The Brookline neighborhood was designed in large part for the use of automobiles. The area’s environmental history and resident demographic, along with the political and cultural tone of the times in which it was developed, contributed to this trend. Late development, a middle- to upper-class population, and a national political bias helped infrastructure for the automobile dominate. Due to its marshy origins, the neighborhood developed in the age of the automobile, without an era of public transportation preceding. Wealthy residents most likely bought cars early in their production. Memorial Drive and Brookline developed in parallel with the rise of the automobile nationally, so automobile infrastructure featured heavily in that development. The area seems to have been poised to accept the car, and the prevalence of automobiles in turn shaped the site through time.

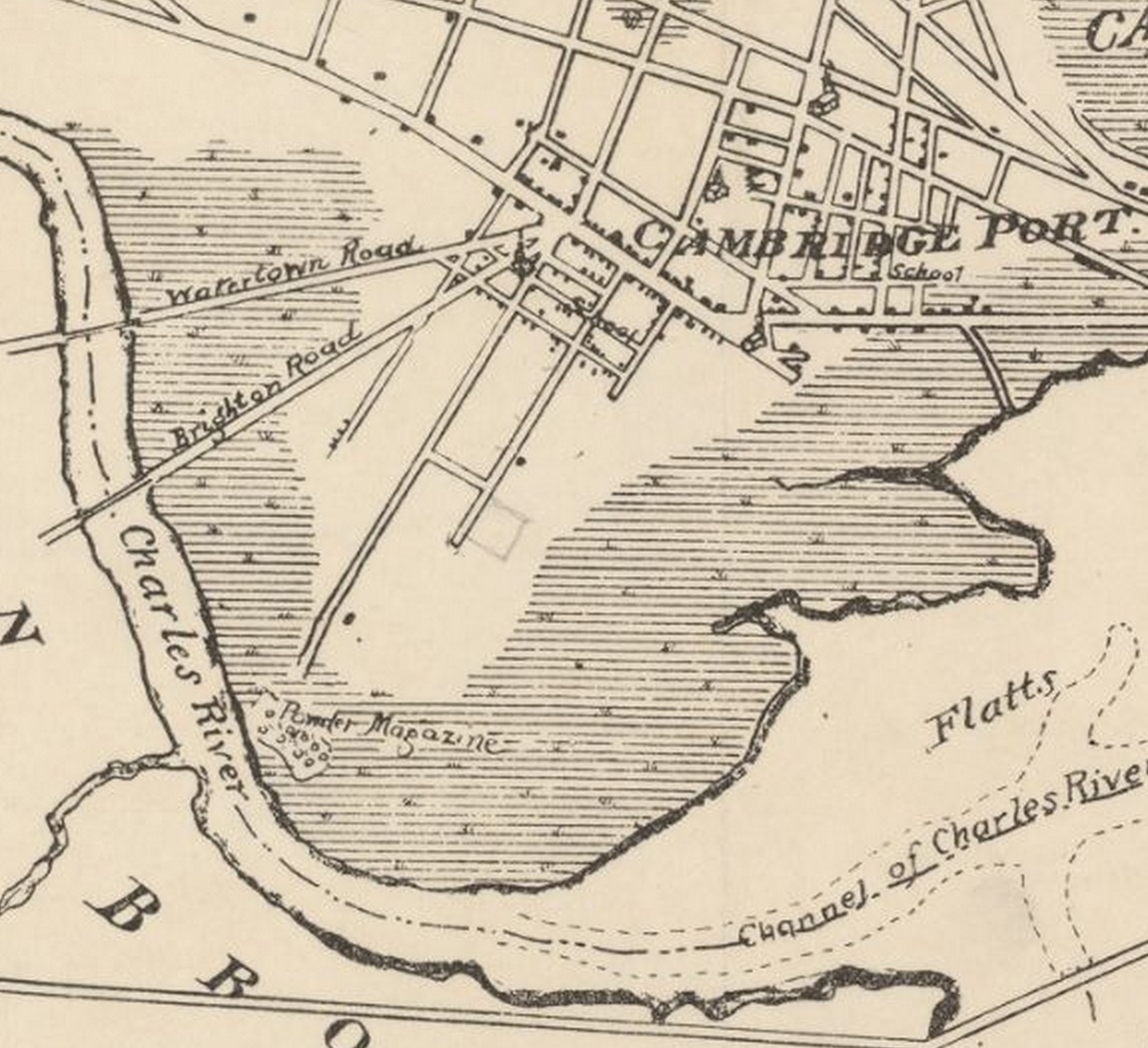

The environmental history of the site that is now Magazine Beach and the Brookline neighborhood contributed to its later domination by the car by delaying its development. As shown in Figure 1, the area was undeveloped marsh land until the mid-nineteenth century. While other parts of the city sported a robust streetcar system, riverside Cambridge had no need for public transportation, because it did not yet have a residential population to serve. In fact, no streetcar lines are apparent on the site at any time in its history: the area was not developed until the advent of the automobile and the beginning of the streetcar’s demise. By the time there was a population big enough to merit public transportation infrastructure, public transportation was falling out of favor, to be replaced by private mode of mobility.

Figure 1: Cambridgeport circa 1830 Hatched areas indicate marsh land. In the mid-1800s, the state powder magazine appears to occupy the only dry land on the site that is now Magazine Beach and the Brookline neighborhood. Source: Hales, J. G. Plan of Cambridge: From Survey Taken in 1830. Digital image. Image Delivery Service: Harvard University Library. Web.

Figure 1: Cambridgeport circa 1830 Hatched areas indicate marsh land. In the mid-1800s, the state powder magazine appears to occupy the only dry land on the site that is now Magazine Beach and the Brookline neighborhood. Source: Hales, J. G. Plan of Cambridge: From Survey Taken in 1830. Digital image. Image Delivery Service: Harvard University Library. Web.

