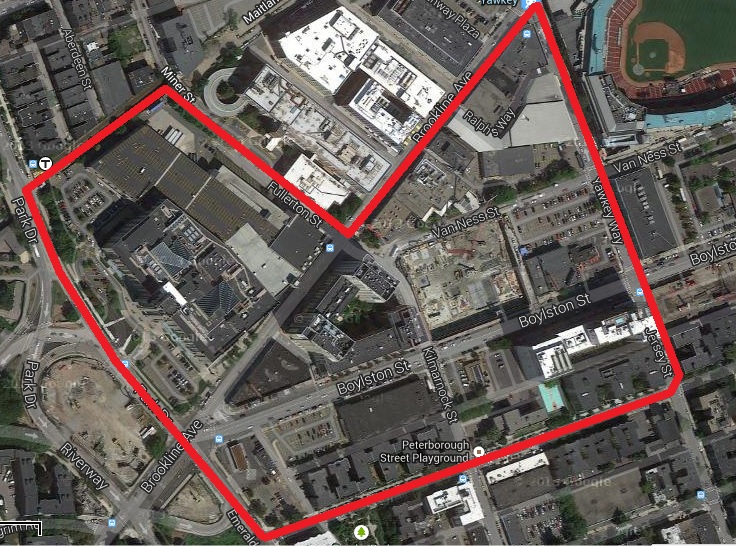

Fig 1. The demarcation of the site | Map data ©2013 Google, Sanborn, Cnes/Spot Image, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agency

Fig 1. The demarcation of the site | Map data ©2013 Google, Sanborn, Cnes/Spot Image, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agency

Despite the recent construction boom in Fenway, a surprising number of artifacts still remain. Some of the artifacts are in disrepair; others are thriving. The deciding factor in the condition of these artifacts is former land use. Not too surprisingly, functionally obsolete automotive-related structures fare least well, whereas housing and schooling are more resilient. In addition, some of the artifacts, like the Landmark Center, act as traces of larger phenomena and indicators of trends for the future. Artifacts from different time periods form distinct layers, but with recent development in Fenway, these layers are slowly being obliterated. One can only hypothesize about the implications down the road.

