“The city’s flesh outspreads layer upon layer…”

Frank Lloyd Wright, “The Art and Craft of the Machine” in On Architecture: Selected Writings (1894-1940) (1941)

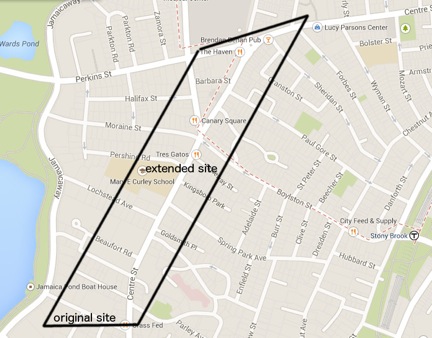

Jamaica Plain is a patchwork place, a vibrant collage of competing influences. The . Looking closely, peeling back the layers, picking at the seams of the neighborhood, we reveal its history. Along Centre Street, where the Pondside sub-neighborhood fades into Hyde Square, the seams—places where the layers of history and influence meet—are frequent and visible. For the purposes of this investigation, I am shifting my site slightly to the north, including the Pondside area that was the focus of my original inquiry, but extending my line of sight about nine blocks up Centre Street toward Hyde Square, and focusing only on the sides of the blocks that face Centre Street. I choose to do this because change can be more clearly demarcated along a line than over an area, and because Centre Street, as a main Boston thoroughfare, is important both historically and as a vessel for change, a route along which people, goods, and social movements progress. By slightly expanding the boundaries and focus of my site, I hope to capture the dynamism and vibrancy of Hyde Square, and examine the transitional area between the Pondside and Hyde Square sub-neighborhoods.

Google Maps. (2014).

Google Maps. (2014).

Jamaica Plain is characterized by ethnic and racial diversity, and Hyde Square in particular has numerous large immigrant communities. Bilingual signage is ubiquitous. Restaurants advertise “a taste of Cuba” and “Mexican and American Foods.” The concentration of small, independently-owned and run barber shops and salons along Centre Street in the Hyde Square region must be some kind of phenomenon: I’ve never seen anything like it. Every barber shop is packed, every time I pass. A number of storefronts advertise passport photos, cash transfers, and immigration documents all in the same window. Murals depict black and Latino youth, dancing, playing soccer, listening to music. Chronologically staggered influxes of immigrants have made the neighborhood the multilayered patchwork it is today.

A defining and continuous feature of Hyde Square and the surrounding area, over the past fifty years, has been community activism. There is a rich history of activism, and the tradition lives on, manifesting in new ways in the present day. Jamaica Plain residents united to stop the construction of I-95 through the neighborhood in the seventies. In the seventies, this was a neighborhood in decline: it was dangerous and deteriorating. Abandoned buildings quickly fell victim to arson, areas were redlined by insurance companies, and disinvestment was rampant. Old articles from the Jamaica Plain Citizen and the Boston Globe narrate a revolution. Neighborhood coalitions came together to fight redlining. Churches, neighborhood groups, and community organizers worked together to change the practices of banks and mortgage lenders, insisting on greater transparency in lending practices, and to stimulate residential investment in Jamaica Plain. Their success was so dramatic, Jamaica Plain began its swing to the opposite extreme: gentrification. The current state of Jamaica Plain is a result of this history. The photographs and anecdotes below tell the story. By discussing the context and significance of each image, I hope to provide a visual, historical map of Jamaica Plain’s Pondside and Hyde Square neighborhoods.

The church above is the First Baptist Church in Jamaica Plain. It resides at the corner of Centre Street and Myrtle Street, one block west of Pond Street. A plaque on display nearby says that the church has stood at this location since 1859. The name, “First Baptist Church,” indicates that this was the first institution of its kind in the area. Two vertical banners flank the door: in white block letters on a rainbow-colored background, they read “Many Cultures” and “One Faith.” I stood for a few minutes, on the Saturday afternoon I took this picture, and watched people come out of the church and head to their cars. There was an elderly white couple; there was a black father with two young children; there were old sedans and new station wagons and electric hybrids parked in the lot or idling, waiting for their drivers and passengers to finish church. Inclusivity, as advertised, was the dominant theme. I am sure this was not always so: in the 1874 and 1899 maps, this church was surrounded by large, single-family residences, labeled with names that reflected a homogenous population of wealthy, white Bostonians with Anglican origins. The church was built, originally, to serve that population. Over the years, it has changed to cater to a more diverse neighborhood. These banners, and the church’s slogan, are proof of the demographic change that has taken place in this area of Jamaica Plain over the past hundred years.

