January 2002

The World Bank

AFTU 1 & 2

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

ADL Association de Développement Local

(Local Development Association)

AFVP Association Francaise des Volontaires du Progres

(French Association of Volunteers for Progress)

AGETIP Agence d'Exécution de Travaux d'Infrastructures Publiques

(Public Works Executing Agency of Cameroon)

ARAN Agence de Restructuration et d'Aménagement de la Zone Nylon

(Land Development Agency of Nylon Zone)

ARYNO Agence pour la Restructuration de Yaoundé Nord-Ouest

(Land Development Agency of Yaoundé North-West)

CAD Comité d'Animation au Développement

(Committee for Development)

CFAF Communauté Financière Africaine Francs

(African Financial Community Francs)

CFC Crédit Foncier du Cameroun

(Cameroon Housing Loan Bank)

DGTC Direction Générale des Grands Travaux

(General Administration for Large Scale Works)

EU European Union

FOURMI Fonds d'Appui aux Organisations Urbaines et aux Micro-Initiatives (Funds for the Support of Urban Organizations and Micro-Initiatives)

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GRET Groupe de Recherche et d'Echanges Technologiques

(Research and Technological Exchange Group)

GTZ Gessssellschaft fur Technische Zusammenarbeit

(German Technical Cooperation)

IPD Institut Panafricain de Développement

MAETUR Mission d'Aménagement et d'Etudes de Terrains Urbains et Ruraux (Special Agency for site and services development)

MINEP Ministère de l'Economie et du Plan

(Ministry of Economy and Planning)

MINFIN Ministère de Finances

(Ministry of Finance)

MINUH Ministère de l'Urbanisme et de l'Habitat

(Ministry of Urban Affairs and Housing)

NGO Non-governmental Organization

NTF Norwegian Trust Funds

OI Organisme Intermediaire

(Intermediary Organization)

SDC Swiss Development Corporation

SENEC Société National des Eaux du Cameroun

(National Water Utility for Cameroon)

SME Small and Medium Enterprises

SONEL Société National d'Electricité

(National Electricity Utility)

UNCHS United Nations Center for Human Settlements (Habitat)

UNDP United Nations Development Program

WB World Bank

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FOREWORD

OVERVIEW

1. PROBLEMS AND CONTEXT

1.1 The Country

1.2 Urbanization

1.3 Problems

1.4 Past and Present Responses

2. CURRENT SITUATION

2.1 Housing Characteristics and Location

2.2 Profile of Low Income Community Residents

2.3 Land Ownership

3. POLICY CONTEXT AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK

3.1 Policy Context

3.2 Institutional Framework

4. UPGRADING PROJECTS AND PROGRAMS

4.1 Overview of Initiatives

4.2 Approaches and Upgrading Typologies

4.3 Land and Legal Aspects

4.4 Design Principles, Standards, and Guidelines for Upgrading

4.5 Community Participation

4.6 Financial Aspects

4.7 Overview of Implementation Arrangements

4.8 Operation and Maintenance

4.9 Project Outcomes Evaluation

5. CASE STUDY

The FOURMI Program

6. LESSONS LEARNED

7. CHALLENGES AND PROPOSED NEXT STEPS

7.1 Follow-up on FOURMI I

7.2 Planning Activities for FOURMI II

ANNEXES

Annex A: Country and City Profiles

Annex B: Bibliography

Annex C: Contact Information

Annex D: Photographs

Annex E: Abbreviations and Acronyms

FOREWORD

Background to Study

The Africa: Regional Urban Upgrading Initiative, financed in part by a grant from the Norwegian Trust Fund, is examining and selectively supporting urban upgrading programs in Sub-Saharan Africa through a variety of interventions. One component of the initiative focuses on distilling lessons from three decades of urban development and upgrading programs in the region. Specifically, the objective of this component is to assess what worked and what did not work in previous programs for upgrading low-income settlements in Africa, and to identify ways in which interventions aimed at delivering services to the poor can be better designed and targeted.

As a first step, rapid assessment reports were commissioned for five Anglophone countries (Ghana, Namibia, Swaziland, Tanzania and Zambia) and five Francophone countries (Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Mali and Senegal). Each of the ten Country Assessment Reports provides an overview of the history of upgrading programs and policies in a given country and presents project or community specific case studies to identify lessons learned. Taken together, these ten reports offer insight into the nature and diversity of upgrading approaches in Africa and highlight some of the challenges in and lessons learned about delivering services to the poor.

Acknowledgments

This paper is one of a series of ten country assessment reports. The study was managed by Sumila Gulyani and Sylvie Debomy, under the direction of Alan Carroll, Catherine Farvacque-Vitkovic, Jeffrey Racki (Sector Manager, AFTU1) and Letitia Obeng (Sector Manager, AFTU2). Funding was provided by the Norwegian Trust Fund for Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development (NTF-ESSD) and the Africa Technical Department (AFT). Alicia Casalis and Chris Banes conducted the field work for the five Francophone and five Anglophone countries, respectively, and also prepared the draft reports for each of their five countries. Genevieve Connors provided extensive comments and was responsible for restructuring and finalizing the reports. Nine of the reports were edited by Lisa Van Wagner and the Zambia report was edited by Nita Congress.

OVERVIEW

The first main urban upgrading project in Cameroon was a multi-sectoral project started in 1984 in the Nylon zone in Douala. During the early years of implementation, this upgrading project was promoted through a well-implemented information campaign as an advanced experimental regional project. It was one of the first main upgrading projects in sub-Saharan Africa.

During the project design phase and the very first years of its implementation, Cameroon was enjoying a period of considerable prosperity. The preparation of the World Bank's (WB) First Urban Project (including the Nylon upgrading component) and the ambitious Second Urban Project were carried out in this context of economic growth. Under these favorable conditions, it was understandable that the government set high targets and initiated an extremely ambitious, costly, and complex project.

In 1986, however, the economic indicators suddenly plunged and a serious recession set in. Growth stopped, oil prices dropped, exports of farm produce declined, urban unemployment increased very rapidly, public finance ran out, and domestic and external debt rose steeply. For the Nylon project (funded by the government, the WB and the SDC) these difficulties meant that the government could no longer afford the project commitments. The WB decided not to extend the implementation period of the project and the project was closed in 1994 at the anticipated closing date, by which time, 62 percent of the available funding had been consumed.

The fact that the Nylon project remained unfinished had a negative impact on other urban upgrading projects and left a substantial information and experience gap1. However, the impact of the project was strongly felt in the neighborhood. Altogether the implementation period in the Nylon zone lasted more than 12 years.

