Copley Square: Traces and Trends

Keeping the Past in the Present

Copley Square: Traces, Layers & Trends

Our connections to the past are knowingly or unknowingly surrounding us. As we have discussed in previous papers, specifically in the Natural Processes assignment, there are forces that are uncontrollable despite our attempt to control our manicured urban environments. Despite many parts of my site being razed in order to create room for skyscraper office buildings and shopping centers, the traces of the past intentionally and unintentionally still remain. A trend on my site is the synthetic connection to the past, which stems from Bostonian’s interest and pride in reconnecting to Boston’s rich history. This reconnection to the past can be seen in the Copley Square area on varied scales: from buildings’ architectural style, the adjusted programming within buildings, and memorializing Bostonians and the Boston Marathon. Despite efforts to modernize the past, traces of the unaltered-past seep through in areas that are out of the public’s focus. An additional trend is the influence of transportation on the site. From streetcars to railroads to automobiles my site has been defined by the transportation that allows people to visit the site, since it is largely non-residential area. The current use infrastructure of transportation continues to influence as well as reveal the past of the Copley Square site. The area’s intention to revere the perceived past is prevalent, nonetheless the traces and artifacts of the true past can still be found.

Preserving the Past

Copley Square's Intentions

Over time the intentions of the area have altered. The land initially was developed to serve as a metropolis[1]: a cultural and academic hub of Boston. The MFA, MIT, and the natural history museum were these first pillars that intended to transform this area into a center of innovation. However, as these institutions grew and the land prices did as well[2], each institution decided to move where it could prosper in a less cramped environment.

The theme that stood out to me the most in the Copley Square area is the preservation of the past. Boston, as one of America’s oldest cities, is proud of its historical past. This theme, however, is not unique to Boston and Copley Square; as Kevin Lynch remarks in What Time is This Place?, “A new kind of urban preservation is emerging in the 1990s in community based public history, architectural preservation focusing on vernacular buildings, landscape preservation and commemorative public art.” The ‘urban preservation’ is a trend I would expect to continue to be prevalent on my site.

The theme that stood out to me the most in the Copley Square area is the preservation of the past. Boston, as one of America’s oldest cities, is proud of its historical past. This theme, however, is not unique to Boston and Copley Square; as Kevin Lynch remarks in What Time is This Place?, “A new kind of urban preservation is emerging in the 1990s in community based public history, architectural preservation focusing on vernacular buildings, landscape preservation and commemorative public art (228).” The ‘urban preservation’ is a trend I would expect to continue to be prevalent on my site.

Preserving the Past- Architectural Scale

The architectural preservation is prevalent through out my site. The buildings are the most notable artifacts of the Copley area: the Hancock Tower and Berkeley Building are significant members of Boston’s skyline and Trinity Church is renown as was selected as one of the ten most significant buildings in the United States by the AIA in 1885-1886. [4]

Figure 1: Image of Trinity Church and its reflection in the Hancock Tower. The tower also reflects the sky, which allows it to blend in and appear more airy.

Trinity Church’s Neo-Romanesque style is the focal point of Copley Square. It was taken into account when designing the new Hancock Tower. Bostonians were concerned that the looming skyscraper would cast a shadow on the beloved and culturally significant church. In order to reduce these effects the tower adopted a blue-tinted mirror-paneled minimalistic façade. This façade now reflects historical buildings in the area, contributing to and not diminishing their impact on the area. [5] In addition to its reflective nature, the façade’s blue-tint decreases its imposing presence because the blue is meant to mimic the sky and evoke the sense of the openness. Thus, despite the tower’s modern style, its presence accentuates the historic buildings in the area rather than feel iconoclastic.

Figure 2: Another angle of Trinity Church (from Copley Square) reflected in the Hancock Tower. This image accentuates the blue-tint of the façade and it’s minimized contrast with the sky.

Figure 2: Another angle of Trinity Church (from Copley Square) reflected in the Hancock Tower. This image accentuates the blue-tint of the façade and it’s minimized contrast with the sky.

Another building that is influenced by the addition of the Hancock Tower in the 1970s is the Berkeley Building. Besides losing its name and being designated as the ‘Old John Hancock Building,’ it also lost its significance as the second tallest tower in Boston and became cast in the shadow of the Hancock Tower [6] (see figure 3 below). The Berkeley Building despite its construction in the 1940s pays homage to the past. Specifically its column façade is a nod to ancient Greek architecture and a more classical style (See figure 4 below). Although the style is not specific to Boston’s past, it still ties into the theme of wanting to connect to the past.

