Palace of Charles V. Photo by "Hismatness" [Wikipedia].

Education

2014 May 26

SOURCE:

Einstein: Einblicke in seine Gedankenwelt --

Gemeinverständliche Betrachtegung über

die Relativitätstheorie und ein neues Weltsystem

entwickelt aus Gesprächen mit Einstein

von Alexander Moszkowski

[Hamburg: Hoffmann und Campe, 1921]

English translation:

Einstein the Searcher

translated by Henry L. Brose

[New York: E. P. Dutton, 1922], with a few additions and modifications.

Moszkowski's words are in bold.

School Curricula and Reform of Teaching. --- Value of Language Study.

--- Economy of Time. --- Practice in Manual Work. --- Picturesque Illustrations.

--- Art of Lecturing. --- Selection of Talents by Means of Examinations. ---

Women Students. --- Social Difficulties. --- Necessity as Instructress.

OUR conversation turned towards a series of pædagogic

questions, in which Einstein is deeply interested.

For he himself is actively engaged in teaching, and

never disguises the pleasure which he derives from imparting

instruction. Without doubt he has a gift of making his spoken

words react on wide circles anxious to be instructed, composed

not only of University students, but of many others quite outside

this category. When, recently, popular lectures on a large

scale were instituted, he was one of the first to offer his services

in this sound undertaking. He

lectured to people of the

working class, who could not be assumed to have any

preliminary information on the subject, and he succeeded in

presenting his lectures so that even the less trained minds could

easily follow his argument.

His attitude towards general questions of school education

is, of course, conditioned by his own personality and his own

work in the past. His first care is that a young person should

get an insight into the relationship underlying natural phenomena,

that is, that the curricula should be mapped out so that

a knowledge of facts is the predominating aim.

"My wish," Einstein declared to me, "is far removed from

the desire to eliminate altogether the fundamental features of

the old grammar schools, with their preference for Latin, by

making over-hasty reforms, but I am just as little inclined

to wax enthusiastic about the so-called humanistic schools.

Certain recollections of my own school life suffice to prevent

this, and still more, a certain presentiment of the educational

problems of the future ... To speak quite candidly," he

said, "in my opinion the educative value of languages is, in

general, much over-estimated."

I took the liberty of quoting a saying that is still regarded as

irrefutable by certain scholars. It was Charles V who said :

"Each additional acquired language represents an additional

personality" ; and to suggest the root of language formation he

said it in Latin : "Quod linguas quis callet, tot homines valet."

This saying has been handed down through the ages in German

in the form : "Soviel Sprachen, soviel Sinne" (An added

language means an added sense).

Einstein replied : "I doubt whether this aphorism is

generally valid, for I believe that it would at no time have

stood a real test. All experience contradicts it. Otherwise

we should be compelled to assign the highest positions among

intellectual beings to linguistic athletes like Mithridates,

Mezzofanti, and similar persons. The exact opposite, indeed,

may be proved, namely, that in the case of the strongest

personalities, and of those who have contributed most to

progress, the multiplicity of their senses in no wise depended on a

comprehensive knowledge of languages, but rather that they

avoided burdening their minds with things that made excessive

claims on their memories."

"Certainly," said I, "it may be admitted that this gives

rise to exaggeration in some cases, and that the linguistic sort

of sport practised by many a scholar degenerates to a mere

display of knowledge. An intellectual achievement of lasting

merit has very rarely or never been the result of a superabundance

of acquired linguistic knowledge. An instance

occurs to me at this moment. Nietzsche became a philosopher

of far-reaching influence only after he had passed the stage of

the philologist. As far as our present discussion is concerned,

the question is narrowed down considerably : it reduces itself

to inquiring whether we do sufficient, too little, or too much

Greek and Latin. I must remark at the very outset that,

formerly, school requirements went much further in this

respect than nowadays, when we scarcely meet with a scholar

even in the upper classes who knows Latin and Greek perfectly."

It is just this fact that Einstein regards as a sign of

improvement and a result of examining the true aims of a school.

He continued : "Man must be educated to 'react delicately' ;

he is to acquire and develop 'intellectual muscles' ! And

the methods of language drill are much less suited to this

purpose than those of a more general training that gives greatest

weight to a sharpening of one's own powers of reflection.

Naturally, the inclination of the pupil for a particular profession

must not be neglected, especially in view of the circumstance

that such inclination usually asserts itself at an early age,

being occasioned by personal gifts, by examples of other

members of the family, and by various circumstances that affect

the choice of his future life-work.

"That is why I support the

introduction into schools, particularly schools devoted to

classics, of a division into two branches at, say, the fourth

form, so that at this stage the young pupil has to decide in

favour of one or other of the courses. The elementary foundation

to the fourth form may be made uniform for all, as they are

concerned with factors on education that are scarcely open to

the danger of being exaggerated in any one direction. If

the pupil finds that he has a special interest in what are

called humaniora by the educationist, let him by all means

continue along the road of Latin and Greek, and, indeed,

without being burdened by tasks that, owing to his disposition,

oppress or alarm him."

"You are referring," I interposed, "to the distress which

pupils feel in the time allotted to mathematics. There

are actually people of considerable intelligence who seem to be

smitten with absolute stupidity when confronted with mathematics,

and whose school-life becomes poisoned owing to the

torment caused by this subject. There are many cases of

living surgeons, lawyers, historians, and

littérateurs, who, till

late in life, are visited by dreams of their earlier mathematical

ordeals.

"Their horror has a very real foundation, for, whereas

the pupil who is bad at Latin yet manages to get an idea of

the language, and he who is weak in history has at least a notion

of what is being discussed, the one who is unmathematical by

nature has to worry his way through numberless lessons in

a subject which is entirely incomprehensible to him, as if

belonging to another world and being presented to him in a

totally strange tongue. He is expected to answer questions,

the sense of which he cannot even guess, and to solve problems,

every word and every figure of which glares at him like a

sphinx of evil omen. Sitting on each side of him are pupils

to whom this is merely play, and some of whom could complete

the whole of school mathematics within a few months at express

rate. This leads to a contrast between the pupils, which may

press with tragical force on the unfortunate member throughout

his whole school existence. That is why a reform is to be

welcomed that sifts out in time those who should be separated

from the rest, and which adapts the school curriculum as closely

as possible to individual talents."

