The natural processes at work at Magazine Beach and its adjacent section of Memorial Drive have influenced the way humans have developed the area, and have themselves been altered by human activity. The riverside location likely drew people to settle the Cambridgeport. Ever since, people have been transforming the natural state of the site: introducing impervious surfaces to what was once a wetland, building bridges, polluting the river, changing wildlife migration patterns, and impacting the climate through global warming. And today, those changes show through in the ways in which natural processes effect human processes: through cracks in our infrastructure, adaptations to a river too contaminated for use, cohabitation with other resident species, and attempts to manage this winter’s record snowfall. Humans alter natural processes, and the changes affect how humans function in the environment.

Human settlement has completely altered the state of the land that is now Magazine Beach and Memorial Drive. According to a 1865 map of Cambridgeport (Figure 1), the entire area was once a marsh. This environmental history is still evident along the trail that runs through Magazine Beach. The ground is soggy, often forming mud puddles in the dirt section of the path that follows the river. Cattails and long grasses are the main vegetation near the riverside, besides the artificially planted trees and grass field, further indicating the swampy history of the area.

Figure 1: Cambridgeport circa 1865. Textured areas indicate marsh land. The red line extending to the River’s edge shows the location of today’s Boston University bridge. Source: "Historical Viewer." Cambridge CityViewer. City of Cambridge, MA, 1 Jan. 2015. Web. 6 Mar. 2015.

Figure 1: Cambridgeport circa 1865. Textured areas indicate marsh land. The red line extending to the River’s edge shows the location of today’s Boston University bridge. Source: "Historical Viewer." Cambridge CityViewer. City of Cambridge, MA, 1 Jan. 2015. Web. 6 Mar. 2015.

In the winter, wells form in the snow around the trees planted throughout the park, perhaps due to the porous ground beneath. Marsh grasses can be seen sticking up through the thick snow cover. Further from the river, the pavement of Memorial Drive may present more evidence of the land’s old state. Intense cracking indicates overuse and seasonal freezing, but it may also suggest that the ground beneath the thoroughfare is soft and porous. Where cars and school busses stop at the intersection of Memorial Drive and the Boston University bridge, extreme shoving that can be observed, as in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Warped pavement on Memorial Drive may be partially due to the area’s history as a wetland.

Figure 2: Warped pavement on Memorial Drive may be partially due to the area’s history as a wetland.

According to James Elkins in How to Use Your Eyes (Elkins, 2000), shoving is the displacement of a top layer of pavement by vehicles, especially heavy ones, and especially as they stop and start. It requires a detachment of the asphalt layer from the underlying material, so since Memorial Drive was laid on top of a drained marsh, it makes sense that it would display such a severe case. Cracks are also evident around the the storm drains on Memorial Drive (Figure 3). When asphalt replaces more pervious surfaces during urbanization, drainage and water contamination become serious concerns. Rain that falls on roads, along with the silt and oil it picks up, is washed into storm drains that empty into waterways, usually untreated. In the case of Memorial Drive, the drains most likely lead to the Charles. In this way, pollutants from the busy street enter the river. The cracks around the storm drain seen in Figure 3 suggest that along the way the water puddles and stagnates, due to inadequate drainage. The cracks may simply indicate overuse, but their proximity to the drain imply that they are the result of a drainage issue, which is in turn a consequence of the ground’s change from porous and marshy to impervious. With the introduction of pavement and asphalt, humans have transformed what was once a wetland into the park and thoroughfare it is today, but the original state of the land still shows through in the cracks and potholes in the infrastructure that altered it.