Figure 3: Shown on the left the Hancock Tower reflecting the buildings in the area and the Berkeley Building standing to its right.

Figure 4: On the right, is a closer image of the Berkeley accentuating its segmented façade (columned section, and a single level partitioned from the upper levels).

Figure 4: On the right, is a closer image of the Berkeley accentuating its segmented façade (columned section, and a single level partitioned from the upper levels).

Preserving the Past-- Adapted Use Buildings

In addition to reflecting the past via architectural styles, there are traces on certain buildings in my site that reflect their past use. The first example is of this is on the backside of the brick buildings that are accessed via an alleyway between Stanhope St. and Stuart St (See figures 5-8 below). A majority of my site is stylized into a pseudo-historic mold, but in this hidden alley way (see figure 12 below) the layers of time due to changing ownership exist. A reason why these buildings have stood the test of time as brick buildings while many other buildings in the area have been rebuilt is because the Bay State Brick Co. owned them. The company may have had some influence in keeping these brick structures. On another note, a reason these buildings may not have been rebuilt into larger office buildings, which is a trend of my site, is because they exist in a non-standard shape site (See image 9 below). This awkward shape is due to the merging of the Back Bay and South End grids, which is why it was an ideal location to place the Railroad Tracks when the R&R companies were developing and unappealing as high rise office space.

Figure 5:The alleyway between Stanhope and Stuart Street’s desolate façade has the remains of painted advertisements. This displays the trace of a time period when this street was in use and could attract pedestrians to stop in.

Figure 5:The alleyway between Stanhope and Stuart Street’s desolate façade has the remains of painted advertisements. This displays the trace of a time period when this street was in use and could attract pedestrians to stop in.

Figure 6: This image is of a brick façade that has adapted over time. The difference in pattern and shading is visible in sections that used to be doors or windows, which have now been covered.

Figure 6: This image is of a brick façade that has adapted over time. The difference in pattern and shading is visible in sections that used to be doors or windows, which have now been covered.

Figure 7 & 8:More views of the residue of another use on the backs of buildings on Stanhope Street.

Figure 7 & 8:More views of the residue of another use on the backs of buildings on Stanhope Street.