Einstein called my attention to the fact that this division

had already been made in many schools in foreign countries, as

in France and in Denmark, although not so exclusively as

suggested by him. "Moreover," he added, "I am by no

means decided whether the torments that you mentioned are

founded primarily on absence of talent in the pupil. I feel

much more inclined to throw the responsibility in most cases

on the absence of talent in the teacher. Most teachers waste

their time by asking questions which are intended to discover

what a pupil does not know, whereas the true art of questioning

has for its purpose to discover what the pupil knows or

is capable of knowing.

"Whenever sins of this sort are committed -- and they occur

in all branches of knowledge -- the

personality of the teacher is mostly at fault. The results of

the class furnish an index for the quality of the preceptor.

All things being taken into consideration, the average of

ability in the class moves, with only slight fluctuations,

about mean values, with which tolerably satisfactory results

may be obtained. If the progress of the class is not up to

this standard, we must not speak of a bad year but rather

of an inefficient instructor.

"It may be assumed that, as a

rule, the teacher understands the subject with which he is

entrusted, and has mastered its content, but not that he

knows how to impart his information in an interesting manner.

This is almost always the source of the trouble. If the teacher

generates an atmosphere of boredom, the progress is stunted

in the suffocating surroundings. To know how to teach is to

be able to make the subject of instruction interesting, to

present it, even if it happens to be abstract, so that the soul

of the pupil resonates in sympathy with that of his instructor,

and so that the curiosity of the pupil is never allowed to wane."

I replied, "That is in itself an ideal postulate. If we assume it to

be fulfilled, how do you wish to see the subjects distributed in

the curriculum ?"

"We must leave the detailed discussion of this question

for another occasion. One of the main points would be the

economy of time ; all that is superfluous, vexatious, and only

intended as a drill must be dropped. At present the aim of

the whole course is the leaving certificate. This test must be

given up !"

"Is that serious. Professor ? Do you wish to do away

with the examination for matriculation ?"

"Exactly. For it is like some fearful monster guarding

our exit from school, throwing its shadow far ahead, and

compelling teacher and pupil to work incessantly towards

an artificial show of knowledge. This examination has been

elevated by forcible means to a level which the violently

drilled candidates can keep only for a few hours, and is then

lost to sight for ever. If it is eliminated, it will carry away

with it this painful drilling of the memory ; it will no longer

be necessary to hammer in for years what will be entirely

forgotten within a few months, and what deserves to be

forgotten. Let us return to Nature, which upholds the principle

of getting the maximum amount of effect from the minimum

of effort, whereas the matriculation test does exactly the

opposite."

"Yes, but who is then to be allowed to enter the university ?"

"Every one who has shown himself to be capable not only

in a crucial test of an accidental kind, but in his whole

behaviour. The teacher will be the judge of this, and if he does

not know who is qualified, he again is to be blamed. He will

find it so much the easier to decide who is sufficiently advanced

to obtain a leaving certificate, in proportion as the curriculum

has weighed less on the minds of the young people. Six hours

a day should be ample --- four at school and two for home-work ;

that should be the maximum. If this should appear too little

to you, I must ask you to bear in mind that a young mind is

being subjected to strain even in leisure hours, as it has to

receive a whole world of perceptions. And if you ask how the

steadily increasing curriculum is to be covered in this very

moderate number of hours, my answer is : Throw all that is

unnecessary overboard !

"I count as unnecessary the major

part of the subject that is called 'Universal History,' and

which is, as a rule, nothing more than a blurred mass of history

compressed into dry tables of names and dates. This subject

should be brought within the narrowest possible limits, and

should be presented only in broad outline, without dates having

to be crammed. Leave as many gaps as you like, especially

in ancient history ; they will not make themselves felt in our

ordinary existences. In nowise can I regard it as a

misfortune if the pupil learns nothing of Alexander the Great, and

of the dozens of other conquerors whose documentary remains

burden his memory like so much useless ballast. If he is to

get a glimpse of the grey dawn of time, let him be spared from

Cyrus, Artaxerxes, and Vercingetorix, but rather tell him

something of the pioneers of civilization, Archimedes, Ptolemy,

Hero, Appolonius, and of inventors and discoverers, so that

the course does not resolve into a series of adventures and

massacres."

"Would it not be expedient," I interrupted, "to take

some of the history time to branch off into an elementary

treatment of the real evolution of the state, including sociology

and the legal code ?"

Einstein does not consider this desirable, although he himself

is deeply interested in all manifestations of public life.

He does not favour an elementary political training received

at school, presumably above all owing to the fact that in this

branch the instruction cannot be removed from official

influences, and because political questions require the attention

of a mature mind. His picture of how a youth is to meet the

requirements of modern life is something quite different, far

removed from all theories. His whole efforts are directed at

finding a means of counteracting the tendency to overburden

one side of the youthful mind. "I should demand the introduction

of compulsory practical work. Every pupil must

learn some handicraft. He should be able to choose for

himself which it is to be, but I should allow no one to grow up

without having gained some technique, either as a joiner,

bookbinder, locksmith, or member of any other trade, and

without having delivered some useful product of his trade."

"Do you attach greater importance to the technique itself

or to the feeling of social relationship with the broad masses of

the people which it engenders ?"

"Both factors are equally important to me," said Einstein,

"and others become added to these which help to justify my

wish in this respect. The handiwork need not be used as a

means of earning money by the pupil of the secondary school,

but it will enlarge and make more solid the foundation on

which he will rest as an ethical being. In the first place, the

school is not to produce future officials, scholars, lecturers,

barristers, and authors, but human beings, not merely mental

machines. Prometheus did not begin his education of mankind

with astronomy, but by teaching the properties of fire

and its practical uses ..."

"This brings to my mind another analogy," I continued,

"namely, that of the old Meistersinger, who were, all of them,

expert smiths, tinkers, or shoemakers, and yet succeeded in

building a bridge to the arts. And at bottom, the sciences,

too, belong to the category of free arts. Yet, a difficulty seems

to me to arise. In demanding a compulsory handicraft, you

lay stress on practical use, whereas in your other remarks you

declared science in itself as being utterly independent of

practice."

"I do this," replied Einstein, "only when I speak of the

ultimate aims of pure research, that is, of aims that are visible

to only a vanishing minority. It would be a complete

misconception of life to uphold this point of view and to expect

its regulative effectiveness in cases in which we are dealing

only with the preliminaries of science. On the contrary, I

maintain that science can be taught much more practically

at schools than it is at present when bookwork has the upper

hand.

