Boston and Cambridge are two of the oldest cities settled on the East coast of the United States. Walking through their streets can make one feel like a colonial puritan looking from old churches, to cobblestone streets, to embossed eighteenth century headstones. However, my site is in the unique position of being in such an old city, but only being about one hundred years old. Since it is entirely built on filled land, it was a blank slate right at a period of drastic change for all American cities. This allowed it to be receptive to those changes in a way that an old, built up part of the city could not. As a large piece of land under single ownership, it had the potential to display great change, which it did. My site had three phases of change: from newly filled land to a large municipal park, from green space to bustling industrial center, and from production hub to a birthplace of research, technology and innovation. These changes stand to echo shifting national ideals of the quality of the urban environment, the necessity to maximize national production and industrial operations, and the current technology and research boom. These changes affected all American cities, and they are reflected very clearly in my site as the site adapts to its new neighbor: MIT.

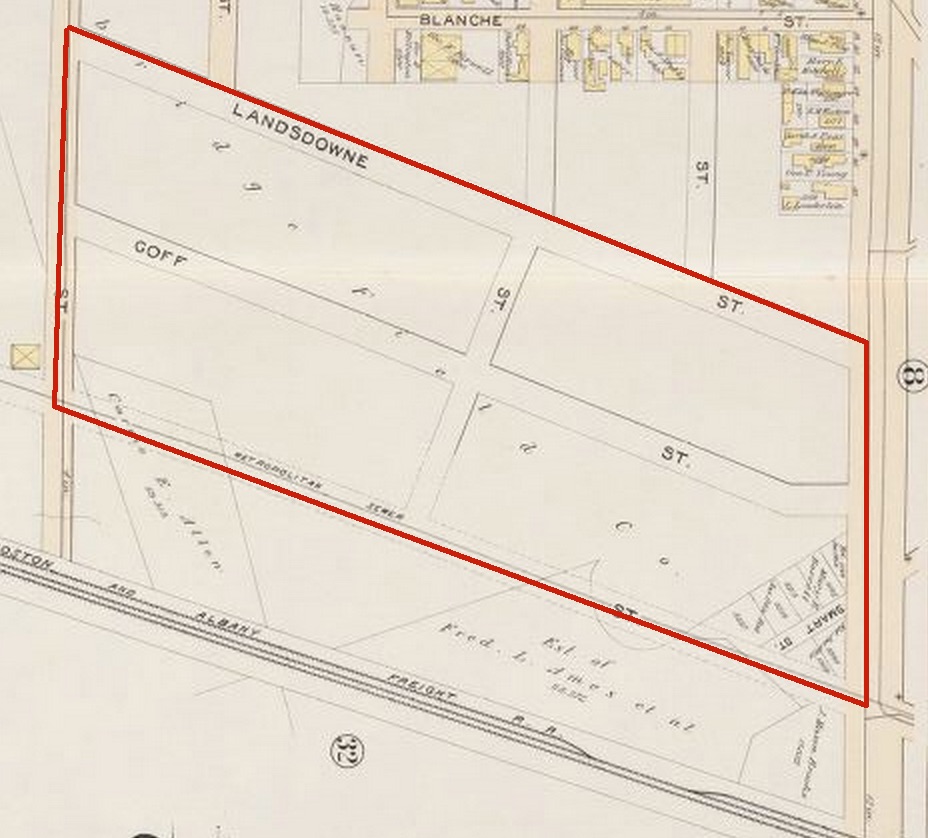

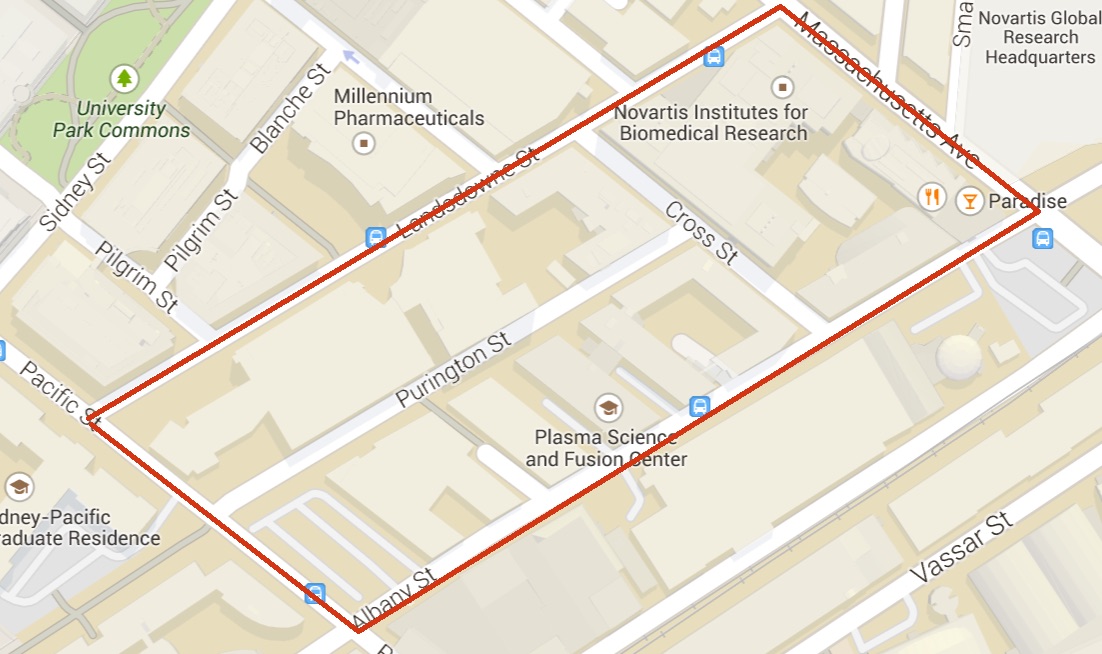

After examining many historical maps of my site from the 1890’s up to the present, I have chosen to alter the boundaries of my site. I did so not because the excluded areas of my site showed uninteresting changes, but rather because the area I have chosen to focus on is a well defined “mega block” that displays very clearly several waves of change. These changes point to changes on a larger scale that many American cities faced over time. This mega block spans from what is now Massachusetts Ave. to Pacific St., and from Landsdowne St. to Albany Street. These borders are quite close to the original borders I picked, which is interesting considering the historical evolution of my site. This mega block underwent most of its major changes as a unit and always retained its clear borders. Maybe something about the layout of the streets made me feel like these three large blocks went together, or maybe it was a random choice, but their unity points to their past and their evolution through the past century.

In its history, my site has displayed three major waves of change. The first of these was its conversion into Charles River Park and a large racetrack. After this, the land was sold into private ownership and it became highly industrial. This change started slowly but then within about a decade the site was packed with rail spurs, factories and other large buildings. Interestingly the prevailing industry in this area was in food manufacturing, and my site in particular took on a highly confectionary persona, as will be discussed later. The last major change in my site did not take place until the 2000’s when this industrial, food and sweets related area transformed into a complex of pharmaceutical companies and medical research institutions.

