| UPGRADING OF LOW INCOME SETTLEMENTS

COUNTRY ASSESSMENT REPORT |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SENEGAL | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

January 2002

The World Bank ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AFD Agence Française de Développement (French Development Agency) TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD OVERVIEW 1. PROBLEMS AND CONTEXT 2. CURRENT SITUATION 3. POLICY CONTEXT AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK 4. UPGRADING PROJECTS AND PROGRAMS 5. CASE STUDIES 6. LESSONS LEARNED 7. CHALLENGES AND PROPOSED NEXT STEPS ANNEXES Background to Study The Africa: Regional Urban Upgrading Initiative, financed in part by a grant from the Norwegian Trust Fund, is examining and selectively supporting urban upgrading programs in Sub-Saharan Africa through a variety of interventions. One component of the initiative focuses on distilling lessons from three decades of urban development and upgrading programs in the region. Specifically, the objective of this component is to assess what worked and what did not work in previous programs for upgrading low-income settlements in Africa, and to identify ways in which interventions aimed at delivering services to the poor can be better designed and targeted. As a first step, rapid assessment reports were commissioned for five Anglophone countries (Ghana, Namibia, Swaziland, Tanzania and Zambia) and five Francophone countries (Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Mali and Senegal). Each of the ten Country Assessment Reports provides an overview of the history of upgrading programs and policies in a given country and presents project or community specific case studies to identify lessons learned. Taken together, these ten reports offer insight into the nature and diversity of upgrading approaches in Africa and highlight some of the challenges in and lessons learned about delivering services to the poor. Acknowledgments This paper is one of a series of ten country assessment reports. The study was managed by Sumila Gulyani and Sylvie Debomy, under the direction of Alan Carroll, Catherine Farvacque-Vitkovic, Jeffrey Racki (Sector Manager, AFTU1) and Letitia Obeng (Sector Manager, AFTU2). Funding was provided by the Norwegian Trust Fund for Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development (NTF-ESSD) and the Africa Technical Department (AFT). Alicia Casalis and Chris Banes conducted the field work for the five Francophone and five Anglophone countries, respectively, and also prepared the draft reports for each of their five countries. Genevieve Connors provided extensive comments and was responsible for restructuring and finalizing the reports. Nine of the reports were edited by Lisa Van Wagner and the Zambia report was edited by Nita Congress. Senegal has been implementing a national urban upgrading and land legalization policy since 1987 in order to respond to the rapid and uncontrolled urban growth of its sprawling squatter areas. In the past, the Government applied a policy of successive slum evictions (deguerpissement). In 1985, there was strong reaction against the massive slum clearances implemented in Dakar, and as a result, the deguerpissements were stopped. Faced with the magnitude of the growing informal areas and the negative social reaction to the clearance policy, the Government decided to apply a new "urban upgrading and land legalization policy" with the support of the German Technical Cooperation (GTZ). This upgrading policy has over time become one of the main components of the national urban policy developed in order to resolve the strong demand for housing for the poor. Set up by a unit of the Directorate of Urban Planning (DUA) and the GTZ, the urban upgrading and land legalization policy was established in 1987, and has been regularly applied since. The policy was first used experimentally in the Dalifort neighborhood (1987-1990); was later set up as a national policy by two Presidential Decrees in 1991; is being extended to nine neighborhoods in Dakar; and was duplicated and adapted by other development agencies. Recently, new institutional and financial instruments have been created in order to sustain this policy. During this process, evaluations have been made; and the lessons learned from both successes and failures have been incorporated in the approach for new projects. 1. PROBLEMS AND CONTEXT Senegal is a coastal Sahelian country located in the western part of Africa with an estimated population of about nine million people (2001). Although overwhelmingly agricultural, Senegal has a growing industrial sector, one of the largest in West Africa. Nevertheless, the economy remains largely dependent on a single crop: peanuts. In the past, Senegal has suffered prolonged droughts, which have caused severe land degradation and have aggravated the chronic rural exodus. It is estimated that 47 percent of the Senegalese population lives in urban areas. Currently, 25 percent of Senegal’s urban zones have been illegally occupied, particularly in the Dakar area, where nearly 30 percent of the urban population lives in unplanned areas. The Human Development Index (HDI) rank Senegal 156 out of the 174 counties listed by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). 1.2 Urbanization Senegal’s annual population growth (1995-2000) is 2.6 percent and more than 4 percent in the capital, Dakar. Dakar is the largest city and the principal port and commercial center; it has 50 percent (about two million) of the total urban population of the country. The other cities in Senegal are much smaller than Dakar: the next largest are Thiès and Kaolock, which have populations of between 100,000 and 150,000 inhabitants respectively. After these, there are only three other cities in the country with more than 50,000 inhabitants. 1.3 Problems The rural exodus has been toward Dakar, in which the population of unplanned settlements grew by 45 percent between 1965 and 1972. The Dakar urban and industrial areas expanded to Rufisque and Thiès, and, very quickly, were ringed by informal settlements. Local authorities periodically applied the slum clearance policy and pushed the poor population towards the periphery. These areas are under-equipped and, because they are considered illegal, no infrastructure has been built. 1.4 Past and Present Responses A certain number of upgrading projects were carried out in Senegal with the approach set up by the DUA/GTZ unit, most of them in the area of Dakar. These included Dalifort, Arafat, Medina Fass M’Bao, Ainoumady, Sam Sam I, II, and III, Wakhimane, Gueule-Tapée, and Rail. The approach that was set up by the DAU/GTZ team during the first intervention was in the pilot quarter of Dalifort; from which came the name, “Dalifort methode.” The most recent intervention is a component of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) Program of Poverty Alleviation. The objectives of this project are to ameliorate the living conditions of the population of the municipalities of Guinaw Rails Nord and Sud (population total 150,000 inhabitants); to develop the capacities of intervention of the communities; and to reinforce the capacities of the local authorities. In this first phase, the investments in micro-projects are not a priority. This program started in 1999 with an initial budget of US$200,000. Beyond Dalifort, it is important to note the diverse organizations undertaking upgrading projects in Senegal. Further projects were undertaken in the secondary towns of St. Louis, Bignona, and Richal Toll. These projects were less important, and reached different levels of achievement. Two projects are considered as the most relevant: the Dalifort project, the pilot case to set up the DUA/GTZ method for slum upgrading in Senegal, and the project in Medina Fass M’Bao. A list of all the projects is summarized below.

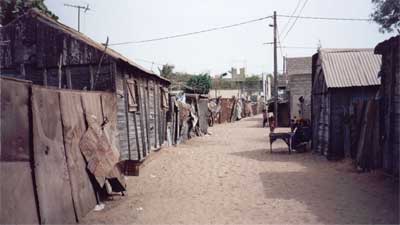

Accra Region 2.1 Low income settlement characteristics and location In 1952, Pikine was created to house the population which had been expelled from Dakar’s slums. This was the beginning of periodic interventions to clear slums in Dakar’s center and to relocate the poor population into planned plots on the periphery of the city. In 1969, 100,000 people lived in Pikine; today the estimated population is 1,000,000 and, as a result, Pikine has effectively become a satellite city of Dakar. Because informal settlements in Senegal are characterized by illegal land occupation, they are all underserved. However, the land tenure status and socio-economic characteristics of each neighborhood are quite different. Most of these characteristics originated with the displaced population as a consequence of the clearance policy before 1987, and grew with the immigrants arriving from different regions of the country. Dalifort, located between Dakar and Pikine, was chosen for the implementation of the DUA/GTZ pilot project. In Dalifort, approximately 7,000 inhabitants live in precarious wooden shacks. The project was replicated in Medina Fass-M’Bao which was created in 1970 by the population displaced by slum clearance from other areas. Medina Fass-M'Bao is a neighborhood of about 13,000 inhabitants east of Pikine, where most houses are built of permanent materials (cement blocks) surrounded by walls. 2.2 Profile of Low Income Settlement Residents In Dalifort, much of the land occupation was illegal. According to the administration, an “owner” was defined as someone who owned a house. Owners often possessed one or more houses which they rented. Those arriving in Dalifort had moved from other urban Dakar neighborhoods. In Dalifort, more than 70 percent of the households were made up of renters and 20 percent of the inhabitants were unmarried. Two kinds of renters could be identified: families that had lived in the quarter for a long time and rented houses belonging to a family member; and unmarried young people, who lived several occupants to a room. In 1987, 75 percent of the heads of household had an economic activity, most of them in informal activities. The socio-economic status of the inhabitants is strongly affected by their illegal land tenure and their precarious physical housing. 2.3 Land Ownership Three categories of land ownership exist simultaneously in the informal settlements:

For the first kind of ownership, the process of legalization is very simple: after the land division into plots, the Droit de Superficie (valid for 50 years) can be provided to the beneficiary. For the second kind, expropriation has to be carried out; and for the third, the land has to be first registered by the State as State land and then registered in the beneficiary occupant’s name. The expropriation and registration procedures are very long and complex. These can be done when the upgrading project is declared by a presidential decree to be a public utility. This process became possible after a decree in June 1991, which extended the notion of public utility for the expropriation of land illegally occupied. This important legal tool for the implementation of upgrading unplanned settlements policy is specific to Senegal in the Sub-Saharan African region. The beneficiaries of this land security policy are identified at the beginning of the project by means of a census and a public verification of all the people eligible for it. At the end of the procedure, and after payment, a genuine title deed is given. 3. POLICY CONTEXT AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK 3.1 Policy Context Between 1960 and 1987, the Government carried out large-scale slum clearance in the illegally-occupied areas. Despite the Government’s efforts to clear the informal settlements and to create housing alternatives through Sites and Services and planned housing programs, squatter areas continued to spread. The “deguerpissement” (clearance) policy of demolitions and displacement was socially and economically high-priced, as well as impracticable on a large scale. In order to deal with uncontrolled urbanization and to meet the strong demand for decent housing, the government has engaged in a series of three actions:

The World Bank financed four urban projects in an effort to provide low-income populations with affordable housing solutions between 1972 and 1997. These provided serviced plots, reinforced Dakar's urban institutions, developed local government capacities, and supported urban development. The Sites and Services Project was a large experimental project aimed at delivering serviced plots to 140,000 people in Camberene, a neighborhood of Dakar, and to another 12,000 people in Thiès. The experience of preparing this project provided important inputs to the now-classic document, “Sites and Services Projects: A World Bank Paper” (1974) . The second project was the Technical Assistance Project for Urban Management and Rehabilitation (Credit US$6 million). The project was approved in 1984 and closed in 1989. The objective of this project was to reinforce Dakar’s urban institutions. The third was the Municipal and Housing Development Project (US$46 million), approved in 1988 and closed in 1997. The major objectives of this project were to develop the capacities of the local government of the Greater Dakar area; expand the efficiency of the housing sector supporting the BHS; and improve the operation of the urban land market through the annual supply of a significant number of serviced and titled plots. The fourth urban project, the Urban Development and Decentralization Program (UDDP), was approved in 1997.* The aim of the UDDP was the reinforcement of municipal capacities in order to control urban development. The following projects provide support to housing and land municipal activities. The approach of the WB is that upgrading activities have to be included in municipal development activities and in the Contrat de Ville (City Contract). 3.2 Institutional Framework Institutional arrangements for managing urban development in Senegal are complex. Although local governments (through municipalities and CUD in the case of Dakar) have wide-ranging formal responsibilities, central government remains the key player in the sector. Four ministries are involved specifically in urban upgrading and land regularization:

Concessionary companies and the private sector—Société National d'Eau Sénégalaise (SONEES) and Société National d'Elecricité (SENELEC)—are also involved. Responsibility to upgrade informal settlements belongs to the Ministry of Urban Planning and Housing; however, the MUH can delegate this responsibility to a municipality or to another institution, either public or private (e.g., non-governmental organizations (NGOs), Fondation Droit à la Ville (FDV)). The administrative territorial reform of 1972 set up 37 urban municipalities; mayors were later elected with the decentralization policy of 1990. The responsibilities of municipalities were changed in 1996 with Law No. 96-07, which gave the municipalities more responsibility in urban development, in infrastructure, and in the provision and management of services. However, land use remains a centralized responsibility. Local autonomy is relative, since the municipal receipts are kept in the National Treasury, and the financial capacity of the municipalities is still very low. In addition, there is insufficient clarity regarding the division of responsibilities between the national and local levels. The municipalities have very few prerogatives concerning land affairs. In Senegal, there is no concept of a public or private municipal land domain. Law 96-07 presented the following principles:

It also enlarged municipal prerogatives related to urban development; the municipalities are responsible for:

4. UPGRADING PROJECTS AND PROGRAMS The DUA/GTZ Approach The DUA/GTZ program, which started in 1987 with the Dalifort pilot project, was designed and implemented with technical and financial support from the GTZ. The program relied on the involvement (both financial and physical) of the squatter population in the process of improving their living conditions. The main objectives of the program were providing security of land tenure; participation of the inhabitants; cost recovery and financial replicability; minimal infrastructure intervention; and management of the surrounding environment. The upgrading program was set up as an alternative to the “clearance” policy rejected by the population after the massive Dakar slum clearance of 1985. This program is described by the Senegalese Government and the GTZ in four different stages. 1. The Dalifort pilot project: “a laboratory” (1987-1990). 2. Enlargement of the scope and setting up a policy (1991-1992). 3. Strengthening the means and instruments within the framework of a nationwide approach (1993-1995). 4. Setting up an autonomous operator, the Fondation Droit à la Ville (1996-present). 4.2 Objectives and Approach The settlement upgrading and legalization policy in Senegal has five goals:

This new approach is based on two principles: keeping the population in situ, and involving the population in all of the steps of the urban upgrading and land legalization process. The DUA/GTZ approach has two main components: urban upgrading and legalization of land tenure. Upgrading consists of three phases:

As a part of urban upgrading, the DUA/GTZ approach has tried to ensure land security to inhabitants. Based on the hypothesis that the growth of precarious housing is not always due to poverty, but, instead, to a feeling of insecurity, improving access to land ownership is an important component of this approach, encouraging the owners to invest in their houses and to improve their living conditions. The principle for the DUA/GTZ approach is one plot of land per household. The land legalization process consists of attributing to each beneficiary a right of land occupancy (Droit de Superficie) in exchange for financial participation in the form of payment for infrastructure expenses and the land plot (based on an administrative scale for the sale of national land). 4.3 Land and Legal Aspects Land legalization is the main objective of the DUA/GTZ approach. This process starts with a study of land use and ownership in order to identify the beneficiaries. In the end, each household has the right to have one plot. A title deed called a Right of Land Occupancy (Droit de Superficie) is given to each household. The plot pricing depends on the area. The total price CFAF 3,000 per square meter (equivalent to US$9 per square meter) was divided into CFAF 750 (US$2-3) per square meter of land for the Dalifort pilot project (price fixed by the administration) and a contribution of CFAF 2,250 (US$ 6-7) per square meter to recover the costs of infrastructure. These infrastructure costs depend on the level of infrastructure chosen by each neighborhood. After payment for the plot, the beneficiary receives a right of occupancy for 50 years, without the option of selling the plot, and with the obligation of building a house in conventional materials in order to obtain a definitive land title. This regulation, however, has not been able to stop the sale of plots in the very active informal land market. 4.4 Design Principles and Guidelines for Upgrading The DUA/GTZ approach proposes minimal intervention in infrastructure, considering urban upgrading as a process and a challenge to successive generations. The project targets priorities and tries to be limited in scope and time. The respect of these criteria implies planning within the existing structures. If necessary, such planning must do without the norms of conventional city planning.” For the upgrading policy, a few changes in regulations had to be introduced by the Government in order to make possible exceptions to norms and standards and/or to allow some flexibility. Phases of execution: Methodology developed by the unit DUA/GTZ for the execution of the “urban upgrading and land legalization” projects:

Source: Groupe Huit/Poly consult In order to support the execution of the different phases of the projects of upgrading and land legalization, manuals have been prepared by the DUA/GTZ team to explain the activities for each phase. 4.5 Community Participation In the DUA/GTZ approach, “the population or its representatives have to take an active part in all stages of the process leading to the improvement of their surroundings: decision-making, implementation, financing, and facilities management. Once they have organized themselves as a ‘Groupement d'Intéret Economique’ (GIE: Economic Interest Group), the population defines its priority needs. All decisions are made with due concern for the financial means of the population. At the squatter level, the principle of solidarity must be a prerequisite. The improvement cost by square meter is equally allotted to all. 4.6 Financial Aspects In order to ensure financial replicability, the DUA/GTZ approach expected that beneficiaries would pay for their plots. Cost recovery is intended to ensure the financial replicability of the upgrading operation. After its creation, the GIE opens a bank account and collects its members’ shares and savings. Plot prices are estimated (see point 4.3), including participation in the infrastructure cost, land value, tax costs, and registration fees. Since the last two elements are a lump sum, the cost by the square meter is estimated according to the facilities chosen by the beneficiaries. “Although each household has to sign a deed of payment engagement, financial participation remains a considerable risk” according to the results reached. The resources collected for the payment for the land goes to the Treasury, and the cost-recovery for infrastructures goes to the FORREF. FORREF was created by decree in June l991 during the implementation of the Dalifort pilot project. Dalifort was given a grant by the German Cooperation; the funds collected by FORREF will be used for replication of the project in other areas. 4.7 Overview of Implementation Arrangements The slum upgrading program was executed by a DUA/GTZ unit funded by the GTZ established at the Directorate of Urban Planning. This DUA/GTZ unit is a centralized institutional framework and was justified as necessary until the present by Senegalese authorities in order to set up a national upgrading policy (during the three first steps of the upgrading program). For the next steps, an independent agency (FDV) is being set up to support decentralization and to reinforce the actions of local authorities. During the Dalifort pilot project, the Director of the Directorate of Urban Planning also served as the Director of the DUA/GTZ program. This institutional framework facilitated the following:

4.8 Operation and Maintenance The approaches tested by the Dalifort pilot project are based on the principle of a small initial contribution to the project, immediately followed by making the beneficiaries feel responsible, either by requiring their financial participation or by empowering them to manage the facilities themselves, for example, by managing public amenities such as lavatories and showers. The primary roads were transferred to the municipality for maintenance, and the water and the electricity supply system to SONEES and SENELEC. 5.1 The Dalifort Project The Dalifort neighborhood is on the border between Dakar and Pikine city. It contains 18 hectares and 600 plots; the population has grown from 7,000 to an estimated 9,000. The objective of the Dalifort pilot project was to develop a method to permit replicablility of the "urban upgrading and land legalization method" in other neighborhoods. The cost of the project is estimated at CFAF 300 million (US$900,000). The cost of technical assistance and personnel, which is not included in this amount, was very high in relation to the amount of investment. This technical assistance was in force for seven years. The Dalifort pilot project was executed by the DUA/GTZ team. A GIE (Economic Interest Group) was instituted at the level of the neighborhood as a base organization in order to facilitate the participation of the population in all phases of the intervention. As a result, a total of 600 stakeholders paid the CFAF 3,000 (US$9) to adhere to the GIE; however, it was a very long process, taking more than eight years. The contribution from the stakeholders for the costs of tertiary infrastructure (within the neighborhood: roads, stand pipes, sewerage facilities, lavatories, showers) is required, and goes to the FORREF. This contribution is not applied to trunk (primary) infrastructure. The resources from the payment by the beneficiaries for the “Droit de Superficie” go to the Treasury. The Treasury then gives the FORREF an amount (subvention or subsidy) equal to that received. This arrangement was established by a Government decree. The primary water and electricity supply, funded by GTZ, were transferred to the concessionaires SONEES and SENELEC for management and maintenance; the cost of individual connections was recovered directly from the consumer. The primary roads (trunk system) funded by the project (GTZ) were transferred to the municipality for management and maintenance. Recovery cost schema

