Huck's words are in bold.

"Noon ! " says Tom, and so it was. His shadder was just a blot around his feet. We looked, and the Grinnage clock was so close to twelve the difference did n't amount to nothing. So Tom said London was right north of us or right south of us, one or t'other, and he reckoned by the weather and the sand and the camels it was north ; and a good many miles north, too ; as many as from New York to the city of Mexico, he guessed.

Jim said he reckoned a balloon was a good deal the fastest thing in the world, unless it might be some kinds of birds --- a wild pigeon, maybe, or a railroad.

But Tom said he had read about railroads in England going nearly a hundred miles an hour for a little ways, and there never was a bird in the world that could do that --- except one, and that was a flea.

"A flea? Why, Mars Tom, in de fust place he ain't a bird, strickly speakin' --- "

"He ain't a bird, eh ? Well, then, what is he ?"

"I don't rightly know, Mars Tom, but I speck he 's only jist a' animal. No, I reckon dat won't do, nuther, he ain't big enough for a' animal. He mus' be a bug. Yassir, dat 's what he is, he 's a bug."

"I bet he ain't, but let it go. What 's your second place ?"

"Well, in de second place, birds is creturs dat goes a long ways, but a flea don't."

'' He don't, don't he ? Come, now, what is a long distance, if you know ?"

"Why, it 's miles, and lots of 'em --- anybody knows dat."

"Can't a man walk miles ?"

"Yassir, he kin."

" As many as a railroad ?"

"Yassir, if you give him time."

''Can't a flea?"

"Well, --- I s'pose so --- ef you gives him heaps of time."

"Now you begin to see, don't you, that distance ain't the thing to judge by, at all; it 's the time it takes to go the distance in that counts, ain't it ?"

"Well, hit do look sorter so, but I would n't 'a' b'lieved it, Mars Tom."

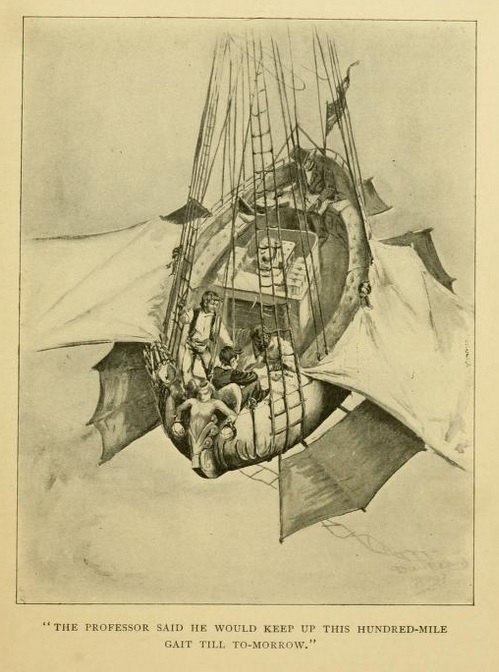

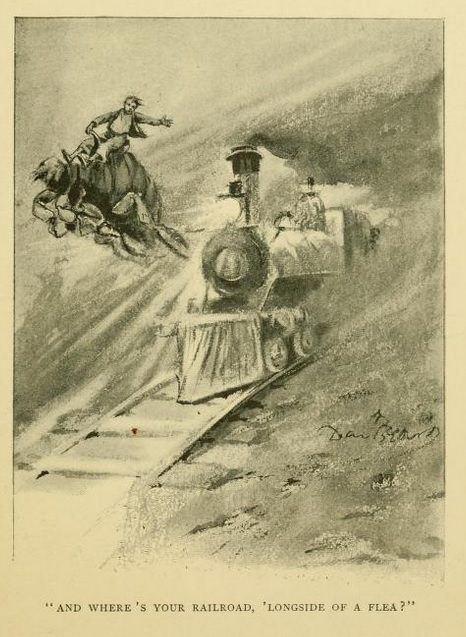

"'It 's a matter of proportion, that 's what it is; and when you come to gauge a thing's speed by its size, where 's your bird and your man and your railroad, alongside of a flea ?