Today, projects implemented under other institutional arrangements to improve living conditions in informal settlements do not require land regulation and legalization as prerequisites for upgrading activities. They are integrated into the decentralization framework and are focused on urban development through the implementation of micro-projects (infrastructure, services, facilities, and economic development). The FOURMI I project and its extension, FOURMI II, are examples of current urban upgrading efforts in Cameroon and are discussed in detail in this report.

1. PROBLEMS AND CONTEXT

1.1 The Country

Cameroon, located in western Africa, had an estimated population of 15 million in 2000 and annual population growth of 2.7 percent between 1995-2000. After independence, Cameroon experienced steady economic growth, social stability, and gradual national unification of the different provinces. The annual average gross domestic product (GDP) was between 7 and 8 percent from 1976 to 1981. From 1978 to 1982, oil represented about 63 percent of total exports, and replaced cocoa and coffee as the nation's leading export. However, oil prices fell in the mid 1980s, provoking serious economic problems. By the 1990s, there was a serious crisis concerning financial resources, in particular following the 1994 devaluation of the Communauté Financière Africaine francs (CFAF). As a result, the government drastically reduced its investments and subsidies in the urban sector. Since then, living conditions have deteriorated, particularly in the areas of education and health.

Presently there are new hopes for Cameroon's economic growth, based on the construction of the Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline. This project is expected to boost the economy to an estimated real GDP growth of 5.4 percent in 2001/02. According to the Human Development Index (HDI), Cameroon is ranked 134th out of 174 countries listed by UNDP in 2000.

1.2 Urbanization

Cameroon's urban population is approximately 49 percent (7.4 million) of the total population; thus Cameroon is considered a highly urbanized country by sub-Saharan standards. The average annual urban growth rate was 6.1 percent from 1970 to 1995; this has fallen to an estimated present annual growth rate of 4.1 percent. The urban system of Cameroon has two major poles: the main port and commercial center, Douala (population 1.4 million); and the administrative and political capital, Yaoundé (population 1.1 million). This bipolarity is specific to Cameroon; in most African countries, a large proportion of the population is concentrated in the single largest town (usually the capital). These two cities are followed by the secondary towns of Garoua, Bamenda, and Maroua, which have more than 200,000 persons each.

There is still a high rate of urban growth in Yaoundé (6 percent) and Douala (4.9 percent), with slower rates of growth in the intermediate towns, despite the fact that people are actually leaving the capitals for the main provincial towns because of the present economic situation.

1.3 Problems

The economic crisis in the mid 1980s has led to enormous needs in terms of infrastructure, public facilities, and various urban services. In 1988, urban poverty reached a level of 60 percent and about 70 percent of the population was living in unplanned settlements. The majority of peri-urban residents lived in poorly drained and poorly serviced areas. The water supply and sewage sector was particularly affected by the deterioration of public services. Consequently, health indicators have deteriorated.2 In addition, the rate of primary school enrollment declined from nearly 100 percent in 1980-85 to 62 percent in 1997.

1.4 Past and Present Reponses

The main objectives of the First Urban Project were to initiate a major upgrading effort in Cameroon in order to raise infrastructure standards to an acceptable minimum; to initiate land legalization; and to strengthen the institutional base for continued upgrading. The First Urban Project sought to upgrade one of Douala's worst squatter areas: the Nylon zone. The Second Urban Project was originally viewed as a continuation of the first, with some extension to civil works aimed at improving traffic conditions in Douala and Yaoundé. The project was also expanded to secondary cites. The WB has overall, considered the execution of the Second Urban Project largely unsatisfactory. The Second Urban Project was closed in 1994 and the loan was canceled before the objectives were reached.

This was the last upgrading of unplanned settlements in Cameroon which adopted a multi-sectoral approach and included land regularization and legalization. Other upgrading projects were financed by the African Development Bank in New Bell neighborhood and by the French cooperation in Douala, Yaoundé and secondary cities through local or international NGOs3.

Some other upgrading projects have focused on urban development through the implementation of micro-projects involving local authorities and communities. Examples of this approach are the Nkonldongo project in the Municipality of Yaoundé 4; and the FOURMI I and II (Fonds d'Appui aux Organisations Urbaines et aux Micro Projects) projects.

The urban development of the Nkonldongo project started in 1991 and closed in 1996, it was funded by the French Cooperation (F.F 1.5 million; equivalent US $270,000) and executed by two NGOs: GRET (Groupe de Recherches et d'Echanges Technologiques) and A.F.V.P, the association of French volunteers. This neighborhood of 8,000 inhabitants was representative of most unplanned areas, with major problems of management of urban services, particularly in water supply, drainage, and sanitation. The objective was to improve living conditions through the completion of micro-projects (a small bridge linking two quarters, stand pipes, drainage) with community participation. The lessons learned from this project have been validated by GRET and used to develop the basis of the FOURMI I program funded by the European Union in 1995. The FOURMI I participative urban development program, designed to provide funds for urban organizations and micro-projects, was initiated in May 1995. FOURMI II was started in April 2001.

2. CURRENT SITUATION

1.5 Housing Characteristics and Location

The rural migration to urban areas accelerated during the 1960s as a consequence of the country's economic growth. The new inhabitants occupied land which was managed by traditional customary chiefs. It is estimated that two-thirds of the populations of both Douala and Yaoundé live in dense residential areas that developed along main roads leading to the cities' administrative and commercial centers.

Douala is located on the Wouri River on the Gulf of Guinea. Large areas of the city lie only a few feet above the water table; thus, there is widespread flooding during the rainy season, particularly in the unplanned neighborhoods. Yaoundé is characterized by a topography that hampers urban upgrading. The area, composed of a series of valleys with steep slopes and flood-prone bottoms, makes the cost of the extension of infrastructure into these valleys very high.

In Douala's Nylon zone, only 6 percent of the houses were built with permanent materials. The water supply came from standpipes. There is a high rate of migration and an increasing demand by the population for services. An estimated 65 percent of residents are not connected to pipe-borne water, and 80 percent are not connected to sanitation facilities. Standpipes and a small number of private water connections are used by inhabitants; however, leakage and overflow from pit latrines and septic tanks has polluted the water table, which supplies water to wells and streams. This zone, which is vulnerable to flooding, has always been occupied by a population living in precarious houses without formal property deeds.

1.6 Profile of Low-Income Settlement Residents

There is no recent information presenting a complete picture of the unplanned urban areas in Cameroon although many urban socio-economic surveys were carried out in Douala, particularly in the Nylon area, during the implementation of the First Urban Project in the early 1980s.