FORREF was created in order to collect the payments for the plots and for the infrastructure created by the inhabitants. The amount collected was to be used for replication of the project. This was the base of the grant from the German Cooperation for the Dalifort project. According to the original device, FORREF, managed by the Senegal Housing Bank (BHS), should have received the contributions directly, bypassing the Treasury, thus avoiding the “unicité de caisse”(consolidated revenue) inherited from the French institutional system. This financing flow was never implemented as originally conceived. The FORREF was created by Presidential decree in 1991 and its financing mechanisms were reviewed in 1997 to respond to the legal framework of Senegal and to the conditions required by the GTZ. Of the resources collected from the beneficiaries, one part goes directly to FORREF (cost-recovery for infrastructure); and the other part goes to the Treasury. The cost recovery is estimated at 25 percent of the total cost. However, FORREF was not set up until 1997 — about five or six years after the operational phase started. This delay explains the low cost recovery of the Dalifort pilot project. FORREF is still not functioning as expected. The Dalifort project contained a total area of 18 hectares: 11 owned by the State and seven held by private owners. The State applied for a decree to expropriate the privately-owned land. Two decrees were issued: the first one declared the public utility of the intervention; the second ordered the expropriation of the area. There was an accord between the owners and the authorities permitting the State to pay the owners by exchanging the Dalifort project land for other State-owned plots within the same area. There were long discussions between the private owners and the DUA/GTZ team; 18 months after the project had been declared a public utility by decree, an accord was reached under which the private owners accepted a proposition before judicial proceedings began. The owners may have accepted these land exchanges because in many cases the original plots had a lower value than the ones received in exchange. In the judicial expropriation process, the first phase is consultation, which permits arrangements between the authorities and owners in order to diminish costs and the length of proceedings. In the case of the Dalifort pilot project, this accord facilitated the project because a disbursement from the government was not required. More than 600 planned plots were occupied by Dalifort stakeholders. Other important physical improvements included water supply and electricity connections installed by the SONEES and the SENELEC; roads to provide access to isolated blocks; individual and public sanitation; and garbage collection. This upgrading took three years and the inhabitants did the majority of the work. 5.2 Medina Fass M’bao Project The neighborhood of Medina Fass-M’Bao covers 40 hectares and is situated east of the Pikine Municipality. In 1993, the population was estimated at about 13,000 inhabitants, who occupied 1,300 plots (average of 200 square meters), without land titles. The Association Française des Volontaires du Progrès (A.F.V.P.) was the main implementing agency and the Agence Française de Développement (AFD) the financing agency. This neighborhood was created in 1970 by the population displaced (deguerpie) from other areas. The plots were irregular and under-equipped. Most of the inhabitants work in informal economic activities in Dakar. The DUA/GTZ approach (the Dalifort method) was replicated for Medina Fass M’Bao; however, some modifications were made in order to address the unique environment of this community. A methodology of participatory planning was developed by A.F.V.P. to establish the program with community participation. Primary infrastructure was designed by the technical team while secondary and tertiary infrastructure was decided during planning workshops with the community. The A.F.V.P. considered the GIE, the neighborhood community participatory structure, the key player for the success of the project; thus, the A.F.V.P. team prioritized the reinforcement of the GIE. The cost of the Medina Fass-M’Bao project of F.F. 20.3 million (equivalent US$3.63 million) was 60 percent financed by the AFD; 38 percent by the inhabitants (payments for right to occupancy of land and cost recovery from infrastructure); and 2 percent by the State (project support). Although the cost-recovery from the population should go to the FORREF, as a result of the postponement of the definitive set up of this fund, the contributions are still going to the bank account of the GIE. The F.F. 12 million (US$2.15 million) funded by the AFD was shared: F.F 7.7 million (US$1.38 million) for investments (hardware); and F.F 4.3 million (US$700,000) for A.F.V.P. (36 percent of total cost), the Social Intermediation Team, for training, information, and dissemination (software). Using an NGO (A.F.V.P.) as an operator was a new institutional framework in the implementation of the DUA/GTZ approach. The project Medina Fass-M’Bao was the first upgrading and land legalization intervention with a DUA/GTZ external operator. The project started in 1993 and closed in 1998. Several evaluations and documents have been written in order to analyze the Medina Fass-M’Bao project. For example, the French Cooperation set up a framework for the evaluation of the broad “Projet de Quartier” policy; the A.F.V.P. conducted an internal evaluation; and the AFD set up a new strategy for a new intervention in Senegal. Urban Upgrading In this quarter, 1,300 plots were designed, and 88 displaced stakeholders were resettled in the same area and financially compensated. This process was accomplished faster than in Dalifort. The primary roads were designed by the technicians of the project and the secondary and tertiary roads with community participation. A water supply system with a capacity for 850 individual connections was provided. The investment was limited by the low level of savings of the inhabitants (the investments were prorated according to savings). Legalization of Land Tenure The Medina Fass-M’Bao project was implemented with the DUA/GTZ approach for the legalization of land tenure. Obtaining the title deed was the last step in the upgrading and land legalization process; the beneficiary had to pay for the plot within five years of the start of the process. However, by then the plots had already been upgraded and the stakeholders felt that their land occupancy was more secure. Even if a financial commitment document had been signed by the beneficiary to the president of the GIE, the payments could still have been postponed. The acquisition of the right of occupancy did not prove to be a strong motivation for the beneficiaries to pay their shares of the costs involved. However, the stakeholders reached a level of assurance of land occupancy in a regularized area, and the risks of slum clearance altogether disappeared. The legalization of land tenure is considered a financial failure in terms of the low level of payments for the right to land occupancy and in terms of the long delays in the administrative processes. It is not, however, considered a failure in terms of giving land assurance to the inhabitants; the origin of this inconsistency can be found in the false assumptions that the beneficiaries would insist on having a “droit de superficie” in the short term and that acquisition of this right would serve as a motivation for payments. Cost Recovery The original objective for the recovery of CFAF 200 million (US$600,000) was not attained. In 1996, the recovery for infrastructure was estimated at CFAF 15 million (US$45,000), less than 10 percent. The principal reasons cited are the following:

The Approach The commitment to the GIE by almost all the inhabitants of the quarter is considered an accomplishment for the A.F.V.P. team. The GIE is still active today, three years after the closing date of the project. In addition, interventions are regularly pursued in order to improve the living conditions of the neighborhood. The president of the GIE has not changed since the project was initiated (elections take place every two years), and the upgrading approach continues to be implemented by the GIE and the population in order to develop the quarter. This is an important achievement for the project. The upgrading approach set up by the DUA/GTZ has been used as a reference for other upgrading projects. However, the complete replicability of the approach and the follow-up on a large scale seem, for some professionals, to be difficult, particularly because of the continuing need for technical assistance and the consequent high cost. The two main objectives in this approach, urban upgrading and land legalization tenure, are supported by community participation in all processes of the project, and by cost-recovery, which permits the replication of the intervention. Urban Upgrading

Land Legalization

Community Participation

Cost Recovery

Partnerships

7. CHALLENGES AND PROPOSED NEXT STEPS The establishment of an upgrading and legalized land tenure policy is a very long and complex process, which calls for specialized structures and mechanisms as well as economic and legal tools. The Dalifort pilot project carried out by the DUA/GTZ unit permitted the improvement of an upgrading approach for a small area. To extend the scope of this approach to other areas and cities is not only a matter of replicability; the approach needs to be consolidated and to formalize the human, technical, and financial means to ensure the continuation of the activities. Large scale intervention measures are being prepared by the Government with the support of the German Cooperation in order to ensure the sustainability of the present upgrading activities:

The Fondation Droit à la Ville (FDV): an Autonomous Foundation to support the decentralization process The Fondation Droit à la Ville was created by decree in December 2000 . This new organization is working to implement a large-scale upgrading project in the area of Pikine Sud. It will do so with much more autonomy and freedom than was previously possible. The Foundation will intervene as a project supervisor in different projects in order to respond in a more efficient way to squatter settlement upgrading in the context of decentralization. The objective of the foundation is to execute on behalf of the local authorities and the State the following activities:

The status of the foundation, according to the law, permits, in the framework of a private right, the implementation of missions of general interest and the raising of capital from private or public sectors. The initial allocation is F CFA 857 million from the first 17 public founder members (the State, the Municipalities of Dakar, Pikine, and Zinguichor) and private operators (Société Générale, l’AGETIP, the BHS, etc.). The Foundation will be under a double control system: technical control by the Ministry of Urban Planning and Housing and financial control by the Ministry of Economy, Finance and Planning. The Fondation Droit à la Ville will start its activities with the “ South Pikine Irregular” project, funded by the German Cooperation. The “South Pikine Irregular” large-scale upgrading project The “South Pikine Irregular” feasibility study ordered by the GTZ was finalized in 1998. The project was expected to start in January 2000; however, the status of the foundation “Droit à la Ville” was not approved until December 2000, and the recruitment of personnel started only in April 2001. In the project area of 700 hectares, there are 240,000 persons and an annual population growth of 8 percent. The total resources from the German Cooperation are CFAF 6 thousand million (US$10 million) for the first phase of five years:

The program has three phases of implementation, each one lasting five years. The upgrading will be disassociated from the land regularization procedures. The main priority is to build a minimum network of roads and individual sanitation systems; the second land regularization, which will be the responsibility of a specialized team (with experience in the preceding projects, e.g: Fondation à Droit à la Ville); and the third, community participation with increased participation of the municipal authorities. FORREF: a financial tool to assure replicability The functioning and limits of FORREF were explained above. The creation of the “Fondation Droit à la Ville” (FDV) as an autonomous operator and the KFW contribution of F CFA 500 million to start the South Pikine Irregular project are seen as an opportunity to enhance FORREF performance in the future.

A.F.V.P Restructuration Urbaine Quartier Medina Fass-M’Bao -Commune de Pikine. Coopération Sénégalo-Allemende. Prévention et Restructuration de l’Habitat Spontané- La Situation à Pikine. Fondation Droit a la Ville (FDV)- Règlement Intérieur. Adopté le 2 mai 2000 par l’Assemblée des Fondateurs. ———. Statut Préfaces par une note explicative. 2000. Groupe Huit/Polyconsult. Etude De Restructuration De Medina Gounass. Février 2001-. GTZ. Urban Upgrading and Land Legalization - Senegal. Ministry of Urban Planning and Housing. Jaglin, Sylvie et Alain Dubresson. Karthala-La régularisation foncière à Dalifort ou comment se passer des communes. Osmot, Annik. Pouvoirs Et Cités D’Afrique Noire. Korn, Pascale. Les Interventionsd en Quartiers D’habitat Precaire Dans Les Pays En Development- AFD- Mémoire Dess. 1999. Projet de Décret. Organisant la procédure d’exécution des opérations de restructuration et de régulation foncière des quartiers non lotis dans les limites de zones à rénovation urbaine. 29 juillet 1991. Sapin, Fanny. L’assainissement au service du développement? Jeux et stratégies d’intervention dans les quartiers précaires. IUG. Juin 1999. Secrétariat d’Etat à la Coopération. Evaluation De Projects De Quartiers Et Formulation De Reflexion Pour L’elaboration D’une Strategie. Février 1997. Urban Management and Rehabilitation Project. Performance Audit Report. Approx. 1993. World Bank. Development Project – Staff Appraisal Report. 1995. ———. Implementation Complementation Report. Municipal and Housing Development Project. Novembre 1997.

D.1: DALIFORT

D.2.: MEDINA FASS-M’BAO

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||