"The fastest man can't run more than about ten miles in an hour --- not much over ten thousand times his own length. But all the books says any common ordinary third-class flea can jump a hundred and fifty times his own length; yes, and he can make five jumps a second too, --- seven hundred and fifty times his own length, in one little second --- for he don't fool away any time stopping and starting --- he does them both at the same time; you 'll see, if you try to put your finger on him.

"Now that 's a common, ordinary, third-class flea's gait; but you take an Eyetalian first-class, that 's been the pet of the nobility all his life, and has n't ever knowed what want or sickness or exposure was, and he can jump more than three hundred times his own length, and keep it up all day, five such jumps every second, which is fifteen hundred times his own length.

"Well, suppose a man could go fifteen hundred times his own length in a second --- say, a mile and a half. It 's ninety miles a minute; it 's considerable more than five thousand miles an hour. Where 's your man now ? --- yes, and your bird, and your railroad, and your balloon ? Laws, they don't amount to shucks 'longside of a flea. A flea is just a comet b'iled down small."

Jim was a good deal astonished, and so was I. Jim said ---

"Is dem figgers jist edjackly true, en no jokin' en no lies, Mars Tom ?"

''Yes, they are; they 're perfectly true."

"Well, den, honey, a body 's got to respec' a flea. I ain't had no respec' for um befo', sca'sely, but dey ain't no gittin' roun' it, dey do deserve it, dat 's certain."

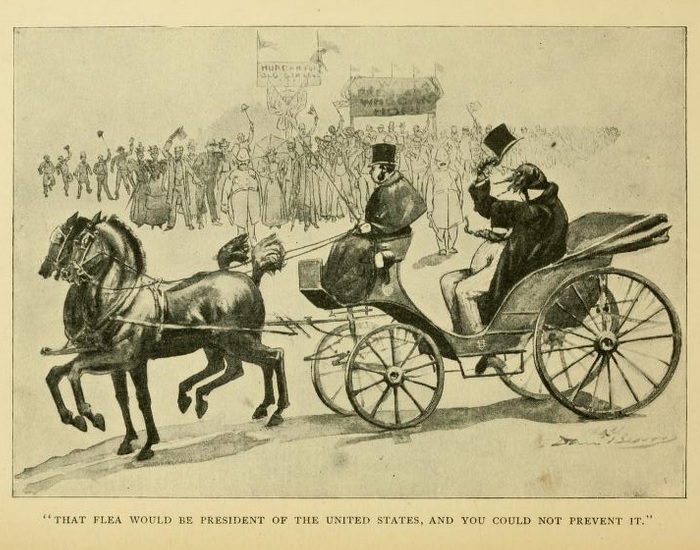

"Well, I bet they do. They 've got ever so much more sense, and brains, and brightness, in proportion to their size, than any other cretur in the world. A person can learn them 'most anything; and they learn it quicker than any other cretur, too. They 've been learnt to haul little carriages in harness, and go this way and that way and t' other way according to their orders; yes, and to march and drill like soldiers, doing it as exact, according to orders, as soldiers does it. They 've been learnt to do all sorts of hard and troublesome things.

"S'pose you could cultivate a flea up to the size of a man, and keep his natural smartness a-growing and a-growing right along up, bigger and bigger, and keener and keener, in the same proportion --- where 'd the human race be, do you reckon ? That flea would be President of the United States, and you could n't any more prevent it than you can prevent lightning."

"My lan', Mars Tom, I never knowed dey was so much to de beas'. No, sir, I never had no idea of it, and dat 's de fac'."

'"There 's more to him, by a long sight, than there is to any other cretur, man or beast, in proportion to size. He's the interestingest of them all. People have so much to say about an ant's strength, and an elephant's, and a locomotive's. Shucks, they don't begin with a flea. He can lift two or three hundred times his own weight. And none of them can come anywhere near it.