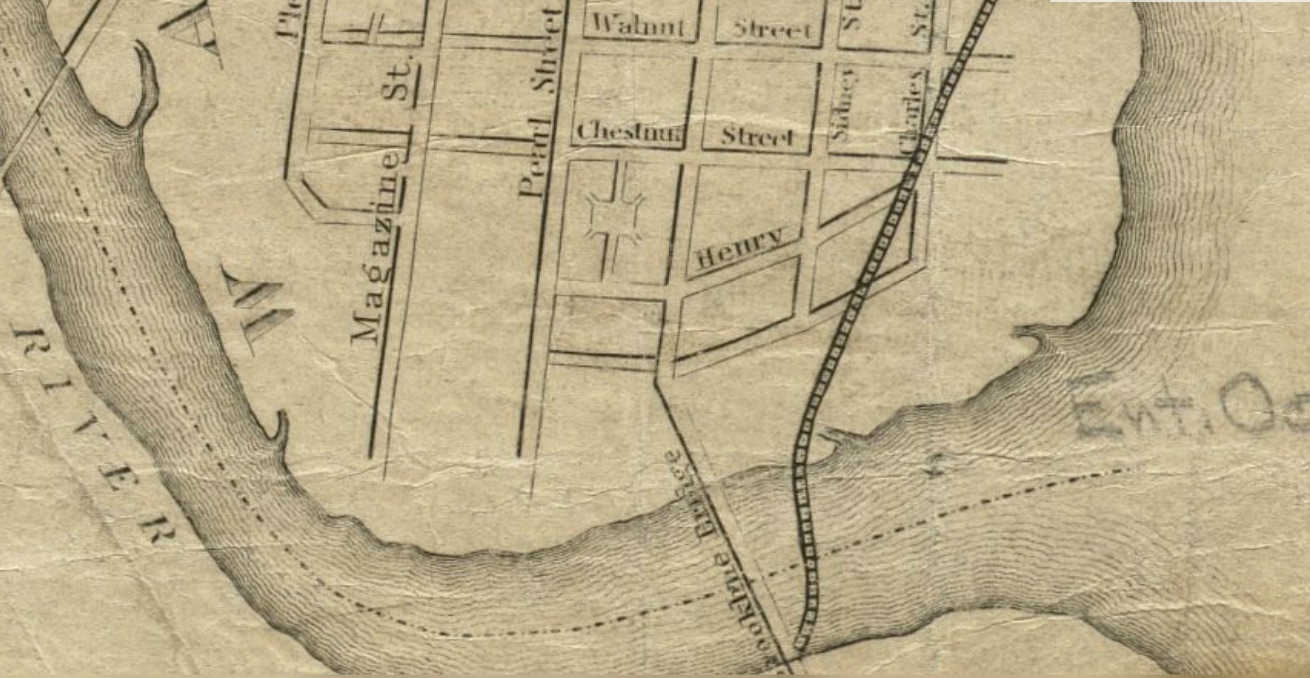

The Boston and Albany Railroad arrived in Cambridge between 1830 and 1857. In Figure 2, the tracks can be seen running northeast to southwest and crossing the Charles River near the Brookline Bridge (now the Boston University Bridge). Rail was the dominant mode of long-distance travel in America until the advent of the automobile, so in the nineteenth century the railroad was most likely the link between Boston harbor and trade centers further inland, as well as the only form of long-distance mobility for urban populations. However, there does not appear to have been a stop near the current site of Magazine Beach, most likely because the area had not been developed. With no homes or factories to service, the railroad merely passed through. Like the streetcar system, the otherwise robust railroad was not built to directly serve the area. Though steam rail transport experienced a “golden age” in the 1920s and Boston in particular had a strong commuter rail system later into the twentieth century (Jackson, p. 171), the late development of the Brookline area coincided with a wave of such cultural, political, and economic enthusiasm for the automobile that even rail could not assert dominance before private transport exploded into the forefront.

Figure 2: Brookline circa 1857 The first appearance of the Boston and Albany Railroad occurs in 1857, with a single track running diagonally from the northeast and crossing the Charles River near the Brookline Bridge. The railroad would later expand, but would never come to dominate the area the way the automobile did. Source: Mason, W. A., and John Ford. Map of the City of Cambridge, Mass., Reduced from J. Hayward's 1838. Digital image. Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library. Web.

Figure 2: Brookline circa 1857 The first appearance of the Boston and Albany Railroad occurs in 1857, with a single track running diagonally from the northeast and crossing the Charles River near the Brookline Bridge. The railroad would later expand, but would never come to dominate the area the way the automobile did. Source: Mason, W. A., and John Ford. Map of the City of Cambridge, Mass., Reduced from J. Hayward's 1838. Digital image. Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library. Web.

