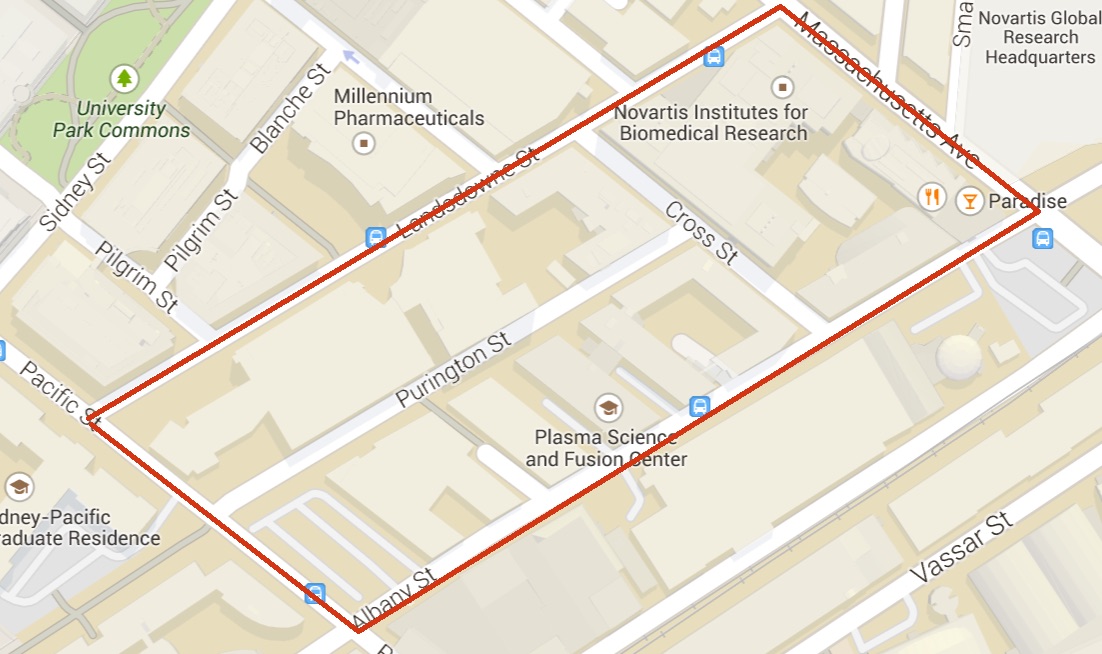

Outline of site on modern map (Image from Google Maps, April, 2015)

Outline of site on modern map (Image from Google Maps, April, 2015) My site has always been a unique site in the Cambridge area when being analyzed in any historical sense. Created through landfill, it is only roughly 120 years old, but it exists in one of the oldest cities in America. The history of its neighborhood in conjunction with its inception at a pivotal transition point in America’s industrial history and its proximity to a research institute with as high a caliber as MIT has allowed my site to serve as a blank slate for the effects of technological evolution, scientific pursuit, and societal values to be written on. These shifts in industry, technology, and human values have left visible traces on my site that have accumulated into two significant layers of particular periods in its history. These layers both point to larger trends that have been occurring in my site, in the larger Cambridge-Boston area, and in many more cities across the country.

My site has had several distinct periods of change. I wrote about these phases of change in my previous paper in which I spoke about the 1903 park construction, the 1916 rail spur and street construction, and the 1930 massive influx of buildings. Two of these periods of change have left clear layers on my site that are still visible today. Around 1916, when George Purrington purchased all the land in my site and broke it up into blocks, he was creating a framework for my site that has existed to this day. Purrington St., which cut through the center of my site was built to accommodate a rail spur that would later feed into the large NECCO factory that was built on Massachusetts Ave. This framework that Purrington established was the first layer on my site that is still visible today. Each street is an artifact from the 1916 site planning and Purrington St. itself is an artifact of a time when the railroad was much more heavily relied on for industrial purposes than it is today. This layer can be thought of as a transportation layer, a layer that was created as the network of arteries of my site. Not only are the streets themselves an artifact in this layer; there is a very interesting artifact that I found that is the perfect example of a trace of the rail spurs that once threaded through my site during the birth of mass production.

I knew that there were once rail spurs on Purrington St. by examining the old maps of my site, specifically the 1916 and 1930 Bromley maps. With this knowledge I scoured Purrington St. to see if I could find traces of these tracks that were once so prominent. In the middle of my site I found nothing, however on both ends I discovered something very interesting. The tracks once fed directly into the NECCO factory, and when I passed the location at which they used to enter the building, I noticed a very oversized rollup door (Fig 1). This door opening was obviously never modified since 1930 and has remained the same size due to its past need to accommodate freight cars. When I looked closer in this area, I noticed something that was fascinating, comical, and a bit eerie at the same time. Embedded in the concrete slab that protruded from under the large door there were two steel tracks that jutted out a few feet and then stopped abruptly when they hit the asphalt of the road (Fig 2). They were flush with the concrete so at some point between 1996 and 2015 they must have been filled in (this date can be ascertained by looking at the 1996 Sanborn map). These steel tracks are the epitome of a trace of the past. Where highly trafficked industrial freight cars used to rumble in and out of this factory now lie two pieces of cut rail, almost entirely hidden, save for their top surface. It is interesting to wonder why the new building owners or the contractor did not remove the tracks entirely. Why leave these few feet remaining? Perhaps the new owners and those involved in the removal of the tracks felt like there was some sort of sentimental attachment to this trace of an older era, and thought it valuable to hold onto it. This notion of preserving or reinserting the past is a sentiment innate to humanity and is touched on in Dolores Hayden’s Power of Place when she writes that planners must “think about where resonant parts of the past exist that should be protected, or where reminders of lost pasts may be reinserted into the changing urban landscape”(Hayden 234).

