What's New About New Media?

Lisa Gitelman and Goeffrey Pingree

In the short space of a current college student's lifetime, the internet

has gone from a specialized, futuristic system to the network that most

significantly structures how we engage daily with the world at large.

It is now obvious to anyone who uses a computer that intellectual exercises

as basic as reading the newspaper or doing research have become fundamentally

different activities largely because of the internet. So too have our

views of communication in general; the very notion of globalization, so

consuming in today's world, is predicated on the possibilities engendered

by a technology barely twenty years old. Such is the nature of "new

media." Computers, and the digital systems and products for which

they are currently a shorthand, are what most of us think of when we hear

the words new media. And why not? The world of computer hardware,

software, email, and ebusiness is for most of us the latest communication

and information frontier. Part of our experience of digital media is the

experience of their novelty.

Yet

if we were asked to think of other "new media," we might have

a harder time coming up with obvious examples. We would have no problem

citing instances of "old media": typewriters, vinyl record albums,

eight-track magnetic tapes, and the like. And we would have a point: These

are, from our current standpoint, old media. But they were not always

old, and studying them in terms that allow us to understand what it meant

for them to be new is a timely and culturally important task, an exercise

that in this volume we hope profitably to apply to media much older than

we are.

As

our title suggests, this collection of essays challenges the notion that

to study "new media" is to study today's new media. All

media were once "new media; and our purpose in these essays is to

consider such emergent media within their historical contexts—to

seek out the past on its own passed terms. We do so, in part, to counter

the narrow devotion to the present that is often evident today in "new

media" studies, a growing field whose conceptual frameworks and methods

of inquiry are heavily influenced by experiences of digital networks and

the professional protocols of the social science of communications. But

we undertake this inquiry mainly to encourage thinking about what "newness"

means in the relationships among media and societies.

There

is a moment, before the material means and the conceptual modes of new

media have become fixed, when such media are not yet accepted as natural,

when their own meanings are in flux. At such a moment, we might say that

new media briefly acknowledge and question the mythic character and the

ritualized conventions of existing media, while they are themselves defined

within a perceptual and semiotic economy that they then help to transform.

This collection of essays explores such moments in order to enrich our

contemporary perspective on what media are, and on when and how they are

meaningfully "new."

New

Media, 1740-1915 focuses on the two centuries before commercial broadcasting

because its purpose is, in part, to recuperate different (and past) senses

of media in transition and thus to deepen our historical understanding

of, and sharpen our critical dexterity toward, the experience of modern

communication. Indeed, we have marked the years between 1740 and 1915

as boundaries for our project because this period is crucial to understanding

how electronic and digital media have come to mean what and how they do.

The term media itself hails from precisely this period, as do the

structures of today's entertainment and information economies. Thus, the

media forms and practices studied in this collection are "new"

in a double sense: First, they newly receive the scholarly attention they

deserve; and second, they are considered within their original historical

contexts, their novelty years. In this, these essays provide a new perspective

on the meaning of "newness" that attends to all emerging media,

while they also tell us something about what all media have in common.

Yet our intention is not only to acknowledge the initial novelty of diverse media, but also to understand better how such media acquire particular meanings, powers, and characteristics. Drawing from Rick Altman's idea of "crisis historiography," we might say that new media, when they first emerge, pass through a phase of identity crisis, a crisis precipitated at least by the uncertain status of the given medium in relation to established, known media and their functions.1 In other words, when new media emerge in a society, their place is at first ill defined, and their ultimate meanings or functions are shaped over time by that society's existing habits of media use (which, of course, derive from experience with other, established media), by shared desires for new uses, and by the slow process of adaptation between the two. The "crisis" of a new medium will be resolved when the perceptions of the medium, as well as its practical uses, are somehow adapted to existing categories of public understanding about what that medium does for whom and why.