A survey carried out in 1983,4 at the start of the Nylon upgrading project, found that 200,000 people lived in the 11 neighborhoods in the Nylon zone. The average family size was 6 members. The inhabitants were mainly allogènes (non-indigenous), most of them from the same ethnic group, which explained the high level of organization and the dynamism of the area. Of the residents, 80 percent had come from other neighborhoods in Douala; the majority had been displaced from the New-Bell neighborhood. Of these displaced inhabitants, 99 percent believed that they were owners of the land and thus had rights to permanent occupation. Most of the plots were purchased from the traditional chief. Of the total, 15 to 20 percent of the 200,000 inhabitants rented their homes. The average plot size was 150 square meters.

Only 12 percent of the heads of family were unemployed. More than 50 percent were employed in formal activities. Commerce represented 31 percent of the employment (informal and formal); transport, 18 percent; and the construction sector, 14 percent.

1.7 Land Ownership

Like other African countries, Cameroon suffers a profound right-to-land dualism between traditional and modern rights. There is an overlap among customary rights, land use rights, and modern rights established by State law. According to tradition, the notion of individual land ownership does not exist. Instead, the traditional "owners" are considered managers of the land, and the land itself belongs to the community or to a particular ethnic group. However, the traditional land rights and land occupation are not uniform throughout the country. In fact, there are several different traditional land practices as a consequence of earlier intermingling of people from different areas of the country. The notion of allogène (immigrant or outsider in the community) is very strong in land affairs, and the ceding of traditional land to an allogène is a very long and difficult process. For example, the zone of New-Bell in Douala is occupied by allogènes (the Bamilékés, who come from the western part of the country). They have claimed the right to this land since 1938, but the population is still unable to sell or rent the land.

According to the Law, land without formal property titles belongs to the State even though the traditional occupants claim it for themselves because of their traditional rights. This situation demonstrates the complexities involved in land use and land ownership conflicts; these complexities continue to be the main problems in land legalization for upgrading.

In 1974, Cameroon adopted laws which provided a framework for the transformation of traditional into modern tenure rights, as well as for state management of the undeveloped lands. According to these regulations, land is divided into three categories:

* Registered land belonging to the State,

* Registered private land (with a title deed),

* "Domaine National" (former traditional lands which are neither private nor belong to the State).

However, the limited implementation capacities of the Ministry of Urban Affairs and Housing (MINUH) have not allowed for effective enforcement of these laws. Only a small number of urban properties has ever been registered. Thus, the official plot production by the State is very limited, and the new unplanned urban developments have spread to the peri-urban area without rules and without official rights. In 1993 in Douala, between 40 and 60 of households owned the houses in which they lived, but fewer than 20 of the residents held registered titles to the land. There is an active market in untitled or illegally titled plots; this is also in part because of the absence of an updated cadastral survey.

3. POLICY CONTEXT AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK

1.8 Policy Context

In the early 1990s, with no change in the poor economic climate, major political and social changes started to occur. Political opposition emerged leading to a series of general strikes (ville morte) that stopped all public and private sector activity, paralyzing the economy, and highlighting the opposition's considerable influence, particularly in Douala. Multi-partyism and the legalization of opposition parties started with a multiparty election in 1992 after a nation-wide campaign of civil disobedience.

In 1997, the Prime Minister decreed a new urban strategy followed by the formation of a Committee of Coordination and Orientation on behalf of the Ministry of Urban Development and Housing (MINUH). The WB, the European Union (EU), and the Agence Française de Développement (AFD) funded the preparation for this strategy. This Committee's task was to prepare the plan of action and propose a framework for urban intervention by the donor agencies.

The strategy was approved in 1999 and is based on a partnership among three urban players:

(i) the State, responsible for national policy and regulations (the decentralized technical services have to support both the decentralization process and the decentralized local government);

(ii) the decentralized local authorities, responsible for urban management;

(iii) civil society and local associations, which are in partnership with the municipalities.

1.9 Institutional Framework

Urban management, including administrative, and investment functions, have been shared by the ministries and para-statal central offices; their provincial offices; the municipalities; and the regions. SONEL (Société Nationale d'Electricité) and SENEC (Société Nationale des Eaux de Cameroun) are responsible for urban services.

The responsibilities of the ministries and the decentralized local authorities overlap and are not clearly defined. The State continues to exercise tutelage over local authorities, and financial autonomy is far from being reached. The principle of "unicite de caisse" (centralized finances) compounded by the continuous financial problems of the State has had negative impacts on municipal functions6.

In 1987, the urban local authorities of Yaoundé and Douala were created. They have elected municipal councilors, but executive powers are exercised by central government representatives who preside over the council (Delegues du Governement). The first multi-party municipal elections in Cameroon took place on January 21, 1996 and the second in April 2001. The new Constitution of January 18, 1996 provides for two types of decentralized local authorities: regions and municipalities (communes).7

The Ministry of Urban Development and Housing (MINUH, Ministère de l'Urbanisme et de l'Habitat) is responsible for:

(i) implementation of the government's general policy on town planning and housing in towns with less than 100,000 inhabitants;

(ii) land registry and land management functions on government-owned land;

(iii) oversight of the Special Agency for Sites and Services Development (MAETUR, Mission d'Aménagement et d'Équipement des Terrains Urbains et Ruraux ).

The Minister of MINUH is assisted by a Secretary of State for issues of public-owned land and land registry.

The Ministry of Towns (MINVILLE, Ministère de la Ville), was created in 1998, with urban responsibilities in the provincial capitals and all towns with at least 100,000 inhabitants. This occurred two years after the new regulations to improve the decentralization process. MINVILLE is responsible for

(i) development and restructuring of large towns;

(ii) sanitation and drainage;

(iii) social development of neighborhoods;

(iv) public health and welfare, and supervision of waste collection and processing;

(v) professional and social integration of young people in difficulty; and

(vi) administration of roads in towns with at least 100,000 inhabitants.

Other ministries involved in urban development are The Ministry of Public Works (MINTP, Ministère des Travaux Publics), The Ministry of Public Investment and Regional Development (MINPAT, Ministère de l'Investissements Publics et de l'Aménagement du Territoire), the Ministry of Territorial Administration (MINAT, Ministère de l'Administration Territoriale); and the Ministry of Economy and Finances (MINEFI, Ministère de l'Economie et des Finances).