The photograph above shows a market on the west side of Centre Street, towards Hyde Square. It is one of many small grocery markets. Most have Spanish names; most stock an assortment of Caribbean, Latin American, and North American foods. They have colorful awnings and fliers in the doors and windows. On the Saturday I visited, most had at least a few customers. These, too, reflect the demographics of the neighborhood. Hyde Square is known as Boston’s Latin Quarter, “the heart of Latino life in Boston.” This title was posted on several signs in the neighborhood. In the late twentieth century, major influxes of Spanish-speaking people, mostly from the Dominican Republic, but also from Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Mexico, made Hyde Square a colorful melting pot of Latino culture. This, too, was evident in the signage. Murals and large-scale public art works are everywhere, on nearly every street corner or bare brick wall. Many seem recent; many appear to have been commissioned by or in honor of the mayor. Perhaps these murals reflect the ongoing efforts to “spruce up” the neighborhood; perhaps they merely reflect the aesthetics and the desires of the people who live there.

This is Mike’s Service Center at 626 Centre Street, right across from Pond Street. If you look closely, you can see the faded outline of the word “snacks” above the windows on the left side of the building. This auto shop was once more of a public attraction. Now, the nearby snack options (south of Pond Street, down Centre away from Hyde Square) are restaurants, boutique-y coffee shops, and a natural foods delicatessen. This area is rapidly changing. High-end stores and yoga studios nestle between the old shops. Here is Mike’s Service Center again, from a different angle.

In the background, I could see shoppers and afternoon lunch-goers making their way down Centre Street. It was a different crowd than the crowd in Hyde Square. Where markets in Hyde Square accepted food stamps for payment, cafés in the opposite direction advertised that customers who wished could pay via an iPhone app.

In Hyde Square, these worlds blend together. A bicycle repair shop called Revolution (in accordance with the zeitgeist of my generation) is flanked on either side by Quisqueyana and El Patio Market. Revolution is clearly newer than its neighbors. The Lucy Parsons Center, a recently relocated anarchist bookstore and community center, is surrounded by barber shops and salons. Hyde Square is home to a higher concentration of barber shops and salons than I’ve seen anywhere else. Some, like D’Friends Barber Shop and the High Style Hair Salon, have old-fashioned exteriors, with red and blue stripes twirling on poles by their doors. Some are modern, with new awnings and polished floors. Some, like Julio’s Barber Shop, are both: Julio’s boasts gleaming steel outdoor light fixtures and a navy blue awning emblazoned with chunky white sans-serif font. Below the awning are the traditional red and blue stripes and a sign in antiquated script.

Juxtapositions like these are the seams in the patchwork. Here, textures of change overlay remnants of the past.

The residences pictured above are both on Centre Street, less than a block away from one another (as you can tell by the house numbers). First we have a ‘404’ in a very traditional Bostonian style. Just around the corner of the same building, barely inches away, we have the house numbers on tiles, painted whimsically and decoratively in a fashion reminiscent of Mexican, Caribbean, or Hispanic art. And down the street, ‘396’ is hand-painted in large blue numerals underneath a blue cartoon character. Taken together, these three addresses aptly summarize all three major waves of settlement in Jamaica Plain’s history: first, the wealthy Bostonians; second, the Spanish-speaking immigrants; third, the current and ongoing influx of young, creative, not-quite-mainstream white twenty-somethings. Members of this third group, from a certain perspective, are the gentrifiers.

They are the reason there is now a Whole Foods on Centre Street. I stopped in Whole Foods to use the restroom during one of my expeditions to Jamaica Plain. I had just given ten dollars (the only bill I had on hand) to a homeless and nearly toothless man named Wallace by the Stony Brook T stop. Being hungry and cashless, I restricted myself to the free samples of fancy cheese and pre-popped caramel-coated popcorn. The Whole Foods was clearly new, or at least recently renovated. I was curious. It seemed out of place in this neighborhood. I asked a cashier how long the grocery store had been operating there. “Just a few years,” she answered.

“What was it before?” I asked.

Before the building was leased to Whole Foods, it housed a Hi-Lo. Hi-Lo stocked everything from Jarritos to bear oil to Cuban pastries, all at low prices. The closing of Hi-Lo, and its replacement by Whole Foods, was met with outrage in the community.

All down Centre Street, what used to be is mixed up with what is and what will be. The CVS below is no longer a CVS: it is a boutique yarn and fabric shop. Meanwhile, the billboard over its roof is tattered and blank.

This sign, on the door of a laundromat, is a whimsical illustration of change in the neighborhood. Ownership changes, old customers are displaced by new ones, people move, social environments change. An ornate door on an old institution has fallen into disuse and now bears a “no trespassing” sign. A proud and antique building looms behind an unpretentious clapboard home and a basketball hoop. The smell of cinnamon wafts onto the sidewalk from a pastelería. Conversation spills out of a barber shop as a handsome black man steps out, holding the hands of his two young children. Young women in yoga pants laugh on their way to lunch and lattes. The city’s flesh outspreads, layer upon layer.

All images by Natasha Balwit.

Sources:

Dolores Hayden, The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History (MIT Press, 1995)

Google Maps. (2014). [Hyde Square, Jamaica Plain, Boston, Massachusetts] [Street map}. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/maps/@42.3189274,-71.1097387,16z.

Jamaica Plain Historical Society. (2014). www.jphs.org.

Hyde Square Task Force. (2014). www.hydesquare.org.