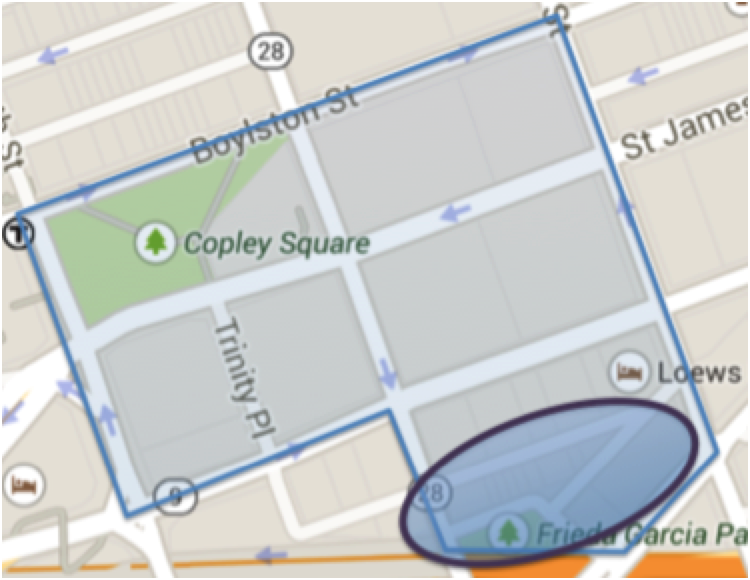

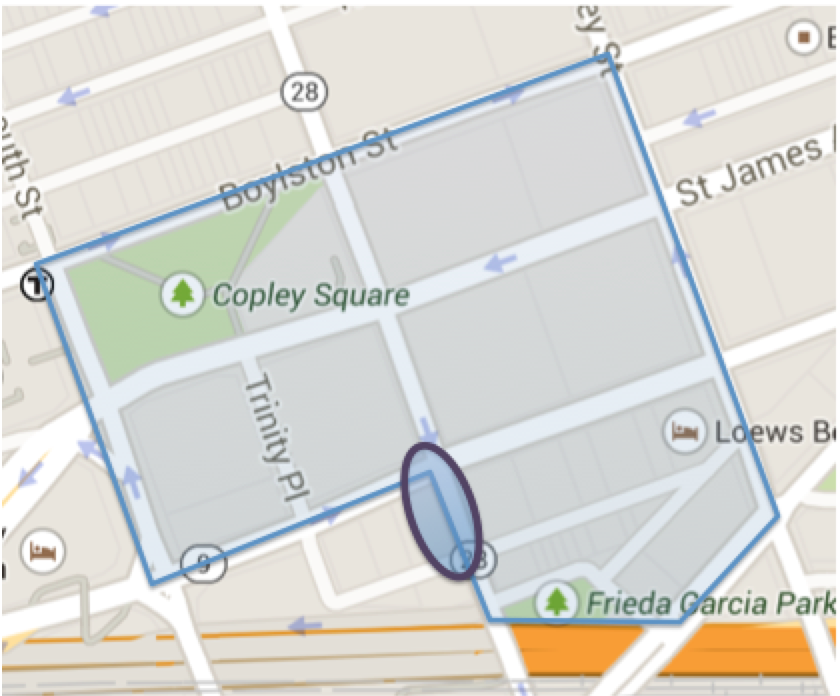

Figure 9: The circled section of the map of my site (which outlined in blue) is the area where the brick buildings still stand. The unnamed street at the top of the circle is the alleyway which is largely unused except by delivery trucks.

Figure 9: The circled section of the map of my site (which outlined in blue) is the area where the brick buildings still stand. The unnamed street at the top of the circle is the alleyway which is largely unused except by delivery trucks.

Another site that shows traces of its past use is the Young Women’s Christian Association (see it location below in figure 10). It was constructed in 1927 and was newly renovated in 2005 to incorporate additional uses[7]. After the renovation it is still possible to see traces of the 1927 building. In figure 11 it is possible to see the original inscription from 1929 flanking the building’s Clarendon Street entrance and positioned next to it is an advertisement for the laundry service that now exists on the street level. This is only one of the many uses that now coexist with the YWCA in the Clarendon Building. From the street it is possible to see these layers on the façade of the building (see figure 12).

Figure 10:The location of the YWCA at the corner of Stuart St and Clarendon St.

Figure 10:The location of the YWCA at the corner of Stuart St and Clarendon St.

Figure 11: Depicts an enscribed sign praising the glory of god and the year of construction (1929) next to a sign advertisign the laudry service that now is located within the WYCA structure.

Figure 11: Depicts an enscribed sign praising the glory of god and the year of construction (1929) next to a sign advertisign the laudry service that now is located within the WYCA structure.

Figure 12: This image depicts various layers of the site. The original plaque of the Young Women’s Christian Association from 1929 remains under an “Eliminating Racism Empowering Women” sign that reflects the YWCA’s . These two signs are situated next to a hotel 140 awning. This image is one of the most ‘layered’ sites I have found on my site.

Figure 12: This image depicts various layers of the site. The original plaque of the Young Women’s Christian Association from 1929 remains under an “Eliminating Racism Empowering Women” sign that reflects the YWCA’s . These two signs are situated next to a hotel 140 awning. This image is one of the most ‘layered’ sites I have found on my site.

The final adapted use building in my site to highlight is the Loews hotel. It exists on the site of the old Police Department. The hotel has as John Maibach, the general manager, states, “embraced the history of the building.”[8] The façade of the building still dotes the “City of Boston Police Department” inscription and the seals of police department (see figure 13). Additionally, the hotel has named is restaurant and bar “Precinct Kitchen + Bar” as a reference to its past. Due to these actual and synthetic connections to the past“…hotel guests will undoubtedly depart with a clear record of the history engrained within the walls of this Bostonian building.”[9]

Figure 13: Façade of the Loews hotel with the frieze from the Boston Police Department, “City of Boston Police Department,” still intact. Within each set of windows is a Boston Police Department seal.

Figure 14: The entrance to the hotel’s bar “Precinct” from the street level. This name is a clear reference to the building’s past use.

Figure 14: The entrance to the hotel’s bar “Precinct” from the street level. This name is a clear reference to the building’s past use.