"For example, to return to the question of mathematical

teaching : it seems to me to be almost universally at fault, if

only for the reason that it is not built up on what is practically

interesting, what appeals directly to the senses, and what can

be seized intuitively. Child-minds are fed with definitions

instead of being presented with what they can grasp, and they

are expected to be able to understand purely conceptual things,

although they have had no opportunity given them of arriving

at the abstract by way of concrete things.

"It is very easy to do the latter. The first beginnings

should not be taught in the

schoolroom at all, but in open Nature. A boy should be shown

how a meadow is measured and compared with another. His

attention must be directed to the height of a tower, to the

length of his shadow at various times, to the corresponding

altitude of the sun ; by this means he will grasp the mathematical

relationships much more rapidly, more surely, and

with greater zeal, than if words and chalk-marks are used to

instil into him the conceptions of dimensions, of angles, or

perchance of some trigonometrical function.

"What is the

actual origin of such branches of science ? They are derived

from practice, as, for example, when Thales first measured the

height of the pyramids with the help of a short rod, which he

set up at the ultimate point of the pyramid's shadow. Place

a stick in the boy's hand and lead him on to make experiments

with it by way of a game, and if he is not quite devoid of sense,

he will discover the thing for himself. It will please him to have

discovered the height of the tower without having climbed it,

and this is the first thrill of the pleasure which he feels later

when he learns the geometry of similar triangles and the

proportionality of their sides."

"In the matter of physics," pursued Einstein, "the first

lessons should contain nothing but what is experimental and

interesting to see. A pretty experiment is in itself often more

valuable than twenty formulæ extracted from our minds ; it is

particularly important that a young mind that has yet to find

its way about in the world of phenomena should be spared from

formulæ altogether. In his physics they play exactly the

same weird and fearful part as the figures of dates in Universal

History. If the experimenter is ingenious and expert, this

subject may be begun as early as in the middle forms, and one

may then count on a responsiveness that is rarely observable

during the hours of exercise in Latin grammar."

"This leads me," said Einstein, "to speak in this connexion

of a means of education that has so far been used only

by way of trial in class-teaching, but from an improved

application of which I expect fruitful results later. I mean the

school cinema. The triumphal march of the cinematograph

will be continued into pædagogic regions, and here it will have

a chance to make good the wrongs in thousands of picture shows

showing absurd, immoral, and melodramatic subjects. By

means of the school-film, supplemented by a simple apparatus

for projection, it would be possible firstly to infuse into certain

subjects, such as geography, which is at present wound off

organ-like in the form of dead descriptions, the pulsating life

of a metropolis. And the lines on a map will gain an entirely

new complexion in the eyes of the pupil, if he learns, as if during

a voyage, what they actually include, and what is to be read

between them.

"An abundance of information is imparted by

the film, too, if it gives an accelerated or retarded view of such

things as a plant growing, an animal's heart beating, or the

wing of an insect moving.

"The cinema seems to me to have a

still more important function in giving pupils an insight into

the most important branches of technical industry, a knowledge

of which should become common property. Very few

hours would suffice to impress permanently on the schoolboy's

mind how a power-station, a locomotive, a newspaper, a book,

or a coloured illustration is produced, or what takes place in

an electrical plant, a glass factory, or a gas-works. And, to

return to natural science, many of the rather difficult experiments

that cannot be shown by means of school apparatus

may be shown with almost as great clearness on a film.

"Taken

all in all, the redeeming word in school-teaching is, for me :

an increased appeal to the senses. Wherever it is possible,

learning must become living, and this principle will predominate

in future reforms of school-teaching."

University study was only touched on lightly during this

talk. It has become known that Einstein is a very strong

supporter of the principle of free learning, and that he would

prefer to dispense entirely with the regular documents of

admission which qualify holders to attend lecture courses. This

is to be interpreted as meaning that as soon as anyone desirous

of furthering his studies has demonstrated his fitness to follow

the lecturer's reasoning by showing his ability in class exercises

or in the laboratory, he should be admitted immediately.

Einstein would not demand the usual certificate of "general

education," but only of fitness for the special subject,

particularly as, in his own experience, he has frequently found

the cleverest people and those with the most definite aims to

be prone to one-sidedness. According to this, even the intermediate

schools should be authorized to bestow a certificate

of fitness to enter on a course in a single definite subject as

soon as the pupil has proved himself to have the necessary

ability. If he earlier spoke in favour of abolishing the matriculation

examination, this is only an indication of his effort to

burst open the portals of higher education for every one.

Nevertheless, I remarked that, in the course of university work

itself, he is not in favour of giving up all regulation concerning

the ability of the student --- at least, not in the case of those who

intend to devote themselves to instruction later. He does not

desire an intermediate examination (in the nature of the

tentamen physicum of doctors), but he considers it profitable

for the future schoolmaster to have an opportunity early in

his course to prove his fitness for teaching. In this matter,

too, Einstein reveals his affectionate interest in the younger

generation, whose development is threatened by nothing so

much as by incapable teachers : the sum of these considerations

is that the pupil is examined as little as possible, but

the teacher so much the more closely. A candidate for the

teaching profession, who in the early stages of his academic

career fails to show his fitness, his individual facultas docendi,

should be removed from the university.

There can be no doubt but that Einstein has a claim to

be heard as an authority on these questions. There are few

in the realm of the learned in whose faces it is so clearly

manifest that they are called to excite a desire for knowledge

by means of the living word, and to satisfy this desire. If

great audiences assemble around him, if so many foreign

academies open their arms to him to make him their own,

these are not only signs of a magnetic influence that emanates

from the famous discoverer, but they are indications that he

is far famed as a teacher with a captivating personality.

Let us consider what this signifies in his profession.

Philosophers, historians, lawyers, doctors, and theologians have at

their disposal innumerable words which they merely need to

pronounce to get into immediate contact with their audiences.

In Einstein's profession, theoretical physics, man disappears ;

it leaves no scope for the play of emotion ; its implement

mathematics --- and what an instrument it is ! --- bristles with

formal difficulties, which can be overcome only by means of

symbols and by using a language which has no means of

displaying eloquence, being devoid of expression, emotion,

and regular periods.