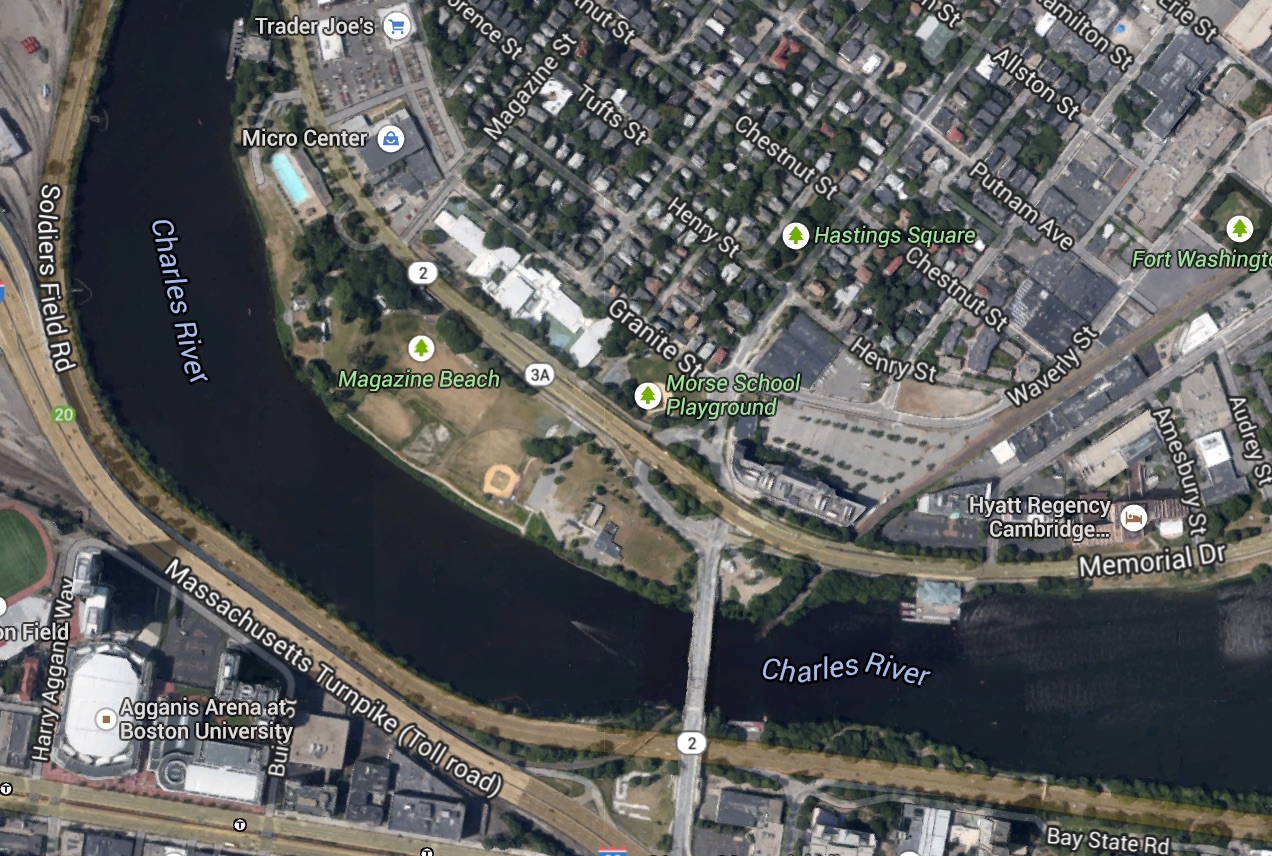

Figure 3: Cracks surrounding a storm drain on Memorial Drive may be indications of pour drainage due to underlying former marsh. Source: “Cambridge, Massachusetts.” Map. Google Maps. Google, 2015. Web. 06 Mar 2015.

Figure 3: Cracks surrounding a storm drain on Memorial Drive may be indications of pour drainage due to underlying former marsh. Source: “Cambridge, Massachusetts.” Map. Google Maps. Google, 2015. Web. 06 Mar 2015.

When infrastructure doesn’t change the natural features of the land, it must be designed to accommodate the existing environment. Though the shape and water quality of the Charles River has changed over time, a large part of human interaction with the river has been adaptation to its presence as a break. The Boston University bridge spans the river at one of its narrowest points between Harvard and the dam at the Museum of Science. From the 1865 map of Cambridgeport (Figure 1), the location appears to be a natural narrowing of the river before it opens on its way to the harbor. In fact, the site of what is now the Boston University bridge seems to have been in 1865 the last traversable span of the river before it became a wide estuary. This is shown in the maps in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Historical and recent maps of Magazine Beach and surroundings. Note in the 1856 map the widening of the Charles immediately East of the current site of the Boston University bridge. Source 1: "Historical Viewer." Cambridge CityViewer. City of Cambridge, MA, 1 Jan. 2015. Web. 6 Mar. 2015.

Figure 4: Historical and recent maps of Magazine Beach and surroundings. Note in the 1856 map the widening of the Charles immediately East of the current site of the Boston University bridge. Source 1: "Historical Viewer." Cambridge CityViewer. City of Cambridge, MA, 1 Jan. 2015. Web. 6 Mar. 2015.

Humans took advantage of this natural feature and built what would become the Boston University bridge. However, the convenience of the narrow crossing was accompanied by the problems of building on a swamp, as discussed previously— not to mention the environmental impact of destroying what was perhaps a vibrant wetland. Now, the most apparent impact of the location of the bridge is the thick traffic that crosses it and joins Memorial Drive. The location of Boston University bridge is a derivative of the natural shape of the land and river, and now it acts as a prominent feature of the stretch of Memorial Drive bordering Magazine Beach.

A large part of human interaction with the Charles river has been its contamination. Like London’s River Thames as described in The Granite Garden (Spirn, 1984), the Charles River was once a stinking urban waste dump (“Charles River History, 2015). In 1855, the Thames was “an open sewer” (Doxat, 1977, via Spirn, p. 134). Similarly, from the beginning of the 20th century through the mid-sixties, the Charles became extremely polluted by industrial waste, sewage, and residential rubbish. Cambridge, it seems, failed to learn from London’s example a century previously (London also seems to have missed the lesson: the Thames remained extremely polluted until the 1950s [Wheeler, 1979, via Spirn, p. 135]). In 1949, Magazine Beach was closed due to health concerns surrounding the river (“History”, 2011). Magazine Beach was once a salt water swim area; that part of the river became fresh when the estuary was dammed in 1910 (“History”, 2011). Swimming became progressively less popular before it was banned in 1949, and swimming in the Charles remains unpopular, though the river was declared swimmable over a year ago (Baker, 2013). Now Veteran’s Memorial pool (Figure 5) provides the opportunity for swimming that the river itself once did.

Figure 5: The construction of Veteran’s Pool at again Beach was likely a reaction to the contamination of the Charles. Source: “Cambridge, Massachusetts.” Map. Google Maps. Google, 2015. Web. 06 Mar 2015.

Figure 5: The construction of Veteran’s Pool at again Beach was likely a reaction to the contamination of the Charles. Source: “Cambridge, Massachusetts.” Map. Google Maps. Google, 2015. Web. 06 Mar 2015.

The pool was built after 1949, once the river was too polluted for recreational use. The pool’s existence illustrates how humans adapt to the changes we ourselves impose on our environment. The infrastructure and patterns of life surrounding the river today are traces of the community’s historical interactions with its natural context.

The way in which humans interact with wildlife changes the natural environment, and the resulting behavior of wildlife in turn impacts human processes. A clearing on the riverside near the Boston University bridge exemplifies this relationship. Year-round, the clearing is crowded with geese (Figure 6).

Figure 6: A flock of geese has established permanent residence in this field on the riverside near the Boston University bridge.

Figure 6: A flock of geese has established permanent residence in this field on the riverside near the Boston University bridge.

Geese are migratory birds, but it appears they’ve taken up permanent residence in this particular area by the Charles. This may be because there is an abundance of food for such birds in an urban environment. It could also be because the birds are decedents of captives who were set loose and never learned to migrate (“Why Do Canada Geese Like Urban Ares?”, 2012). Human decimation and subsequent artificial renewal of wild populations has forever changed the behavior of these animals. And now the change impacts human use of the space. Goose feces abound at Magazine Beach and beside the trails that run parallel to the river. Bird behavior disrupts car and pedestrian traffic. It’s not uncommon to see cars stopped at the intersection of Memorial Drive and the Boston University bridge, waiting for a line of geese to cross at the crosswalk. The flock, which is now a fixture of the environment, is there due to human meddling in the natural process of wildlife migration. The result of this altered natural process directly impacts human processes in the areas adjacent.