Preserving the Past- Detail Scale

On a smaller scale, another way the site references the past is through the details. Within the square, the lampposts benches and gates all have an old-timey feel with their iron aesthetics. The images below highlight the historic looking features on my site. Additionally, many of the buildings in the Square highlight their heritage by displaying their year of construction on plaques prominently. See images below of the plaques on Trinity Church and the Fairmont Copley Plaza Hotel. Likewise, within the square there are signs hanging with Copley Square rules that prominently displays 1883, the year of the Square’s creation. The prominence of these artifacts emphasizes the area’s attempt to recall the past.

Figure 15: This figure shows the square’s benches. They evoke the past through their style. The Zeuthen, David. “Bench on Copley Square.” December 1, 2005.

Figure 15: This figure shows the square’s benches. They evoke the past through their style. The Zeuthen, David. “Bench on Copley Square.” December 1, 2005.

Figure 16 & 17: Pictured above are the plaques of construction (1912) featured on the façade of the Fairmont Copley Plaza Hotel. These are only three of the plaques that are on the façade of the hotel. As you can see in figure 18 there are two identical plaques a mere two feet away from each other, but on different façades of the hotel—one facing Dartmouth Street and the other St. James Avenue. The importance of the presence of these plaques is such that they must be seen from every angle as well as at each entrance.

Figure 16 & 17: Pictured above are the plaques of construction (1912) featured on the façade of the Fairmont Copley Plaza Hotel. These are only three of the plaques that are on the façade of the hotel. As you can see in figure 18 there are two identical plaques a mere two feet away from each other, but on different façades of the hotel—one facing Dartmouth Street and the other St. James Avenue. The importance of the presence of these plaques is such that they must be seen from every angle as well as at each entrance.

Figure 18: The sign in Copley Square listing the area’s rules displays its year of creation (1883) more prominently than any of the rules. This contributes to the trend of wanting to connect itself to the past. Similarly to the Loews Hotel, the Copley Square Plaza connects itself to the history of the Square and boasts “though many decades have passed since The Plaza [its sister hotel in NYC] and The Copley Plaza opened, today’s visitor would have an experience very similar to visitors in 1912.” [10]

Figure 18: The sign in Copley Square listing the area’s rules displays its year of creation (1883) more prominently than any of the rules. This contributes to the trend of wanting to connect itself to the past. Similarly to the Loews Hotel, the Copley Square Plaza connects itself to the history of the Square and boasts “though many decades have passed since The Plaza [its sister hotel in NYC] and The Copley Plaza opened, today’s visitor would have an experience very similar to visitors in 1912.” [10]