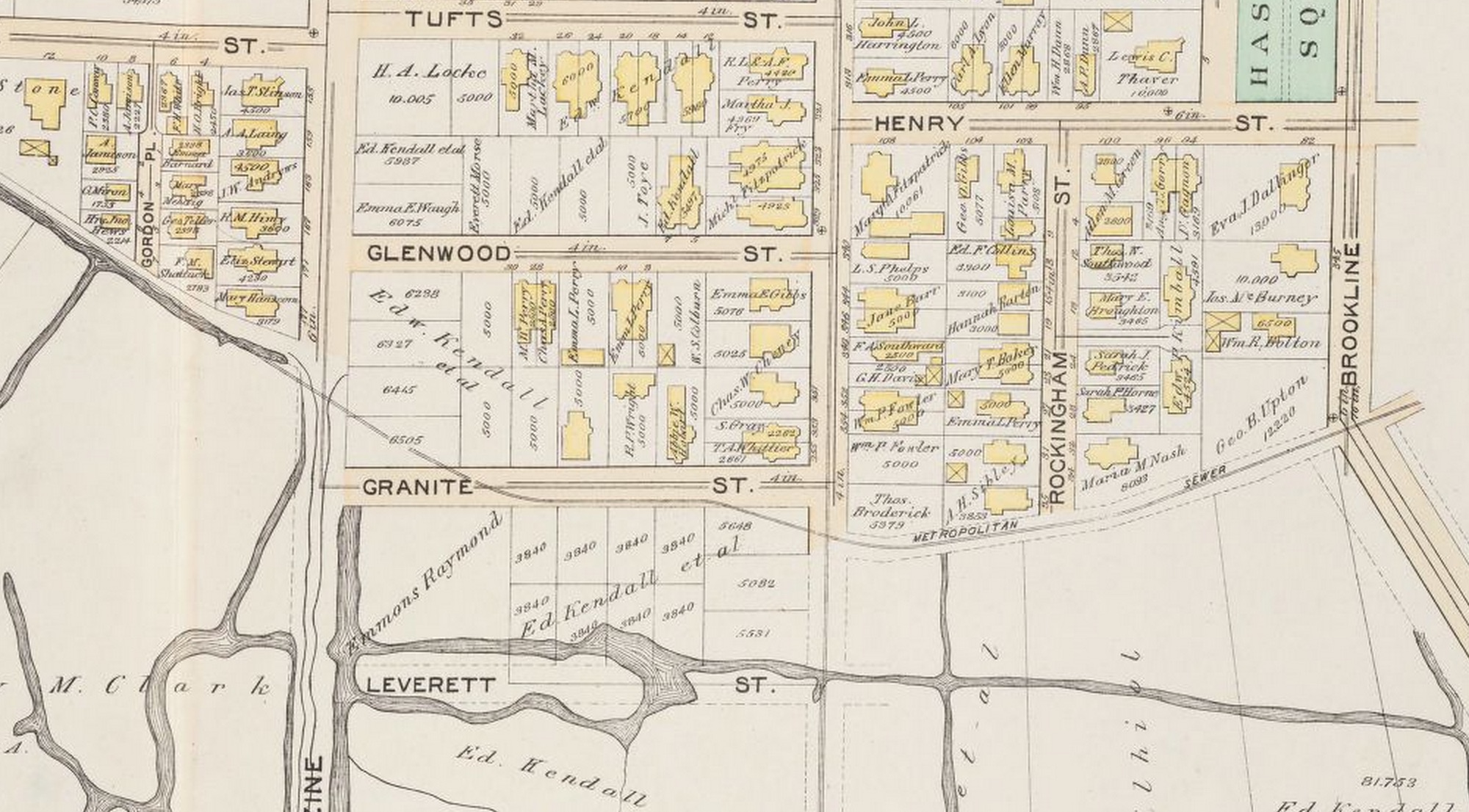

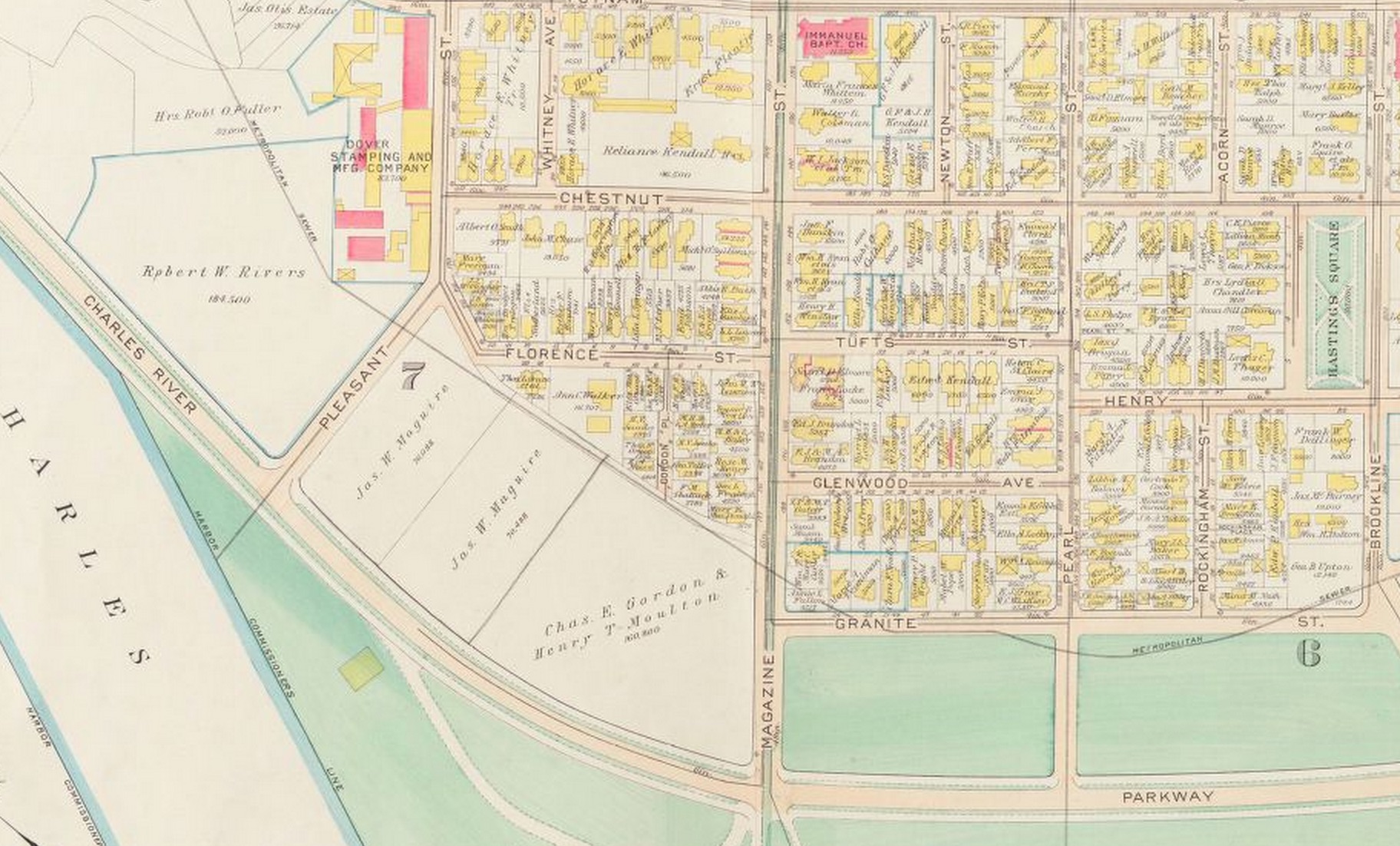

The Brookline area finally began development in the late nineteenth century. In 1877, very few buildings appear in what is now the Brookline neighborhood; in 1894, a boom of construction seems to have taken place. The original development matches the land use of the area today: larger, privately-owned lots with single-family homes. The names over individual lots in Figure 3 suggest that buildings were owner-occupied, not rental property. These trends suggest that the area was predominantly home to a wealthier socio-economic class: people who could afford to own their own homes. Several owners are designated as “heirs”, and the names that follow are recognizable as the namesakes of important Cambridge sites today. Tufts and Kendall, for example, were presumably wealthy families, as they now have a university and a square in their names, respectively. Interestingly, a large portion of property owners appear to have been women: names like Mary, Maria, Sarah, and Eva are listed as owners of many lots. The surnames of landowners show that the