Fig. 3: Pedestrian walkway and green space in location of old rail spur (photo by author).

Fig. 3: Pedestrian walkway and green space in location of old rail spur (photo by author). On the opposite side of my site, still on Purrington St., I made another interesting discovery. I noticed when I looked across Pacific St. that there was a space between the buildings that continued on for some time. This space was in the same location as the rail spurs used to be (Fig. 3). Instead of constructing buildings or a road there when the tracks were removed, the planners of the site put in a pedestrian walkway with green space on either side. Knowing that railroad tracks used to cut through the buildings at this location explains why no long-standing structures exist in this space. Hayden draws attention in Power of Place to an idea of John Stilgoe’s, that the railroad is a “metropolitan corridor” that threads through the city. Throughout its history, construction to deconstruction, the railroad has shaped the space, buildings, and people around it. It seemed peculiar to me to realize that a pedestrian walk with surrounding green space was built there instead of a more utilitarian road, but this trace of the railroad tracks falls into a common theme of several other artifacts on my site; that is, the creation of green space.

This creation of green space over the evolution of my site becomes visible under analysis of a second overall layer on my site. This second layer is not a dynamic layer of the flow of people and goods like the transportation layer was, rather it is a layer of stationary buildings. These buildings were built around 1930 and although they still exist today, their uses have changed over time reflecting changes in manufacturing and technological evolution. As Hayden writes, “space is shaped for… economic production,” and this layer of my site clearly follows this notion as it has, through its history, responded so promptly to changes in technology by changing the industries to which it is home (Hayden 20).

There are three buildings in particular which I feel encapsulate this layer of my site: the large building which used to be home to NECCO and is now the Novartis headquarters, the Landsdowne building, which is now home to ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, and the building that used to be the Elliot Addressing Machine Co. and is now a MIT graduate dorm. The first two of these buildings are built of stone, and the last is of brick, which partly explains why they survived many of their contemporaries, which were built of wood. When viewing the Novartis building from the street, it does indeed have the appearance of a building from the early 1900’s with its stone facades and its large, split-pane factory windows (Fig 4). Despite the modern plastic Novartis sign that has been attached to the stone, the building is a true artifact of the dawn of mass production.

Fig. 4: Novartis building (old NECCO building), front facade. (photo by author)

Fig. 4: Novartis building (old NECCO building), front facade. (photo by author)  Fig. 5: Old fire call box and fire alarm system from front of Edgerton House (old Elliot Addressing Machine Co.)(photo by author)

Fig. 5: Old fire call box and fire alarm system from front of Edgerton House (old Elliot Addressing Machine Co.)(photo by author) Often, as Professor Spirn suggested in her lectures, people will try to make areas seem like they belonged to an older time period by installing old fashioned street furniture, lamps, and building hardware. The Edgerton House (the MIT grad dorm that now occupies the building that used to be the Elliot Addressing Machine Co.) displays some exterior features that give it this “ye oldies” appearance. Near its main door it has fixed to its wall a very old rusted fire call box and above it an old cast iron fire bell, which are artifacts from the 1930’s (Fig. 5). These features, coupled with oversized stone cornices above the doors give the brick building a very old look. Most likely, the fire system has been replaced since the time of the Elliot Co., however, the old bell and firebox were never replaced. This hearkens back to what Hayden writes when she says that often planners will leave certain features of the past intact to maintain the emotional and aesthetic connection many people have with them (Hayden 234).

The Landsdowne Building, which used to contain the Sears-Roebuck Shoe Factory also has features that point to its age. Not only is the building clearly in the architectural style of an older period, but it has modern adaptations that have been attached to it which have had to be built to accommodate the original structure. There is a large network of ductwork that is mounted on the exterior façade of the building. This ductwork would usually be within the walls and floors of a modern building, but since the building was built before it was customary to leave this utility space between floors, there was not sufficient space. This façade of ductwork is a modern layer on a 1930’s artifact.

Each one of these three buildings; the Novartis building, the Landsdowne building, and the Edgerton House, was built as a factory during a time when mass production had just become rampant in the United States. All three of these buildings had a common shape that was perhaps indicative of a customary factory layout plan during that time period. They were shaped roughly as a square “U” to create a central courtyard that was surrounded on three sides. In addition, each of the buildings had an annex building in its courtyard space that served to essentially seal off the courtyard on the fourth side. When each of these buildings was still being used in its original faculty, the courtyards most likely served as an open space for the flow of materials and machinery between buildings and between steps in production. NECCO’s courtyard, for example, held a power plant, a filling station, and a garage. These three buildings are obviously very utility-oriented and clearly serve functions that would be advantageous for a factory. These highly trafficked industrial courtyards humming with the hubbub of mass production would be only transient features, however, in the heart of my site.

