“Two important characteristics of maps should be noticed. A map is not the territory it represents, but, if correct, it has a similar structure to the territory, which accounts for its usefulness.”

Alfred Korzybski, Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics

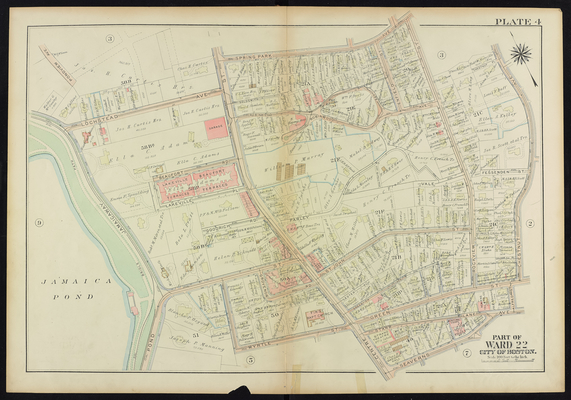

"Jamaica Plain, City of Boston, Ward 23, 1893." 1893. O.H. Bailey & Co.

My father used to distract me with lessons in semantics. Paraphrasing Alfred Korzybksi, he would remind me: “the map is not the territory; the word is not the thing.” A study of maps is not the study of a place, but is rather an examination of our relationship with the place. Maps are a sort of code: collected over time and revisited, they tell us what we once thought significant. Jamaica Plain has changed many times in the past hundred years. Its beginnings reflected change in the greater Boston area, in the style of city life, and in modes of transportation; its current state reflects a dynamic population, an ever-shifting social and political climate, and broader trends of urbanization. Maps can’t tell the whole story, but, like words invoke ideas and things, maps can help to paint a picture of the place.

Jamaica Plain, 1905. G.W. Bromley & Co., Jamaica Plain Historical Society.

Early maps of Jamaica Plain show orderly, spacious lots with large single-family residences. The mansions closer to the pond are bigger and fancier, with vast lawns and carriage turnarounds. I imagine this property was more desirable and more expensive, as waterfront property often is. The most noticeable differences between maps from the late nineteenth century and maps from the twentieth centuries are results of changing technology. The map below, from 1874, shows the Jamaica Pond Ice Company. Before the advent of fridges and freezers, ice was harvested from the frozen pond, stored in a warehouse, and distributed by wagon or, later on, by truck. Ice started out as a luxury good: only the wealthy had as much as they wanted of it. The mansions along the pond probably bought ice from the Jamaica Pond Ice Company, but simple convenience was what really made the pond’s edge the prime location for ice harvest and storage. After household electricity became commonplace, and refrigerators replaced old-fashioned iceboxes, businesses like the Jamaica Pond Ice Company became unnecessary.

Jamaica Plain, 1874. G.W. Bromley & Co., Jamaica Plain Historical Society.

Likewise, as streetcars and then automobiles became the prominent and preferred modes of transportation, carriage turnarounds fell into disuse, and eventually vanished. Compare the map immediately below, from 1899, which clearly shows looping and circular driveways on each major residential estate, with the next map (from 1965).

Jamaica Plain, 1899. G.W. Bromley & Co., Jamaica Plain Historical Society.

Boston, Massachusetts Sanborn Insurance Maps, 1965, Volume 7, Sheets 10, 19, 20 and 22.

Priorities change over generational time scales—technology changes, lifestyles change, values and needs and communities change. Between the turn of the century and the mid-1900s, significant changes occurred in Jamaica Plain. Before undertaking research on my site, I had a vague notion of Jamaica Plain’s history: I knew that it had begun as a wealthy streetcar suburb, had undergone a period of decline, mostly recovered, and entered a period of gentrification which it is still experiencing. Walking down Pond Street, I thought I saw evidence of this change over time. The white pondside mansions were clearly older than the triple-deckers and apartment in the middle of the stretch between Jamaicaway and Centre Street, which were clearly newer than the connected brick storefronts on Centre Street. The mansions were built first; the shops next, to service them; and in the decades that followed, the space between filled in. Then it filled in some more, and then, in some places, it emptied again.

G.W. Bromley and Co., Jamaica Plain 1924 Plate 004: Centre Street, Jamaicaway.