"And moreover, he has got notions of his own, and is very particular, and you can't fool him; his instinct, or his judgment, or whatever it is, is perfectly sound and clear, and don't ever make a mistake. People think all humans are alike to a flea. It ain't so. There 's folks that he won't go near, hungry or not hungry, and I 'm one of them. I 've never had one of them on me in my life."

"Mars Tom!"

"It 's so ; I ain't joking."

"Well, sah, I hain't ever heard de likes o' dat, befo'."

Jim could n't believe it, and I could n't ; so we had to drop down to the sand and git a supply and see. Tom was right They went for me and Jim by the thousand, but not a one of them lit on Tom. There war n't no explaining it, but there it was and there war n't no getting around it. He said it had always been just so, and he 'd just as soon be where there was a million of them as not ; they 'd never touch him nor bother him.

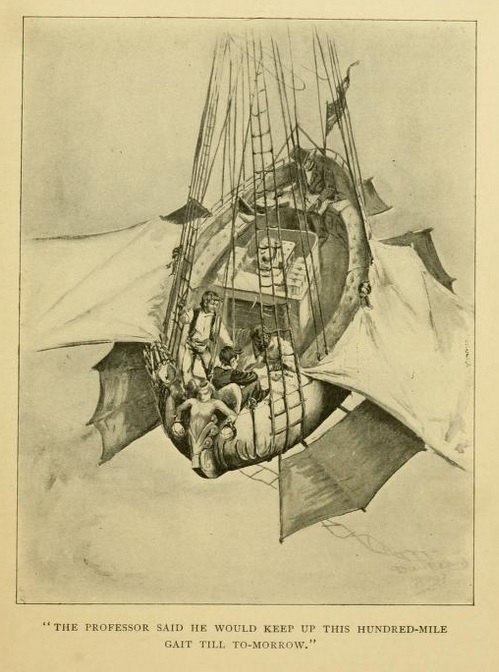

We went up to the cold weather to freeze 'em out, and stayed a little spell, and then come back to the comfortable weather and went lazying along twenty or twenty-five miles an hour, the way we 'd been doing for the last few hours. The reason was, that the longer we was in that solemn, peaceful desert, the more the hurry and fuss got kind of soothed down in us, and the more happier and contented and satisfied we got to feeling, and the more we got to liking the desert, and then loving it. So we had cramped the speed down, as I was saying, and was having a most noble good lazy time, sometimes watching through the glasses, sometimes stretched out on the lockers reading, sometimes taking a nap.

It did n't seem like we was the same lot that was in such a state to find land and git ashore, but it was. But we had got over that --- clean over it. We was used to the balloon, now, and not afraid any more, and did n't want to be anywheres else. Why, it seemed just like home ; it 'most seemed as if I had been born and raised in it, and Jim and Tom said the same. And always I had had hateful people around me, a-nagging at me, and pestering of me, and scolding, and finding fault, and fussing and bothering, and sticking to me, and keeping after me, and making me do this, and making me do that and t'other, and always selecting out the things I did n't want to do, and then giving me Sam Hill because I shirked and done something else, and just aggravating the life out of a body all the time ; but up here in the sky it was so still and sunshiny and lovely, and plenty to eat, and plenty of sleep, and strange things to see, and no nagging and no pestering, and no good people, and just holiday all the time. Land, I war n't in no hurry to git out and buck at civilization again ...

We had supper, and that night was one of the prettiest nights I ever see. The moon made it just like daylight, only a heap softer ; and once we see a lion standing all alone by himself, just all alone on the earth, it seemed like, and his shadder laid on the sand by him like a puddle of ink. That 's the kind of moonlight to have.

Mainly we laid on our backs and talked ; we did n't want to go to sleep. Tom said we was right in the midst of the Arabian Nights, now. He said it was right along here that one of the cutest things in that book happened ; so we looked down and watched while he told about it, because there ain't anything that is so interesting to look at as a place that a book has talked about. It was a tale about a camel-driver that had lost his camel, and he come along in the desert and met a man, and says ---

''Have you run across a stray camel to-day ?"

And the man says ---

''Was he blind in his left eye ?"

''Yes."