Yet here we have a physicist, a mathematician, whose first

word throws a charm over a great crowd

of people, and who extracts from their minds, so to speak,

what, in reality, he alone works out before them. He does

not adhere closely to written pages, nor to a scheme which

has been prepared beforehand in all its details ; he develops

his subject freely, without the slightest attempt at rhetoric,

but with an effect which comes of itself when the audience

feels itself swept along by the current. He does not need

to deliver his words passionately, as his passion for teaching

is so manifest. Even in regions of thought in which usually

only formulæ, like glaciers, give an indication of the height,

he discovers similes and illustrations with a human appeal,

by the aid of which he helps many a one to conquer the

mountain sickness of mathematics.

His lectures betray two

factors that are rarely found present in investigators of abstract

subjects ; they are temperament and geniality.

He never talks as if in a monologue or as if addressing empty space.

He always speaks like one who is weaving threads of some

idea, and these become spun out in a fascinating way that

robs the audience of the sense of time. We all know that no

iron curtain marks the close of Einstein's lecture ; anyone

who is tormented by some difficulty or doubt, or who desires

illumination on some point, or has missed some part of the

argument, is at liberty to question him. Moreover, Einstein

stands firm through the storm of all questions. On the very

day on which the above conversation took place he had come

straight from a lecture on four-dimensional space, at the

conclusion of which a tempest of questions had raged about him.

He spoke of it not as of an ordeal that he had survived, but

as of a refreshing shower. And such delights abound in his

teaching career.

It was the last lecture before his departure for Leyden

(in May 1920), where the famous faculty of science, under the

auspices of the great physicist Lorentz, had invited him to

accept an honorary professorship. This was not the first

invitation of this kind, and will not be the last, for distinctions

are being showered on him from all parts of the world. It

is true that the universities who confer a degree on him

honoris causa are conferring a distinction on themselves, but

Einstein frankly acknowledges the value of these honours,

which he regards as referring only to the question in hand,

and not the person. It gives him pleasure on account of the

principle involved being recognized, and he regards himself

essentially only as one whom fate has ordained as the personal

exponent of these principles.

What this life of hustle and bustle about a scientist signifies

is perhaps more apparent to me, who have a modest share

in these conversations, than to Einstein himself, for I am an

old man who -- unfortunately -- have to think back a long way

to my student days, and can set up comparisons which are

out of reach of Einstein. Formerly, many years ago, but in

my own time, there was an auditorium maximum which only

one man could manage to fill with an audience, namely, Eugen

Dühring, the noted scholar, who was doomed to remain a

lecturer inasmuch as he went under in his quarrels with

confrères of a higher rank. But before he made his onslaught

against Helmholtz, he was regarded as a man of unrivalled

magnetic power, for his philosophical and economical lectures

gathered together over three hundred hearers, a record

number in those times. Nowadays, in the case of Einstein,

four times this number has been surpassed, a fact which has

brought into circulation the playful saying : "One can never

miss his auditorium ; whither all are hastening, that is the

goal !"

To make just comparisons, we must take account of

the faithfulness of the assembled crowd, as well as its number.

Many an eminent scholar has in earlier times had reason to

declare, like Faust [I,

624] : "I had the power to attract you, yet had

no power to hold you." Helmholtz began regularly every

term with a crowded lecture-hall, but in a short time he found

himself deserted, and he himself was well aware that no

magnetic teaching influence emanated from him.

There is

yet another case in university history of a brilliant personality

who, from similar flights of ecstasy, was doomed to disappointment.

I must mention his name, which, in this connexion,

will probably cause great surprise, namely, Schiller ! He had

fixed his first lecture in history at Jena, to which he was

appointed, and had prepared for an audience of about a

hundred students. But crowd upon crowd hustled along, and

Schiller, who saw the oncoming stream from his window, was

overcome with the impression that there was no end to it.

The whole street took alarm, for at first it was imagined that

a fire had broken out, and at the palace the watch was called

out -- yet, a little later in the course, there was a depressing

ebb of the tide, after the first curiosity had been appeased ;

the audience gradually vanished into thin air, a proof of the

fact that the nimbus of a name does not suffice to maintain

the interest between the lecturer's desk and the audience.

I mentioned this example at the time when Einstein's gift

for teaching had gradually increased the number of his hearers

to the record figure of 1200, yet I did not on this occasion

detect any inordinate joy in him about his success. I gained

the impression that he had strained his voice in the vast hall.

His mood betrayed in consequence a slight undercurrent of

irritation. In an access of scepticism he murmured the words,

"A mere matter of fashion." I cannot imagine that he was

entirely in earnest. It goes without saying that I protested

against the expression. But, even if there were a particle of

truth in it, we might well be pleased to find such a fashion

in intellectual matters, one that persists so long and promises

to last. The world would recover its normal healthy state

if fashions of this kind were to come into full swing. It is,

of course, easy to understand on psychological grounds that

Einstein himself takes up a sort of defensive position against

his own renown, and that he occasionally tries to attack it

by means of sarcasm, seeing that he cannot find serious

arguments to oppose it.

Whether Einstein's ideas and proposals concerning

educational reform will be capable of realization throughout is a

question that time alone can answer. We must make it clear

to ourselves that, if carried out along free-thinking lines, they

will demand certain sacrifices, and it depends on the apportionment

of these sacrifices as to what the next, or the following,

generation will have to exhibit in the way of mental training.

An appreciable restriction will have to be imposed on the

time given to languages. It is a matter of deciding how far

this will affect the foundations that, under the collective term

humaniora, have supported the whole system of classical schools

for centuries. The fundamental ideas of reform, which, owing

to the redivision of school-hours and the economy of work, no

longer claim precedence for languages, indicate that not much

will be left of the original Latin and Greek basis.

We have noticed above that Einstein, although he does not,

in principle, oppose the old classicism, no longer expects much

good of it. But nowadays the state of affairs is such that it is

hardly a question of supporting or opposing its retention in

fragmentary form. Whoever does not support it with all his

power strengthens indirectly the mighty chorus of those who

are radically antagonistic to it. And it is a remarkable fact

that this chorus includes many would-be authorities on

languages who have influence among us because they are

champions of the cause of retaining languages.

They do not wish to rescue languages as such, but only the

German tongue ; they point to the humaniora of classical

schools, or to Humanisterei, as they call it, as the enemy and

corrupter of their language. In what sense they mean this is

obvious from their articles of faith, of which I should like to

cite a few in the original words of one of their party-leaders :

"Up to the time of the hazardous enterprise of Thomasius

(who first announced lectures in the German language in 1687)

German scholars as a body were the worst enemies of their

own tongue. --- Luther did not take his models for writing

German from the humanistic mimics who aped the old Latins.