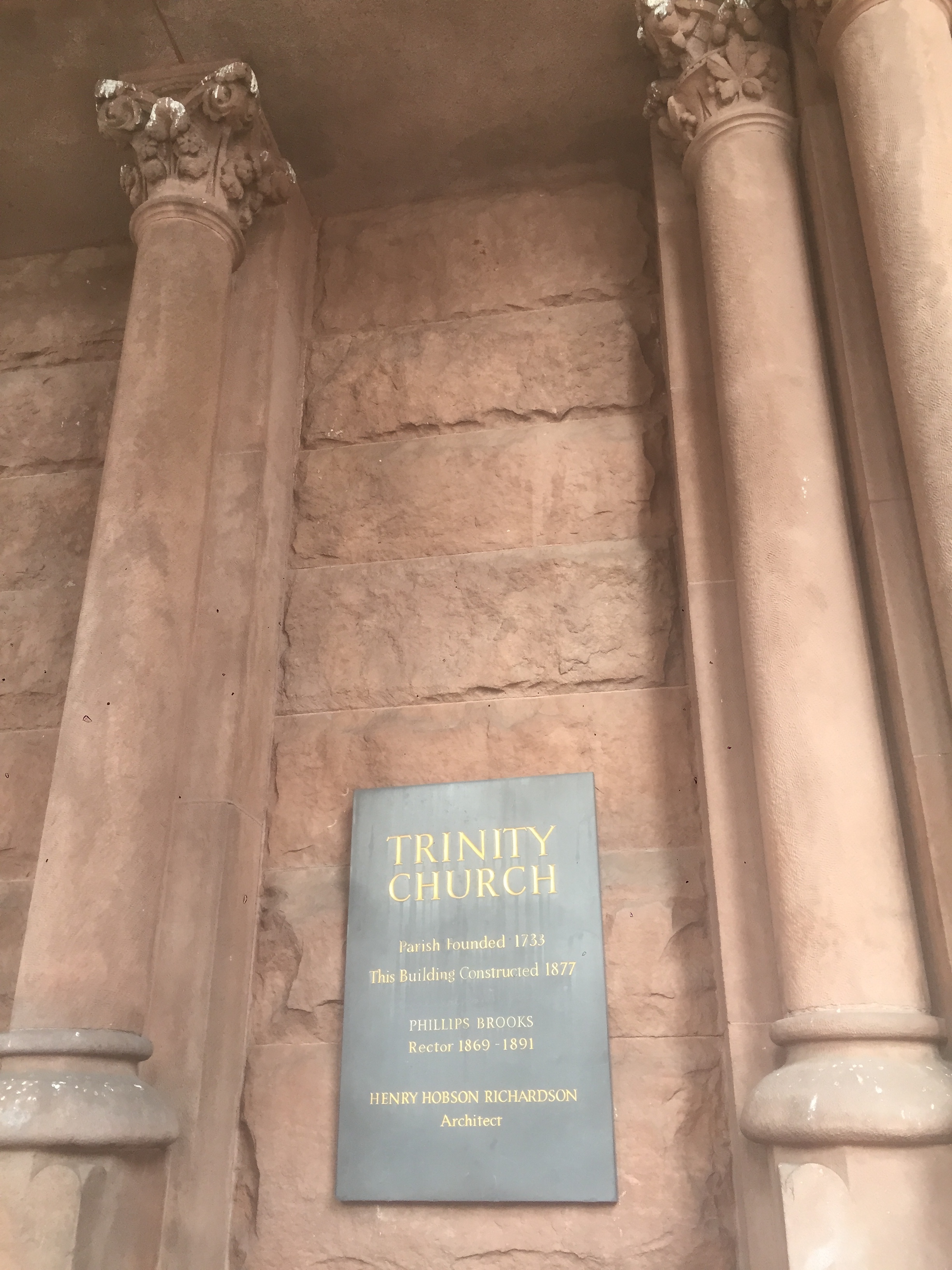

Figure 19: Like the Fairmont Copley Plaza Hotel, Trinity Church displays its parish’s creation and construction at its entrance. It does not place this plaque all over the façade of the church, as the Copley Plaza does, but the architectural style in itself is a tribute to the past.

Figure 19: Like the Fairmont Copley Plaza Hotel, Trinity Church displays its parish’s creation and construction at its entrance. It does not place this plaque all over the façade of the church, as the Copley Plaza does, but the architectural style in itself is a tribute to the past.

Figure 20 & 21: The historic style lamps on the Berkeley Building entrance.

Figure 20 & 21: The historic style lamps on the Berkeley Building entrance.

Transportation

Since the area directly surrounding Copley Square is largely non-residential, transportation is vital to the site’s success. The modes of transportation have varied from horses, to streetcars, to railroads and finally to the automobile. The contemporary technology supporting transportation spatially influences the land usage on my site. Since transportation infrastructure is a large land investment, the infrastructure for the various technologies have built upon the previous infrastructure.

The most relevant example of transportation technology building upon the past infrastructure is I-90. The imposing I-90 infrastructure is located where originally was the where the railroad tracks lay. The railroad intersection of Back Bay forces an awkward break in the grid. In 2005 the space was filled with a multipurpose solution, the Frieda Garcia Park. The park serves as a visual and spatial boundary between the interstate and the pedestrian commercial areas as well as serving as a green recreational space (See figures 22-24 below).

Figure 22-24: Images of Frieda Garcia Park— (22) The play structures (23) illustrates the break between the site and I-90 (24) the interface between the park and the pedestrian area on the south side of my site

Figure 22-24: Images of Frieda Garcia Park— (22) The play structures (23) illustrates the break between the site and I-90 (24) the interface between the park and the pedestrian area on the south side of my site

The highway is not always considered as space but Dolores Hayden remarks, “freeways connect dispersed locations of workplaces and dwellings, typical of contemporary working landscape. As interstate freeways carry automobiles speeding at 55 miles per hour, it becomes difficult to analyze the experience they provide …” [11] The Frieda Garcia Park not only is aesthetically pleasing to the pedestrians, but also it beautifies the freeway experience as commuters drive into Boston with its jovial colors and wall-sculptures.