This collection, like

Carolyn Marvin's wonderful When Old Technologies Were New focuses

on such moments of crisis.2 While

it begins with the zograscope and ends in the heyday of silent cinema,

the volume does not aspire to cover all forms of media that emerged during

the years named in its title. Indeed, New Media, 1740-1915 addresses

only obliquely some of the more influential media of its period, print

media in particular. Most of the foliowing essays (unlike Carolyn Marvin's

work) focus on media—zograscopes, optical telegraphs, the physiognotrace—that

failed to survive for very long. They are, in Bruce Sterling's words,

today's "dead media."3

Yet because their "deaths," like those of all "dead"

media, occurred in relation to those that "lived," even the

most bizarre and the most short lived are profoundly intertextual, tangling

during their existence wlth the dominant, discursive practices of representation

that characterized the total cultural economy of their day.

Despite their inseparable

relations to surviving systems, however, failed media tend to receive

little attention from historians. "Lacking the validation that comes

with imitation," Altman notes, "unsuccessful innovations simply

disappear from historiographical record." His suggested corrective

for this excessive focus on, for example, "cinema-as-it-is,"

is an attention to "cinema-as-it-could-have-been" or "cinema-as-it-once-was-for-a-short-time-but-ceased-to-be."

New Media aims to apply some of this "could-have-been"

and "was-for-a-short-time" kind of thinking to past new media.

Because our understanding of what media are and why they matter derives

largely from our understanding and use of the media that survived—those

devices, social practices, and forms of representation with which we interact

every day—the importance of this kind of analysis is easy to overlook.

By getting inside

the "identity crises," by exploring the "failures"

(in some cases) of older new media, the essays in this collection will

help to counter what Paul Duguid has warned are two reductive "futurological

tropes" characteristic of the experience of modern media. The first

trope is the idea of supercession, the notion that each new medium

"vanquishes or subsumes its predecessors." From this idea follows

the current belief that in the digital age the book is doomed, or, according

to the peculiar auguries of earlier times, the conviction that typewriters

would replace pens or that radios would replace phonographs. The second

futurological trope is the idea of increasing transparency, the

assumption that each new medium actually mediates less, that it successfully

"frees" information from the constraints of previously inadequate

or "unnatural" media forms that represented reality less perfectly.4

This notion—that because of their greater transparency, newer media

supersede their predecessors—shapes both the experience and the study

of media today. Both of Duguid's tropes point to a frequent and shared

misconception, which supposes the value and (at least theoretical) possibility

of pure avenues of information, pathways that allow knowledge to pass

without interruption or interference-free of mediation.

This assumption creates

an interesting paradox. The best media, it would seem, are the ones that

mediate least. They are not, as we think of them, media at all. A new

medium therefore supersedes its predecessor because it is more

transparent. Few would disagree, for example, that a conversation with

a friend on the telephone allows for a greater exchange of personal, idiosyncratic

information than a dialogue conducted via telegraph. And to a large degree,

this thinking is persuasive. New media generally are more efficient

than their predecessors as means of communication. Yet there is more to

understanding what happens when people communicate through a given medium

than merely ascertaining what level of accuracy and amount of data the

exchange involves. This observation—that there is more than accuracy

and amount to any exchange—comprises a founding rationale for the

field of media studies, whether characterized aphoristically by Marshall

McLuhan ("the medium is the message") or more recently expressed

(and complicated) in Derridian terms, that the supplement—the

"specific characteristics of material media"—can never

be "mere" supplement; it is "a necessary constituent of

[any] representation."5 To

put it simply, looking for content apart from context just won't work.

