Below is a high-altitude infrared photograph of the Boston metropolitan area. The image was taken by NASA in 1980. In this map, one can see (without the interruption of street names or drawn-in boundaries) the entire area. One can see the topography, the open space, the ruggedness of the land.

“The blue color indicates the area of urbanization: buildings, streets, parking lots and other paved areas. Foliage and earth reflects infrared radiation and therefore the red indicates the open and natural areas of the region.” (Source: Krieger, Mapping Boston)

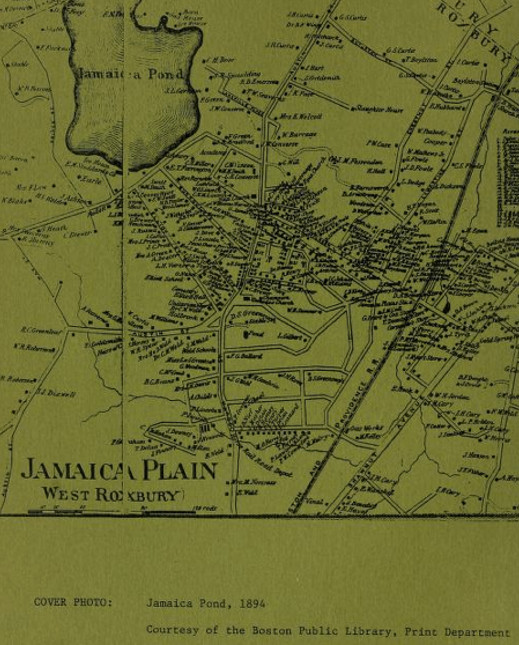

And in addition to all that, one can see clearly what’s vegetation and what isn’t, what reflects infrared light and what doesn’t, and one can see that while urban areas are distinct in their verdigris in this map, they are not homogenous. There are patches of “nature” scattered throughout the city, just as there are nonreflective patches of “urbanization” outside of it. Look southeast of Boston. Of the two large ponds just south of the Charles, the westernmost is Jamaica Pond. My site lies on the eastern shore. It’s a short, straight street that leads to the Pond: Pond Street.

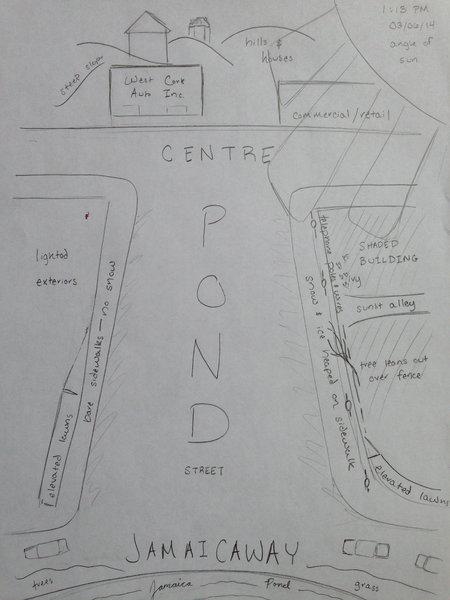

Pond Street is the link between Centre Street and Jamaicaway, between the busy, mixed-up townscape and wide, flat surface of Jamaica Pond. This swatch of land, no more than a fourth of a mile in width or length, is a transition zone. It is a mosaic of gentle gradients and sharp boundaries. Marked by edges—the shore of the pond, the edges of shadows, brightly lit faces of buildings, barriers of ice between the sidewalk and the street—it nonetheless illustrates the concept of flow, as discussed in Anne Whiston Spirn’s Granite Garden. Air, light, water, and people flow continuously through the environment, directed not only by street maps, but also by the physical laws of the ecosystem. Natural processes guide urban development. In addition to guiding construction, placing constraints, and determining a variety of human and infrastructure needs, natural processes shape our interaction with the environments we build.

The walk from Stony Brook Station to Jamaica Pond is hilly. Houses loom from elevated lawns, and low walls of stone delineate some sidewalks. In the early afternoon, the street is a patchwork of sun and shade. East of Centre Street, before Pond Street, the absence of landmarks and open spaces makes it hard to tell north from south. The rocky, undulating terrain impairs visibility; houses jut upward like tiny mountains all around.

The walk from there is downhill. Nearing my site, the stretch of Pond Street between Centre Street and Jamaicaway, the road flattens out. It slopes, straight and gentle, southeast to northwest, down to the edge of the frozen pond.

