|

|

Learning & Memory: Research

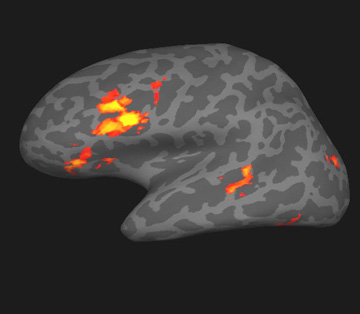

The ability to remember the past is critical for many levels of human behavior, from day-to-day behaviors, such as remembering to take medications, to more fundamental cognitive abilities, such as the development and use of language. Broadly, the objectives of the research in the Wagner lab are to understand how human memory is organized and supported by the mind and brain. A particular emphasis is placed on understanding the interaction between cognitive control and long-term memory, as well as on delineating the nature of "cross-talk" between different forms of memory (e.g., interactions between explicit/declarative and implicit/nondeclarative processes). In the course of these efforts, we further aim to characterize the functional contributions of specific prefrontal and medial-temporal regions to learning and remembering. Cognitive Control and Episodic Memory Our research program advances the perspective that PFC-mediated control mechanisms are not restricted to stimulus processing and working memory functions. Rather, we emphasize how long-term memory formation and retrieval depend on the "control of memory." In particular, we aim to identify and characterize the nature of the attentional control processes that contribute to the building or acquisition of memories and that guide the retrieval of existing memories. In these efforts, we focus on the interplay between PFC-mediated mnemonic control processes, long-term representations that are stored in posterior neocortical association areas, and binding mechanisms subserved by the medial-temporal lobe (MTL). Our efforts to understand mnemonic control have included attempts to delineate the cognitive and neural mechanisms supporting (a) controlled retrieval from semantic memory, (b) episodic memory formation, and (c) episodic retrieval with and without recollection. Controlled semantic retrieval. Recovering meaning about the world in a context-relevant manner is critical to cognition. It allows us to flexibly access information about concepts and objects in order to comprehend inputs and generate responses. Although on a continuum, there are two basic routes to retrieving relevant knowledge from semantic memory: automatic and controlled access. Over the past five years, our research has explored the mechanisms that support controlled semantic retrieval and that accompany the transition from controlled to automatic access. Initial results suggest that controlled semantic access partially depends on computations supported by a subregion in the left PFC (e.g., Wagner, Desmond et al., 1997; Wagner, Koutstaal et al., 2000; Wagner, Pare-Blagoev et al., 2001; Wagner, 2002; Badre & Wagner, 2002). These computations are recruited when the strength of association between the retrieval cue and target knowledge is particularly weak or when task-irrelevant competing knowledge is present (Wagner, Pare-Blagoev et al., 2001; Badre et al., in prep). Thus, we posit that a top-down bias signal that guides the recovery of meaning is recruited under situations in which target knowledge is not retrieved through more automatic routes, either due to weak stimulus-stimulus associations or due to interference from competitors (thus requiring selection). We are currently exploring how cognitive aging affects this controlled retrieval process; our initial results suggest that aging results in a breakdown in PFC gating of MTL retrieval processes, thus rendering the elderly more susceptible to pre-potent but irrelevant associations. Episodic encoding. In the course of a typical day, humans experience many complex events, such as perceiving scenes and objects, reading words and text passages, and interpreting spoken phrases. Yet, at the end of the day, only some experiences are memorable, with many of the day's events having been forgotten. Central to understanding memory is determining why some experiences can be later remembered, whereas others are forgotten. One factor that influences subsequent memorability is the nature of the executive control operations engaged during episodic encoding -- the process of transforming an experience into a durable memory trace such that it can be subsequently consciously remembered. PFC control mechanisms, in addition to influencing stimulus processing, may guide episodic memory formation by bringing task-relevant representations on-line and thus rendering them available for input into the medial-temporal lobe (MTL) memory system. Our efforts to specify the underpinnings of episodic learning have revealed a set of findings that bear on cognitive neuroanatomic theories of memory. Our fMRI data suggest that distinct regions in left and right PFC impact memory formation depending on the content of the to-be-learned experience, with the extent of recruitment of PFC control processes during an experience being predictive of whether that experience will be later remembered or forgotten. For example, our results implicate left inferior PFC and left MTL structures in the encoding of stimuli that have associated semantic and lexical representations, and right inferior PFC and bilateral MTL in the encoding of visuo-spatial codes (Wagner, Poldrack et al., 1998; Wagner, Schacter et al., 1998; Kirchhoff, Wagner et al., 2000; Davachi, Maril, & Wagner, 2001; Clark & Wagner, 2003; for a review see Paller & Wagner, 2002; Wagner, Koutstaal, & Schacter, 1999). This content-sensitive pattern of PFC activation has been interpreted as reflecting the recruitment of frontally-mediated control processes that allocate attention to semantic, phonological, and visuo-spatial representations, thus guiding their input into long-term memory (Wagner, 1999; 2002). More recently, we have begun to explore whether different forms of declarative memory (e.g., recollective vs. familiarity-based memory) emerge from separable MTL learning mechanisms. A central debate currently receiving considerable attention in the field is whether recollection and familiarity reflect quantitative or qualitative differences in the nature of the underlying memory representation, and, if the latter, whether these two forms of remembering depend on separable components of the MTL memory system. From a dual-process perspective, it has been hypothesized that the recollection of specific episodic details and the subjective sense of stimulus familiarity are qualitatively distinct and neurally separable. Neurally, it has been suggested that recollection specifically depends on hippocampal auto-associative processes that support later pattern completion by encoding the relation between event features, whereas familiarity may reflect a global match between a retrieval probe and perirhinal representations of the "gist" of past experiences. Our initial efforts indicate that the hippocampus is particularly associated with relational encoding, predicting later memory when encoding entails that allocation of attention to the relation between items in an event, relative to when attention is simply allocated to the items themselves (Davachi & Wagner, 2002). Moreover, we have observed that activation in the hippocampus and perirhinal cortex during an experience is correlated with different aspects of later memory for the experience. Activation in the hippocampus does not differentiate between events later remembered and those later forgotten, but rather differentiates between those subsequently remembered events that were accompanied by recollection relative to those not accompanied by recollection. By contrast, perirhinal activation predicted later item recognition and was uncorrelated with later recollection (Davachi, Mitchell, & Wagner, in press). These findings are the first, to our knowledge, that demonstrate that the subregions within the MTL circuit support different forms of episodic learning. Episodic retrieval. The contributions of cognitive control to episodic memory are not restricted to the building of memories. Rather, the research that we've conducted over the past few years implicates PFC-mediated control processes in the retrieval of distinct aspects of a past episode. For example, our initial results revealed that right frontopolar cortices appear to support the evaluation of the products of an episodic retrieval search, with the engagement of these monitoring processes being strategically recruited depending on their perceived utility (Wagner, Desmond et al., 1998; for discussion see, Wagner, 1999). In a subsequent line of work, we have further identified and characterized separable PFC substrates that are recruited depending on whether a retrieval decision requires the recollection of contextual details or an assessment of non-contextual stimulus familiarity. In one study (Dobbins, Rice, Wagner, & Schacter, 2003), our results revealed distinct lateral PFC and parietal structures that distinguished attempted source recollection from judgments of relative stimulus familiarity, with these effects of retrieval orientation being independent of retrieval outcome. Source recollection relied on left PFC-mediated monitoring operations, whereas familiarity-based remembering recruited similar right PFC computations as those observed in our prior study of the strategic monitoring of memory products (Wagner, Desmond et al., 1998). In a subsequent experiment (Dobbins, Foley, Schacter, & Wagner, 2002), we sought to further specify the nature of the control processes that are recruited during recollection (operationalized as source retrieval). Cognitive theory suggests that source retrieval requires cue-specification and monitoring processes not required during familiarity-based remembering. In this follow-up, we isolated multiple, distinct response patterns in left PFC related to semantic analysis/cue specification (anterior ventrolateral PFC), recollective monitoring (posterior dorsolateral and frontopolar PFC), and maintenance/rehearsal (posterior ventrolateral PFC). Importantly, cue specification and recollective monitoring processes were not engaged during simple familiarity-based memory, and were not products of episodic retrieval success. These results are beginning to provide evidence that attempted recollection of episodic detail requires multiple, neurally distinct forms of cognitive control.

Interactions between Forms of Memory Although implicit memory may not support explicit recognition judgments, we have been examining whether implicit memory may negatively impact episodic encoding. This hypothesis stems from the synthesis of three recent findings. First, as considered above, the magnitude of neural activity in left prefrontal regions during the encoding of words has been shown to predict whether or not those words will be subsequently remembered or forgotten (e.g., Wagner, Schacter et al., 1998; Kirchhoff, Wagner et al., 2000; Davachi, Maril, & Wagner, 2001; Clark & Wagner, 2003; for reviews see Wagner, Koutstaal, & Schacter, 1999; Paller & Wagner, 2002). Second, prior processing of a word results in decreased activation in these same left PFC regions during subsequent processing of the word (e.g., Wagner, Desmond et al., 1997; Wagner, Koutstaal et al., 2000; Kirchhoff, Wagner et al., 2000). Finally, behavioral and neuroimaging studies of amnesic patients indicate that this repetition-induced decrease in left prefrontal activation reflects the operation of implicit memory processes (i.e., priming). Taken together, these separate lines of results suggest that priming may impair episodic encoding, perhaps by resulting in decreased encoding variability. To explore this possibility, we conducted a fMRI study of the spacing effect (Wagner, Maril, & Schacter, 2000) -- that is, the observation that episodic memory is superior following greater temporal spacing of practice trials relative to when practice trials appear closer together in time. Our results revealed that the shorter the interval between initial and repeated processing, the greater the behavioral and neural priming effects. Moreover, the greater the priming effect during repeated processing, the less likely the person would remember the stimulus when probed by a later recognition memory test. In addition, when the temporal lag between study trials was held constant, a similar negative correlation between priming and episodic encoding was observed across subjects. We are presently directly testing our hypothesis that priming hinders episodic encoding primarily because it reduces encoding variability. Beyond explicit-implicit interactions, our focus on the role of cognitive control and episodic encoding also emphasizes the relation between working memory and episodic learning. The cognitive behavioral literature has been interpreted as indicating that the extent to which a stimulus is rehearsed or maintained in working memory is unrelated to whether the stimulus will be later remembered or forgotten. However, building on initial behavioral evidence that rote rehearsal may impact later recognition memory, our lab has recently demonstrated neural evidence for a link between working memory maintenance and episodic encoding (Davachi, Maril, & Wagner, 2001). Specifically, we observed that when rote rehearsal of words is accompanied by a greater magnitude of activation in prefrontal, parietal, cerebellar, and supplementary motor regions associated with verbal working memory, there is an increased probability of being able to later recognize the rehearsed words. Moreover, Baddeley and colleagues (1998) have hypothesis that this verbal working memory system supports language acquisition by contributing to the building of novel phonological representations. Extending our working memory/episodic encoding study, we recently assessed whether the relation between activation in the frontally-mediated articulatory control component of verbal working memory and later memory is greater for orthographic inputs that lack pre-existing associated phonological representations. Our results revealed that when the stimulus is novel (e.g., pseudo-English words), relative to familiar (e.g., English words), the frontal control process that assembles on-line phonological codes appears to play a differentially greater role in the formation of episodic memories for the resultant codes (Clark & Wagner, 2003). In future work, we aim to further specify how working memory processes contribute to long-term learning.

New Directions: Multi-Modal Brain Imaging

|