4. UPGRADING PROJECTS AND PROGRAMS

The Nylon Project in Douala

1.10 Overview of Initiatives

The name of the zone derives from the fabric of the same name, nylon, which enjoyed great popularity in the mid 50s. The first inhabitants of this area were surprised by the rapidity with which rainwater soaked the soil and compared it to the rapidity with which water wets nylon clothing, and called the area "Nylon." The Nylon zone was first established in the 1950s as a resettlement area for residents of the New Bell neighborhood displaced by road construction. This zone, which is liable to flooding, has always been occupied by a population living in precarious housing, with neither formal property deeds nor services. From 1971 onwards, the people of the Nylon area have organized themselves into neighborhood associations, the aim of which was to solve the most pressing community problems (security, installation of basic amenities, fight crime, etc.). At the same time, the area became one of the favorite topics for field studies undertaken by students at the nearby Institut Panafricain de Développement (IPD).8 When work to prepare the World Bank's First Urban Project was initiated, the Nylon zone already had a dynamic action committee and was known to IPD. This allowed the development of a dialogue between the WB and the action committee, which in turn led to the selection of Nylon as one of the project's main components.

The Nylon zone project was conceived as an integrated pilot project for urban upgrading. The infrastructure component of the project was co-funded by the government of Cameroon and the WB; and the facilities component by the governments of Cameroon and Switzerland. The technical and financial cooperation agreements signed between the government of Cameroon and the WB in 1983 and 1989 concerned the main infrastructure of the entire Nylon zone, including the first neighborhood pilot upgrading project. An agreement signed in 1984 with the Swiss covered public amenities and the support of artisans and small entrepreneurs. The SDC acknowledges that it was never a driving force in the project, restricting itself to funding some components without being really involved in implementation.

Subcomponents of the Nylon Project in Douala were:

* Primary Infrastructure in Nylon: major roads, drainage, refuse bins, street lighting, and water for the entire 600 hectares of the Nylon zone (11 neighborhoods) to ensure basic access, improve availability of water, and solve major drainage and garbage problems;

* Major Drain of Mgoua: the main drain of the Nylon watershed;

* Pilot Neighborhood Upgrading: as the first phase in a neighborhood of 50 hectares for a much longer-term (10 years) project of 11 neighborhoods;

* Housing Loans for the Pilot Upgrading Area: 600 loans for plot purchases and home improvements for residents in the pilot neighborhood;

* Community Facilities: primary school classrooms, public health facilities, community centers, and sports fields;

* Retail Market: area of 10,000 square meters;

* Artisans Assistance: technical and managerial assistance to artisans and small entrepreneurs in the Nylon zone.

1.11 Approaches and Upgrading Typologies

Initially, the entire multi-sectoral upgrading project planned to cover 600 hectares, plus 300 hectares for a new resettlement area for displaced inhabitants. The original plan for upgrading began with major infrastructure work in order to rapidly build road access and bring community facilities up to an acceptable minimum. This was to be followed by a much more time-consuming process of completing the upgrading through the provision of secondary and tertiary infrastructure, and by the regularization and legalization of land tenure. In the project design, the plan was for a first stage pilot project in 50 hectares (13,000 residents) before the complete program could be carried out.

The following amenities were built: the Madagascar Market; two health centers; a youth center, subsequently turned into a mothers and babies welfare center and then transformed in hospital; a small health center; two schools; a social center; a playground for children; and a library. In addition, a cemetery, entirely funded by Cameroon, was also built. Work was carried out where the sites were ready, land was available, and demand was strong. The amenities were due to be handed over to the Cameroon authorities once completed. Their construction was supposed to fulfill two conditions: work had to be organized so as to involve local companies as much as possible; and priority was given to neighborhood merchants. A management committee was to be set up for each amenity in order to supervise the use of the premises.

1.12 Land and Legal Aspects

The 50 hectares of the upgrading pilot project belonged to the national domain (with the exception of 3.8 hectares). Land was managed by MAETUR alongside the Land Development Agency of Nylon (ARAN). The plan was that MAETUR/ARAN would be responsible for the realignment of plots (reblocking) with community participation, and would eventually provide the beneficiaries with provisional land titles. These agencies would also provide compensation and resettlement for those former residents displaced by upgrading activities. The Government initially forecasted to buy 30 hectares for the resettlement of the displaced population. (See Section 2.3 for further background)

1.13 Design Principles, Standards, and Guidelines for Upgrading

The infrastructure component formed the backbone of the project, both in terms of design and budget. The majority of WB and government funding was allocated to the construction of a primary road network comprising major thoroughfares intended to form a new main road network for Douala. As technical project studies advanced (at a time of high economic growth), the authorities and design offices constantly raised standards, both for the size of the structures and for construction techniques. This design inflation effectively turned the project into an infrastructure project. This of course was contrary to the express intention of the initial project aims. The infrastructure component was implemented by ARAN under the responsibility and supervision of the WB.

1.14 Community Participation

The people of Nylon neighborhood organized themselves and set up an action (animation) committee, first known as "Animation" and later as ADL (Association de Développement Local). The project established the notion that an action committee should be consulted at all stages of the project, from preparation to execution, through community representatives on the MAETUR/ARAN Steering Committee.

1.15 Financial Aspects

The preparation for the first Urban Project was extensively drawn out, lasting from 1977 to 1983. A loan was finally approved in 1983. Of the total cost of US$54.7 million, the WB loan covered US$20 million (36 percent), the SDC loan covered US$5.5 million (10 percent), and the Government, US$29 million (54 percent).

The principle of partial cost recovery was established according to the recommendations of the WB. Cost recovery was expected to cover the expenses for studies and for plot demarcation; as well as some serviced plots. A separate series of public amenities (Community Facilities and Madagascar Market)10 were funded jointly by the SDC and the Cameroon government. Switzerland was to fund 81 percent of the cost and provide two technicians to supervise the work and the Cameroon government was to fund the remaining 19 percent.

The cost overrun was estimated at 35 percent (US$13.1 million financed by the Second Urban Project and an increase of US$2.7 million from the SDC). For the Nylon pilot project, the overrun cost was estimated at more than 56 percent. The SDC evaluation presented an overrun of almost 50 percent of the cost for the facilities. The Madagascar Market finished at 200 percent over the original cost. SDC financed community facilities and technical assistance; the WB funded hardware components. The WB and SDC activities in Nylon zone were implemented, for all practical purposes, nearly independently. The Second Urban Project, in the amount of US$146 million, was approved in 1988, and was closed in June 1994. Only US$90.99 million of the loan was disbursed; the remainder, US$55.01 million, was canceled.