"Had he lost an upper front tooth ?"

"Yes."

"Was his off hind leg lame ?"

"Yes."

"Was he loaded with millet-seed on one side and honey on the other ?"

"Yes, but you need n't go into no more details --- that 's the one, and I 'm in a hurry. Where did you see him ?"

"I hain't seen him at all," the man says.

"Hain't seen him at all ? How can you describe him so close, then ?"

''Because when a person knows how to use his eyes, everything has got a meaning to it ; but most people's eyes ain't any good to them. I knowed a camel had been along, because I seen his track. I knowed he was lame in his off hind leg because he had favored that foot and trod light on it, and his track showed it. I knowed he was blind on his left side because he only nibbled the grass on the right side of the trail. I knowed he had lost an upper front tooth because where he bit into the sod his teeth-print showed it. The millet-seed sifted out on one side --- the ants told me that ; the honey leaked out on the other --- the flies told me that. I know all about your camel, but I hain't seen him."

Jim says ---

''Go on. Mars Tom, hit 's a mighty good tale, and powerful interestin'."

"That 's all," Tom says.

''All?'' says Jim, astonished. "What 'come o' de camel ?"

"I don't know."

"Mars Tom, don't de tale say ? "

" No."

Jim puzzled a minute, then he says ---

"Well ! Ef dat ain't de beatenes' tale ever I struck. Jist gits to de place whah de intrust is gittin' red-hot, en down she breaks. Why, Mars Tom, dey ain't no sense in a tale dat acts like dat. Hain't you got no idea whether de man got de camel back er not ?"

"No, I have n't."

I see, myself, there war n't no sense in the tale, to chop square off, that way, before it come to anything, but I war n't going to say so, because I could see Tom was souring up pretty fast over the way it flatted out and the way Jim had popped onto the weak place in it, and I don't think it 's fair for everybody to pile onto a feller when he 's down. But Tom he whirls on me and says ---

''What do you think of the tale ?"

Of course, then, I had to come out and make a clean breast and say it did seem to me, too, same as it did to Jim, that as long as the tale stopped square in the middle and never got to no place, it really war n't worth the trouble of telling.

Tom's chin dropped on his breast, and 'stead of being mad, as I reckoned he 'd be, to hear me scoff at his tale that way, he seemed to be only sad ; and he says ---

"Some people can see, and some can't --- just as that man said. Let alone a camel, if a cyclone had gone by, you duffers would n't 'a' noticed the track."

I don't know what he meant by that, and he did n't say ; it was just one of his irrulevances, I reckon --- he was full of them, sometimes, when he was in a close place and could n't see no other way out --- but I did n't mind. We 'd spotted the soft place in that tale sharp enough, he could n't git away from that little fact. It graveled him like the nation, too, I reckon, much as he tried not to let on.

Jim was thinking to himself, and at last he says ---

"Mars Tom, we 's mos' to de end er de Desert now, I speck."

''Why?"

"Well, hit stan' to reason we is. You knows how long we 's been a-skimmin' over it. Mus' be mos' out o' san'. Hit 's a wonder to me dat it 's hilt out as long as it has."

''Shucks, there 's plenty sand, you need n't worry."

"Oh, I ain't a-worryin', Mars Tom, only wonderin', dat 's all. De Lord 's got plenty san' I ain't doubtin' dat, but nemmine. He ain' gwyne to was'e it jist on dat account ; en I allows dat dis Desert 's plenty big enough now, jist de way she is, en you can't spread her out no mo' 'dout was'in san'."

"Oh, go 'long ! we ain't much more than fairly started across this Desert yet. The United States is a pretty big country, ain't it ? Ain't it, Huck ?"

"Yes," I says, ''there ain't no bigger one, I don't reckon."