population was mainly Irish and English immigrants: Fitzpatrick, Dallinger, Locke, and the like. This boom in development occurred well after the immigration wave fueled by the Irish potato famine in the 1840s, so the landowners were most likely not poor Irish farmers fleeing starvation. Additionally, famine immigrants were largely Catholic (“Irish Potato Famine”), while earlier periods of immigration brought Irish Protestants, and no Catholic church appears on the 1894 map of the site. There is only the Charles River Baptist Church to the north (not pictured). Additionally, poor, working-class famine immigrants would most likely not have been able to afford such large plots, even on former marsh land. These observations support the hypothesis that the owners (and presumably residents) of the early Brookline neighborhood were established American families with ancestry in the United Kingdom, but were most likely not first-generation immigrants. The socio-economic position of the area’s demographic set it up to develop as a society centered around the car.

Figure 3: Beginnings of development in 1894 Single- and double-family buildings sprang up in Cambridgeport in the late 1800s. Owners of the large plots have Irish and English surnames such as Dallinger and Locke. Many plots have female owners: for example, Eva J. Dallinger appears to own the rectangular property at the corner of Brookline and Henry streets (purple). Source: Bromley, G. W. G.W. Bromley & Co. Atlas of the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts :from Actual Surveys and Official Plans. Digital image. Harvard University Library Image Delivery Service. 1 Jan. 1894. Web.

Figure 3: Beginnings of development in 1894 Single- and double-family buildings sprang up in Cambridgeport in the late 1800s. Owners of the large plots have Irish and English surnames such as Dallinger and Locke. Many plots have female owners: for example, Eva J. Dallinger appears to own the rectangular property at the corner of Brookline and Henry streets (purple). Source: Bromley, G. W. G.W. Bromley & Co. Atlas of the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts :from Actual Surveys and Official Plans. Digital image. Harvard University Library Image Delivery Service. 1 Jan. 1894. Web.