In the case of many, including Lessing and Goethe, we observe

them making a definite attempt to shake themselves free from

the chaos of humanistic influences in Germany. --- The inheritance

of pseudo-learned concoctions of words stretches back

to pretentious humanism as do most of essential vices of learned

styles. --- The far-reaching and lasting corruption of the German

language by this poisonous Latin has its beginnings in the

humanism of the sixteenth century."

[The quotations are from

Deutsche Stilkunst by Eduard Engel (1911).

A philologist who also wrote popular works on

wide-ranging topics, Engel led

an extremely visible campaign for the use of clear and "pure" German without

foreign influence in the 1910s and '20s. Despite his role as a promoter

of Teutonic nationalism in the Weimar Republic, he was persecuted by the Nazis as

a Jew, and his memory was so completely erased that a plagiarised 1943

version of Deutsche Stilkunst by Nazi party-member Ludwig Reiners

remained in print under Reiners's name until the 1990s.]

And, quite logically, these heralds extend their attacks

along the whole academic front. For, according to their point

of view, the whole army of professors is deeply immersed in

the language slime of the traditional humanism of the Greeks

and Latins. "The whole language evil of our times," so

these

leaders say, "is at bottom due to scientists, who, in the

opinionated guise of a language caste, and without enriching our

conceptions in the slightest, seek by tinkling empty words to

give us the illusion of a new and particularly mysterious occult

science, an impression which is unfortunately often produced

on ignorant minds ... However many muddy outlets

official institutions and language associations may purge and

block up, ditch-water from ever new quagmires and drains

pours unceasingly into the stately stream of our language."

Thus the attack on the Latin and Greek language foundation

in schools identifies itself with the struggle against the

academic world as a whole, and a scholar who does defend

the classical system of education with all his might finds himself

unconsciously drifting into the ranks of the brotherhood which

in the last instance is seeking his own extermination.

This danger must not be under-estimated. It is just this

peril, so threatening to our civilization, that moves me to show

my colours frankly here. I am not a supporter of bookworm

drudgery in schools, but I feel myself impelled to use every

effort in speech and writing to combat the anti-humanists

whose password, "For our language," at root signifies

"Enemies of Science !"

We must put no weapons into their hands, and the only

means to avoid this is, in my opinion, to state our creed

emphatically and openly after the manner of almost all our

classical writers.

This creed, both as regards language and substance, is to

be understood as being based on the efficacy of the old classical

languages. It is the luminous centre of the life and work of

the men who caused Bulwer to proclaim our country

the country

of poets and thinkers. The superabundance of these is so

excessive that it is scarcely fair to mention only a few names

such as Goethe, Lessing, Schiller, Wieland, Kant, and

Schopenhauer. Our literature would be of a provincial standard and

not a world possession if this creed had not asserted its

sway at all times.

If the question is raised as to where our youth is to find

time for learning ancient languages under the present conditions

of crowded subjects, the answer is to be furnished by

improved methods of instruction. My personal point of view

is that even the older methods were not so bad. Goethe found

himself in no wise embarrassed through lack of time in acquiring

all sorts of knowledge and mental equipment, although even as

a boy of eight years he could write in Latin in a way which,

compared with the bungling efforts of the modern sixth-form

boy, seems Ciceronian. Montaigne could express himself

earlier in Latin than in French, and if he had not had this

"Latin poison" injected into his blood he would never have

become Montaigne !

It seems to me by no means impossible that the cultured

world will one day in the distant future return to the once

self-evident view of classical languages, and indeed just for

reasons of economy of time, unless the universal language so

ardently desired by Hebbel --- not to be confused with the

artificial patchwork called Esperanto --- should become a reality.

["If language had been the creation not of poetry but

of logic, we should only have one." (Hebbel:

Tagebuch, 5634)]

But even this language, at present Utopian, but one which will

help to link together the nations, will disclose the model of the

ancient languages in its structure. Scientific language of the

present day shows where the route lies ; and this route will be

made passable in spite of all the efforts of Teutonic language-saints

and assassins of humanism to block it.

The working out of ideas by research scientists leads to

enrichment of language. And since, as is quite natural, they

draw copiously on antique forms of expression, they are really

the trustees of an instruction that makes these expressions

intelligible not merely as components of an artificial language

like Volapük but as organic growths. That is how they

proceed when they carry on their research, or describe it and

lecture on their own subject.

But if they are to decide how

the school is to map out its course in actual practice, the problem

of time again becomes their chief consideration --- that is,

they feel in duty bound to give preference to what is most

important. Hence there results the wish to reduce the hours

apportioned to the language subjects as much as possible.

On this matter we have

a detailed essay by the distinguished

Ernst Mach mentioned earlier, who exposes the actual dilemma

with the greatest clearness. He treats this exceedingly

important question in all its phases, and arrives at almost the

same conclusion as Einstein. At the outset he certainly chants

a Latin psalm almost in the manner of Schopenhauer. Its

lower tones represent an elegy lamenting that Latin is no

longer the universal language among educated people, as it

was from the fifteenth to the eighteenth century. Its fitness

for this purpose is quite indisputable, for it can be adapted to

express every conception however modern or subtle it may be.

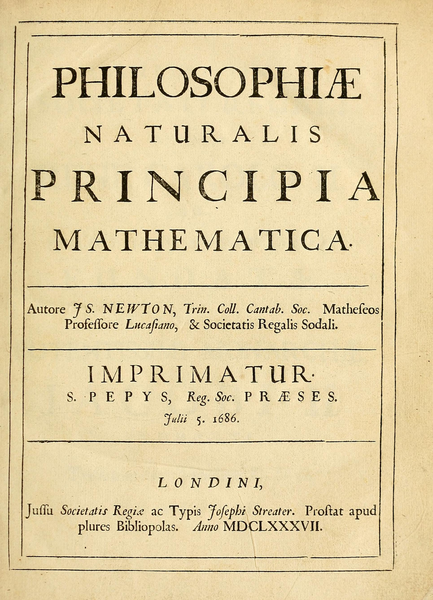

What a profusion of new conceptions was introduced into

science by Sir Isaac Newton, to all of which he succeeded in

giving correct and precise Latin names ! The natural inference

suggests itself to us that young people should learn the ancient

classical tongues -- and yet a different result is coming about ;

the modern child is to be content with understanding words

with a world-wide currency, without knowing their philological

origin.