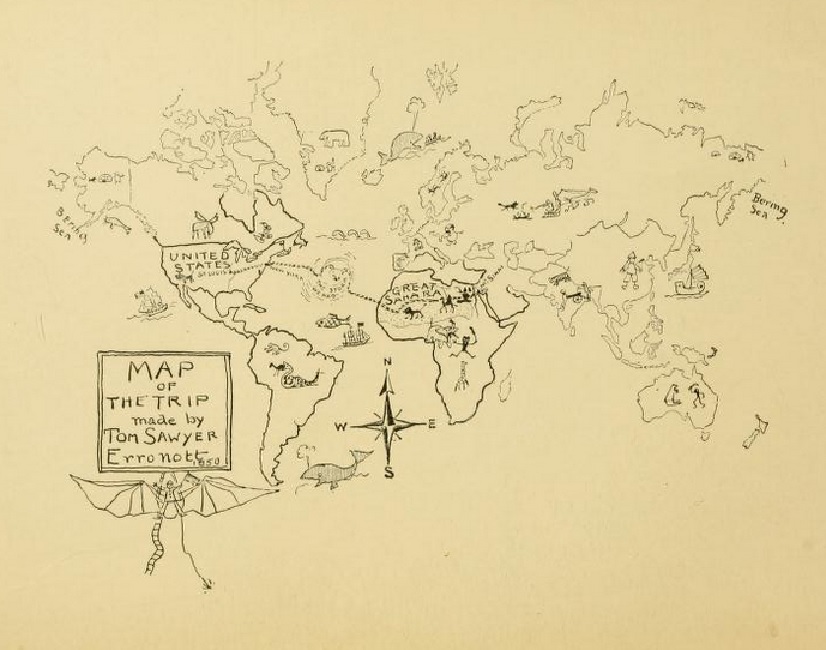

''Well," he says, ''this Desert is about the shape of the United States, and if you was to lay it down on top of the United States, it would cover the Land of the Free out of sight like a blanket. There 'd be a little corner sticking out, up at Maine and away up northwest, and Florida sticking out like a turtle's tail, and that 's all. We 've took California away from the Mexicans two or three years ago, so that part of the Pacific coast is ours, now, and if you laid the Great Sahara down with her edge on the Pacific, she would cover the United States and stick out past New York six hundred miles into the Atlantic Ocean."

I says ---

"Good land ! have you got the documents for that, Tom Sawyer ?"

"Yes, and they 're right here, and I 've been studying them. You can look for yourself. From New York to the Pacific is 2,600 miles. From one end of the Great Desert to the other is 3,200. The United States contains 3,600,000 square miles, the Desert contains 4,162,000. With the Desert's bulk you could cover up every last inch of the United States, and in under where the edges projected out, you could tuck England, Scotland, Ireland, France, Denmark, and all Germany. Yes, sir, you could hide the Home of the Brave and all of them countries clean out of sight under the Great Sahara, and you would still have 2,000 square miles of sand left."

"Well," I says, "it clean beats me. Why, Tom, it shows that the Lord took as much pains makin' this Desert as makin' the United States and all them other countries."

Jim says --- "Huck, dat don' stan' to reason. I reckon dis Desert wa' n't made, at all. Now you take en look at it like dis --- you look at it, and see ef I 's right. What 's a desert good for? 'T ain't good for nuthin'. Dey ain't no way to make it pay. Hain't dat so, Huck ?"

"Yes, I reckon."

''Hain't it so, Mars Tom ?"

"I guess so. Go on."

''Ef a thing ain't no good, it 's made in vain, ain't it?"

"Yes."

''Now, den! Do de Lord make anything in vain ? You answer me dat."

"Well --- no, He don't."

"Den how come He make a desert ?"

"Well, go on. How did He come to make it?"

''Mars Tom, I b'lieve it uz jes like when you 's buildin' a house ; dey 's allays a lot o' truck en rubbish lef' over. What does you do wid it ? Doan' you take en k'yart it off en dump it into a ole vacant back lot ? 'Course. Now, den, it 's my opinion hit was jes like dat, dat de Great Sahara war n't made at all, she jes happen'."