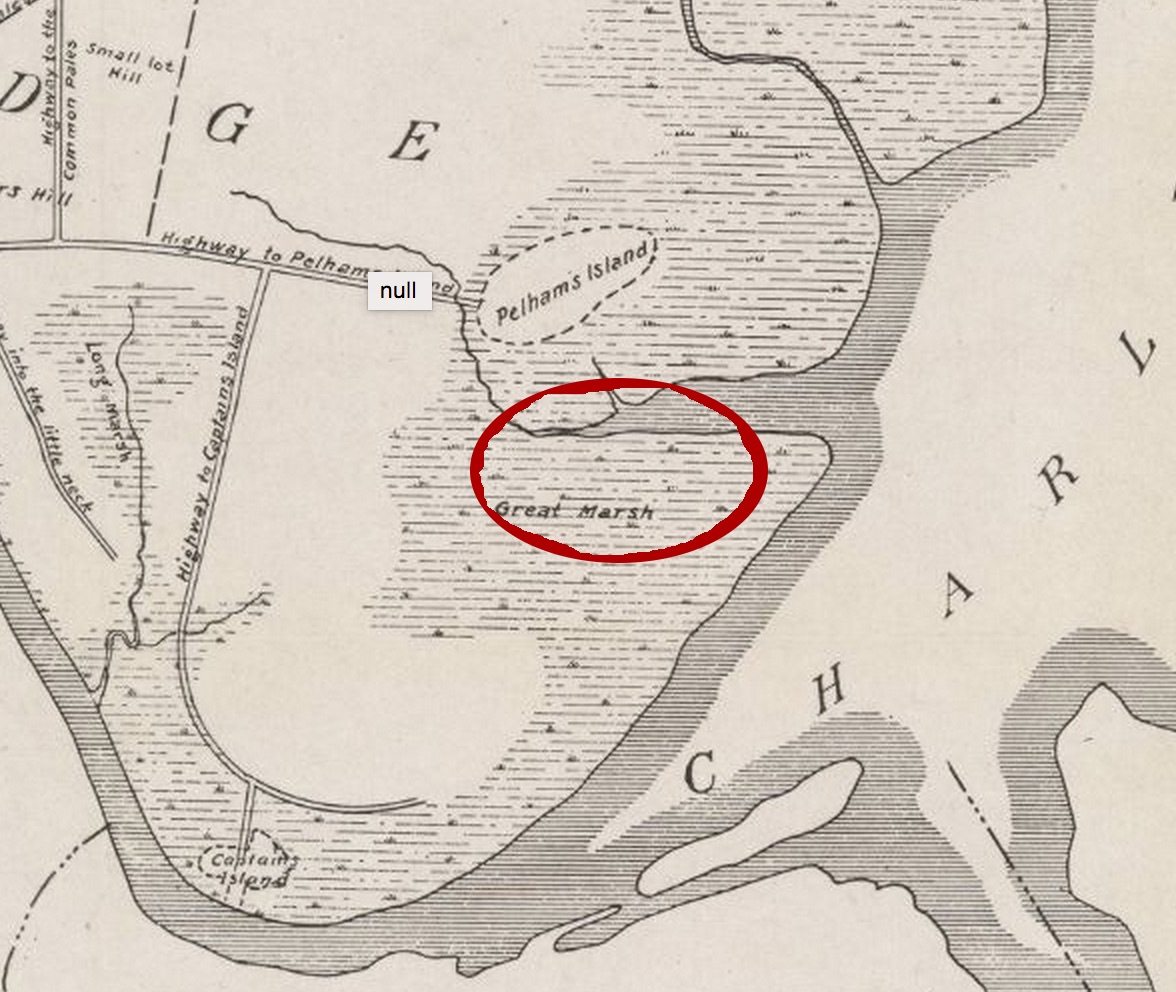

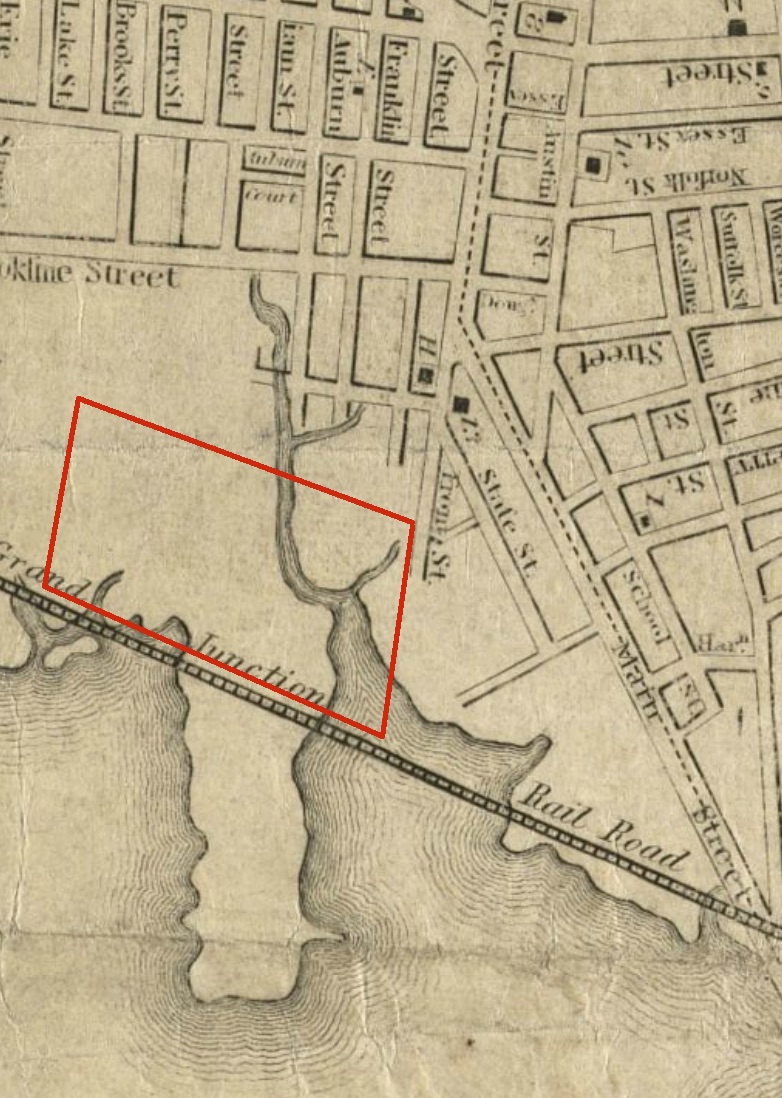

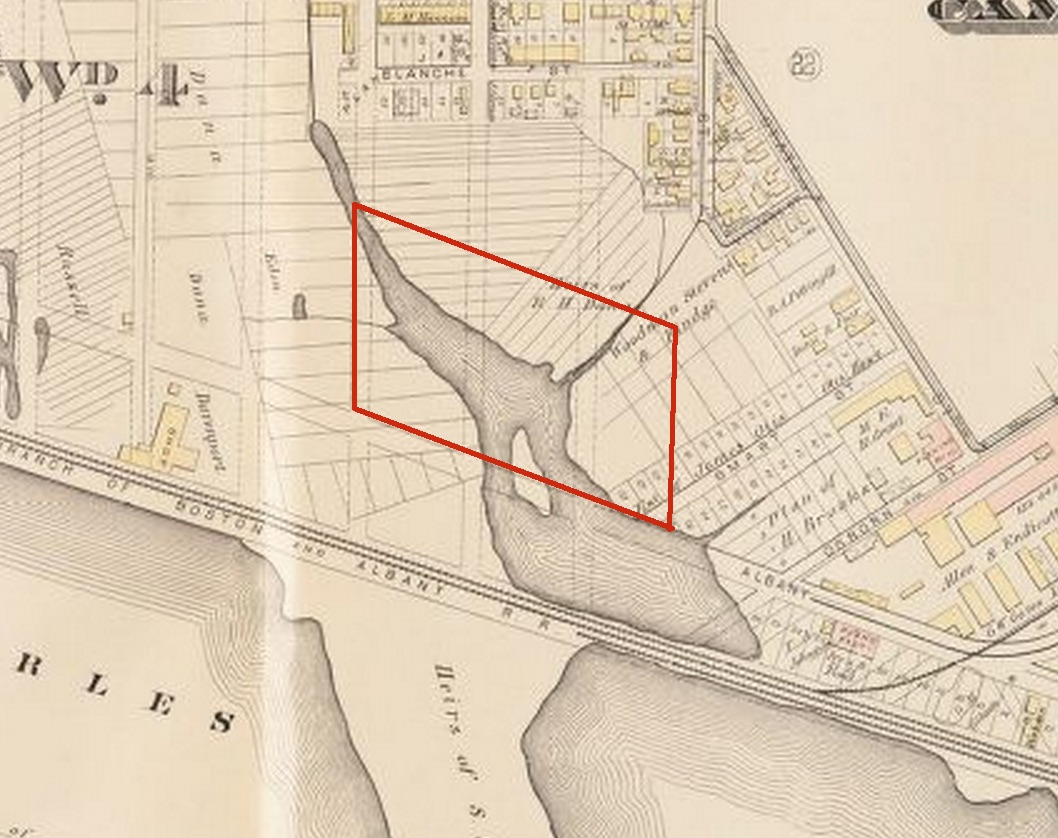

Before delving into the details of these major changes, I will first look at the earliest stages of development for my site, dating back to 1700, when my site did not yet exist. I have located my site to the best of my ability on the 1700 map of Cambridge Port based on the shape of the coastline (Map 1). It is located in the great marsh, just southwest of Pelham’s Island, at the mouth of a small stream flowing into an inlet. Although there are no significant details on that map, I was able to pinpoint my site by looking at subsequent maps. In the 1838 map it was easier to locate my site due to the street system in Cambridge Port (Map 2). At this time Mass. Ave. was visible on the map but it ended abruptly as soon as it hits the marshland. It was by far the largest street in Cambridge port at that time and it seems like it would have been beneficial for the area if it were to be extended into the marshland, and maybe even across the Charles River. In the 1857 map (Map 3), the location of my site can be determined yet again more accurately due to the construction of the railroad. The railroad snakes along the shore of the Charles, cutting across peninsulas and traversing inlets, and at the location where Mass. Ave would intersect the tracks (if it were fully built at this time) is my site. In this map, the beginning of Smart St. can also be seen, jutting out orthogonally from Main St. This street will come into play later in the development of my site, and its longstanding existence as shown by this early map may give reason for some of the interesting changes and anomalies in my site. By 1886, this street had been named Smart St. and although my site was still predominantly under water, a street grid pattern had been indicated on the map, suggesting intentions to fill the land (Map 4). The railroad line was labeled “Branch of Boston and Albany Railroad,” which is interesting since the street that currently parallels the tracks is called Albany Street.

Map 1: General area of site in marshland, Circa 1700

Map 1: General area of site in marshland, Circa 1700  Map 2: Rough location of site on inlet, beginnings of Mass. Ave. visible, Circa 1838

Map 2: Rough location of site on inlet, beginnings of Mass. Ave. visible, Circa 1838 1894 brought monumental change to my site. The land was filled and my site actually came into existence. The area north of my site was developed at this time, but my land was a blank slate, ready for growth. The land on which my site lay was under the ownership of the Cambridge Field Co., and had indications of future streets to be built as shown on the 1894 Bromley map (Map 5). Although almost the entire mega block was under ownership of the Cambridge Field Co., the southwest corner was highly divided. Smart St. cut through the block at this location and surrounding it were seven small properties under the separate ownership of Mary E. Bennet and Jas Otis Est. It is interesting that one corner of my site got so heavily divided early in its existence unlike the rest of my site, which remained under single ownership for three decades. For some reason it seemed like it was desirable to own property on Smart St. Maybe these property owners believed that Smart St. would become a highly trafficked street with many consumer shops, or maybe proximity to Mass. Ave. near the railroad tracks was highly desired.

Map 3: Site more precisely located next to rail line and along Mass. Ave., Circa 1857

Map 3: Site more precisely located next to rail line and along Mass. Ave., Circa 1857  Map 4: Site precisely located, potential street grid indicated, site still under water, Circa 1886

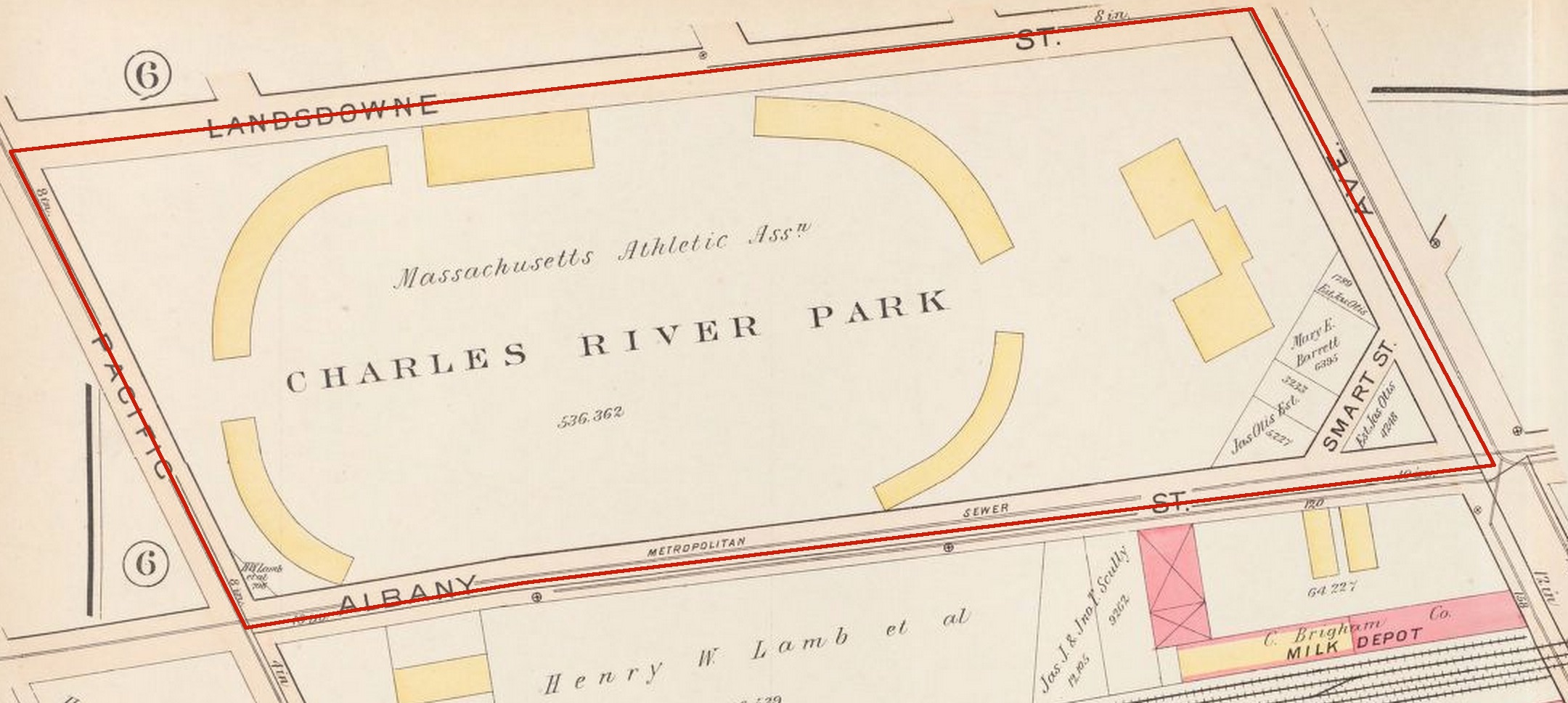

Map 4: Site precisely located, potential street grid indicated, site still under water, Circa 1886 Up until this point the changes I have been discussing have been subtle and I have been analyzing my site predominantly under a wide lens, noticing how it fits into its surrounding area. At the turn of the century, however, change started happening very quickly and my focus will be highly concentrated on my site. In 1903 the first major wave of change swept over my site. The Massachusetts Athletic Assn. acquired the land from the Cambridge Field Co. and built Charles River Park (Map6). This park consisted of a large track with a grandstand and bleachers and planted green space in its center and around its perimeter. It surprised me greatly when I first saw this park appear on the map. Firstly, I never would have guessed that in what is now such an industrial and commercial area, a park once existed. In addition to that surprise, I was puzzled why the Massachusetts Athletic Assn. did not acquire the land in the corner of my site where Smart St. cut through. This small triangle remained under separate ownership even though it seemed to awkwardly cut a corner off the park. At this point it seemed clear that that one corner of my site was highly desirable for some reason. Some of the answers regarding why and when Charles river park was built may have explanations in Kenneth Jackson’s book, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States.

Map 5: Site is now filled, potential street grid indicated, one large land parcel under single ownership, southeast corner under seperate ownership, Circa 1894

Map 5: Site is now filled, potential street grid indicated, one large land parcel under single ownership, southeast corner under seperate ownership, Circa 1894  Map 6: Charles River Park is built, Circa 1903

Map 6: Charles River Park is built, Circa 1903 In the late 1800’s there was a dramatic increase in immigration into the United States. Cambridge saw drastic population growth, tenant housing was created, and the Harvard Bridge was built to facilitate commutes from Cambridge to Boston. Cambridge was on its way to becoming a commuter city for Boston just like many towns in Long Island were for Manhattan. One specific town on Long Island is a case from which information may be garnered that may explain the construction of Charles River Park. Garden City is a town that was planned around the Long Island Rail Road line as an upscale commuter town. It was a highly planned community and one of the tactics its planner Alexander T. Stuart utilized was to create many green spaces and parks to raise the quality of the neighborhood and entice prospective property buyers. Since Cambridge Port was well on its way to becoming a large commuter suburb, as Jackson states in his chapter called The Transportation Revolution and the Erosion of the Walking City, maybe the municipal government was trying to follow a similar model as Stuart by introducing “planned greenery, which was supposed to enhance the appeal of the community”(Jackson 83). I went to school in Garden City for my whole life and I can attest to the improved urban experience by the addition of parks and can readily believe that Cambridge may have been trying to do something similar with the construction of the Charles River Park. During this same time, the Charles River Embankment Company was founded and started building parks and walking paths along the Charles River. This increased interest in improving urban form through recreational parks and green spaces stands to corroborate this theory.

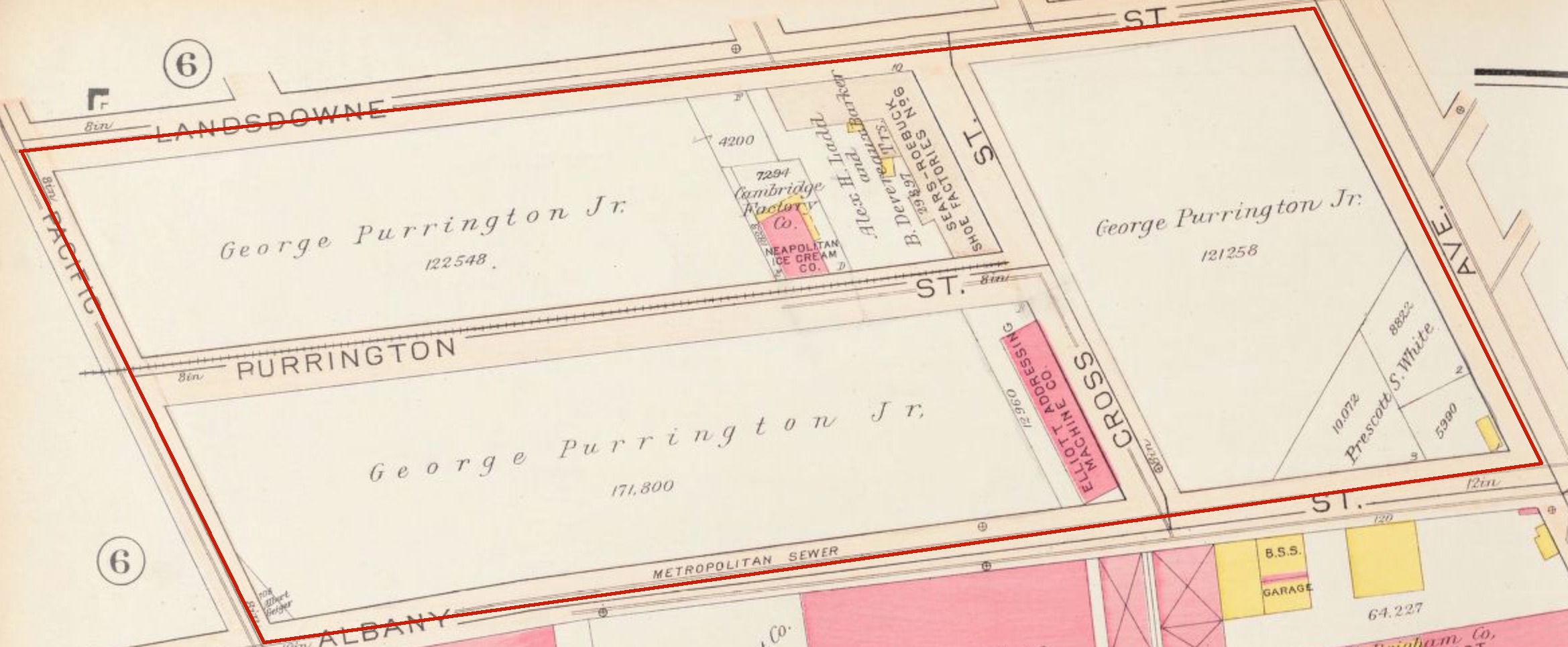

By 1916, the second major wave of change was beginning to take place on my site. A gentleman named George Purrington Jr. bought nearly the entire block from the Massachusetts Athletic Assn., excluding the small deviant corner, and subdivided it into three blocks (Map 7). He named the two dividing streets in this large block Purrington St. and Cross St., both of which exist in the same locations today. Purrington St. does not extend all the way into Mass. Ave., most likely to maximize the amount of available storefront space on Mass. Ave. This reaffirms the idea that that corner of the site remained highly coveted by its owners through my sites periods of change because storefront space on Mass. Ave. was considered highly valuable. In 1916, the ownership of the triangle changed and although the triangular property shape persisted, Smart St. was removed.

During this phase of change, my site began to take the shape it possesses today. It went from being an open green space to a blank canvas on which the quickly expanding industrial age was about to paint a network of mechanized factories, rail spurs, and manufacturing plants. This change echoed the change that was happening around the nation. Henry Ford had just invented the Model T, and the ideas of mechanization and mass production were spreading like wildfire. There was less need for parks and a rapidly growing need for industrial centers, which my site quickly became. Perhaps its proximity to the rail line allowed my site to so readily adapt to this industrial Revolution and become home to many industries that require the ability to rapidly distribute their products. The first brick buildings were built on my site at this time. The Elliott Addressing Machine Co. and the Neapolitan Ice Cream Co. sprang up, and between them was laid a rail spur giving the impression that the property owners had the intentions of creating even more large-scale industrial operations.

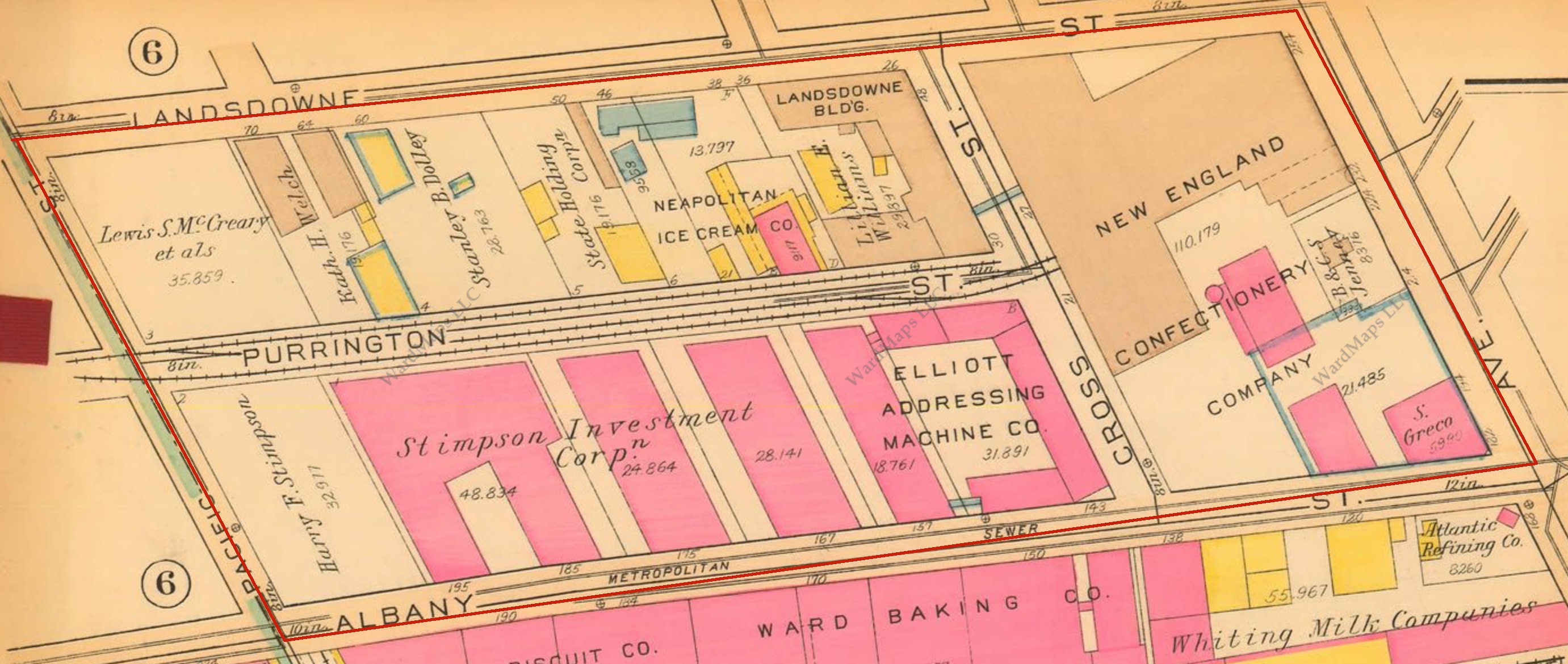

By the year 1930, this increase in industrial operations was clearly visible (Map 8). On the 1930 Bromley map of my site, the blocks look nearly as dense as they appear today. George Purrington sold all his land to a plethora of buyers and many small corporations were built. A huge complex of brick buildings were built and occupied by the Stimpson Investment Corp. and the New England Confectionery Company (NECCO) surfaced on Mass. Ave. NECCO clearly appeared to be the biggest player on my site and its presence persisted until after 1996. NECCO was not the only sweets-related company in the area however. The Neapolitan Ice Cream Company grew along side NECCO, and several other ice cream, dairy, and candy stores sprang up in the surrounding area, including Whiting Milk Companies, which is visible in the lower right hand corner of map 8.

Map 7: Land divided into three blocks, railroad spur built, first brick buildings appear on site, Circa 1916

Map 7: Land divided into three blocks, railroad spur built, first brick buildings appear on site, Circa 1916  Map 8: Massive increase in quantity and density of buildings, site begins to resemble current day, NECCO has established itself, Circa 1930

Map 8: Massive increase in quantity and density of buildings, site begins to resemble current day, NECCO has established itself, Circa 1930 This period from around 1916 to 1930 gave rise to the largest changes my site has seen. This is not surprising since during this time period massive changes occurred on both a local scale and on a national scale that would undoubtedly have a drastic impact on an industrial area like my site. Firstly the introduction of the Model T in 1908 and the subsequent increases in productivity through the production line in 1913 allowed for the size of industry to grow exponentially. My site saw the effects of the automobile directly with the addition of a filling station right in the center of NECCO on Mass. Ave., but it also saw it indirectly. Production rates had scaled up and the industry that took over my site was predominantly in the mass production of sweets. This may seem like a strange industry to grow so rapidly, but as Jackson writes, not only did the “quickening pace of the Industrial revolution” affect the oil, rail, and steel industries, sugar refinement also underwent a drastic change, and individuals like Henry O. Havemeyer took advantage of the increase in machine resources to expedite production and maximize profit. Locally, MIT had just moved from Boston to Cambridge, and since the institution was so heavily built on its relationship to real world industrial operations, its move sparked an increase in industrial growth in the area, that in turn increased MIT’s productivity and both fed off each other.

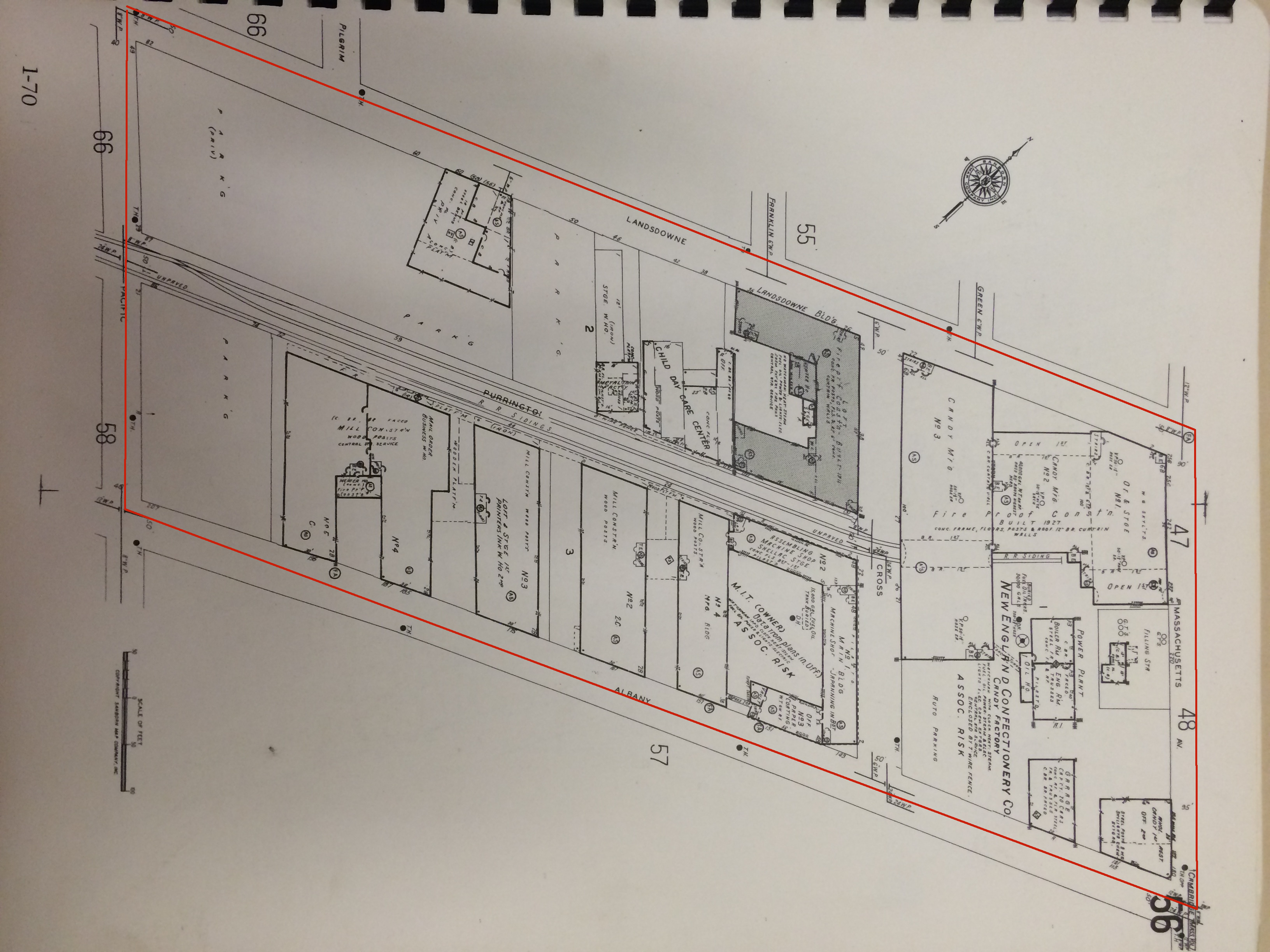

MIT continued to influence the evolution of my site well into the 1970’s (Map 9). The large Stimpson Investment Co. buildings changed ownership to Associated Risk, a MIT-owned company. Also, a child day care center was built on Landsdowne St. possibly to provide daycare services to the faculty and staff working at the rapidly expanding MIT. The large rail spurs remained in the middle of my site even though the rest of my site had clearly transitioned into the automobile era. There were many parking lots that squeezed themselves between buildings, and a service station and garage that sprang up. As Jackson explains in Crabgrass Frontier, the term “filling station” was coined for any gasoline pumping facility, and that by 1950 these stations became “one of the most widespread kinds of commercial buildings in the United States” (Jackson 256). With the growing popularity of the car and the notion of the “automobile suburb” it would seem like the rail line that for so long passed by my site would become obsolete. This was certainly the case with electric street trolleys, but since my site was entirely industrial for its whole history it did not see the effect of the disappearing street trolley that Jackson relates. It was also the case for many rail lines, but Jackson points out that rail transportation continued to persist and remain strong between several large American cities: New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and of course, Boston (Jackson 171).

My site did not see much change at all through the 1980’s and 90’s, and all the way until 1996, the site remained a large complex of confectionery and candy production facilities under control of NECCO. The third wave of change that swept across my site can be viewed as a direct influence of MIT’s move to Cambridge, as well as the product of a shifting focus in technological pursuits. In the 2000’s NECCO was finally moved from the site and in its place was built the Novartis Institute for Biomedical Research. Next-door, the Plasma Science and Fusion Center was built, and the entire area took on the feel of a tech startup environment (Map 10) . MIT had created a craze for research in the medical field and energy field, similar to the semiconductor craze that was started by Caltech in California. This craze had direct effects in MIT’s immediate environs, and has shaped the way the area looks today.

Cities are constantly growing and evolving to match the ideals of the people that live in them and of the nation in which they exist. Often an old city has trouble quickly responding to technological or ideological changes because it is highly developed and has historical value. This is where my site possesses its uniqueness. My site was a slab of open flat land right at a time when the American city started to explode through changes in structure of commuter suburbs, developments in transportation technology and increases in industrial operations. This parallelogram as viewed from above is a tapestry on which the changes in urban form, industrial expansion and technological growth have been woven, unraveled, and rewoven, to create a story of maps that capture the changes that occurred in many American cities in the last century.

Map 9: Site very similar in appearance to today, NECCO still exists, railroad spurs still exist, Circa 1975

Map 9: Site very similar in appearance to today, NECCO still exists, railroad spurs still exist, Circa 1975  Map 10: Site in modern day, note Novartis building and Plasma Science and Fuaion Center, Circa 2015

Map 10: Site in modern day, note Novartis building and Plasma Science and Fuaion Center, Circa 2015

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbinization of the United States. New York: Oxford UP, 1985. Print.

Map 1: From: Lewis M. Hastings map of Cambridge City (Circa 1700). Harvard Library (http://ids.lib.harvard.edu/ids/view/46931238?buttons=y)

Map 2: From: Broad map surveyed by James Hayward (Circa 1838) Normal B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library (http://maps.bpl.org/id/12742)

Map 3: From: Brad map surveyed by W. A. Mason reduced from Haywards’s 1938 map (Circa 1857) Normal B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library (http://maps.bpl.org/id12714)

Map 4: From: Hopkins Atlas (Circa 1886) Harvard Library (http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/6740211)

Map 5 &6: From: Bromley Atlas of Cambridge (Circa 1894) Harvard Library (http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/6153011)

Map 7: From: Bromley Atlas of Cambridge (Circa 1903) Harvard Library (http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/6153086)

Map 8: From: Bromley Atlas of Cambridge (Circa 1916) Harvard Library (http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/6592027)

Map 9: From: Bromley Atlas of Cambridge (Circa 1930) Ward Maps (http://www.wardmaps.com/viewasset.php?aid=11)

Map 10: From: Sanborn Atlas of Cambridge (Circa 1975) Rotch Library at MIT

Map 11: From: “Cambridge, Massachusetts.” Google Maps. 12 April 2015. Web. 12 April 2015.