Humans influence global natural processes, and the effects can be seen on individual sites. Through the burning of fossil fuels, humans have warmed the global climate, since greenhouse gasses such as carbon dioxide and methane trap heat in the atmosphere. A counterintuitive effect of this warming is an increase in winter storm strength and precipitation in Boston (Mooney, 2015). According to Michael Mann, a Penn State climate researcher (quoted by Chris Mooney in a February 10 article in the Washington Post), warmer sea surface temperatures increase the amount of moisture in the air on the East Coast of the United States, bringing more snowfall when that moisture condenses (Mooney, 2015). Mann provides evidence in Mooney’s Washington Post article that ocean surface temperatures off the coast of Massachusetts have risen in some places by 11.5 degrees centigrade (21 degrees Fahrenheit) (Mooney, 2015). This drastic alteration shows its effects on Memorial Drive in the form of mountainous snow banks on either side of the road. This winter, Magazine Beach is currently all but inaccessible, completely buried under three to four feet of snow. The pedestrian walkway that usually carries foot traffic from the Morse Elementary School on the northeast side of Memorial Drive across to the park is packed with snow and ice, and any semblance of a path disappears as soon as the walkway ends at Magazine Beach. In the residential neighborhood behind the school, homeowners carve out parking spaces from the vast banks. Snow is piled in the bike lane on Brookline, normally a bike route from Boston University bridge to Inman Square. Sidewalks have been reduced to foot-wide passageways between snow banks. Cambridge knows how to deal with snow, but the record snowfall of 2015 still impedes human activity in the city. Reactions to extreme winter weather illustrate how human transformation of natural processes comes full circle to shape human behavior.

Humans alter natural processes in local and global ways. We reshape our environment as we use it. We change the properties of the land, the accessibility of areas separated by natural features, the quality and utility of waterways, the behavior of wildlife, and the climate. The consequences of those changes crop up in unexpected ways, and in turn influence how humans use the space. Changes we inflict on natural processes change the way natural processes affect us. The traces of Magazine Beach’s marshy past and its urban transformation change our experiences of the park and Memorial Drive adjacent to it. Boston University bridge and Veteran’s Memorial Pool stand as reminders of Cambridge’s complex relationship with the Charles. Wildlife behavior and extreme winter weather illustrate the permanent effect humans have on the natural environment we inhabit. In Cambridgeport and around the world, the human relationship with natural processes is composed of circular interactions: the successive adaptations of the human population to its environment and the environment to the influences of its human inhabitants.

Works Cited

Baker, Billy. "Charles River Opens for Public Swim for First Time since 1950s - Boston.com." Boston.com. The Boston Globe, 13 July 2013. Web. 28 Feb. 2015.

"Charles River History | Charles River Watershed Association." Charles River History | Charles River Watershed Association. Web. 28 Feb. 2015.

Doxat, John. The Living Thames: The Restoration of a Great Tidal River (London: Hutchinson Benham, 1977), p. 32.

Elkins, Jame. How to Use Your Eyes. Routledge: New York, NY. 2000: pp. 28-33

"History." Magazine Beach. 9 Nov. 2011. Web. 28 Feb. 2015.

Mooney, Chris. "What the Massive Snowfall in Boston Tells Us about Global Warming." The Washington Post 10 Feb. 2015. Web. 6 Mar. 2015.

Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic, 1984. Print.

Wheeler, Alwyne. “Fish in an Urban Environment,” in Nature in Cities, ed. Ian C. Laurie (Chichester, England: Wiley, 1979), p. 163.

"Why Do Canada Geese Like Urban Areas?" Humane Society. The Humane Society of the United States, 26 Mar. 2012. Web. 6 Mar. 2015.

All photos by author unless otherwise noted.