1.16 Overview of Implementation Arrangements

The Ministry of Urban Development and Housing (MINUH) was responsible for project implementation; MINUH's Directorate of Urban Development and Housing (DUH) was designated project coordinator; and MAETUR (located in Yaoundé) was named the implementing agency for the primary infrastructure and upgrading components. The project established a special contracting agency in Nylon, the Agence de Restructuration et d'Aménagement de Nylon (ARAN) within MAETUR. Originally ARAN was given responsibility for implementing the entire project. However, some of ARAN's tasks were monitored and supervised by the WB. Other tasks, in particular the public amenities funded by SDC, were directed by SDC overseas volunteers seconded to ARAN. ARAN was well suited to building infrastructure but quite incapable of handling institutional development tasks. ARAN management was responsible for contacts with the local population. The preferred representative all the way through the project was the local community group Animation. Almost exactly the same people have represented this organization from its start in 1971 to the present day. In practice, the interaction between the three major funding agencies - Cameroon government, WB and SDC - was complex and confusing in terms of definition of responsibilities.

1.17 Operation and Maintenance

Project maintenance was organized in accordance with the regulations of the government of Cameroon and other established institutions. For example, the maintenance of the market is the responsibility of the municipality and the water supply and electricity of SNEC and SONEL. However, with the current economic crisis, maintenance is not assured. Furthermore, the responsibility for maintenance of the drainage infrastructure is not clearly delineated between the State and the local governments, while responsibility for primary infrastructure is shared by the State and the local governments.

1.18 Project Outcomes and Evaluation

Outcomes

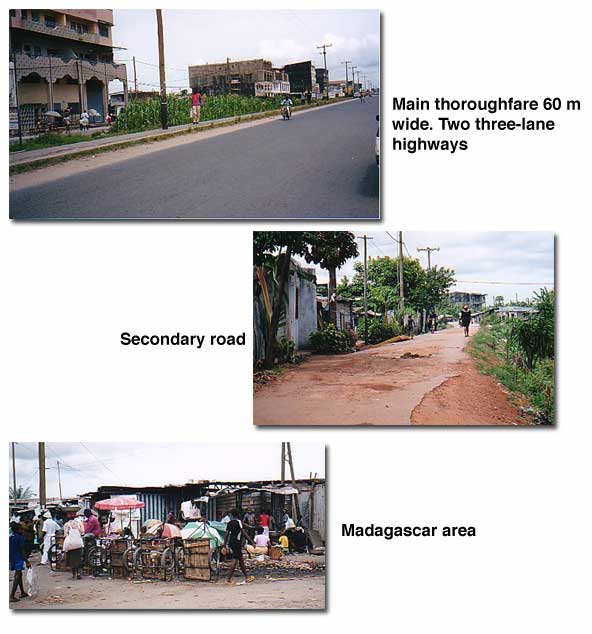

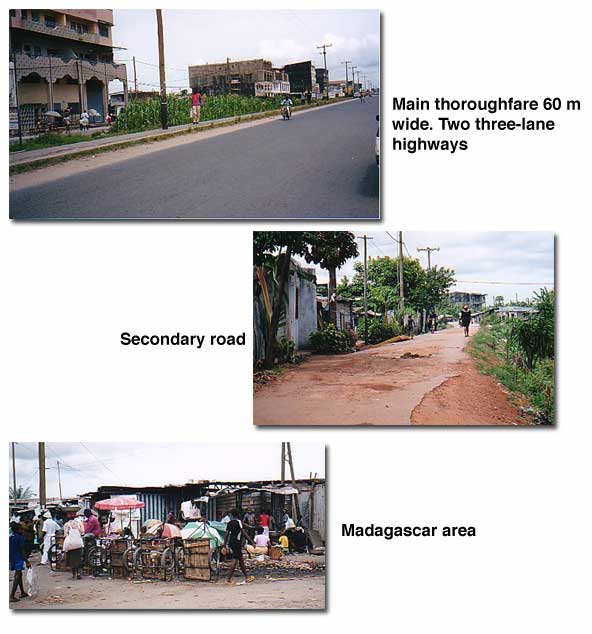

Primary Infrastructure. At the start of the project, the planned network fit into a series of new thoroughfares covering the whole urban area of Nylon. As a result, the main roads were designed to serve not as neighborhood streets but rather as parts of a regional network of main roads. The standards selected were correspondingly very high. The main thoroughfare was 60 meters wide, comprising two three-lane highways with a central median. As long as funds were available, the roads were built without any attempt to adapt them to the emerging economic conditions. The primary infrastructure component necessitated the departure of an important number of families. The roads have been handed over to Communauté Urbaine de Douala (CUD), which does not have the means to maintain or repair them. The road surface is currently in a poor state of repair.

Madagascar Market. This market was well built and absorbed over half of the available SDC funds. Local contractors trained by SDC played a significant part (more than 15 percent) in its design and construction. Despite these successes, the market has not fulfilled its expected role, as it is too expensive for local shoppers looking for essential everyday products. In addition, the public transport service is too inconvenient to attract shoppers from the city center, who want more centrally located shopping opportunities. These structural reasons explain why the Madagascar Market management company has failed to break even and why maintenance work is neglected.

Community Facilities. The various buildings for the small public amenities (schools and health centers) funded by SDC are also well built. They were handed over to the relevant bodies, the Ministries of Education and Health. This success shows that it is easier to succeed with small facilities that correspond to clearly stated demands and that are built to standards close to those to which people are accustomed to.

Pilot Neighborhood Upgrading. The WB and Cameroon Government project was based on two criteria:

* all the displaced families should have access to a serviced plot (subject to payment) and should be able to obtain a loan to build a house;

* the zone should be restructured in an integrated way; in other words, access roads and drains should be built, plots laid out, and the remaining occupants should be able to purchase their plots through the official market, obtain land titles and loans to improve their dwellings, and thus achieve permanent status as land owners.

The Pilot project failed in the land legalization process; the population paid for the plots but never received land titles. These were very important to the "allogenes" inhabitants of Nylon, which was considered an illegal neighborhood.

Housing Loans. In the rest of the zone, there were to be loans for the poor to enable them to improve their dwellings. This scheme, undertaken by ARAN, only partly achieved its objectives during the first few years. It was then almost completely stopped when it became clear that the CFC (Credit Foncier du Cameroun) funds, confiscated by the State, were no longer sufficient to provide loans; that land titles were not being allocated to those entitled to them (poor displaced householders could not afford the price of plots without monetary compensation)11; that infrastructure was not being built in the resettlement areas; and that ARAN no longer had the means to reinvest the money from the first sales in order to develop various other areas. For want of grants to cover operating costs, ARAN had used the money to cover its own expenses.