Owing in part to the

linear progress unthinkingly ascribed to modern technology, media (so

offen referred to portentously as the media) tend to erase their own historical

contexts. Whether shadows in a darkened cave or pixelated images on a

luminous monitor, the media before us tend, anachronistically, to mediate

our understanding of their past. In the process, we lose any understanding

of the nuanced particulars of specific media. In part, we forget what

older media meant, because we forget how they meant. Once they emerge

and become familiar through use, media seem natural, basic, and therefore

without history. Of course we say "Hello?" when we answer the

telephone; of course we hear a dial tone when we pick it up to place a

call. Media seem inevitable in an unselfconscious way; we forget that

they are contingent. Alexander Graham Bell apparently wanted people to

say "Ahoy!" when they picked up the phone, but English speakers

settled on "Hello?" through the sort of unthinking social consensus

that attends the uses of all media. In a similar fashion, the dial tones,

12-volt lines, and modular jacks we use today all were shaped historically

by a complex of forces—technological, to be sure, but also social,

economic, and representational.

When we forget or

ignore the histories of each of these new media we lose a kind of understanding

more substantive than either the commercially interested definitions spun

by today's media corporations or the causal plots of technological innovation

offered by some historians.6 For

example, it is undoubtedly important to be able to note, as many scholars

have, how the invention of the cinema is linked to past practices of,

say, lecturing with slides, as well as how it predicts certain elements

of future practices. But what we often overlook are the kinds of things

that only a deep analysis of specific media cases can offer—how interpretive

communities are built or destroyed, how normative epistemologies emerge.

No medium new or old exists as a static form. Each case invites consideration

of numerous and dynamic political, cultural, and social issues. We might

say that, inasmuch as "media" are media of communication, the

emergence of a new medium is always the occasion for the shaping of a

new community or set of communities, a new equilibrium.

As we have suggested,

when a new medium is introduced its meaning—its potential, its limitations,

the publicly agreed upon sense of what it does, and for whom—has

not yet been pinned down. And part of the lure of a new medium for any

community is surely this uncertain status. Not yet fully defined, a new

medium offers possibilities both positive (one of our authors argues that

zograscopes helped construct polite society) and negative (another traces

the threat telephones posed to Amish communities). In other words, emergent

media may be seen as instances of both risk and potential. Today, for

example, the internet offers unprecedented possibilities for global villages

to coalesce, even while it threatens national or ethnic cultural traditions

and provokes anguished discussions of privacy in a "connected"

age. The same sorts of issues and anxieties surrounded the emergence of

other media. Indeed, it seems that technological change inevitably challenges

old, existing communities. The particulars of each case, however, are

valuable to our larger understanding of how media help to shape and reshape

culture.

Essays in this collection therefore examine media as socially realized structures of communication, where communication is culture—as James Carey explains it—a cultural process that involves not only the actual transmission of information, but also the ritualized collocation of senders and recipients.'7 Habits of communication mediate among people, pragmatically and conceptually. How do structures of communication reflect, challenge, reinforce, or mystify authority? How do they help imagine community? How do they help construct the aesthetic, or the mimetic? How do they orient the production and experience of meaning? How do they acquire and carry epistemological authority? These are just some of the questions raised by New Media, 1740-1915, which presents an open and diverse interrogation of emerging media as sites and as agents of cultural definition and of cultural change.

Ultimately, then, this is a book about framing: about how particular habits and media of communication frame our collective sense of time, place, and space; how they define our understanding of the public and the private; how they inform our apprehension of "the real"; and how they orient us in relation to competing forms of representation. We have selected the cases of new media that follow because they support these inquiries, casting such habits and media into relief, affording a vantage point from which better to see how cultural meanings are negotiated. But this collection is also about how we frame our own discussions of new media, for if this interrogation of emergent media is genuinely to illuminate our understanding of cultural definition and of cultural change, then we must be responsible about our own language. We must, in other words, acknowledge the key terms that are in play in our own discussions and attempt to define and deploy them as precisely as possible, not only for us now, but as they were used in earlier—and different—contexts.