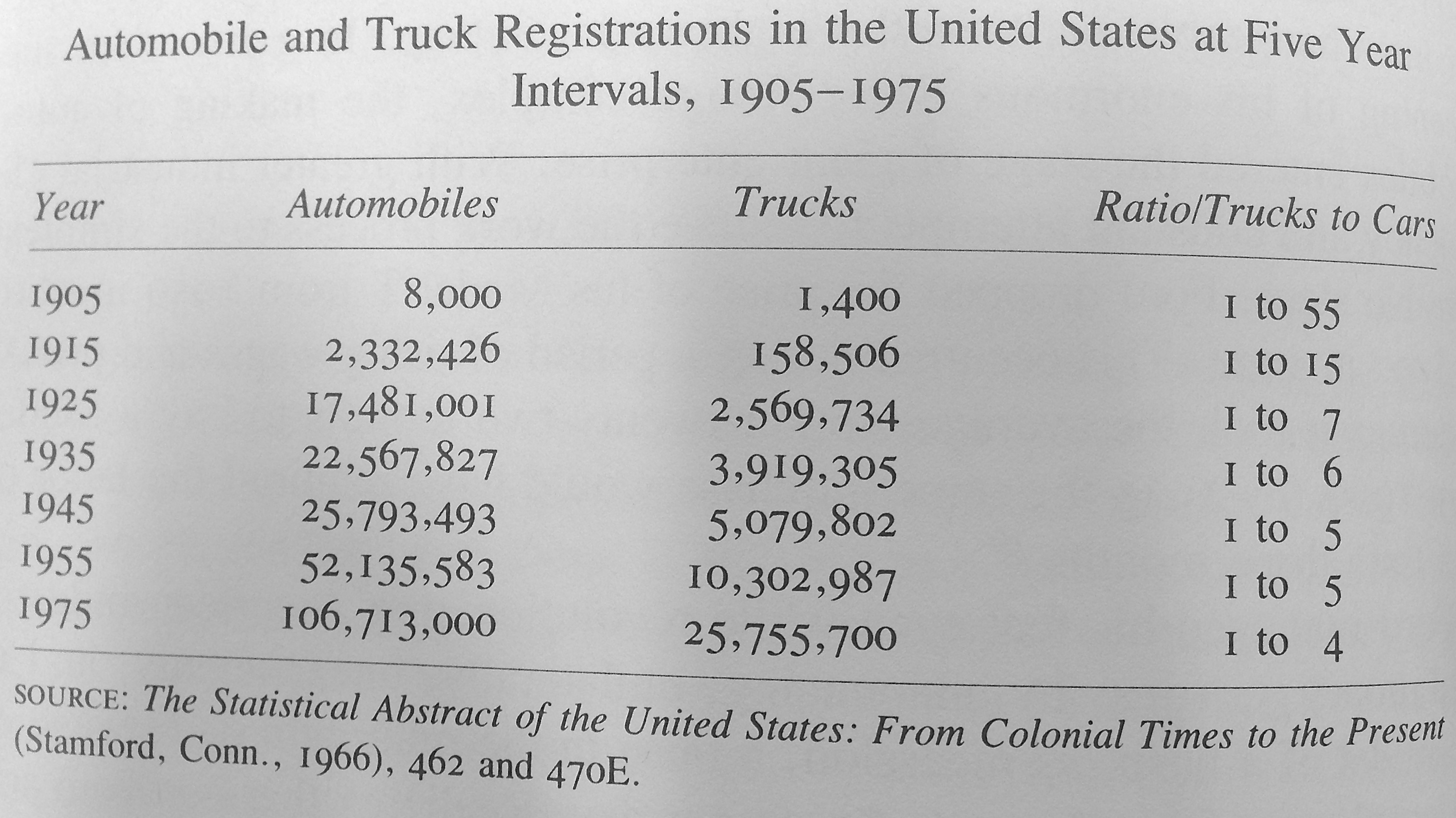

The rise of the automobile and the accompanying cultural, economic, and political shift proved transformative to American cities, presumably including Cambridge. In the twentieth century, American car ownership rose exorbitantly (see Table 1). The beginning was not the invention of the automobile, but rather the introduction of the Ford Model T: an affordable, serviceable product designed for the middle class citizen (Jackson, p. 160). As discussed previously, the Brookline neighborhood was most likely predominantly middle class, so car ownership may have risen there in the early 1920s, when the Model T was first mass produced. From that early time, automobiles were seen as a huge positive addition to the urban lifestyle. They were more convenient, less space-intensive, and considered cleaner than the previously prevalent horse-drawn trolleys (Jackson, p. 163). Also contributing to the transformative force of the automobile was the backing of diverse interest groups, including oil and rubber companies, tire producers, and merchants eager for a more mobile customer base (Jackson, p. 163). As a result of lobbying and positive public opinion, politics began to shift development radically in favor of the automobile. Instead of taxing car purchases to pay for new roads, governments diverted general taxes for their construction (Jackson, p. 163). This trend of political alignment with proponents of the automobile would continue throughout the twentieth century (and arguably persists to the present), and was likely a large factor in the way the Brookline neighborhood developed.

Table 1: “Automobile and Truck Registrations in the United States at Five Year Intervals, 1905-1975” Vehicle ownership increased rapidly, especially in the mid-twentieth century (though not as much in the Depression years). Ownership of trucks increased even more quickly, increasing pressure for, or perhaps in answer to, the construction of new highway systems. Source: Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford UP, 1985. Print.

Table 1: “Automobile and Truck Registrations in the United States at Five Year Intervals, 1905-1975” Vehicle ownership increased rapidly, especially in the mid-twentieth century (though not as much in the Depression years). Ownership of trucks increased even more quickly, increasing pressure for, or perhaps in answer to, the construction of new highway systems. Source: Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford UP, 1985. Print.