Two distinct changes in relation to these courtyards occurred after the 1990s that are suggestive of larger trends that have been sweeping over my site. The first of these changes is in the nature of the companies that inhabited the buildings that surrounded each courtyard. In the 1990’s and early 2000’s, the growing establishment of MIT in Cambridge along with a global technological explosion in the field of biotechnology influenced the buildings in the greater area of Cambridge heavily, especially on my site. Both the Landsdowne building and the NECCO building changed owners and went from being factories to the research-oriented biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies of Novartis and ARIAD Pharmaceuticals. The Elliot Addressing Machine Co. changed ownership and became the MIT graduate dorm called the Edgerton House. This change in use symbolizes the effects MIT has had expanding into the existing Cambridge neighborhood, taking over buildings as it grows. The shift in use from factory to research institution echoes a change in the evolution of technology and science and my site has quickly adopted whatever industry is at the vanguard of research. I believe that this trend will continue, and as new technologies are developed and as new fields of research become more prominent, I believe that the buildings on my site will be adaptive again and will change use. This nature of my site can be closely linked with its proximity to MIT, one of the top research institutions in the world, and is a very concrete effect of the institute’s move to Cambridge.

A second trend can be discerned by looking at what happened to the courtyards previously introduced. As mentioned, the original role of these courtyards was to serve as open spaces where industrial shipping, receiving, and handling could take place. In the 1990’s, however, an interesting trend started occurring. Novartis took over the NECCO complex, and since the nature of the industry no longer required truck ports, power stations, a garage, or a filling station, these features were removed. In their place, the Novartis planners built a small park. They built benches, paved areas and raised planting beds, and planted trees and ground cover to make a central garden for their employees (Fig. 6). The Landsdowne building lost its previous occupant, the shoe factory, became home to ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, and underwent a similar process as the Novartis building. The courtyard was turned into a very nice garden with grassy areas, many flower beds, and several large trees (Fig. 7). Lastly, in similar fashion, the Elliot Addressing Machine Co. left its building, which became the Edgerton House, and the central courtyard was converted into a large lawn with surrounding paths, barbeque pits, and planted areas (Fig. 8). These three instances of industrial courtyards being turned into green spaces point to another trend that is occurring on my site.

The adaptation of these courtyards to the new uses of their surrounding buildings shows how “change in time can be traced in incremental modifications of space as much as in original city plan or building plan” (Hayden 15). The courtyards were no longer useful as industrial loading zones, but why weren’t they converted into parking lots or something more “practical”? The notion of a value and need for green space is a trend that my site displays and is a trend that cities across America have increasingly displayed in recent decades. Not only are efficiency, compactness, and productivity on the top of the list of priorities for urban environments, now quality of life and the ability to interact with nature are becoming just as important. The conversion of these courtyards into green space very closely emulates the construction of the Highline Park in New York City. In that case, an abandoned elevated railroad was converted into a long, beautifully planted park. This conversion of an old and unused industrial space into green space is very similar to what has occurred on my site. In fact, I can imagine this continuing to happen on my site with many of the small abandoned pieces of property and buildings that have fallen into disrepair at the corner of Albany St. and Pacific Street. This trend of tucking green space into any nook or cranny that opens up in a dense metropolitan area is a trend that I observed on the small scale on my site, and through direct experience, I know is occurring in urban cities across the United States.

In any analysis of the city, I believe that there is one fundamental idea that must be addressed. This idea is that the city is a man made, rigid, impermeable construct existing in an environment that is fluid, flexible, unpredictable, and operating under natural processes. As Professor Spirn writes in The Language of Landscape, “Planners' maps show no buried rivers, no flowing, just streets, lines of ownership, and proposals for future use, as if past were not present, as if the city were merely a human construct not a living, changing landscape” (Spirn 11). This reiterates the necessity to view the city not as a rigid entity existing independently of nature, but rather as a living, breathing entity, part of nature itself. Through the natural processes paper it became evident that if a city is build in disregard for natural processes, these same processes will destroy what has been built with merciless symbolic retribution and the city planner will be driven back to square one. In the second and third papers it is now apparent that after the entire history of my site and how it has responded to changes in industry, the overriding trend that has surfaced is the necessity to allow for green space; to accommodate nature. My site displays a predominant layer of the changes in building use that signify changes in technological pursuits. It also possesses a layer of change over time in the use of space in its commercial courtyards that strongly emphasizes the importance of consciously building and adapting cities to include green space. If there is one lesson I have taken away from closely analyzing this site, it is that in order for a city, or really any building, to be successfully built in the long term, it must be built in concord with nature not in denial of it.

Spirn, Anne W. The Language of Landscape. New Haven: Yale UP, 1998. Print.

Hayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History.Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1995. Print.