Artisans Assistance. These activities, supported particularly by the SDC, took various forms:

* Support for SMEs (Small and Medium Enterprise): help small construction companies by contracting with them for the construction of the Madagascar Market and the small educational and medical amenities.

* Support for Espace-Métiers: encourage the setting up of "trades centers" in unoccupied or unrentable premises in the market. This enabled artisans to improve their services, form groups and integrate in the official economy, and exhibit their work. This action was only slightly successful and, as with all similar "springboard organizations," the best people have moved on after achieving a degree of self-sufficiency (which in fact was the aim).

Evaluations

* The infrastructure network, as planned by ARAN, never operated properly because it was never completed. The ends of the main roads through the neighborhood were not finished, awaiting the completion of the Second Urban Project. Connections to the rest of the road network, particularly towards the city center, were always extremely poor. The main roads were built to unrealistic standards.

* One of the most important unresolved issues at the end of the project was that almost 2,000 families had to be displaced during the initial phase, and 3,700 families in all had to be displaced by the entire project. This component was an almost complete failure. No more than 20 percent of the 3,700 displaced families were properly resettled. Some of these families never received the monetary compensation as agreed upon prior to the project's start (more than 200). The WB reacted vigorously to the resettlement problems, and this point was central to the decision to cancel the loan. The WB considered the lack of Government commitment to resettlement arrangements to be at the root of the problem; these resettlement problems persisted until the project closed in 1994.

* The project's interpretation of Cameroonian land rights was that only the displaced households that possessed formal land title could receive monetary compensation. A limited number of families received the monetary compensation in order to pay for the plots and to build houses in the new resettlement areas.

* Similarly, the neighborhood-upgrading component was executed in a fairly technocratic way in terms of the plans (regular plots) and standards adopted. The determination, for instance, to go ahead with the construction of oversized access roads also did unnecessary damage to the existing urban fabric: the tarmac-covered roads were at least four meters wide, equipped with twin 60 cm concrete gutters. This overestimation also resulted in a further increase in the number of displaced families, which substantially reduced the merits of the upgrading project.

* The rapid deterioration of the completed infrastructure not only wasted resources, but also had an inhibiting effect on other components. For instance, there is currently a stark contrast between the very large Madagascar Market and the fact that it is almost inaccessible during the rainy season; and between the design of the health infrastructure network (health centers in the various neighborhoods and a single neighborhood hospital to which serious cases are sent) and the fact that several of the centers cannot be reached by ambulance or taxi during the wet season. These examples show that urban projects constitute a whole and that involvement in some components without involvement in others presents a real risk.

* During the Nylon project design, Cameroon enjoyed a period of considerable prosperity. In this overall context, the preparation of the Nylon project must be seen as involving a different, non-conformist approach, simply because it was based on the idea of rehabilitating and developing a shanty-town rather than demolishing the existing buildings and replacing it with new ones. Despite this approach, as soon as the feasibility study started, the project shifted to become part of the major national infrastructure. This shift of focus became even more noticeable during the operational study phase which coincided with the peak of Cameroon's fortunes and further raised standards, with reference to the excessively optimistic forecasts in the Douala master plan.

5. CASE STUDY

The FOURMI Program

Fourmi is the French word for ant. This acronym was developed to illustrate the aspects on which the approach is based: the promotion of micro-projects and small urban organizations for urban development.

FOURMI I was initially planned for three years (May 1995 to May 1998). The project was extended to the end of 2000 and had a total budget F.F 12 million (equivalent to US $1.7 million) of which 50 percent was for investments funds, 25 percent for capacity building, and 25 percent for the social intermediation team. The program received technical support from GRET in the form of coordination, management, and follow-up.

FOURMI had three priorities:

(i) the promotion of public health: drinking water, sewage, air quality, waste disposal, household waste;

(ii) the improvement of living conditions: park areas, health care, housing, and public facilities;

(iii) the conservation of natural resources: ecosystems, farmland, forests, non-renewable resources and energy.

The five towns where the program was first introduced were chosen, in the case of Douala and Yaoundé, because they have severe urban management problems, and, in the case of Bamenda, Bafang, and Bafoussam, because they were the focus of pilot projects started in 1992 with funding from the Coopération Française.

The general aim of the FOURMI I program was to improve the urban environment in the disadvantaged neighborhoods of the main towns of Cameroon through micro-projects that would:

* Create infrastructure on the basis of what the population felt was needed, with the support of intermediate organizations;

* Organize the participation of the population so that the national project operator, with a committee to select the micro-projects, could have a representative who was recognized by the population concerned;

* Inform local authorities of the initiatives in the different neighborhoods and seek their technical and financial support.

* Obtain concrete participation from the whole population through subscriptions from inhabitants representing a share of the costs of the overall budget for the project, with the rest coming from funds made available by the European Union.

FOURMI is not a thematic program; all demands are admissible if the micro-project is supported by a group of players in a neighborhood. The only demand is that project costs remain between CFAF 500,000 (US$500) and CFAF 20 million (US$40,000).

Four principles were established to promote local economic development.

* Develop a demand-responsive approach;

* Favor integrative rather than sectoral approaches to interventions;

* Establish relationships between the different players who intervene in the towns;

* Create a component for negotiation, thus providing conditions which give to the population the right to make known their views about all the matters related to neighborhood development.

The Committee for Development (CAD, Comité d'animation au développement) was the focal point for FOURMI I, and was defined as a group of volunteer inhabitants working in order to ameliorate the quality of life of the neighborhood. These representatives are elected by the inhabitants. CAD organized the population in order to define priorities for the neighborhood and to mobilize the means for the micro-projects. The local associations are intermediary structures (OI, Organisme intermédiaire) which intervene in the organizations of the urban population, such as Douala'Art in Douala and CASS (Centre d'Animation Sociale et Sanitaire) in Yaoundé.

The EU funded FOURMI I and II; for the first, the program operator was GRET; and for the second, CERFE, an Italian non profit group.

The project had two components with different financial approaches for social and economic micro-projects:

- Social micro-projects: subsidies from 65 up to 90 percent (according to the importance of the project) of the cost of micro-projects to provide infrastructure and public facilities in different neighborhoods of Douala, Bafang, Bafoussam, Bamenda, and Yaoundé. The participation demanded was in cash (FOURMI I).

- Economic micro-projects: funding in the form of loans for projects presented by small businesses for a maximum of three million CFA francs (US$6,000). Priority was given to support existing activities in manufacturing, processing, and services. This component, representing 15 percent of the program's investment fund, was experimental and provided a basis for assessing the economic and social link by focusing on the neighborhoods that also received social components.