A major addition to the Brookline area between the turn of the century and 1916 was the construction of Charles River Parkway, a wide new road winding along the river, which intersected Brookline Street at the Brookline Bridge. The road runs across the bottom of Figure 4. According to Kenneth Jackson in his urban history The Crabgrass Frontier, parkways were an answer to a new demand for congestion-free venturi with the rise of the automobile: “Because traffic clogged even large thoroughfares…most urban regions soon proposed “express” streets without any stoplights or intersections at grade. The first of the new type were called parkways because the land on either side of the travel ways was typically part of a park and because parkways followed natural topography of the land…” (Jackson, p. 165). By this description, Charles River Parkway seems to have been a quintessential example of this new kind of roadway. It was separate from block-by-block cross traffic, it appears to have been surrounded by green space, and it was most likely scenic, as it followed the river. It was probably used for both utilitarian and pleasure driving. By 1913, there was one car for every eight people in America (Jackson, p. 159), and the automobile was quickly percolating into all aspects of middle class life, including recreation. This technological and cultural shift was beginning even in 1916 to revolutionize American cities, including Cambridge.

Figure 4: New roadways in 1916 Charles River Parkway (purple) was built in the early twentieth century. The construction of this thoroughfare is reflective of a massive cultural and political shift in favor of the automobile, and to the receptiveness of this particular community to its rise. Source: Bromley, G. W. G.W. Bromley & Co. Atlas of the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts :from Actual Surveys and Official Plans. Digital image. Harvard University Library Image Delivery Service. 1 Jan. 1916. Web.

Figure 4: New roadways in 1916 Charles River Parkway (purple) was built in the early twentieth century. The construction of this thoroughfare is reflective of a massive cultural and political shift in favor of the automobile, and to the receptiveness of this particular community to its rise. Source: Bromley, G. W. G.W. Bromley & Co. Atlas of the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts :from Actual Surveys and Official Plans. Digital image. Harvard University Library Image Delivery Service. 1 Jan. 1916. Web.

