It is impossible to represent to oneself empty space; all our efforts to imagine a pure space, from which the changing images of material objects would be excluded, can result only in a representation where vividly colored surfaces, for example, are replaced by lines of faint coloration, and we cannot go to the very end in this way without all vanishing and terminating in nothingness.

Thence comes the irreducible relativity of space.

Whoever speaks of absolute space uses a meaningless phrase. This is a truth long proclaimed by all who have reflected upon the matter, but which we are too often led to forget.

Photo: Maurice Terrien (courtesy of Yan Terrien)

I am at a definite point in Paris, the Place du Panthéon for instance, and I say, "I shall come back here to-morrow." If I am asked, "Do you mean you will return to the same point of space?" I shall be tempted to answer, "Yes"; and yet I shall be wrong.

Animation by Willow W.

I shall be wrong, since by to-morrow the earth will have journeyed hence carrying with it the Place du Panthéon, which will have traveled over more than 2 million kilometers. And if I tried to speak more precisely I should gain nothing, since our globe has run over these 2 million kilometers in its motion with relation to the sun, while the sun in its turn is displaced with reference to the Milky Way, while the Milky Way itself is doubtless in motion without our being able to perceive its velocity. So that we are completely ignorant, and always shall be, of how much the Place du Panthéon is displaced in a day.

In sum, I meant to say: "To-morrow I shall see again the dome and the pediment of the Pantheon, and if there were no Pantheon my phrase would be meaningless and space would vanish."

Photo: David Le Brun

This is one of the most commonplace forms of the principle of the relativity of space; but there is another, upon which Delbœuf has particularly insisted.

Animation by Beware IRCD

Suppose that in the night all the dimensions of the universe become a thousand times greater; the world will have remained similar to itself, (giving to the word similitude the same meaning as in Euclid, Book VI). Only what was a meter long will measure thenceforth a kilometer, what was a millimeter long will become a meter. The bed whereon I lie and my body itself will be enlarged in the same proportion. When I awake to-morrow morning, what sensation shall I feel in the presence of such an astounding transformation?

I shall perceive nothing at all. The most precise measurements will be incapable of revealing to me anything of this immense convulsion, since the measures I use will have varied precisely in the same proportion as the objects I seek to measure. In reality, this convulsion exists only for those who reason as if space were absolute. If I for a moment have reasoned as they do, it is in order the better to bring out that their way of seeing implies contradiction. In fact it would be better to say that space being relative, nothing at all has happened, which is why we have perceived nothing.

Have we the right, therefore, to say that we know the distance between two points ? No, since this distance could undergo enormous variations without our being able to perceive them, provided the other distances have varied in the same proportion. We have just seen that when I say, "I shall be here to-morrow," this does not mean that to-morrow I shall be at the same point of space where I am to-day, but rather that to-morrow I shall be at the same distance from the Panthéon as to-day. And we see that this statement is no longer sufficient and that I should say : "To-morrow and to-day my distance from the Panthéon will be equal to the same number of times the height of my body."

But this is not all. I have supposed the dimensions of the world to vary, but that at least the world would always remains similar to itself. We might go much further, and one of the most astonishing theories of modern physics furnishes us the occasion.

Delbœuf Illusion by Craig Aaen-Stockdale.

EDITOR'S NOTES:

From a physicist's point-of-view, the opening paragraphs of The Relativity of Space are notable mostly for defending the existence of scale invariance. The idea that the universe would look the same if everything were enlarged in the same proportion had already occurred to Galileo, who rejected it. (Mark Peterson has convincingly argued that the scale models whose failure originally disturbed Galileo were not of ships, as in the published account, but of the Nine Circles of Hell from Dante's Inferno!)

Poincaré does not mention Two New Sciences, but he does acknowledge a debt to the Belgian psychologist, hypnotist, and "psychophysicist" Joseph Delbœuf, with whom readers of Année psychologique would probably have been familiar. Remembered today mainly for discovering the optical illusion above, Delbœuf had hoped to be the Newton of psychology, but his level of mathematical knowledge was far below Poincaré's. Delbœuf's essay Megamicros discusses how the world might seem if the dimensions of the Sun and the Earth were half of their actual values. An English translation of Megamicros appeared in Popular Science 52, 678 (1898), under the title In a World Half as Large; it will be reproduced at Net Advance Retro next week, so we will not discuss it further here, except to point out one rather curious aspect.

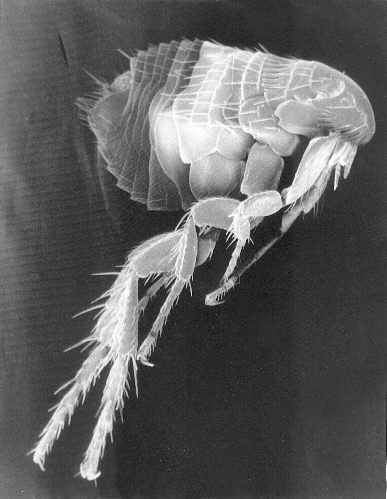

Both Galileo and Delbœuf placed great emphasis on the fact that scale models fail, because, for example, volume increases with the cube of the linear dimension. A uniform-density sphere of radius two centimeters weighs eight times as much as a sphere of radius one (assuming, of course, that the gravitational field is still the same). Therefore, as J. B. S. Haldane would famously point out in his 1928 essay On Being the Right Size, "for every type of animal there is an optimum size. Yet although Galileo demonstrated the contrary more than three hundred years ago, people still believe that if a flea were as large as a man it could jump a thousand feet into the air." Scale invariance, in this account, is not a symmetry of nature.

Image by Janice Carr, CDC

Poincaré simply rejects all this. He does not discuss why the person who wakes up in a scale-shifted universe would not at once notice being a different weight -- perhaps the constants of nature have also changed in some way? This seems remarkable, and it is certainly not an oversight. Poincaré uses the thought-experiment of a rescaled world in many of his writings. For example, in his essay "Les conceptions nouvelles de la matière" [Foi et Vie 15, 185 (1912); English translation by Melanie Frappier and Jeffrey Bub, Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 43, 223 (2012)], we read:

"Imagine a giant armed with an enormous telescope. He arrives from the depths of the dark abyss and is heading towards a sort of cloud that shines with a milky glare. It is our Milky Way ... [H]e asks himself, with many supporting arguments, if this cloud is made of continuous matter or if it is formed of atoms. Nevertheless he approaches and one fine day his telescope shows him myriads of luminous dots in this cloud. 'Ah! this time, this is it,' he says to himself, 'here they are, I've caught the atoms.' The poor soul does not know that these atoms are suns, that each of them is the center of a system of planets, that on each planet there are millions of beings who constantly discuss whether they are themselves composed of atoms."

Poincaré's insistence that the world is self-similar defies common sense, and yet it is one of his most profound contributions to science. At the very least, it anticipates the fractal analysis that will play such a role in Twenty-first Century physics. We will discuss conformal transformations in the notes to Delbœuf's essay; for now we need only observe that scale invariance plays a key role in what physicists usually mean by "relativity", to which Poincaré will next turn.

THE RELATIVITY OF SPACE, by Henri Poincaré