*CASS: Centre d'Animation sociale et sanitaire

**Integrated Development Foundation

***Centre de développement des communautés villageoises

****Centre d'éducation populaire et d'animation pour le développement

OI: Organisme Intermediaire (Intermediary Organization)

CAD : Comité d'animation au développement (Committee for Development)

Source: Développement participatif urbain au Cameroun- GRET, 1998

The micro-projects considerably improved living conditions in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Moreover, micro-projects are an effective way of encouraging self-help The success of FOURMI, for the EU, can be measured by the fact that there was no shortage of applications for investment funding for micro-projects, even with a graduated rate.

So far, FOURMI has laid the foundations for a decentralized development program by showing urban populations how the existence of a fund for financing micro-projects can be an effective way of alleviating poverty. The program has demonstrated the feasibility of mobilizing human resources and has shown local authorities that the population is ready to contribute to the provision of infrastructure if they have confidence in the way things are being done and if projects are properly managed. This willingness on the part of the population is a sign of new long-term prospects for cooperation between the authorities and the population. The program was started at a time when the political situation was still fragile, especially in terms of conflicts between political, administrative, and social forces, and when very few NGOs were working in urban areas.

However, over 340 social micro-projects were selected (40 percent for local road systems; 28 percent for drinking water supplies; 21 percent for sewage; 7 percent for rehabilitation of buildings; and 4 percent for other projects). The average contribution from the population was 560,000 CFAF (US$1,120) per project, representing 24 percent of the average cost of the projects and; 45 small businesses received funding.

FOURMI II, an extension of FOURMI I, started in April 2001. The program objectives are the same:15 to improve the urban environment in the disadvantaged neighborhoods of Yaoundé and Douala by supporting basic efforts to involve the inhabitants in decisions concerning their own development.

Specific objectives components are:

* Investments: Material structures to improve living conditions;

* Institutions: integration of FOURMI in the Cameroon decentralization process;

* Participation: Strengthening of public involvement.

6. LESSONS LEARNED

The Nylon Upgrading Project

The project actors agree that any assessment of results must make allowances for the fact that the project was not just complex but also a long-term undertaking, designed and initiated at a time of powerful economic growth, continued during the recession, and completed at a time of economic, social, and political crises.

No global evaluation was conducted by the three funding institutions (World Bank, The Swiss Development Corporation and the Government of Cameroon) since each one had its own differing views. For the WB, the Nylon project has demonstrated the difficulty involved in adopting a broad policy approach with ambitious policy and institutional objectives and a large scope of project activities16.

The achievements of the First Urban project were mixed: the Nylon zone was significantly upgraded, but the application of high infrastructure standards led to the resettlement of more than 30 percent of the population, mostly lower-income families. Originally designed as a modest effort to provide the area's population with basic water and sanitation to be sustained through local financing, the project turned out to be a major urban intervention that involved the construction of primary infrastructure (a central market stall and primary transit roads) and required ongoing external funding. The WB considered the project largely unsatisfactory; with limited or poor results with respect to both physical and institutional aspects; thus the loan was canceled. The Bank's decision to lend to the urban sector of Cameroon again was on the condition that pending issues be resolved, such as compensation for displaced families and a careful auditing of the project.

The SDC, after playing an active part in designing and then implementing the Nylon project, decided to curtail its support in 1996 and to carry out a final assessment, so as to identify lessons for mounting subsequent urban projects. At the time of the evaluation the project was already over. The ARAN agency responsible for operations was disbanded. Any remaining activities had gradually returned to existing governmental institutions.

The final evaluation17 carried out in 1996 claimed that it was difficult to provide a scientific or statistically representative picture of the views of various players and of the population. It summarizes the principal findings in the following three points.

The project succeeded in:

* proper implementation of community facilities funded by SDC and the proper integration of schools and health centers into the folds of the respective sectoral ministries;

* secondary effects that undoubtedly helped to integrate the neighborhood and created a dynamic for progress.

The project experienced partial success in:

* its efforts to promote contractors and small companies which had been severely jeopardized by the economic downturn.

The project failed in:

* construction of infrastructures; in line with mistaken standards, roads were never connected to the rest of the network, were not maintained and rapidly fell into poor repair, making them partly unusable six or seven years after their construction;

* resettlement and housing improvement, all of which was almost completely abandoned for lack of resources after 1988 including because of the bankruptcy of Crédit Foncier du Cameroon and the non-payment of government grants to ARAN;

* improvement of the institutional structures; this was almost non-existent, because the organization responsible for implementing the project (ARAN) had almost no contacts with Douala's legally appointed authorities. Also the project suffered a conflict between the ARAN, MINUH and MINFIN due to funds redirected to unrelated purposes.

* regularization of land failed because land titles were not given to the population.

This final SDC assessment of the Nylon project also suggested several conclusions to be considered during the organization of subsequent projects in order to avoid the problems that occurred.

* Urban projects are very sensitive to economic, social, and political conditions. As towns constantly have to cope with a lack of resources it is impossible to guarantee that a particular project will be implemented at the expense of all the other ones. Urban projects must be designed in a more flexible way, defining social objectives, deciding on a financial envelope, and setting up a steering organization that can periodically assess the situation and decide accordingly what it is most sensible to do with available resources.

* When preparing a project, allowances must be made for the uncertainty of all forecasts. It is advisable to refuse project definitions based on only one projection of growth and progress.

* Funding should be restricted to actions that will remain useful in the event that economic conditions evolve more slowly than planned.

* When the aim is to improve the living conditions of the poorest section of the population, it is absolutely essential to impose only minimal standards. If the target neighborhood is suddenly improved to a higher quality than other neighborhoods, it will be impossible to avoid land speculation, which will once again exclude the poorest.

* Major land speculation will occur, with land changing hands, encouraging rising incomes but quite incompatible with the poorest people staying in the area. Between the initial project ideas dating from later 1970s (minimum access to the neighborhood and improved conditions for the poorest people) and the final 1985 version (construction of an improved road network for the whole city) it was quite impossible to uphold the same social objectives.

FOURMI: the limits of micro-projects.

* Micro projects are too often designed as infrastructure building programs, and the physical aspects of micro-projects can take greater importance than the objective of developing the decision-making powers and management capabilities of the project beneficiaries;

* They focus on one partner at the local level and cannot reach the most disadvantaged groups;

* They can only help reinforce those basic local authorities that are well structured. In other cases, they have little impact on the organizational capacities at the municipal level. In a great many cases, participation from beneficiaries ends up being limited to some kind of "contribution," with insufficient attention given to decision-making and managing the projects;

* Intermediate non-governmental operators are often used, without any clearly defined policy. These operators are often considered to be subcontractors, whereas in fact they are and will most likely become full-fledged partners;

* The viability of micro-projects is rarely guaranteed, because of the lack of coherence with national and local planning.