In a work on new media,

terms such as media, culture, public, and representation

will appear often. But insofar as this collection seeks to understand

how the very idea of "media" evolves over time, we wish to employ

such critical terms with care and to bring questions about their use and

meaning squarely into the discussion itself as it proceeds. Our use of

the word technology is a good example. This term denotes, as Leo

Marx suggests, a necessary but "hazardous concept"; in this

book the term helps organize our thinking about the material, instrumental

conditions of modern life, yet for many readers it will also come larded

with less considered shades of meaning, assumptions about "Progress"

with a capital "P," or about technology as a preeminent cause

in history.8 Thus although we

rely on this term as an organizing device in this collection (the essays

proceed from technology to technology as a form of convenience), we also

wish to urge particular awareness of its hazards. Likewise with other

key critical terms. We know that we cannot exhaustively define "media,"

for instance, any more than we can completely pin down "culture"

(a notion that is, as Naomi Mezey observes, "everywhere invoked and

virtually nowhere explained"). Indeed, the cases we offer are about

culture as struggle and media as means in that struggle—a fabric

continually rewoven according to the interests of a given time and place.

Rather than fixing such terms and pinning them to moving targets, however,

we can frame our discussions of such pervasive concepts in self-conscious

ways that make our attempts to understand them more useful.9

In this volume we

offer cases that foreground the relationship between material and idea,

between what people think or believe or wish and what they feel with their

hands or see with their eyes or hear with their ears. Each of the essays

in the collection thus reveals, in some fashion, the strong relationship

between the contexts for some material, technological development, and

shifts in self-imagining and public understanding. Erin Blake, Wendy Bellion,

and Laura Schiavo, for example, consider the cultural meanings of perspective

and representation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by focusing

on the emergence of particular visual media (zograscopes, the physiognotrace,

and stereoscopes, respectively) and discussing how such media influenced

notions of individual identity. Patricia Crain, Katherine Stubbs, and

Diane Umble, by contrast, consider the cultural meanings of communication

by focusing on the arrival and adaptation of particular networked media

(optical telegraphs, electric telegraphs, and telephones, respectively)

that helped shape notions of identity in relation to larger communities.

All of the authors

engage new media as evolving, contingent, discursive frames, sites where

the unspoken rules by which Westerners know and enjoy their world are

fashioned. Such "rules" continually change, as new media become

situated and as such adjustments inevitably redraw the boundaries of communities,

including some individuals, and excluding others. Each new medium in effect

helps to produce a distinct public. Erin Blake's work on zograscopes,

for example, elaborates the idea that media assist in the construction

of the modern, Western public sphere, with its corresponding liberal subject

(today known as "the consumer"). Although she draws upon the

work of Jurgen Habermas, Blake ignores the often-mentioned circulation

of print media as the basis of the public sphere, instead looking to shared

social practices to understand how space is visualized. Her public is

literally a sphere; in her essay the bourgeois circles of eighteenth-century

London pop into 3-D as they enter the rational and impersonal arena of

public space via engravings glimpsed through new optical devices. This

new medium, according to Blake, helps the public to map itself. Wendy

Bellion's work on the physiognotrace depicts an American public that also

maps itself, but this public is one more complicated by its own experiences

of both graphic and political self-representation. By analyzing the American

reception of this profile or silhouette-tracing device, Bellion introduces

her readers to the cartography of the public sphere, showing the ways

in which new media are adapted within the very discursive conditions,

the very rules that they help to transform.

The rules for inclusion,

for drawing the boundaries of a public sphere, are less concealed in Patricia

Crain's essay, which examines how elaborate pedagogical systems designed

to resemble new media interpellated and located their subjects, in this

case by making them perform as optical telegraphs within larger, oppressive

systems of cultural replication. Like the tinfoil phonographs of Lisa

Gitelman's essay, optical telegraphs were more powerfully imagined than

they were implemented. Very few were ever built or used, yet the idea

of them circulated widely within the mentality, the public imagination,

of their age. Joseph Lancaster's classroom telegraphs literally disciplined

students, while even broader disciplinary measures may be read in their

controlling institutional contexts, as well as glimpsed in the titles

of early American newspapers like the American Telegraph [Conn.],

Hillsboro [N.H.] Telegraph, and Lincoln [Me.] Telegraph.

