these were covered by snow. Furthermore, to fully understand the scope of the processes taking place in an area, different times of day and season should be compared. Maybe the wildlife is migratory, and in the winter here it was simply not present. The next step to consider when analyzing this area is another key presence: humans. Looking at how human interaction have an effect on the neighborhood but also how these are changed by the space they inhabit will be extremely interesting. Living creatures of all sizes should be respected in the natural habitat where they exist, and urban planners and architects should take their daily needs more into consideration, as their projects become reality.

Footnotes:

1 Anne Spirn, The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design, (Basic Books, Sept. 10, 1985), pp. 5.

2 Spirn, The Granite Garden, p.xii.

3 James Elkins, How to Use Your Eyes, (Routledge: New York, NY, 2000), p.29.

4 Spirn, The Granite Garden, p.105.

Bibliography:

Anne Spirn, The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design, (Basic Books, Sept. 10, 1985), pp.xii, 5, 105.

James Elkins, How to Use Your Eyes, (Routledge: New York, NY, 2000), pp.29-30.

Image sources: All the images taken by the author unless otherwise noted.

Fig. 1: “Cambridge, MA.” Map. Google Maps. (Google, 2015)

Fig. 3: “Cambridge, MA.” Map. Google Maps. (Google, 2015)

Fig. 4: U.S. Geological Survey. Boston South, Massachusetts [map]. 1:25,000. (Washington D.C.: USGS, 1954) and Frentzel, George F. J., “Carte von dem Hafen und der Stad Boston”, Geographische Belustigen zur Erklarung der neuesten Weltgeschichte. Stuck 1. (Leipzig: J.C. Muller, 1776)