It is not necessary to be a schoolmaster to feel the

inadequacy of this proceeding. It is true that without knowing

Arabic we can grasp the sense and meaning of the word

"Algebra," and in the same way we can extract the essence of

a number of Greek and Latin expressions without digging at

their etymological roots. But these expressions are to be

counted in hundreds and thousands, and are increasing daily,

so that we are put before the question whether, merely from

the point of view of time, it is practicable to learn them as

individual foreign terms or as natural products of a root

language with which we have once and for all become familiar.

It is scarcely necessary for me to point out that Einstein

himself is not sparing in the use of these technical expressions,

even when he is using popular language. He assumes or

introduces terms of which the following are a few examples :

continuum, co-ordinate system, dimensional, electrodynamics,

kinetic theory, transformation, covariant, heuristic, parabola,

translation, principle of equivalence, and he is quite justified

in assuming that every one is fully acquainted with such

generally accepted expressions as : gravitation, spectral

analysis, ballistic,

phoronomy, infinitesimal, diagonal, component, periphery,

hydrostatics, centrifugal, and numberless

others which are diffused through educated popular language

in all directions. Taken all together these represent a foreign

realm in which the entrant can always succeed in orientating

himself when he receives explanations, examples, or translations,

whereas with a little preliminary knowledge of the

ancient languages he immediately feels himself at home with

them ; in this we have not even taken into consideration the

general cultural value of this training in view of the access it

gives to the old literature and to Hellenic culture.

Perhaps I am going too far in adopting the attitude of

a laudator temporis acti towards Einstein's very advanced

opinion. We are here dealing with a question in which nothing

can be proved, and in which everything depends on disposition

and personal experiences. In my own case this experience

includes the fact that at a very early age, in spite of the very

discouraging school methods, I enjoyed the study of Latin and

Greek, and that I learned Horatian odes by heart, not because

I had to, but because they appealed to me, and finally that

Homer opened up a new world to me. When Einstein

expresses his abhorrence of drill, I agree with him ; but these

languages need not be taught as if we are on parade. We see

thus that it is a question of method and not of the subject

involved. Einstein gives the subject its due by recommending

a double series of classes. He allows the paths to diverge,

giving his special blessing to the group along the one without

setting up obstacles to prevent the other pilgrims from attaining

happiness in their own way.

We spoke of higher education for women, and Einstein

expressed his views which, as was to be expected, were tolerant,

and yet did not suggest those of a champion of the cause. It

was impossible to overlook the fact that in spite of his approval

he had certain reservations of a theoretical nature.

"As in all other directions," he said, "so in that of science

the way should be made easy for women. Yet it must not be

taken amiss if I regard the possible results with a certain

amount of scepticism. I am referring to certain obstacles in

woman's organization which we must regard as given by

Nature, and which forbid us from applying the same

standard of expectation to women as to men."

"You believe, then, Professor, that high achievements

cannot be accomplished by women ? To keep our attention

on science, can one not quote Madame Curie as a proof to the

contrary ?"

"Surely only as one proof of brilliant exceptions, more

of which may occur without refuting the statute of sexual

organization."

"Perhaps this will be possible after all if a sufficient time

for development be allowed. There may be much fewer

geniuses among the other sex, but there has certainly been a

concentration of talent. Or, in other words, totally ignorant

women have become much rarer. You, Professor, are

fortunate in not being in a position to compare young women

of to-day with those of forty or more years ago ! This I can

do, and just as once I found it natural that there should be

swarms of little geese and peacocks, I never recover from my

astonishment nowadays at the amount of knowledge acquired

by young womanhood. It requires a considerable effort on

my part very often to avoid being completely overshadowed

by a partner at dinner. The more this stratum of talent

increases, the more we have reason to expect a greater number

of geniuses from them in the future."

"You are given to prognostication," said Einstein, "and

calculate with probabilities which sometimes are lacking in

foundation. Increased education and even an increase of

talents are quantitative assumptions that make an inference

regarding higher quality reaching to genius appear very bold."

A passing look of ominous portent flashed over his face, and

I noticed that he was preparing to launch a sarcastic aphorism.

So it was, for the next words were :

"It is conceivable that

Nature may have created a sex without brains !"

I grasped the sense of this grotesque remark, which was in

no way to be taken literally. It was intended as an amusing

exaggeration of what he had earlier called the reason for his

failing expectation : the organic difference which, being

rooted in the physical constitution, had somewhere to express

itself on the mental plane, too. The soul of woman strong in

impulse shows a refinement of feeling of which we men are

not susceptible, whereas the greatest achievements of reason

probably depend on a preponderance of brain substance. It is

this plus beyond the normal amount that gives promise of

great discoveries, inventions, and creations. We can just

as little imagine a female Galilei, Kepler, and Descartes, as a

female Michelangelo or Sebastian Bach.

But when we think

of these extreme cases, let us also recall the balance on the

other side : although a woman could not create the differential

calculus, it was she that created Leibniz ; similarly she

produced Kant if not the Critique of Pure Reason. Woman, as

the author of all great minds, has at least a right of access to

all means of education and to all advancement that is proffered

by universities. And in this connexion Einstein expressed his

wish clearly enough.

[Not quite the Einstein one might wish ! While such sentiments were

common enough among male intellectuals, even politically radical ones,

in the early 1900s, Einstein's extreme language --- the much older and

unabashedly sexist Moszkowski calls it "grotesque" --- probably owes

its venom as much to events in his personal life as to blind acceptance of

the social status quo. Einstein's bitter divorce from the physicist Mileva Marić

was finalised in February of 1919 ; in June of the same year he married his far more

traditional cousin Elsa Löwenthal. The contempt for intelligent women

in the paragraphs above is nothing compared to that expressed in some of

Einstein's letters to Marić during the collapse of their relationship.]

One of the most discussed themes in matters touching

school education is at the present time : "the selection of

gifted pupils." It has developed into a principle that is

generally recognized by the great majority, the only point

of disagreement being in respect to the number that is to be

selected.

The idea running through it is that derived from Darwin's

theory of selection : man completes the method of selection

practised by Nature. He sifts and chooses, and allows those

that are more talented to come to the fore more rapidly and

more decidedly ; he favours their advancement and makes easy

their ascent.