(None of these titles referred to electrical telegraphs, which had not

yet been invented.) In Benedict Anderson's formulation, the circulation

and ritualized consumption of newspapers like these assisted in the imagination

of a national community. What their titles and Lancaster's system suggest,

according to Crain, is that the imagination of media conditioned

the imagination of communities. Newspapers were imagined in circulation,

while optical telegraphs were outright imagined.

The perceived promise

of any new medium can have wide-ranging import, even if those promises

eventually go unfulfilled. To many observers, the tinfoil phonographs

of 1878 promised a new, more modern and immediate type of text, as recordings

might indelibly "capture" speech, without the intercession of

literate humans wielding pencils and paper. To other observers, the telephones

that spread to rural America around 1900 promised to enlarge the very

communication practices that self-defined Amish and Mennonite communities

themselves attempted to regulate. The wide popular reception of the first

promise, Lisa Gitelman speculates, challenged and helped to transform

vernacular experiences of writing and print, while raising questions about

the instruments and the subjects of public memory. The Old Order perception

of the second promise, Diane Umble shows, helped divide the aggregate

Amish and Mennonite population, for this perception coincided with the

ongoing regulation of intra- and inter-group communication and excommunication.

Although so often the focus of great attention and optimism, new media

are not, as these authors pointedly demonstrate, inherently benign; they

"bite back."10 They

thrive amid unforeseen consequences, often despite the best, most vigorous

intentions of their inventors, their promoters, their initial consumers,

or of the customary arbiters of public intelligence.

Nowhere are the unforeseen

consequences of new media more obvious than when they engage the culturally

authoritative practices of science, with its Enlightenment logic of rational

inquiry, objective experience, and accurate representation. The stereoscope,

for instance, emerged from the laboratory of British scientist Charles

Wheatstone as an optical instrument charged with explaining new theories

of vision. To scientists, the stereoscope could be used objectively to

demonstrate that vision is subjective, that the body can produce its own

experiences of depth when presented with the right cues. As Laura Schiavo

puts it, Wheatstone's stereoscope newly "insinuated an arbitrary

relationship between stimulus and sensation." Yet within the context

of commercially exploited and popularly apprehended photography, stereoscopes

were ultimately recast as mimetic amusements that tendered to consumers

an instructive and positivist model of how their eyes actually worked

to see the world as it really is. Vernacular discourse, in other words,

completely inverted the meaning of what the stereoscope "proved."

This inverted meaning helped to make the stereoscope popular, fueling

its commercial success as later nineteenth- and early twentieth-century

viewers consumed stereograph images as a form of virtual travel, appropriating

the world through pictures. At stake was far more than the prestige of

Wheatstone or the anti-intellectualism of the marketplace. The rules by

which the West knew the world had again come into play. The popularity

of stereoscopes helped redraw the very category of the "real,"

the consensual practices of "accurate" representation.

Assumptions about

what count as "rules," about what is "real" or "accurate"

or "normal," are no less at issue when new media are less popular

than stereoscopes were or less patently involved in describing normal

human perception. Media emerge and exist in ways that both challenge and

regulate notions of what it means to be human. Gregory Radick's essay

provides a clear-cut case. An amateur ethologist using the new medium

of recorded sound set out to learn the "language" of monkeys

and stumbled into one of the hottest debates in Victorian evolutionary

biology and linguistics: How is language uniquely human? In the course

of his research, Richard Garner's recording phonograph became an instrument

of knowledge deployed in various philosophic and scientific controversies—in

the tension between amateur and professional science, for example, or

in the dispute over whether abstraction or instinct founds thought and

language, or in discussions about the fundamental differences between

humans and animals. Garner worked on monkeys, but not without meddling

with the category of the human in two ways.. First, he raised anew the

definition of "Man" as "the talking animal"; second,

he wielded his phonograph as if it were a necessary—and better—third

ear.