I said it was a real good argument, and I believed it was the best one Jim ever made. Tom he said the same, but said the trouble about arguments is, they ain't nothing but theories, after all, and theories don't prove nothing, they only give you a place to rest on a spell, when you are tuckered out butting around and around trying to find out something there ain't no way to find out. And he says ---

"There 's another trouble about theories: there 's always a hole in them somewheres, sure, if you look close enough. It 's just so with this one of Jim's. Look what billions and billions of stars there is. How does it come that there was just exactly enough star-stuff, and none left over ? How does it come there ain't no sand-pile up there ?"

But Jim was fixed for him and says ---

''What 's de Milky Way ? Dat 's what I wants to know. What 's de Milky Way ? Answer me dat !"

In my opinion that was just a sockdologer. It 's only an opinion, it 's only my opinion and others may think different ; but I said it then and I stand to it now --- it was a sockdologer. And moreover, besides, it landed Tom Sawyer. He could n't say a word. He had that stunned look of a person that 's been shot in the back with a kag of nails. All he said was, as for people like me and Jim, he 'd just as soon have intellectual intercourse with a catfish. But anybody can say that --- and I notice they always do, when somebody has fetched them a lifter. Tom Sawyer was tired of that end of the subject.

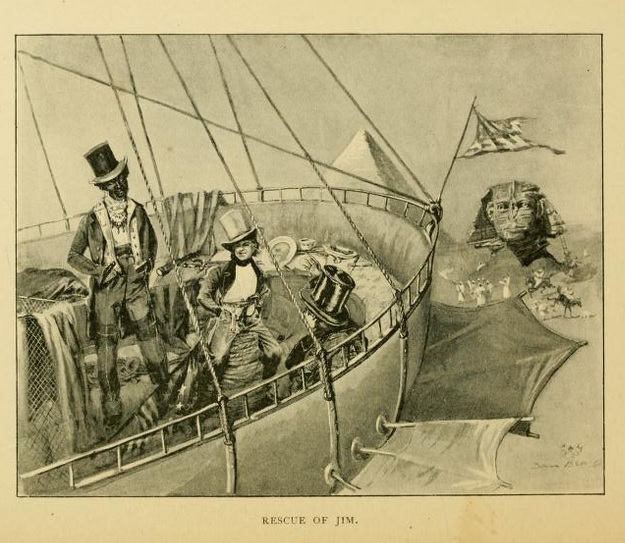

We did n't see half there was to see in Cairo, because Tom was in such a sweat to hunt out places that was celebrated in history ...

We hunted a long time for the house where the boy lived that learned the cadi how to try the case of the old olives and the new ones. Tom said it was out of the Arabian Nights and he would tell me and Jim about it when he got time. Well, we hunted and hunted till I was ready to drop, and I wanted Tom to give it up and come next day and git somebody that knowed the town and could talk Missourian and could go straight to the place ; but no, he wanted to find it himself, and nothing else would answer. So on we went.

Then at last the remarkablest thing happened I ever see. The house was gone --- gone hundreds of years ago --- every last rag of it gone but just one mud brick. Now a person would n't ever believe that a backwoods Missouri boy that had n't ever been in that town before could go and hunt that place over and find that brick, but Tom Sawyer done it. I know he done it, because I see him do it. I was right by his very side at the time, and see him see the brick and see him reconnize it. Well, I says to myself, how does he do it ? is it knowledge, or is it instink ?

Now there 's the facts, just as they happened : let everybody explain it their own way. I 've ciphered over it a good deal, and it 's my opinion that some of it is knowledge but the main bulk of it is instink. The reason is this. Tom put the brick in his pocket to give to a museum with his name on it and the facts when he went home, and I slipped it out and put another brick considerable like it in its place, and he did n't know the difference --- but there was a difference, you see.

I think that settles it --- it 's mostly instink, not knowledge. Instink tells him where the exact place is for the brick to be in, and so he reconnizes it by the place it 's in, not by the look of the brick. If it was knowledge, not instink, he would know the brick again by the look of it the next time he seen it --- which he did n't. So it shows that for all the brag you hear about knowledge being such a wonderful thing, instink is worth forty of it for real unerringness. Jim says the same.