This principle has really always been in existence. It

started with the distribution of prizes in ancient Olympia and

reaches to the present-day examinations that are clearly

intended as a means of selecting talents. A greater discrimination

based on a systematic search for talents was reserved for

our own day.

It was scarcely a matter of doubt to me what attitude

Einstein would take up towards this matter. I had already

heard him say hard words about the system of examinations,

and knew his leaning towards allowing each mind to develop

its power freely and naturally.

In effect, Einstein declared to me that he would hear

nothing of a breeding of talents in a sort of sporting way.

The dangers of the methods of sport would creep in and lead to

results that had only the appearance of truth. From the

results so far obtained it was impossible to come to a final

decision about it. Yet it was conceivable that a selective

process conducted along reasonable lines would in general

prove of advantage in education, particularly in the respect

that many a talent that would ordinarily become stunted

owing to its being kept in darkness would now have an

opportunity of coming to light.

This resolved itself into a talk bearing on many questions,

and of which I should like to state the main issue here. It

was specially intended to make clear the gambling method

that Einstein repudiates, and the danger of which seems still

more threatening to me than to him.

If certain pædagogues, whose creed is force, were to have

their way, the "most gifted " pupils would be able, or would

be compelled, to rush through school at hurricane speed, and,

at an age at which their fellows were still spending weary

hours at their desks, they would have to clamber to the

top-most branches of the academic tree. All things are possible,

and history even furnishes cases of such forced marches.

Luther's friend Melanchthon qualified at the age of thirteen

to enter the University of Heidelberg, and at the age of seventeen

he became a professor at Tübingen, where he gave lectures

on the most difficult problems of philosophy, as well on the

Roman and Greek writers of classical antiquity. This single

instance need only be generalized, and we have the new ideal

rising up before our astonished gaze : a race of professorial

striplings whose upper lips are scarcely darkened with the

down of youth ! It is a mere matter of making an early

discovery of the most gifted, and then raising the scaffolding

up which the precocious know-alls can climb as easily as

possible.

(Interposed query : Where are these discoverers of talent,

and how do they prove their own talent ? There was a good

opportunity for them in a case which I must here mention.

Einstein told me in another connexion that, as early as 1907,

that is, when he was still very young in years, he had not

only succeeded in successfully representing the Principle of

Equivalence, one of the main supports of the General Principle

of Relativity, but had even published it ; yet it made not the

slightest impression on the learned world. No one suspected

the far-reaching consequences, and no one pointed out this

flaming up of a new talent of the highest order. And just as

this was able to remain concealed from the learned Areopagus

of the world at that time, so a similar lack of understanding

may easily be possible on a smaller scale at school. We know

actually that among the recognized great men of science,

there were many who did only moderately well at school ;

as, for example, Humphry Davy, Robert Mayer, Justus

Liebig, and many others. Wilhelm Ostwald goes so far as to

affirm : "Boys ordained to be discoverers later in life have,

almost without exception, been bad at school ! It is just the

most gifted young people who have resisted most strongly

the form of intellectual development prescribed by the school !

Schools never cease to show themselves to be the bitter,

unrelenting enemies of genius !" --- in spite of all efforts at

selection which have always been in vogue in the guise of

advancement into higher forms.)

But the new mode of selection is intended to prevent

mistakes and oversights. Is this possible ? Do not the traces

of previous attempts inspire distrust ? There was once a

very ideal selection that had to stand the test of one of the

most eminent bodies in existence, the French Academy. Its

duty was to discover geniuses on an incomparably higher

plane. It, however, repudiated or overlooked : Molière,

Descartes, Pascal, Diderot, the two Rousseaus, Beaumarchais,

Balzac, Béranger, the Goncourts, Daudet, Emile Zola, and

many other extremely gifted people, whom it should really

have been able to find.

The only true, and at the same time necessary as well as

sufficient, breeding is carried out by Nature herself in

conjunction with social conventions, which promise the more

success the less they assume the character of incubators

and breeding establishments. If you wish to apply tests to

discover pupils of genius in any class, examine as much as

you like, excite interest and ambition, distribute prizes even,

but not for the purpose of separating at short intervals the

shrewd and needle-witted heads from the rest ; and do not

lose sight of the fact that, among those who appear as the

sheep as a result of these systematized tests to discover

ingenuity, there are many who, ten or twenty years later, will

take up their positions as men of eminent talent.

There is no essential difference between the forced promotion

of such pupils and the breeding of super-men according

to Nietzsche's recipe as exemplified by his Zarathustra.

Assuming that super-men are justified in existing at all,

they will come about of themselves, but cannot simply be

manufactured. Workmen, taken as a class, represent super-men

more definitely than an individual such as Napoleon

or Cæsar Borgia. So the "super-scholar" exists perhaps

already to-day, not as an individual phenomenon, but as a

whole, representing his class. Whoever has had experience

in these things will know that nowadays there are difficult

subjects in which it is possible to apply to pupils of fifteen

years of age tests that are far above the plane of comprehension

of pupils of the same age in former times, provided that

the average is considered, that no accidental or artificial

separation has occurred, that no pretentiously witty questions

have had to be answered, and that there has been no systematic

and inquisitive search for talent.

Let us rest satisfied if we find that the sum-total of talent

is continually on the increase. On the other hand, it is by

no means proved that we are doing civilization a service by

persisting in the impossible project of abolishing from the

world the struggle for existence prescribed by Nature. It is

an elementary fact, and one that is easy to understand, that

many talents perish unnoticed. On the other hand, observe

the long list of eminent men who fought their way upwards

out of the lowest stages of existence only to recognize that the

difficulties that have been overcome are mostly necessary

accompaniments of talent, that is, that Nature's way of

selection is to oppose obstacles and raise difficulties in order

to test their powers.

In the case of the poor lens-grinder

Spinoza and many others ranging to Béranger, who was a

waiter, what a chain of desperate experiences, yet what

triumphs ! Herschel, the astronomer, was too poor to buy

a refracting telescope, and it was just this dispensation of

poverty that made him succeed in constructing a reflecting

type composed of a mirror. Faraday, the son of a blacksmith

without means, made his way for years as a bookbinder's

apprentice. Joule, one of the founders of the mechanical

theory of heat, started as a beer-brewer. Kepler, the

discoverer of the planetary laws, was descended from a

poverty-stricken innkeeper. Of the members in Goethe's circle,

Jung-Stilling, of whom Nietzsche was so fond, was a tailor's

apprentice ; Eckermann, Goethe's intimate associate, was a

swine-herd, and Zelter was a mason. We could add many

recent names to this list, and very many more if we continue

the line backwards to Euripides, whose father was a publican

and whose mother was a vendor of vegetables. This might

serve as a basis for many reflections about the "upward course

of the talented," and about its less favourable reverse side.