As Garner's third

ear suggests—and as many authors have noted—new media can be

viewed as an endeavor to improve on human capabilities. Like a telescope

added to the eye of an astronomer or a microscope added to the eye of

a biologist, media can extend the body and its senses. Yet media do more

than extend; they also incorporate bodies and are incorporated by them.11

Media are designed to fit the human, the way telephone handsets or headsets

literally fit from ear to mouth, but also the way telephone circuits,

satellites, and antennas fit among their potential consumers, as integral

parts of communication/ information networks that literally shape what

communication entails for individuals in the modern age. And if media

fit humans, humans adjust themselves in various ways to fit media, knowingly

and not. Hands physically adjust themselves to different keyboards, different

keypads, and different pointing devices, while users subtly adjust their

sense of who they are. Some of these complexities may be glimpsed in Katherine

Stubbs's essay, which reads the history of electrical telegraphy in the

United States against and within the fiction that appeared in telegraph

trade journals. Published during the 1870s and 1880s, telegraph fiction

shows how new media can remain new through the agency of users. Amid ongoing

conflicts between labor and capital arising in part from the feminization

of the workforce, telegrapher-authors both used and represented the telegraph

as a means to explore identity in its relation to the body. In remaking

themselves, by negotiating gender-at-a-distance-and-by-telegraph, for

instance, telegraphers kept the character of their medium unsettled. In

other words, the "newness" of new media is more than diachronic,

more than just a chunk of history, a passing phase; it is relative to

the "oldness" of old media in a number of different ways.

As many have noted,

media often advertise their newness by depicting old media.12

The first printed books looked like manuscripts, radios played phonograph

records, and the Web has "pages." Ellen Gruber Garvey and Paul

Young each explore less familiar instances in which the new represents

the old in order to understand more fully the purchase that "newness"

has on the process of representation. As Garvey's account of scrapbooks

explains, scrapbook-makers took old media—literally the old books

and periodicals they had lying around—and made them into new media

in the form of scrapbooks. "Newness" in this case resonated

as much with personal and domestic experiences as it did with public and

collective apprehensions of novelty, posterity, or periodicity. Scrapbook-makers

tampered with the meanings of the scraps they collected by collecting

them, a practice Garvey refers to as "gleaning" and connects

to the composition and use of the Web today. Young, on the other hand,

presents a "telegraphic history of early American cinema," reading

filmic representations of telegraphs as only the most obvious link between

these two media, which seem, in retrospect, so different. As he explains,

these media shared a history as the subjects of technological presentations

and electrical spectacles. From the start, both became instruments of

news reportage, one in the transmission of stories on the wire (that is,

by telegraph wire services like the Associated Press) and the other in

the projection of stories onto the screen in "actualities" and

protonewsreels. "Newness" in this case resonated with emergent

conventions for representing narrative time, with experiences of currency

(of news as either new or old), and with new technology—all experiences

that transform our sense of time and space.

We hope these essays

will help to broaden the inquiry of media studies by calling attention

to the ways media are experienced and studied as the subjects of history.

No ten essays can do more than open the question, but opening the question

is crucial, we think, particularly as today's new media are peddled and

saluted as the ultimate, the end of media history. "Newness"

deserves a closer look. To that end, we include a brief section of documents

for discussion. These documents are not illustrations of our text as much

as they are artifacts that themselves point toward the rich and diverse

record available to media historians. We hope that they will suggest specific

historical and cultural meanings for media and promote a broader discussion

of media history. Like the essays in this volume, our captions to these

documents are meant as initial gestures toward that broader discussion.

We include them to remind readers that the history of media is an ongoing,

highly self-reflexive conversation about what we mean and—literally—how

we mean it.

Notes

1.

Rick Altman, "A Century of Crisis, How to Think About the History

(and Future) of Technology" (February 2000), and "Crisis Historiography,"

unpublished MSS., personal communication, May 1, 2001.

2.

Carolyn Marvin, When 0ld Technologies Were New: Thinking about Electric

Communication in the Late Nineteenth Century (New York: Oxford Llniversity

Press, 1988).

3.

Deadmedia.org. See Bruce Sterling, "The Dead Media Project: A Modest

Proposal and a Public Appeal," n.d., http://www.deadmedia.org/modest-proposal.html,

June 2001.

4.

"Material Matters: The Past and Futurology of the Book," in

The Future of the Book, ed. Geoffrey Nunberg (Berkeley: University

of California Press, 1996), 65.

5.

Timothy Lenoir, "Inscription Practices and Materialities of Communication,"

in Inscribing Science: Scientific Texts and the Materiality of Communication,

ed. Timothy Lenoir, 1-19 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998),

7-8.

6.

As Walter Benjamin cautions, "Newness is a quality independent of

the use value of the commodity. It is the origin of the illusory appearance

that belongs inalienably to images produced by the collective unconscious.

It is the quintessence of that false consciousness whose indefatigable

agent is fashion. This semblance of the new is reflected, like one mirror

in another, in the semblance of the ever recurrent. The product of this

reflection is the phantasmagoria of 'cultural history' in which the bourgeoisie

enjoys its false consciousness to the full"; The Arcades Project,

ed. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, trans., Rolf Tiedemann (Cambridge:

Harvard University Press, 1999), 11.

7.

James W Carey, Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society

(Boston: Unwin Hyman, 1988).

8.

Leo Marx, "Technology: The Emergence of a Hazardous Concept,"

Social Research 64 (fall 1997), 965-988.

9.

Naomi Mezey, "Law as Culture," Yale Journal of Law &

the Humanities 13, no. 1 (2001): 35. See also Raymond Williams, Keywords:

A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (New York: Oxford University Press,

1985).

10.

"Bite back" is from Edward Tenner's title, Why Things Bite

Back: Technology and the Revenge of Unintended Consequences (New York:

Alfred A. Knopf, 1996).

11.

The trope of bodily extension or prosthesis is not an anachronism applied

to new media. As James Lastra shows, it is one of two tropes that have

played a normalizing role in the emergence of modern media (the other

is that of inscription); Sound Technology and the American Cinema:

Perception, Representation, Modernity (New York: Columbia University

Press, 2000); see "Introduction" and chapter 1. See also N.

Katherine Hayles on "incorporating practices and embodied knowledge,"

199-207 in How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics,

Literature, and Informatics (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1999).

12. The remediation of one medium by another newer medium has recently been explored by Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin in Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999). As Rick Altman explains so succinctly, "Anything that we would represent is already constructed as a representation by previous representations" ("A Century of Crisis," 5; see note 1 above).

Documents (excerpt)

|

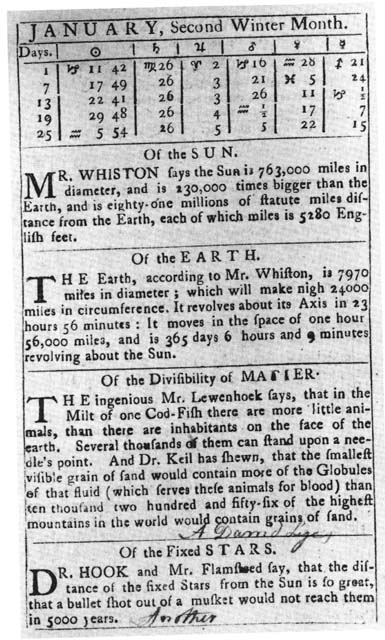

| Document A. Almanac Page with Reader's Annotations (1774) This page from Gleason's Massachusetts Calendar contains a reader's annotations, "A damed lye [sic]," and "Another," beside accounts of Anthony van Leeuwenhoek's microscopy and John Flamsteed's astronomy. The reader's skepticism calls attention to the complicated economies of belief that engaged eighteenth-century readers. While almanacs like Gleason's possessed defining preidctive functions, they also appealed to readers' sense of irony and doubt. What the reader doubted in this caseis science, though, not fanciful weather forecasts or astrology. Nature is itself newly and doubly mediated, first by the century's fledgling optics—microscopes and telescopes—and second by the printed page. Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society. |

|

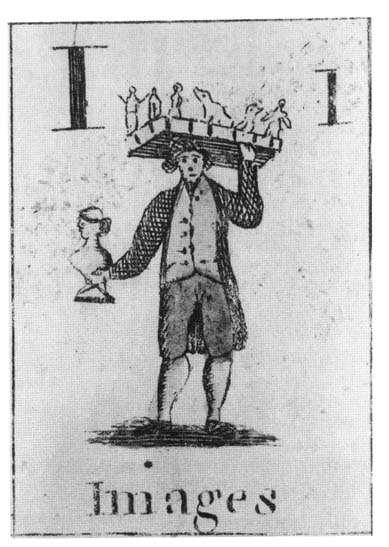

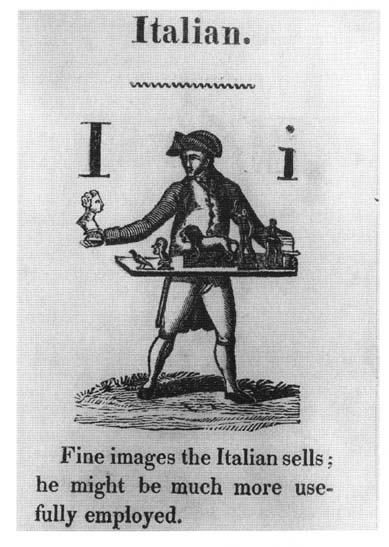

| Document B. Image Sellers from Published Street Cries (1810-17) Street cries were a popular print genre at the end of the seventeenth century, adapted for children at the beginning of the nineteenth century. They offer an interesting way to think about the character of literacy and the function of media. As instructional texts, the street cries promoted literacy, paradoxically, by romanticizing the oral, purporting to represent the appearance and repeated cries of itinerant peddlers in the cities of Western Europe and America. They gestured toward communities defined by earshot and integrated by the circulation of produce, goods, and services in the hands of outsiders, while they domesticate the peddler's voice by offering it for reiteration in the child's pronunciation of the alphabet. In these examples images circulate as commodities in the hands—and from the lips—of an Italian, while woodcut images (of images) circulated in the hands of publishers, parents, and children who wanted to connect the name and the image of the letter "I" with its phonetic identity. Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society. |

|

| Document B continued |

|

| Document B continued |

|

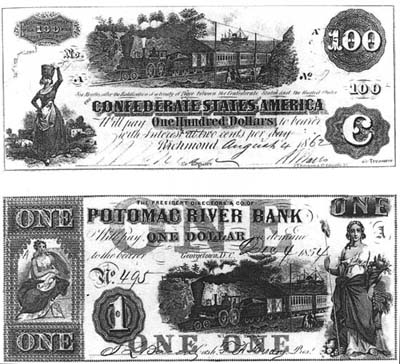

| Document C. Banknotes (1852, 1862) Before a uniform federal currency was established in the United States during the Civil War, more than a thousand individually state-chartered banks issued their own paper money. Banknotes were an intensely complicated form of media. They circulated locally, regionally and nationally, as they fluctuated in worth according to perceived and publicly reported redemption values. A wide variety of different engravings on notes helped to make them look valuable, or look real, though the duplication and reuse of images was common for legitimate as well as for forged notes. In these examples, the circulated notes with their recirculated images doubly represent the circulation of capital: the bills were supposedly backed by gold, even as they are fronted by the same tiny locomotive (with the same tiny telegraph line beside it) and the same tiny steamship, allegories of the dominant and intensively capitalized transportation networks of the day. Smithsonian Institution, National Numismatic Collection. |

documents

continued