Source: Pollan, Kennedy, and Gordon.

An archived Jamaica Plain Preservation Study, prepared in June 1983, accompanies the map above with this statement: “Contrary to its name, Jamaica Plain is flat in only two areas: one bounded by Centre Street and the east side of Jamaica Pond and the other following roughly the Stony Brook Valley.”

Construction in Jamaica Plain, as is to be expected, followed the contours of the topography. The general topography here is relatively rugged: the length of Boylston I walked down to get to my site on my most recent visit was far hillier than the stretch of the same street I’ve biked to get there previously. Note that the first flat area described in the excerpt above has the exact same boundaries as my site. When I selected my site, I was not seeking out a region marked by a unique topography, but there was a different feel to the area. I attributed it to the houses, the pond, and the park, but there was something I didn’t put my finger on that set the site apart. It felt distinct from almost everything else I had seen of Jamaica Plain.

The largest houses, the colonial mansions closest to the pond, did have something in common with the homes in the hills: stone walls separated them from the sidewalk. The lawns of these houses were two to three feet above the sidewalk and the street. This was true of the houses further east (many of those walls were even higher: some houses had front doors with ten feet of elevation over their driveway entrances) but was not true of the apartment buildings and commercial spaces next to Centre Street. Starting at Centre Street, the disparity between lawn elevation and street elevation grew steadily from nothing to something worthy of a foot-thick fence of rocks. My instinct is to guess that these rocks were not brought in from far away. Jamaica Plain is a roughhewn landscape, and some leveling must have occurred during the growth and settlement of the neighborhood, perhaps around the time these mansions were built. The picture below, which I took facing east from Centre Street (my back was to the pond) shows an outcrop whose rubbly contents look similar to the material used in the foundations and borders pictured in my photographs:

Top: a rocky hill rises just behind a flat paved area. Middle, Bottom: Rocky materials used in construction of homes and fences.

When I visited around 1 PM a couple of days ago, the northern side of the street was bright. The front faces of the buildings were entirely lit, the sidewalks were nearly free of ice, and sunlight fell even into recessed doorways. The sun was not low in the sky, but it was falling toward the west, and the buildings on the south side of the street (which is angled so the its western end is further north than its eastern extremity) were fully shaded. The sidewalks in front of them were heaped with ice and snow, in contrast to the bare, illuminated concrete across the street. Walking down the southern sidewalk, I came to a break in the shade: an alley shone brightly, as a beam of sunlight struck parallel to it.

Across the street, a tree reached up to receive that sunlight, its branches carefully snaking around the wires of a telephone pole.

The quality of light (the angle of the sun is different now, in March, than a few months ago) reminded me that soon, these branches will have leaves again. This area, again, is marked by transition--not only spatially, but also chronologically.

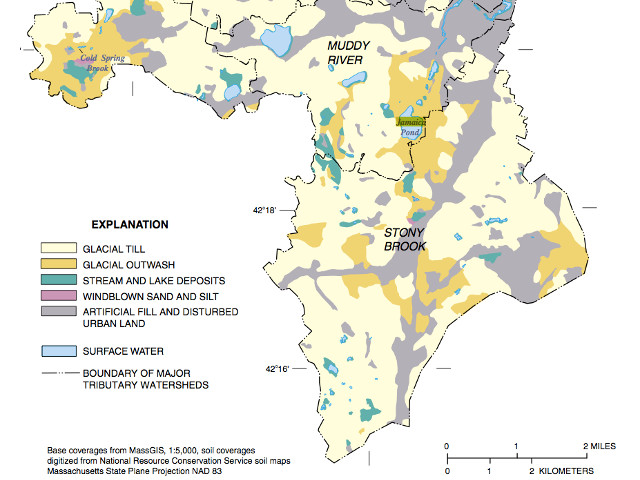

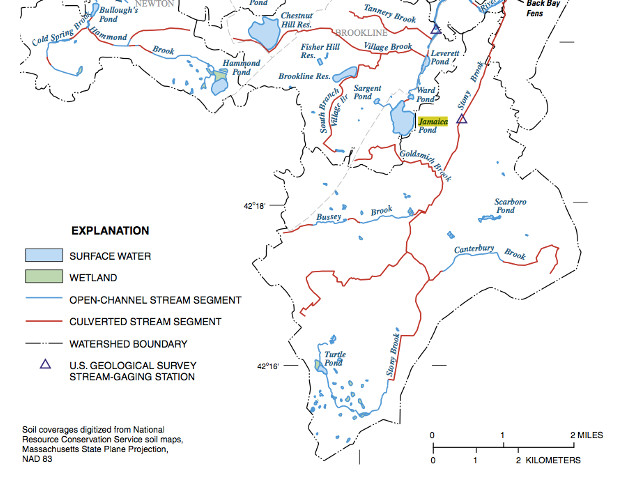

A plaque set into the sidewalk a few yards away, in the middle of my site, warned against dumping. The outline of a fish gave weight to the message: “Drains to Neponset River.” Outside the boundaries of my site, but a mere few blocks away, another plaque said the same things, but with “drains to Boston Harbor,” and also nearby, yet another indicated that water dumped there would drain to the Charles River. These three divergent drainage paths, all so close to one another, suggested to me the convergence of several watershed areas. I had not heard of Neponset River; I knew there was or had been a Stony Brook somewhere, only because the T station was named after it; and I had seen another smaller, pond connected to Jamaica Pond. These two maps, from the United States Geographic Survey investigation “Water Resources and the Urban Environment, Lower Charles River Watershed, Massachusetts, 1630-2005,” showed me more. I learned that Jamaica Pond is the source of the Muddy River, whose watershed includes most of Brookline, and that a stream connecting Jamaica Pond to Ward Pond runs hidden underground, through a culvert. As in The Granite Garden, “Covered and forgotten, old streams still flow through the city buried beneath the ground in large pipes, primary channels of a subterranean storm system” (Spirn).

Source: Weiskel, P.K., Barlow, L.K., Smieszek, T.W., 2005, Water resources and the urban environment, lower Charles River watershed, Massachusetts, 1630–2005: U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1280

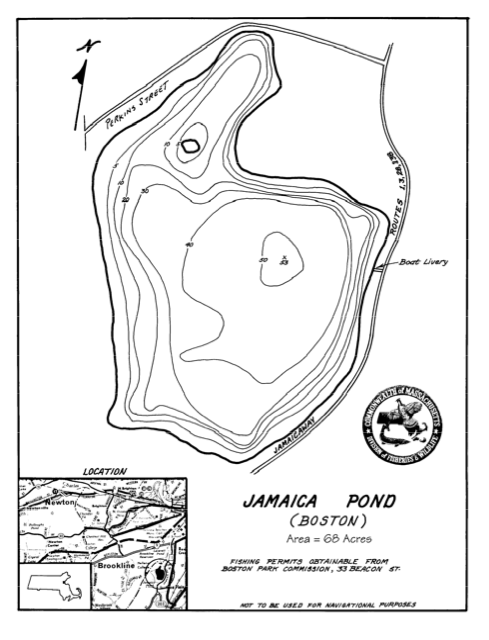

Jamaica Pond is the focal point of this neighborhood. The pond’s shape has not been altered much since its formation as a glacial kettle pond (Wieskel, Barlow, and Smieszek, 2005). Jamaica Pond is pictured even in early maps of the area, before there was much settlement to speak of. The boat house at the water’s edge hosts a neat row of white, upturned hulls. The surface of the pond, this time of year, is also white. It is frozen solid from shore to shore--to my (albeit untrained) eye, the layer of ice looks several feet deep. MA Fish Finder (a site dedicated to fishing spots in this region—“Get hooked on Massachusetts,” the header urges) says the pond has 68 acres of surface area. The maximum depth is 53 feet; the average depth is 25 feet. The bathymetry map below shows the contours of the bed of the pond.

Source: MA Fish Finder

My understanding of limnology is not much more enlightened than the profundal zone (the cold, dark part of a lake, unreached by the sunlight that illuminates the upper zones), but I understand the basic freezing process. In a Massachusetts winter, water freezes, and the ice, which is less dense than water, stays at the surface. I don’t know what the results are for the fish in Jamaica Pond: Fish Finder tells me the pond is generously stocked with trout, and a fisheries survey conducted in 1980 indicated that “the pond contained brook trout, rainbow trout, largemouth bass, chain pickerel, yellow perch, pumpkinseed and bluegill.” (MA Fish Finder). The occasional catch of an especially large brown trout, Fish Finder says, is evidence that there is some carry over from year to year—not all the fish die in winter.

“Nature is a continuum,” writes Anne Whiston Spirn in the prologue to The Granite Garden, “with wilderness at one pole and the city in the other. The same natural processes operate in the wilderness and in the city… The city is neither wholly natural nor wholly contrived.” This pond, artificially stocked with fish for the purpose of human recreation, encircled by a ring of pavement for joggers and pedestrians, is neither wholly natural nor wholly contrived. It is a habitat and an ecosystem. It is the focal point of the area, a recognized gem in the Emerald Necklace, the reason Jamaicaway curves and Pond Street points straight. The same natural processes take place in this pond as in a pond far away from here, sparkling somewhere in the wilderness, unpaved and undisturbed, but they occur differently, at different scales, in different ways.

Here, geese peck at the ground near benches, and they sip melting water from puddles between asphalt and bare wintry earth.

This one wears a plastic collar: a bright yellow tube with what looks to be the word ‘some’ is stuck around his or her neck. I watched for ten minutes as this bird, and its three companions, explored the ground for something to eat. They weren’t afraid of me. When I got close, this goose would pause, just like it is doing in the photograph, and look back at me, keeping its head still. I would pause, too, and after a few seconds, the geese would disregard me and go back to their own lives. They were used to people; they were gathered within twenty feet of the boat house, strolling down the path while college students and middle-aged women in athletic gear slogged past.

In The Granite Garden, “Rats, squirrels, starlings, pigeons, and house sparrows will probably always reside in the city, but a more diverse and abundant urban wildlife with the aesthetic and educational benefits it entails can be achieved with management.” (Spirn). I wonder what, if anything, people have done to keep this environment hospitable to creatures like these geese. Perhaps they feed the animals. Perhaps the nooks under the edge of the boathouse are warm in winter. The paving of the area around the pond has fragmented the ecosystem around the pond—I’d worry if these geese tried to cross Jamaicaway. “To many, observing the activities of wildlife, their foraging and eating, their mating and nest building, is an entrée to the mysteries of the natural world.” (Spirn). There was something captivating about this sight. I watched the small gaggle for a while longer, and before I headed back up the street, I looked over my shoulder to see where they were headed.

Humans crave connection with nature. When I came to Boston, I missed the oak savannahs, hills, valleys, and forests of fir I was used to in Oregon. The city seemed barren to me, like an abandoned playground. My eyes were untrained to the subtlety of nature in the city. “The natural environment of Boston,” Spirn writes, “Is no less ‘natural’ than the intensely cultivated landscape of the countryside or the shady streets and tended gardens of the outer suburbs.” Before, I might have drawn a sharp distinction between the “nature” of Jamaica Pond and the pavement of Pond Street and Jamaicaway. Now, I am able to see the gradual transition and the exchange between the two environments.

“However blind they may have been to natural processes, city dwellers have cherished isolated natural features and have sought to incorporate those features into their physical surroundings.” (Spirn). Jamaica Pond is an example of this, to some extent, but it is not isolated. It is part of the chain of parks designed by Frederick Law Olmsted to be “lungs of the city;” it is connected to the Fens, the Arboretum, and miles of grassy, watery parkland in between. Olmsted was not blind to natural processes. If he is guilty of anything, it is that he romanticized them. He saw nature as a panacea for the ills of city living. I can relate. After spending an hour on the T, a few minutes gazing out over the frozen pond feels restful. But we must be careful to remember that nature is not contained by the shoreline or the boundaries of the park. There is no sharp edge, like the shadows of the south side of the street, between natural and urban environments. In fact, even the edges of those shadows, which seem so definitive, are constantly changing. The lines shift with the angle of the sun, and if I looked closely, I’m sure I could find, in a few centimeters between the shade and the light, a microclimate functioning according to the same principles that govern the biosphere.

Works Cited

MA Fish Finder, 2013. Jamaica Pond Details. Retrieved from http://www.mafishfinder.com/jamaica-pond-24460-location.html on March 5, 2014.

Krieger, A., 1999. Mapping Boston. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Pollan, R., Kennedy, C., Gordon, E., June 1983. Jamaica Plain Preservation Study. The Boston Landmarks Collection.

Spirn, A.W., 1984. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic Books.

Weiskel, P.K., Barlow, L.K., Smieszek, T.W., 2005, Water resources and the urban environment, lower Charles River watershed, Massachusetts, 1630–2005: U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1280