Contrast the map above, from 1924, with the maps to follow, from 1965 (Sanborn).

Boston, Massachusetts Sanborn Insurance Maps, 1965, Volume 7, Sheets 10, 19, 20 and 22.

The properties owned in 1924 by Blanche P. Osgood and Joseph P. Manning have merged and, in the 1965 maps, are labeled “Our Lady of the Way.” Where wealthy Bostonians once kept homes, there is a school for girls and a convent. An adjacent lot contains a playground and locker room. Most noticeable is the conversion of Helen P. Schmidt’s expansive property into a 44 units of housing for the elderly. There was a small rest home a few blocks away, on Burroughs Street; there were another two larger complexes of elderly housing a few blocks in the opposite direction. These persisted into the eighties, and may well be there today. Why such high demand for housing for the elderly, why here? And what is the importance of the aforementioned trend: private residences turned into public institutions? Does it reflect the need for such institutions in 1960s Jamaica Plain, the value of the land at that time, or the social and political spirit of the time? I heard recently that present-day Jamaica Plain has such an influx of residents that buildings that once served as public institutions are being converted to housing. If this reflects the neighborhood rising desirability, perhaps the opposite trend reflects its previous decline. I also notice, with no hypothesis in mind, that many of the names on mansions and houses in the 1924 map are women’s names. Frances, Louise, Emma, Ida, Ada, Mary, Harriet. This surprised me—my grandmother, whose very proper ancestors hail from the Boston area, (to my mother’s dismay) still receives her letters addressed to “Mrs. Steven Weinstein.” I would have expected most properties in 1924 to be labeled with the names of men. I am aware, from walking around Jamaica Plain and seeing flyers, that the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail winds through Jamaica Plan. If I knew more about Boston’s cultural history, and this area’s in particular, I might have a better guess at the reason behind this gap between my expectations and the reality of the time.

I notice, too, that many individual residential lots from the resizedJP-1924mapmap are combined into larger properties in the 1965 map. This manyindicate that they were vacated and then purchased and parceled together by real estate investors, regular homeowners, landlords or institutions. Perhaps they were bought for low prices during a period of disinvestment. In the 1965 map, buildings along the edge of an entire block on Centre Street (between Goodrich Road and Lakeville Place) have been torn down and replaced by a filling station and the blank pavement alongside it. A filling station would not have been needed forty years prior, and if it had, it might have been built somewhere else.

Sanborn fire insurance maps from the seventies and eighties show followed discrepancies from the fifties, but this period in American history was fraught with change. The map is not the territory, the word is not the thing. The physical shape of this particular neighborhood in Jamaica Plain was relatively static, but the area as a whole was not. The old mansions remained standing, the rest homes, schools, and churches remained, and Centre Street continued to offer retail goods and services to the through-traffic and surrounding residential area, but I’m sure there were differences between 1965 Jamaica Plain and 1981 Jamaica Plain. I’m sure that, over the in-between period, there were changes in the population and also in the types of shops and services.

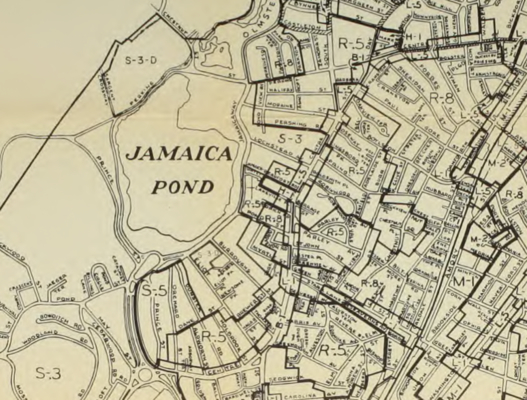

Zoning Districts, City of Boston, Jamaica Plain, 1962.

Jamaica Plain Neighborhood Zoning Map, 2014.

The zoning maps above describe land use in the area. The first map is from 1962; the second is from the present day. The maps are very similar. Pond Street and the short streets that run parallel to it or extend radially from the pond are characterized by residential use; Centre Street, especially to the south, is characterized by dense commercial use. The main change in the area, over the course of the twentieth century, was in residential density. Houses that listed one name in 1924 (and were likely single-family homes at that time) are later classified as two- or three-family homes. Apartment complexes and sprawling multi-family residences  replaced single-family homes with wide lawns and carriage turnarounds.

A man named Frank Norton, in an article on the Jamaica Plain Historical Society website, recalls growing up in 1950s Jamaica Plain. He remembers Centre Street, “where all the great shops were,” as the happening spot in town, a bustling stretch of commerce, and a site of employment for both teenagers and adults. In the article, published within the last ten years, he remarks upon the changes. “When we went back to visit our parents it wasn’t the same anymore,” he writes. “You could notice the differences taking place and the decline of the neighborhood.” The second half of the twentieth century was a time of widespread disinvestment in Jamaica Plain. “When my parents sold the 3 decker in the 1970’s,” says Norton, “you couldn’t give them away for $13,000. The insurance companies were redlining the neighborhoods and not selling fire insurance.”

The Sanborn fire insurance maps from the seventies and eighties are not marked with names or indicators of value. Such information, gathered over time, would paint a clear picture of redlining and decline in the neighborhood. But the maps are only outlines of disparate instants in Jamaica Plain’s history. They are static and incomplete. The map is not the territory, the word is not the thing: these maps have neat edges and uniform lines, but the triple-deckers and apartment buildings lining Pond Street and Centre bear marks of the passage of time. Styles of architecture, names on mailboxes, the ages and builds of cars parked in driveways, all betray bits of the neighborhood’s makeup and history.

The First Baptist church of the corner of Myrtle Street and Centre Street has been standing longer than one hundred years. It is there in every map I examined. Even its name contains an origin story. Today, the front of the church, facing Centre Street, boasts two enormous vertical banners. The one on the left reads “MANY CULTURES;” the one on the right reads “ONE FAITH.” Jamaica Plain today is a different place than it was a hundred years ago. Gone are the old-fashioned Anglican surnames on the mansions: names like Adams, Curtis, Greene and Seavern. Gone is the monotony of repetitive single-family blocks. The recent maps give no names—perhaps because properties change hands enough to render such details quickly obsolete; perhaps because it no longer matters the way it used to. Korzybski philosophized that a map, if correct, “has a similar structure to the territory [it depicts], which accounts for its usefulness.” These maps show only the physical structure of old Jamaica Plain. They are not intended to show the social, economic, and political structures within which humans navigate their lives. And yet, insofar as the physical environment, the mapped landscape, is shaped by these forces, we can see them.

Sources

“Boston, Massachusetts Sanborn Insurance Maps, 1965, Volume 7, Sheets 10, 19, 20 and 22.” Map. (Pelham: Sanborn Map Company, Inc., 1965).

“Boston, Massachusetts Sanborn Insurance Maps, 1974, Volume 7, Sheets 10, 19, 20 and 22.” Map. (Pelham: Sanborn Map Company, Inc., 1974).

“Boston, Massachusetts Sanborn Insurance Maps, 1981, Volume 7, Sheets 10, 19, 20 and 22.” Map. (Pelham: Sanborn Map Company, Inc., 1981).

G.W. Bromley and Co., “Atlas of the City of Boston, West Roxbury, 1924.” Jamaica Plain 1924 Plate 004: Centre Street, Jamaicaway. Retrieved from http://www.wardmaps.com/viewasset.php?aid=1321.

G.W. Bromley and Co. “1899 Bromley Map of Jamaica Plain. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/1899_Bromley_Map_of_Jamaica_Plain

"Jamaica Plain, City of Boston, Ward 23, 1893." 1893. O.H. Bailey & Co., Boston, Mass. Retrieved from

http://maps.bpl.org/id/10160.

“Jamaica Plain Neighborhood Zoning Map.” 2014. Boston Redevelopment Authority.

Norton, F. “Frank Norton’s 1940s and 1950s Jamaica Plain.” Jamaica Plain Historical Society. Retrieved from

http://www.jphs.org/20thcentury/frank-nortons-1940s-and-1950s-jamaica-plain.html

“Zoning districts, city of Boston, map 9, Jamaica Plain (1962).” Boston (Mass. Zoning Commission). Digitized by the Boston Public Library. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/zoningdistrictsc1962bost.