The next major addition to national car infrastructure came in the form of graded expressways and interstate highways. By 1930, a new road was created along the Charles: Memorial Drive. In the 1970 map in Figure 5, it can be seen diverging around an oblong traffic circle and splitting into a concrete overpass. Graded streets, with overpasses and underpasses, were the next generation of parkways, designed for express transport by automobile and only automobile (Jackson, p. 166). Several factors in the twentieth century contributed to the paving of America, and by inclusion the creation of Memorial Drive. The Federal Road Act of 1921 promised matching funds from the Federal government to any state that set out to build a highway system (Jackson, p. 167). It also created the Bureau of Public Roads, which planned interstate highways to connect every city in the country with a population over 50,000 (Jackson, p. 167). During the Great Depression, road projects were favored because they were easy to plan and employed numerous workers (Jackson, p. 167).

Figure 5: Memorial Drive, Charles River Parkway, and the Brookline Bridge traffic Circle, 1970 Memorial Drive can be seen diverging around a traffic circle where it crosses Brookline, as it does today. The concrete overpass (underlined in purple) is an example of an attempt to free the thoroughfare from cross traffic. Source: Sanborn Atlas: Cambridge 1970. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Library.

A filling station, parking decks, an auto repair shop, and a used car lot along Memorial Drive in 1970 (Figure 6) reveal the prevalence of the automobile and the ubiquity of the industries that sprang up to complement it. In 1943 these industries, including car manufacturers, oil and rubber companies, and the American Trucking Association, formed a powerful lobby: the American Road Builders Association. They pushed with all their collective weight to funnel gas taxes to the creation of a vast network of interstates (Jackson, p. 248). Memorial Drive was constructed before 1930, but its use likely expanded after the Interstate Highway Act of 1956. The Act created a Highway Trust Fund: non-divertible money from federal gas taxes set aside for road construction (Jackson, p. 250). Another political force conspiring to connect roads like Memorial Drive to ever greater sources of traffic was fear over atomic attack during the Cold War. One of the reasons cited for the Interstate Highway Act was increased ease of evacuation in the event of a bombing (Jackson, p. 249). Memorial Drive was connected to the interstate highway system in the late twentieth century, becoming Highway 3A (Figure 7). The national automotive fervor played a large role in developing Memorial Drive into the artery it is today, and in shaping the surrounding neighborhood.

Figure 6: Automobile infrastructure and businesses, 1970 From the same Sanborn map from 1970, it is apparent that the Brookline neighborhood had become equipped to serve drivers. In one block, the map shows two parking garages (purple), a filling station (yellow), an auto sales and services company (green) and a used car lot. The rise of automobile infrastructure is testament to the prevalence of the car in the neighborhood. Source: Sanborn Atlas: Cambridge 1970. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Library.

Environmental history, demographics, and national culture and politics helped make the Brookline neighborhood receptive to the automobile, and the automobile, in large part, shaped the neighborhood into what it is today. Modern Brookline is a relatively low-density residential area bordered by the large artery of Memorial Drive (Figure 7). The road runs along the Charles River— a reminder of the original Charles River Parkway, designed for scenic leisure driving. Memorial Drive is now connected to an interstate highway system stretching up and down the east coast. Traffic is intense, especially where the thoroughfare meets Brookline Street at Boston University Bridge (formerly the Brookline Bridge). There is still no convenient access to public transportation for residents of the Brookline neighborhood. The area was designed for the automobile, and its infrastructure is still heavily biased in favor of the motorist driving through.

Figure 7: Magazine Beach and Brookline today Memorial Drive still runs through the site (purple), though Charles River Parkway is no longer delineated. As shown by the highway markings such as the one circled in red, Memorial Drive is now connected to a vast interstate system. The filling station in Figure 6 is now Magazine Beach Shell (yellow). Source: “Cambridge, Massachusetts.” Map. Google Maps. Google, 2015. Web. 06 Mar 2015.

Figure 7: Magazine Beach and Brookline today Memorial Drive still runs through the site (purple), though Charles River Parkway is no longer delineated. As shown by the highway markings such as the one circled in red, Memorial Drive is now connected to a vast interstate system. The filling station in Figure 6 is now Magazine Beach Shell (yellow). Source: “Cambridge, Massachusetts.” Map. Google Maps. Google, 2015. Web. 06 Mar 2015.

Works Cited

"Irish Potato Famine: Gone to America." The History Place. The History Place, 1 Jan. 2000. Web. 10 Apr. 2015.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford UP, 1985. Print.