7. CHALLENGES AND PROPOSED NEXT STEPS

1.19 Follow-up to FOURMI I

In addition to the issues relating to FOURMI I highlighted above, the EU has introduced three new directions:

1. A move away from micro-projects towards a decentralized cooperative approach.

From the results of the mid-program evaluation in 1997 and the feasibility study at the end of 1998, it can be seen that FOURMI has really been a program concerned with infrastructure creation and micro-projects. It was, however, also important that local authorities become "owners" of the program as an instrument for supporting decentralization and participation of local populations.

2. Elimination of the economic component

After over two years of mixed results, the EU decided to join with the Agence Française de Développement (AFD) to co-finance a new program designed specifically to finance very small businesses in urban areas.

3. Concentration on the two main cities in Cameroon: Yaoundé and Douala

To avoid overlap of the two programs, Programme d'Appui aux Capacités Décentralisées de Développement Urbain and FOURMI II, the EU decided to restrict the geographical coverage of the FOURMI program to the cities of Yaoundé and Douala only.

1.20 Planning Activities for FOURMI II

The EU has presented recommendations for the implementation of the new FOURMI II:

1. Planning component: Emphasis on the neighborhood dimension

In essence, it is important to recognize the "neighborhood " at the urban level and at the social level (knowledge of actors, monographs, strategic analyses etc.).

2. Participation component: Change from a logic of projects to one of actors

Strict adherence to technical aspects of micro-projects is not sufficient to meet the objective of reinforcing basic capacities. If future projects aim for more systematic partnerships with intermediate NGO operators, a new dimension must be included: strengthening these NGOs. Moreover, the program must actively contribute to the building up of its NGO partners, since a transfer to local Cameroonian actors must be an integral objective of this second phase of the FOURMI II.

3. Institutional component: Involvement of the municipalities

Thus far, FOURMI has worked exclusively through NGOs, to the detriment of the involvement of other actors, especially municipalities and technical departments available in the urban communities. In FOURMI II, however, the aim is to achieve more systematic relations with municipal councils through a few specific projects, promoting their involvement in the program so as to obtain cooperation between actors in the neighborhoods and in the municipalities.

4. Investment component: Creation of a support fund for urban micro-projects

Funding for new projects benefiting the general public will be financed up to CFAF 20 million (US$40,000) with the aim of improving living conditions of local populations.

Given these limits, which have also been applicable to FOURMI I, the aim is to make the FOURMI II a genuine decentralized cooperative program. This approach is characterized in particular by:

(i) Support for giving control of local development projects to decentralized actors rather than simply support for creating physical structures,

(ii) Promoting participation rather than simply a financial or physical contribution (which is still demanded) so that all actors are involved in the development process,

(iii) Projects with more autonomous and decentralized management, in particular at the project design stage of component selection.

Annex A: Country and City Profiles

Annex B: Bibliography

Arnoud, M. Contribution a une Revue du Secteur Urbain au Cameroun. Nov.1994.World Bank.

Bolay, Jean-Claude. Rapport de Fin de Mission D'expert de la Cooperation Suisse Dans le Cadre du Projet de Restructuration et D'amenagment de la Zone Nylon. 1989.

Douala, M. Bell Schaub Rapport Final D'activites Doual'art dans le Programme FOURMI. 1998NYLON. Evaluation-URBAPLAN. Novembre 1988.

First Urban Project. Project Performance Audit Report. June 1990.

GRET. Développement participatif urbain au Cameroun- Le programme Fourmi. 1998.

GRET-A.F.V.P. Aménagement locaux dans le quartier Nkonldongo à Yaonundé 4.

Mbassi, Pierre Elong. L'habitat et L'amenagement Urbain-Institut Africain de Gestion Urbaine. 1991.

Sanz Corella, Beatriz. Orientations pour le Programme de développement participatif urbain. FOURMI II-UE.

Sanz Corella, Beatriz. Programme de Developpement Participatif Urbain- FOURMI II. Cooperation Decentralisee Villes de Douala et Yaounde. 8ème Fed-Termes de Reference. UE. Juin 2000.

Second Urban Project. Staff Appraisal Report. March 1996.

Second Urban Project. Staff Appraisal Report. October 1988.

Secrétariat d'Etat à la Coopération. Les projets de quartiers. Collection Evaluation No 32. 1997.

Tesh, Suzanne Snell. Republic of Cameroon, Second Urban Project. Resettlement Review. 1993

Urban Development Project. Staff Appraisal Report. February, 1983.

Urbaplan. "Project Nylon Cameroun." Evaluation finale et capitalisation de l'experience. Novembre 1996.

Annex C: Contact Information

| Name |

Organization |

Position |

Address/Telephone

E-mail |

| YANGO Jean |

Douala City |

Director Technical Services (DST) |

JeanYango@Yahoo.Fr

(237-42-3435) |

| DNOUMBE Marcelin |

MAETUR |

Regional Representative Douala |

Mclin.ndumbe@Iccnet.com

(237-37 66 00) |

| ETONDE EKOTO Edouard |

Communauté Urbaine de Douala |

-Governement Delegate

-Council President

|

(237) 42-6950 |

| MANDENG Gaétan |

Communauté Urbaine de Douala |

Deputy Director Technical Services |

Mandeng_g@yahoo.fr |

| BOUMY Mary |

ADL |

Representative Director |

Espace Metier |

| HENNART Christophe |

GRET |

Representative |

Hennart.gret@camnet.cm |

| DOUALA-BELL Marilyn |

DOUALART |

Director |

doualart@benoue.camnet.cm |

| DIKONGUÉ |

Ministry of the Town |

Delegate |

(237) 44-39 89 |

| GIRNY Claude |

Yaoudé City/French Cooperation |

Technical Assistant |

girny@camnet.cm |

| AMIRAULT Philippe |

A.F.V.P. |

Regional Delegate |

afvp@iccnet.cm |

| BOLAY Jean Claude |

DDA |

Expert |

jean-claude.bolay@epfl.ch |

| Sanz Corrella Beatriz |

European Union |

Project Manager |

Beatriz.sanz@delcmr.cec.eu.int |

Annex D: Photographs

NYLON NEIGHBORHOOD

|