For one might put the apparently paradoxical question whether

a soaring career for many or all talents is a necessity for our

civilization, or whether it would not be better to have a

substratum interspersed with talent, to cultivate a mossy

undergrowth which is to serve as nourishment for the blooming

plants of the upper layer.

Maximum is not equivalent to optimum, and we learned

elsewhere that Einstein is far removed from identifying them.

In the previous case it was a question of the problem of

population ; and in the course of the discussion he mentioned that

we are subject to an old error of calculation when we regard

it as a desirable aim to have a maximum number of human

beings on the earth. It seems, indeed, that this false

conclusion is already in process of being corrected. A beginning

is being made with new and very active organizations and

unions whose programme is to reduce the number so that an

optimum may be attainable by those left.

If we extend this line of reasoning still further, we arrive

at the depressing question whether too much might not be

done for talent, not only as regards breeding it, but also in

favouring the greatest number. It is quite possible that in

doing so, we might overlook, or take insufficient account of

the harm that might be done to the lower stratum, in that

we should be depriving it of forces which, according to the

economy of Nature, should remain and act in concealment.

This fear, as here expressed, is not shared by Einstein.

However brusquely he repudiates breeding, he speaks in

favour of smoothing the way for talent. "I believe," he said,

"that a sensible fostering of gifts is of advantage to humanity

generally and prevents injustice being done to the individual.

In great cities which give such lavish opportunities of education,

this injustice manifests itself less often ; but it occurs

so much the more in rural districts, where there are certainly

many cases of gifted youths who, if recognized as such at the

right age, would attain to an important position, but who,

together with their gifts, become stunted, nay, go to ruin, if

the principle of selection does not penetrate to their circle."

This brings us to the most difficult and most dangerous

point. The spectre of responsibility is rapping at the portals

of society, and is reminding us insistently that it is our duty

to see that no injustice be done to any talent that may be among

us. And this duty is but little removed from the demand that

it should be disburdened of the worries of daily life, for, so

the moral argument runs, talent will ripen the more surely the

less it has to combat these ceaseless disturbances of ordinary

life.

But this thesis, so evident on moral grounds, will never be

proved empirically. On the contrary, we have good reason to

suppose that necessity, the mother of invention on the broader

scale, will often in the case of the individual talent prove to be

the mother of its best results. Goethe required for his development

an unchallenged life of ease, whereas Schiller, who never

emerged from his life of misery, and who, up to the time when

he wrote Don Carlos, had not been able to earn sufficient with

his pen to buy a writing-desk, required distress to make his

genius burst into flower. Jean Paul recognized this blessing

of gloomy circumstances when he glorified poverty in his

novels. Hebbel followed him along this path by saying that it

is more fruitful to refuse the most talented person the necessities

of life than to grant them to the least gifted. For among

a hundred who have been chosen by the method of sifting,

there will be only one on the average who will receive the

certificate of excellence in the test of future generations, for

the latter use entirely different methods of sifting from that

practised by a committee of examiners who expect ready

answers to prepared questions.

This projects us on to the horns of a severe dilemma that

scarcely allows of escape. The consciousness of duty towards

the optimum expresses itself only in a maximum of assistance,

and overhears the whispered objection of reason that Nature

has also coarser means at her disposal to attain her ends;

in her own cruelty of selection she often enough proves

the truth of Menander's saying, which, freely translated,

says : to be tormented is also part of man's education.

The fact that Einstein -- with certain reservations -- favours

the giving of help to the selected few, it is for me a proof,

among many others, of his love towards his fellow-men, which

fills his heart absolutely, all questions of relativity notwithstanding.

EDUCATION

Berlinisches Gymnasium zum Grauen Kloster (postcard, ca. 1910).

Geometry students, ca. 1310. [British Library Burney 275 f. 293 r.]

Prometheus the Fire-Bringer by Ivar Johnsson. (Nyköping, Sweden)

Students at the experimental Aspatria

Agricultural College, Cumberland, 1905. Photo from the collection of

Terry Carrick.

Berlin: Humboldt University, view from Kaiser-Franz-Joseph-Platz.

Einstein had already been driven out when this photo was

taken by Otto Hagemann. (German Federal Archives Bild 146-2006-0130)

"One of the party-leaders of the many would-be authorities on

languages who have influence among us" : Prof. Eduard Engel in 1901.

At the Natural Sciences Department, University of Novi Sad. Photo by "Micki", 2011.

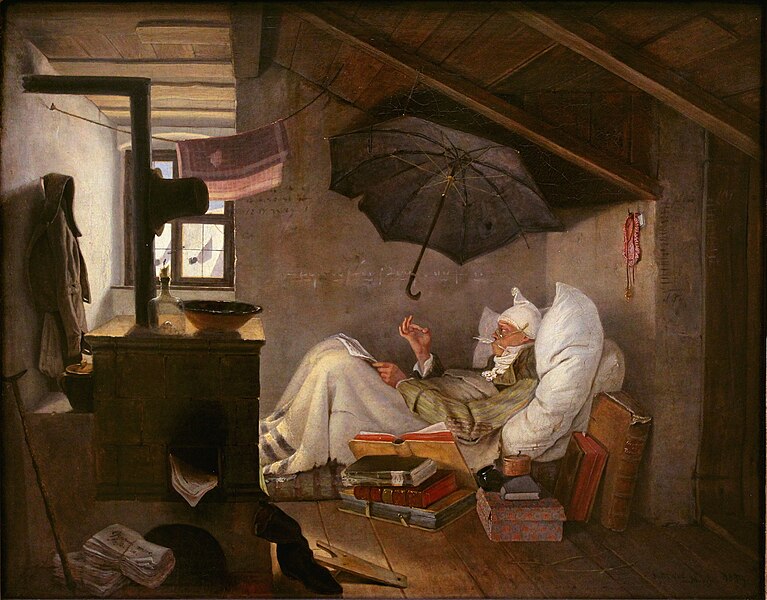

Carl Spitzweg: Der arme Poet, 1839.

Einstein at age 14.

CONTENTS: