REVEALING

URBAN WATERS

INTRODUCTION

Many streams once flowed across West Philadelphia.

The largest of these is Mill Creek, a stream that drains nearly two-thirds

of West Philadelphia. Its headwaters are outside the city in Lower Merion,

and it flows into the Schuylkill River south of Woodland Avenue near 43rd

Street. The Mill Creek cut a deep valley across parts of West Philadelphia

and meandered and pooled in other areas. The large, grassy bowl in Clark

Park was once a mill pond. In the late 1800s, Mill Creek was buried in city

sewers. Its streambed was filled in and roads and houses were built on top,

but it still flows beneath city streets. The steep valley is clearly visible

in places like 47th to 48th Streets between Fairmount and Aspen and along

43rd Street from Walnut to Spruce Streets. Mill Creek now carries the rain

that falls on much of West Philadelphia as well as sewage from thousands

of private homes and businesses. Yet to most people the Mill Creek is invisible.

Though Mill Creek is buried in a sewer, it continues to shape landscape

and life. How can the buried river be revealed and rainwater celebrated

so people feel and know the importance of these urban waters?

PANTA

REI

"Panta Rei", that is "everything flows",

is the phrase which synthesize the belief of Eraclitus from Efeso, a greek

philosopher (lived in the first century b. C.) who has metaphorically identified

water with life. According to his thought, a flowing river shapes the continuous

becoming and transforming of life. As an emblem of birth and growth, water

is among the four substances, the one which deserves to be celebrated the

most. Moreover celebration implies man's participation, which must be recognizable

on the basis of a design. At this point I am going to think about a more

specific and realistic matter concerning Mill Creek: the buried river. Three

are the hypothesis which spring to mind.

|

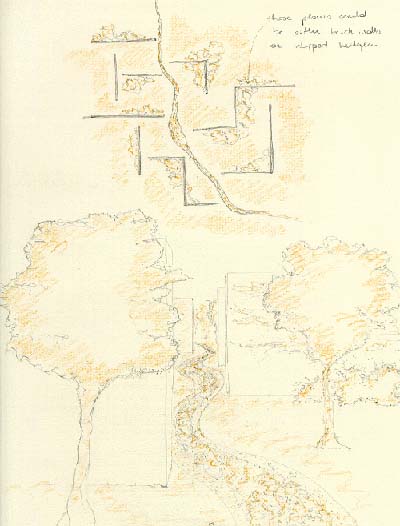

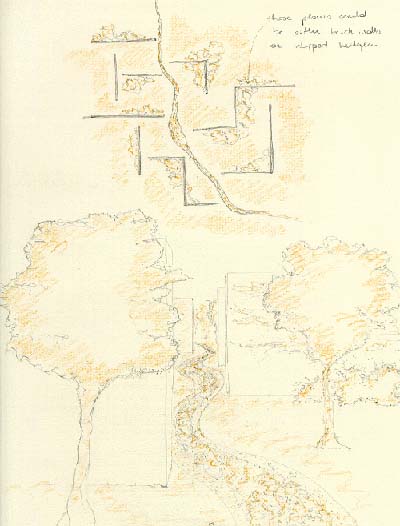

First of all leaving the stream where it is, underground,

and improving the system of drains; in this case just the absence of water

would be celebrated and the valley could be covered with a series of gardens

in which geometry emphasize the importance of man thought. In order to reach

the main purpose, the memory of water should be felt in each of these gardens:

there would be cascades of flowers, green pools and pebbles disposed as

they were a liquid surface. I proceed with a series of abstractions concerning

Philadelphia's urban design, whose development has ignored the presence

of the rivers. |

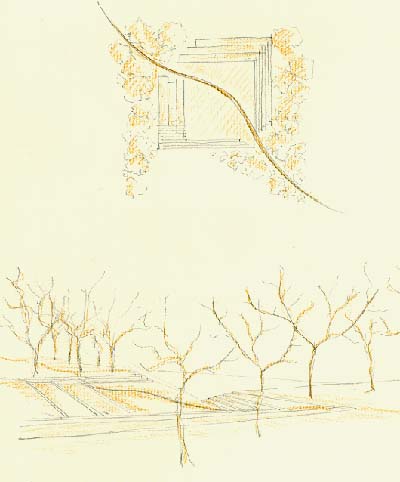

According to the second hypothesis the stream could be

separated from the sewers and brought up to the surface. In this way water

becomes a tangible and bursting presence. The idea would be that of a fluvial

park: thick vegetation flanking the river.

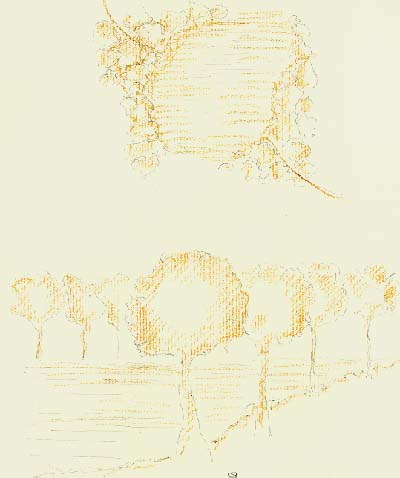

The third suggestion could be a synthesis of the first

two. Mill Creek could flow either on the surface or underneath it. Underground

water would be characterized by its constant speed , while on the surface

it would rest and fill some kinds of pond in strategic plots. In this case

there would be two different moments interpreted by two different "architectures".

I will suppose that water flows on an artificial streambed clearly designed

by men: when it is dried , it resembles a mineral landscape where order

dominates; when it rains, and the sewer will not support the rate of flow,

water expands into designed beds so turning the environment into an informal

and organic landscape. In this way, the landscape would be characterized

by a changeable quality and it would never be monotonous: therefore celebration

of water and life would take place. |

|

|

|