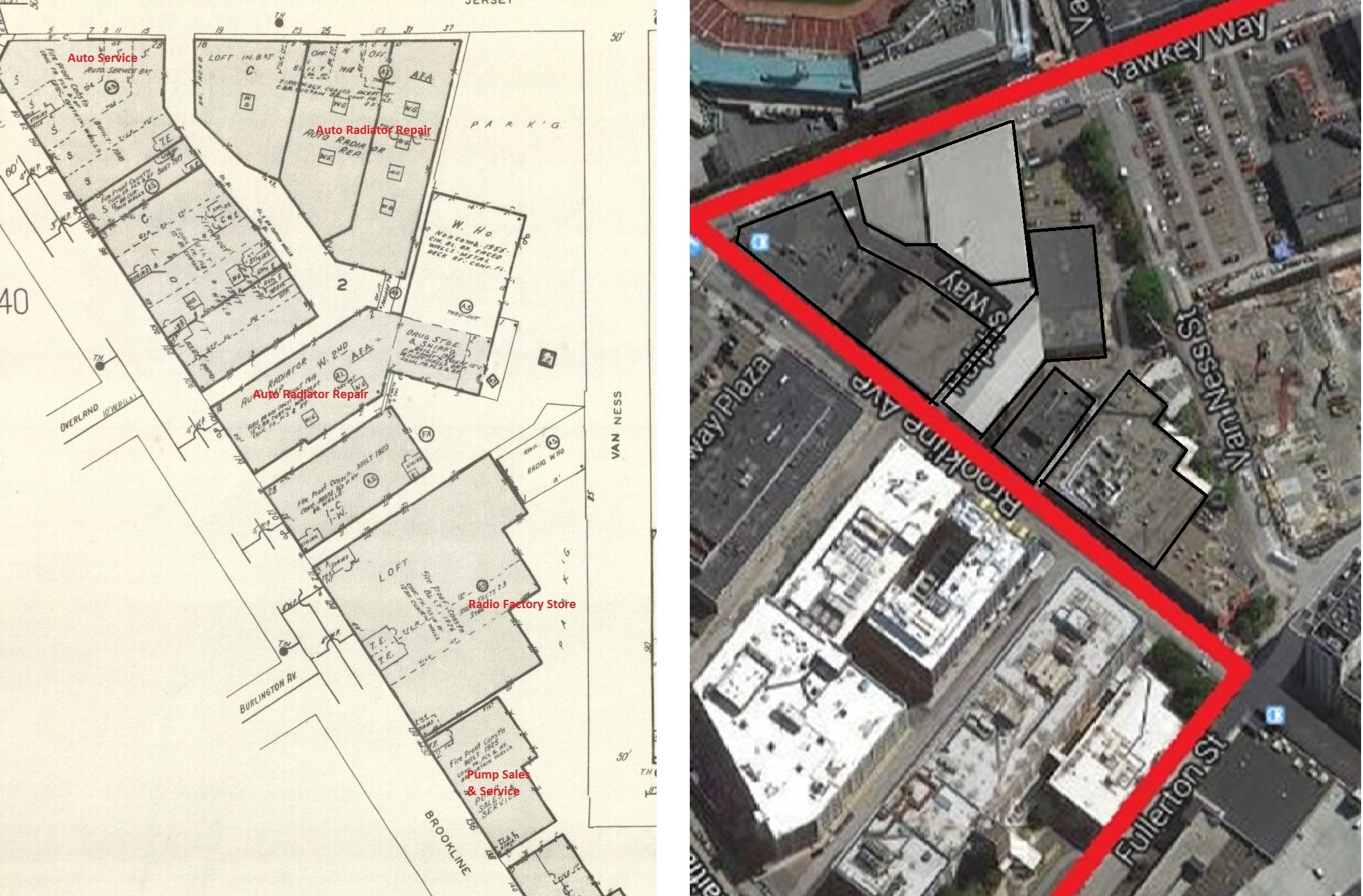

Remaining Eyesores and the Challenges of a One-Sided EconomyFor nearly two decades after the reclamation of its marshes, Fenway remained undeveloped due to an overwhelming investor ethos that emphasized speculation over construction. It was not until the arrival of the Red Sox in 1911 that serious development began: development which transformed Fenway into a bastion of the automotive service industry during the twentieth century. Today, a surplus of artifacts persists to commemorate the industry's former importance. Sanborn maps from the latter half of the twentieth century reveal a noticeable concentration of filling stations, tire services, pump sales and services, auto radiator shops, and general auto repair shops in the triangular parcel demarcated by Brookline Avenue, Jersey Street, and Van Ness Street. Virtually all of these buildings are still standing today, even if mostly vacant and dilapidated. Extensive litter, peeling facades, and large "FOR LEASE" banners posted in the filthy, upper story windows of the buildings show that the transition from an undiversified economy has not been easy. To be sure, some of the ground floor spaces are occupied - a bar, a cross-fit gym, a Tae Kwon Do "institute," a tiny pizza parlor. But even so, the remaining upper two floors remain unused. Walking down the block, it is hard to avoid feeling like the place has seen better times. Everything that meets the eye is the residue of bygone glory days.

Fig 2. Left: Building footprints in 1974. Right: Most recent building footprint according to Google Maps, with buildings outlined for better clarity. Notice the rentention of structures. | Sanborn Map Company, Incorporated. Boston, Mass.. Map. Pelham: Sanborn Map Company, Incorporated, 1974. From MIT Rotch Library, Vol 2N. Google.

Fig 2. Left: Building footprints in 1974. Right: Most recent building footprint according to Google Maps, with buildings outlined for better clarity. Notice the rentention of structures. | Sanborn Map Company, Incorporated. Boston, Mass.. Map. Pelham: Sanborn Map Company, Incorporated, 1974. From MIT Rotch Library, Vol 2N. Google.

Fig 4. Massive surface parking lots mean lucrative profits, but only during Red Sox games.

Fig 4. Massive surface parking lots mean lucrative profits, but only during Red Sox games.

Ironically, the phasing out of the automotive service industry has only ushered in another, different niche economy. While the seasonal influx of baseball fans has been an important economic stimulus to the area, it has also promoted a somewhat specialized, one-sided economy in the northernmost portion of the site - one perilously dependent on the sport for its viability. As most of them are vacant, the disheveled buildings adjacent to the ballpark lack any meaningful land use, aside from parking. During baseball season, these buildings along Brookline Avenue rent off their parking lots for exorbitant sums of money; I recently visited the area during a Red Sox game, and found the typical parking rate to be about $50. In short, the livelihood of the area immediately bordering Fenway Park Stadium hinges precariously upon providing parking.

Yet, livelihoods based solely on seasonal parking are hardly sustainable. It is reasonable to infer building vacancy and abandonment during offseason. Their crumbling veneers remain, but the buildings themselves serve no purpose. The artifacts of the automotive service industry have paved the way for the current trend of Red-Sox dependent seasonal utility.

Continuity through Time: Housing and SchoolingHowever, further south in the site, artifacts of a different kind exist. Fortunately, the prospects for this set of artifacts seem much more promising.

As discussed at length in the previous assignment, "Site through Time," much of Fenway languished undeveloped until the 1920s. Even after the arrival of the Red Sox, there was a time lag of roughly a decade before the complete revitalization of the real estate market. By the time the ballpark's economic stimulus was felt in full, a whole industry centered on the automobile had emerged. As elucidated in the prequel to this assignment, this industry matured very quickly, reaching its saturation point by the early 1950s. For the latter half of the twentieth century, little new development would occur. Modern aerial views of the area suggest the same can be said even for today.

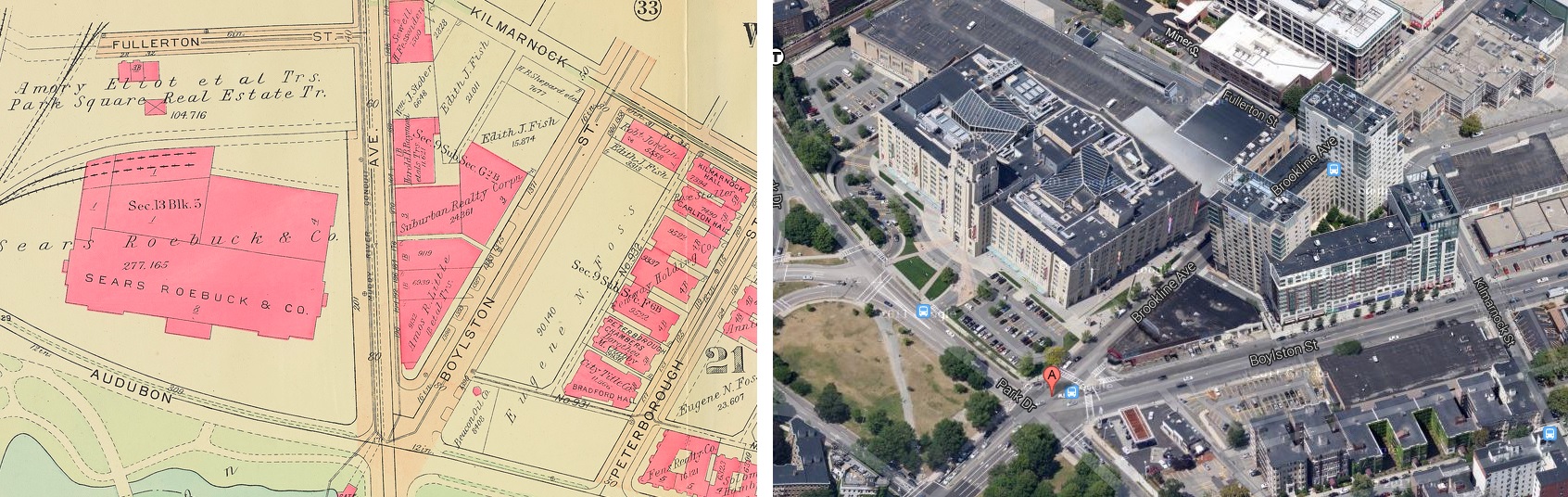

Fig 8. Left: Building footprint in 1928 Right: Building footprint now. The Landmark Center used to be the Sears Roebuck mail order store. The 7 apartment structures along Peterborough Street still stand today. The D'Angelo sandwich shop is housed in a building that dates well back.

Fig 8. Left: Building footprint in 1928 Right: Building footprint now. The Landmark Center used to be the Sears Roebuck mail order store. The 7 apartment structures along Peterborough Street still stand today. The D'Angelo sandwich shop is housed in a building that dates well back.

Yes, Fenway is in a period of flux, practically bordering upheaval. The newfound momentum of the past five years guarantees a radically different neighborhood a decade from now. But there still exist areas where developers have not moved in - old areas untouched and preserved from the early 1900s. For example, the earliest of multistory apartments along Peterborough Street date back to the 1912; the "newest" are from 1928 - hardly new at all. Nevertheless, these apartments remain intact and occupied today. The grounds are well-maintained, not derelict like the former auto repair shops near Fenway Park Stadium. The language of the landscape alluded to in Anne Spirn's work "The Language of Landscape," such as flourishing plant and animal life, suggests a peaceful coexistence between humanity and nature (1998, 11).

Similarly, the building that used to be Martin Milmore School still retains its educational function, albeit now as McKinley Preparatory High School. Bromley maps show that the schoolhouse was built in the 1930s, making it a fairly old establishment.

Why is it that these buildings built more than half a century ago are still flourishing, when the buildings immediately adjoining Fenway Park Stadium are not? Why is it that these buildings hardly seem to be artifacts of the past, when they indeed are? The answer is simple. The need for housing and schooling is timeless. Niche economies are almost never robust. Adaptive reuse of space, especially space once tailored to a specialized trade, is difficult.

Vestiges of the Past turned Indicators of the Future

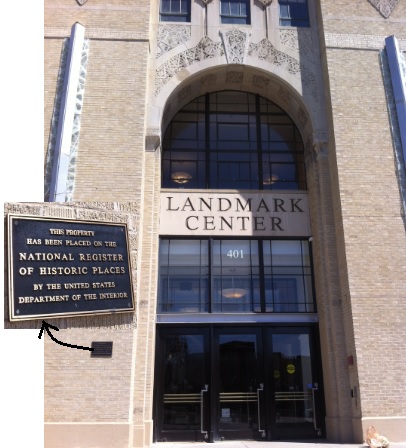

The present-day Landmark Center, at the intersection of Park Drive and Brookline Avenue, was formerly a Sears, Roebuck and Company Mail-Order and Retail Store. In fact, a brief comparison of a 1928 Bromley map with a modern aerial view of the site reveals a remarkably similar building footprint; the building's structural form appears to have been perfectly preserved since its inception nearly eight decades ago. Indeed, a plaque on the building's exterior vaunts the Landmark Center's special status on the National Register of Historic Places.

Fig 10. The main entrance to the Landmark Center. A plaque boasts the building's special historic status. The building is now certified Energy Star efficient, according to the logo at the bottom left of the door.

Fig 10. The main entrance to the Landmark Center. A plaque boasts the building's special historic status. The building is now certified Energy Star efficient, according to the logo at the bottom left of the door.However, the building has been repurposed in the meantime, from a mail-order warehouse into a retail and office complex. Originally owned and operated by Sears Roebuck, the building now houses many tenants, including major merchants like Bed, Bath, and Beyond, Staples, REI, Longhorn Steakhouse, and Regal Cinemas. The center also leases office space, a substantial portion of which is occupied by Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Massachusetts, Harvard Medical School, Harvard School of Public Health, and other healthcare-related ventures compelled by the close proximity to Longwood Medical and Academic Area. The Landmark Center's transformation portrays Fenway's ascent from a formerly industrial region into a hot consumer destination. The presence of major retailers in an almost century old building reveals how valuable and sought-after Fenway real estate has become. Similarly, the presence of healthcare organizations demonstrates Longwood Medical District's impact on redevelopment economics within the site.

The Landmark Center is an artifact of the past, in the strictest sense of the term: it has faithfully retained its original building footprint. However, the Art-Deco styled building can also be considered a trace of the mail-order phenomenon that gained traction in the late nineteenth, early twentieth century. Railroad expansion, American westward settlement, and an efficient postal system were congenial to the mail-order enterprise, but times would change (Sears Brands, LLC 2012). Sears Company would discontinue production of the general Big Book Catalog in 1993, in response to modern trends in retailing (Sears Brands, LLC 2012). As a former Sears Roebuck and Company mail-order store, the Landmark Center is the trace of a period when mail-order still dominated business models. Similarly, it follows that the Landmark Center can also serve as a trace of an economy heavily dependent on rail infrastructure.

Yet, the Landmark Center's didactic capacity extends beyond serving as both an artifact and trace; the building's prospects hint at larger trends that will dictate Fenway's future. Samuels and Associates, the current owner of the Landmark Center, intends a massive expansion for the limestone and brick building. The group hopes to demolish the existing parking garage in favor of several new towers that will house 550 residences, a 75,000 square feet Wegmans grocery store, and 125,000 square feet of shops, restaurants, and offices (Acitelli 2013). The Landmark Center is not Samuel and Associates' only project in the Fenway area. The firm's other neighborhood projects include Fenway Triangle Trilogy, 1330 Boylston Street, the currently under-construction Boylston West, and the recently approved and forthcoming The Point (Acitelli 2013).

Fig 12. The picture on the left was taken near the beginning of the semester, almost 3 months ago. The picture on the right shows the tremendous progress in Boylston West construction. The red banner says, "Ingenuity is Rising."

Fig 12. The picture on the left was taken near the beginning of the semester, almost 3 months ago. The picture on the right shows the tremendous progress in Boylston West construction. The red banner says, "Ingenuity is Rising."

The domineering presence of powerful real estate developers in the area, like Samuels and Associates, harkens back to the land commodification that characterized Fenway in the early twentieth century. The only difference is that developers are coming in and actually building; they are not waiting like the speculative investors of the past.

Developers Galore! Development without Displacement?

Samuels and Associates is not the only one to blame for the recent influx of luxury development in Fenway. Just a bit further down Boylston Street, tall cranes, porta potties, and bulldozers delimit territory for the soon-to-be Viridian. The $200 million, mixed-use development currently under construction is commissioned by the Abbey Group and will incorporate housing and retail. There is little to suggest the boom in new development will cease any time soon.

When one compares the median household income of the Fenway neighborhood to that of Boston, a striking disparity surfaces. While the median household income of Boston is $52,433, the median household income for Fenway is a paltry $32,509 (Department of Neighborhood Development 2014). So when one examines the cost of the luxury apartments entering the market, a conundrum arises; the average resident of Fenway would not be able to lease the $3,000-$4,000 single-bedroom apartment (The Fenway 2014). If anything, the projects appear to clear the way for an influx of white-collar workers capable of gentrifying the neighborhood.

Since local small businesses are particularly susceptible to the ravages of gentrification, I decided to make an impromptu stop into D'Angelo Sandwich Shop, located at the intersection of Brookline and Boylston, and talk with its manager. He explained that his lease will not be renewed past June of this year, as his landlord, Samuels and Associates, is planning to raze the building in favor of a new skyscraper development named The Point. (I will not disclose his name to protect his identity.) During the conversation, he admitted that he was not sure what would happen after the termination of his lease.

A similar fate awaits the Burger King joint located just down the street from D'Angelo. The fast food restaurant will be demolished to make way for another upscale mixed-use development, "1350 Boylston" (Grillo 2013). Intrigued to hear what its manager had to say about the upheaval besetting Fenway, I stopped by the Burger King as well. The site visit happened to coincide with a Red Sox game, and the manager and a college student employee were superintending the parking space rentals. When asked about his feelings, he coldly replied that such was life, and there was nothing he could do about it. At first glance, the problem in Fenway seems to be the exact opposite of the one facing the West Philadelphia Landscape Project. The people in Fenway are not landscape illiterate. They are not ashamed of "poor conditions" like in Mill Creek, because there are not any (Spirn 2005, 409). If anything, the people, as the Burger King manager demonstrates, recognize the imminent ascent of the neighborhood; they understand their land is valuable and esteemed by developers. But faced with the tide of gentrification, they are not much different than the Mill Creek residents. They too are helpless.

Fig 13. The yellow arrow indicates the Burger King joint that will be razed shortly. The two images were taken at the same time, and depict the Burger King from different vantage points. The Burer King is across the street from the under-construction Boylston West and next to the completed 1330 Boylston project.

Fig 13. The yellow arrow indicates the Burger King joint that will be razed shortly. The two images were taken at the same time, and depict the Burger King from different vantage points. The Burer King is across the street from the under-construction Boylston West and next to the completed 1330 Boylston project.

Fenway demonstrates that the impact of gentrification on the working class is not all rhetoric. Upscale new projects are being erected at the expense of small business tenants. The phenomenon in Fenway extends beyond indirect displacement from higher rents and higher taxes - it manifests in direct displacement through lease non-renewal and building demolition. Moreover, some of the small businesses, like Burger King. employ college students in the area. The eviction of these businesses will dispossess these individuals of their jobs, exacerbating their financial insecurity. The impact of gentrification trickles down.

In her work, The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History, Dolores Hayden stresses the necessity of grounding all political and spatial decisions in the history of the place's urban cultural landscape (Hayden 1995, 43). The implications of her statement for Fenway are particularly weighty. As the neighborhood rapidly gentrifies, a challenge will be to account for and appropriately accommodate the people whose livelihood will be jeopardized by the change, lest it become a homogeneous stronghold of the affluent and privileged.

With the rampant construction underway in Fenway, available real estate options will be copious. However, the developers undertaking revitalization projects in the neighborhood must ensure their efforts do not create an environment exclusive to the affluent. The heart of a city, after all, lies with the people who inhabit it; it would be difficult to imagine a vibrant community if there was no diversity.

All polemics aside, the bullish trend in the real estate market expresses itself in distinct layers within the site. Despite its new coat of beige paint, the D'Angelo Sandwich Shop is an obvious misfit against the stunning backdrop of the Fenway Triangle Trilogy. Something about the picture of the two standing next to each other is out of kilter; the rickety sandwich shop somehow lacks the same aura as the sleek, contemporary skyscraper. For better or worse, the razing of the sandwich shop for the $185 million The Point would make for a more seamless vista (Weiner Ventures LLC 2014).

Fig 14. The picture on the left was taken approximately three months before the one on the right. D'Angelo sandwich shop now has a new coat of paint, and a banner affixed to its facade: "These are the faces of Fenway. This is where we work. This is where we play. This is where we live." This is the same sign on other Samuels and Associates projects in the area, like Boylston West.

Fig 14. The picture on the left was taken approximately three months before the one on the right. D'Angelo sandwich shop now has a new coat of paint, and a banner affixed to its facade: "These are the faces of Fenway. This is where we work. This is where we play. This is where we live." This is the same sign on other Samuels and Associates projects in the area, like Boylston West. Similarly, the removal of the Burger King for the 196,400 square foot 1350 Boylston would produce a more homogeneous skyline (Grillo 2013). Sanborn maps suggest that the Burger King structure predates 1974. (There is a dearth of information available for the time between 1938 and 1974; the building appears on the 1974 map, but not the preceding 1938 map.)

Developers seem to find the rehabilitation of existing structures to not be worth their time or trouble; complete demolition emancipates space and options - because it allows them to more freely leverage the massive surrounding parking lots to their whims. Skanska, the New-Jersey based developer of 1350 Boylston, explains, "The project will continue the revitalization of this area of the Fenway neighborhood from surface parking lots and suburban style development to an urban area with a mix of uses" (Grillo 2013). In short, the various strata in the site are being effaced, bit by bit, with the razing of each old edifice.

Closing Remarks

Fenway still boasts a treasure trove of artifacts from the past. The outcroppings of new development notwithstanding, many of the buildings from the twentieth century remain intact, though in various states of grace. Some, like the residences and school along Peterborough Street, have not only survived but still retain their original utility today. Others, like the former automotive service shops near Fenway Park Stadium are dilapidated and largely vacant. The remarkable disparity in building conditions reveals how former land use is able to predestine the fate of a property several decades down the line; adaptive reuse of space may be problematic if a niche industry that once dictated building design becomes irrelevant.

As vestiges of the past, artifacts can shed light on historical national trends. But as present entities, they also possess the capacity to forecast future change. As a former Sears Roebuck mail-order store now undergoing expansion, the Landmark Center demonstrates how artifacts can sometimes serve as traces and trend harbingers. The power of artifacts is both palpable and meaningful.

Yet, in the midst of rapid gentrification and new development, Fenway's artifacts are being overhauled. With each razed building and skyscraper installment, the neighborhood becomes increasingly homogenous. Every demolition erodes another layer in Fenway's history. Furthermore, the supplanting of physical structures often coincides with displacement of small business, as seen in the D'Angelo sandwich shop and the Burger King.

Fig 16. This is the Google Map image that is displayed online today for the area where construction is currently underway for Boylston West. Google has not updated its map to reflect the construction. This makes us very lucky, because we can see what used to be there immediately preceding demolition.| Map data © 2013 Google, Sanborn, Cnes/Spot Image, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agency.

Fig 16. This is the Google Map image that is displayed online today for the area where construction is currently underway for Boylston West. Google has not updated its map to reflect the construction. This makes us very lucky, because we can see what used to be there immediately preceding demolition.| Map data © 2013 Google, Sanborn, Cnes/Spot Image, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agency.

Fig 17. A used to be a massive surface parking lot and abandoned warehouse. B used to be a mom and pop farm stand. Notice the architecture of the building highly resembles an auto repair/mechanic shop. C used to be a car wash. | Map data © 2013 Google, Sanborn, Cnes/Spot Image, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agency.

Fig 17. A used to be a massive surface parking lot and abandoned warehouse. B used to be a mom and pop farm stand. Notice the architecture of the building highly resembles an auto repair/mechanic shop. C used to be a car wash. | Map data © 2013 Google, Sanborn, Cnes/Spot Image, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, USDA Farm Service Agency.

Are current proceedings moving Fenway in the right direction? No one can say for sure. Yes, some small businesses are being displaced like the two fast food restaurants aforementioned. Yes, the new projects in the area are distinctively upper middle class. But you give some, you take some. At this time, housing along Peterborough Street appears intact and stable. It is plausible that its residents will not be affected, will not be displaced. Earlier maps show that Fenway was never too robust because of its niche automotive service economy. The site where the new Boylston West mixed-use development will eventually stand never thrived after the automotive service industry left. A car wash, a cleaner, an out-of-business mom and pop grocery shop: looking at the Google Maps street view, one gets the sense that these ventures were there "simply 'cause". Something needed to be there to fill the void, take up the space, prevent the block from being entirely vacant. Surface parking lots, garages, and functionally obsolete auto-related structure: all of these embodied wasted, underused space.

Is the incoming Boylston West a better alternative to squandered resources and a lack-luster economy? Is the price of a few displaced small businesses and unemployed individuals too high? In short, do the ends justify the means? I admit that, even after a semester, I'm still not sure. In the end, the dichotomy between good and bad is not clear.

Perhaps the common criticism against gentrification is not so applicable here. Site idiosyncrasies sometimes disqualify general convictions. The influx of capital, the introduction of energy-efficient, elegant buildings could be vindicated. But even this is speculation. Only time will tell.

Bibliography:

Acitelli, Tom. "Bring on the Apartments for Landmark Center!." Curbed Boston. http://boston.curbed.com/archives/2013/08/bring-on-the-apartments-for-landmark-center.php (accessed April 20, 2014).

Acitelli, Tom. "Our Updated Full Count of Construction Around Fenway." Curbed Boston. http://boston.curbed.com/archives/2013/10/our-updated-full-count-of-construction-around-fenway.php (accessed April 20, 2014).

Bellis, Mary. "Shopping Innovations." About.com Inventors. http://inventors.about.com/library/inventors/blshopping.htm (accessed April 20, 2014).

Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Atlas of the City of Boston: Boston Proper and Back Bay. Map. Philadelphia: G.W. Bromley and Company, 1928. https://www.flickr.com/photos/mastatelibrary/sets/72157634974482238 (accessed March 24, 2014).

Department of Neighborhood Development. "Fenway/Kenmore Data Profile. " https://www.cityofboston.gov/Images_Documents/Fenway-Kenmore_Planning_District_Profile%20_tcm3-12990.pdf (accessed April 15, 2014).

Grillo, Thomas. "Whopper of a Tower Planned for Fenway Burger King ." Boston Business Journal. http://www.bizjournals.com/boston/real_estate/2013/07/whopper-of-a-plan-for-burger-king.html (accessed April 20, 2014).

Hayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995.

"Landmark Center." Map. Google Maps, Cnes/Spot Image, DigitalGlobe, MassGIS, Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOEA, Sanborn, USDA Farm Service Agency. Imagery Aug 25, 2013. Google, 2013. Web.

Sanborn Map Company, Incorporated. Boston, Mass.. Map. Pelham: Sanborn Map Company, Incorporated, 1974. From MIT Rotch Library, Vol 2N.

Sears Brands, LLC. 2012. "History of the Sears Catalog." Last modified March 21. http://www.searsarchives.com/catalogs/history.htm.

Spirn, Anne Whiston. "Prologue: The Yellowwood and the Forgotten Creek." In The Language of Landscape. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998. 10-11.

Spirn, Anne Whiston. "Restoring Mill Creek: Landscape Literacy, Environmental Justice and City Planning and Design." Landscape Research 30, no. 3 (2005): 395-413. http://www.annewhistonspirn.com/pdf/SpirnMillCreek2005.pdf (accessed April 19, 2014).

"The Point." Weiner Ventures LLC. http://www.weinerventures.com/project/point (accessed April 20, 2014).

The Fenway. "Boston Luxury Apartments." View Available Apartments. http://www.fenwaytriangletrilogy.com/availableapartments (accessed April 21, 2014).