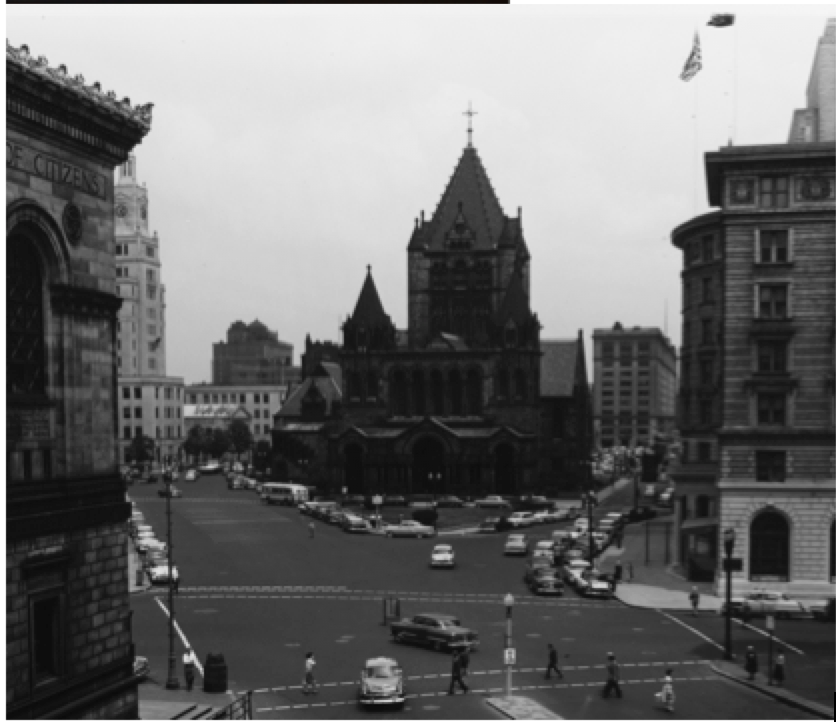

A trace of the past transportation infrastructure is seen directly in Copley Square, with the absence but influence of Huntington Avenue. Huntington Ave intersected the square and determined the plan of Trinity Church. Even though the Avenue does not exist any more its trace is still present because the plan of the church has not expanded further into the square. Below is an original image from the 1950s of the layout of Copley Square.

Figure 25: View of Trinity Church (Copley Square) with Huntington Avenue intersecting the site. Kepes, Gyorgy. Lynch, Kevin. Bichajian, Nishan.“Aerial View of Copley Square, 3rd Floor, 25 Huntington Avenue, 1:25-1:45pm.”1954-1959. MIT Libraries. “Perceptual Form of the City” collection.

Figure 25: View of Trinity Church (Copley Square) with Huntington Avenue intersecting the site. Kepes, Gyorgy. Lynch, Kevin. Bichajian, Nishan.“Aerial View of Copley Square, 3rd Floor, 25 Huntington Avenue, 1:25-1:45pm.”1954-1959. MIT Libraries. “Perceptual Form of the City” collection.

Boston Marathon

A trend that has already been touched upon is Bostonian’s pride in their city. I have discussed their pride in a historical context, but another thing Boston is proud of is its marathon—an entire day, Patriot’s Day, is even dedicated to cheering on the runners. The Boston Marathon’s finish line is located on Boylston Street in front of the Boston Public Library, leading into Copley Square. The finish was established in 1900, for the third BAA marathon, and has remained there ever since. Marking the centennial of the marathon, a commemorative memorial was constructed on the Boylston side of the square (see Figure 27). The memorial depicts the marathon’s route, the BAA unicorn and the inscription “One equal temper of heroic hearts; Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will; To strive, to seek to find and not to yield. – Tennyson. ‘Ulysses’”

Figure 27: The Boston Marahon Centennial Memorial. Located along Boylston Street in Copley Square.

Figure 27: The Boston Marahon Centennial Memorial. Located along Boylston Street in Copley Square.

The strength represented by the marathon memorial has become even more meaningful in the wake of the tragic bombings at the finish line in 2013. The bombings have drawn even more attention and Bostonian pride to the marathon. Since the 2015 marathon has just occurred, there are still many traces of the marathon’s presence in the square in addition to the memorial. Storefronts have painted their windows with motivational messages, billboards advertise the marathon, and many of the flowerbeds in the area tout blue and yellow flowers commemorating the 2014 marathon.

Figures 28-30: Some of the many advertisements and decorations featuring the Boston Marathon within and surrounding Copley Square

Figures 28-30: Some of the many advertisements and decorations featuring the Boston Marathon within and surrounding Copley Square

Figure 31: A view of Copley Square the day following the marathon. The exit sign directing runners towards the exit has yet to be removed.

Memorializing the Past

Copley Square, developed in 1883, was named after the American painter John Copley (See figure 32 below). This dedication reflects Boston’s intention of creating a burgeoning culturally aware area. When Back Bay was established as a residential area, the churches and institutions that were attractive to the elite Bostonians began to cluster in this area, which is on the periphery of Back Bay and the South End. An emphasis on culture and academia continues to be developed in the area; however, there has been a shift to cater towards tourism, commercialism, and office space.

Figure 32: Statue of John Singleton Copley in Copley Square. The inscription reads: “John Singleton Copley/ 1739-1815/ Boston and London/ American Portrait Painter/ Member Royal Academy of Art.” Copley was a famous artist from the colonial era. The statue depicts John holding paintbrushes. The dedication of the square to him highlights the trend of Boston’s cultural preservation and adulation of Boston’s past.

Figure 32: Statue of John Singleton Copley in Copley Square. The inscription reads: “John Singleton Copley/ 1739-1815/ Boston and London/ American Portrait Painter/ Member Royal Academy of Art.” Copley was a famous artist from the colonial era. The statue depicts John holding paintbrushes. The dedication of the square to him highlights the trend of Boston’s cultural preservation and adulation of Boston’s past.

The most surprising, but telling, memorial I stumbled upon in the square is for the Poet Khalil Gibran. The stone memorial stands facing the Boston Public Library. Khalil Gibran educated himself in the Boston Public Library. He used the area as it was intended, to grow culturally and intellectually. I find his memorial inspirational; it serves as a reminder that even in our modern lives where we can get caught up in work and commercialism that education is and should be accessible to all.

Figure 33: “Kahil Gibran Memorial from side, Copley Square- Boston.” Massachusetts Office of Transport. July 20, 2012. [12]

Figure 33: “Kahil Gibran Memorial from side, Copley Square- Boston.” Massachusetts Office of Transport. July 20, 2012. [12]

Conclusion

The Copley Square site serves as a reminder of Boston’s cultural and historical contributions. It strives to emphasize the past as a culturally important area. An opposing view to this ‘historical preservation’ comes from Dolores Hayden. She notes in Power of Place,

“Places also suffer from clumsy attempts to market them for commercial purpose: … developed ‘themes’ to make them more attractive to tourists, the places become caricatures of themselves.’” [13]

Hayden suggests using clunky themes is a ploy to create tourism and is not a genuine representation of the past. To a certain extend this is a trend of Copley Square, that it has turned towards revitalizing the ‘past’ and towards commercialism and tourism. However, the Bostonian pride and interest in institutional success extends beyond a solely tourism. Looking to the future, I expect to see continued preservation of the past while adopting modern trends.

[1] Haque, Ruiz. "Copley Square: Realizing its potential." 1984. MIT Press.

[2] ibid.

[3] Lynch, Kevin. “What Time is This Place?” 228.

[4] “Architect’s Choice: The Top Ten Buildings in the U.S.” 1885. American Architect & Building News.

[5] Raez.

[6] Despite existing in the Hancock Tower’s shadow, the Berkeley Building remains conspicuous in the Boston skyline and is known for its weather beacon (and its poem: “Steady blue, clear view. Flashing blue, clouds due. Steady red, rain ahead. Flashing red, snow instead.”

[7] YWCA Boston Timeline. Web. http://www.ywcaboston.org/timeline/

[8] Dada, Samah. “Traces of the Past” Loews Magazine. Oct 24, 2014.

[9] Ibid.

[10] The Fairmont Copley Plaza History Book

[11] Hayden, Dolores.

[12] “Khalil Gibran Memorial from side, Copley Square- Boston.” Massachusetts Office of Transport. July 20, 2012.

[13] Hayden, Dolores. “Power of Place.” 26.