Knowledge, as everyone knows, is power, and

therefore accessibility of information is ultimately

a political issue. Even in the case of abstruse

scholarly material, ease of access has been

a key issue throughout history. The Early Modern

"scientific revolution" was succesful in part because

it was international, and it was international not

only because of the printing press but also

because of the internationally circulated

journals and transactions of the new learned

societies. By the 1880s, however, neither these

publications nor the open-access research

libraries which stored their back numbers

could meet the demands of the new era ...

A WIDER USE FOR THE LIBRARIES OF

SCIENTIFIC SOCIETIES.

Unsigned editorial.

Science 4, 334 (1884).

The author's words are in

bold.

TO those who are obliged to use the libraries

of our smaller colleges, it is often a source of

vexation to find that the books one is referred

to are wanting. The resources of the colleges

are limited, and the amount of money which can

be expended for the purchase of new books

small, and that small amount often devoted,

according to the wishes of the donor, to the

class of books least needed. A case in point

occurred lately, where a college professor of

mathematics was asked to write a short account

of the life of Todhunter ; and he felt obliged

to say that he would be glad to undertake the

article, but could not before he had visited the

libraries of either New York or Boston, which

he hoped to be able to do during his next

vacation.

This constant lacking of just the books one

needs for his work is most hampering. It is

not the

Century, or the

Harper, or the latest

novel, or the new book of travel, which

cannot be had (these find their way into all the

odd corners), but it is the specialist's books,

a volume of the transactions of some learned

society, a scientific journal, or the modern

treatises on thermo-dynamics, on electricity,

or on biology, which are needed, and which

can be found only in a very few of our libraries

in the necessary profusion.

A few such libraries have now been collected

by our older scientific societies and our larger

colleges. The books of the college libraries

are for a specific purpose, and find abundant

use at the hands of the students and professors.

With the societies the matter stands differently.

It cannot be denied that one of the original

objects of the establishment of these societies

was, that, by the publication of their own

"Proceedings," they might, by exchange, gather

a collection of books which could not, in the

then comparatively poor state of the country,

be gathered in any other way, and which were

to be for the use of the members, and such

favored friends as they might designate.

It has so happened that these societies were

established by the small knots of scientific

men gathered about our larger colleges. These

colleges have developed, and their libraries

have grown more and more valuable ; so that

the professors no longer find it necessary to

go to their academy for books. At the same

time the machinery of their long-established

organization has grown more effective ; and,

while many of the members no longer need

their society collection of books, the number

and value of those added to the shelves each

year are constantly increasing. The result

is, that in some of our larger cities there

are accumulating very considerable libraries

of special works which are scarcely used, as

they are duplicated at some neighboring college

about which those employing such books

live.

It is, of course, with regret that one enters

such a library, if library it may be called, and

sees the new books which are not called for by

the former clientage of the collection, but

which would eagerly be asked for if the circle

of favored outsiders were widened so as to

include all properly vouched-for persons who

might live within one, two, or three hundred

miles, or even more, and who would be willing

to pay a small annual fee to defray the expense

of sending books to them by mail or express,

and for the extra wear, and danger of loss. It

is true that such books as could not be readily

replaced in case of loss would necessarily be

retained from such a wide-spread circulation ;

but these would be only the older volumes of

the various series, and such books as are very

generally kept from such extra risks.

The expense of mailing would be considerable

; it would average, on volumes of the size

of a bound volume of the

American Journal

of Science, about sixteen cents each way.

To this must be added the cost of handling, and

some slight charge for the privilege of use.

Altogether, the expense of taking out, say,

forty books of this class in the course of the

year would be in the neighborhood of ten to

fifteen dollars, --- a charge which could be

reduced very materially by sending for the

books a number at a time, so that they might

be forwarded to advantage by express ; the

amount named above being the maximum if

each book were mailed separately.

That the expense of using a library through

the mails would mount up very rapidly is

evident ; but the facts remain, that there are large

libraries of books solely on matters of interest

to scientific men, and of vital interest to such

men, and that these libraries exist in

communities where by duplication they no longer

have their former use. It is highly desirable

that the books should be put to use ; and their

owners would probably be glad to arrange

some plan by which the scheme of extending

the circulation through the mails could be made

practicable. It would be of great advantage

in perfecting plans, if those who might be

benefited would come forward and state their

position.

The editorial provoked a number of

letters. Those which Science

published

were all positive:

Science 4, 368 (1884)

I noticed in the last number of Science a proposition

to render the libraries of the various scientific

societies more useful by circulating the books

somewhat by mail, among persons located in small towns.

If those having charge of those libraries knew what

a blessed boon such an arrangement would be to a

man situated as I have been for a few years, I am

sure they would heartily second the proposition.

Colleges are often located in small towns, and are very

poorly supplied with the means for scientific study

or investigation. Professors in such institutions

would be delighted with any arrangement, not

involving very great expense, which would give them

access in any way during term-time to a good

scientific library. Would not some such arrangement as

this be a wise one? --- Require a person wishing for

the privilege of taking books from the library to give

bond for a sum sufficient to meet all possible liabilities,

and charge to his account all the actual expenses

incident to packing and mailing or expressing books

to him, and also any books not returned. Charge

him, also, a small annual fee for the use of the books.

In that case, he would pay only the actual expenses,

and for the use of the books.

I earnestly hope our scientific societies may consider

this question, and give to those of us who are

isolated from the rest of the world, in small colleges

and small towns, the benefit of the wealth of learning

idly hoarded up in their libraries.

W. Z. Bennett.

Wooster, Wayne county, O.,

Oct. 7.

Bennet taught scientific subjects at the

University (now College) of

Wooster in Ohio.

Science 4, 396 (1884)

In Science for Oct. 3, your editorial calls attention

to the need of making scientific libraries more widely

useful. Perhaps some of your readers will be glad to

know the liberal policy of the

Boston Society of Natural History.

The society is willing to send such books

as can be replaced, to students in any part of the country,

at their expense of course ; asking from strangers

a deposit of twice the market-value of the books so

sent, as a guaranty against loss. This is an example

which may well be followed by all special libraries.

Edward Burgess,

librarian.

Boston, Oct. 17.

Burgess was a typical Nineteenth Century

American intellectual with wide-ranging interests.

Although employed as a biology instructor at Harvard,

he is best remembered for designing the yacht Puritan

,

which won the America's Cup in 1885.

The Boston Society of Natural History is today the

Museum of Science above

the Charles River between Boston and Cambridge. In its current incarnation,

the Museum of Science is aimed chiefly at the general public, and

especially at children; in its mission statement it defines itself

as "an informal learning institution to help the formal preK-12

education system". This is true of most "science museums"

in the Western world. No one would wish to deny the importance

of the work of such science museums; nevertheless, they

provide an example of the contingent nature of history.

In our society, "serious" scientific research is conducted at universities,

at a few elite undergraduate colleges, at government or industrial laboratories,

and at small number of dedicated "research institutes". Other societies

have done things differently: original research has at various times been pursued

chiefly in monasteries, in parsonages, on the estates of aristocrats,

even in the porticoes of Athenian public buildings. Very small changes in

history could have seen museums, public libraries, and zoos become

dominant engines of scientific progress during the 1900s, with colleges and universities

relegated to a purely instructional role. The latter half of that process is

unfortunately taking place in the Twenty-First Century, but with non-academic

institutions failing to take up the torch dropped by academia.

Edward Burgess in 1887

Science 4, 413 (1884)

Your remarks in Science (iv. 335-338) on a wider

use for the libraries of scientific societies, give me

occasion to mention at least two societies which

make such use of their libraries. I think you would

do a service by collating a list of such societies, and

making a statement of their rules for the loan of

books. A brief standing notice, or one occasionally

inserted, would be of service to your readers.

Certainly the societies not deriving a revenue from

these loans should not be expected to advertise at

their own expense.

The constitution of the American Association for

the Advancement of Science provides that all books

and pamphlets received by the association shall be

catalogued, and that members may be allowed to call

for such books and pamphlets to be delivered to them

at their own expense ; but as yet the books are not

available, as the catalogue has not been made.

The

Cambridge Entomological Club allows subscribers to

Psyche the use of its library under certain restrictions,

--- a library containing about a thousand titles.

On the other hand, the

American Entomological Society provides that "no

books presented to the society

shall be loaned from the hall under any pretence or

for any purpose whatsoever."

The publishers of the

Revue et magasin de zoologie,

at Paris, conducted for many years a circulating

library amongst the subscribers to the magazine, and

reported that they had never sustained the loss of a

single volume. Will not other societies or periodicals

copy these practices ?

B. Pickman Mann.

Washington, D.C., Oct. 21.

Mann, son of the famous Horace, was another Harvard-trained biologist.

He founded the Cambridge

Entomolgical Club before entering government service with the Department of

Agriculture, and thus stood at the exact cross-road of scientific

history where "amateurism" and "professionalism" diverged

in the late 1800s.

Pickman Mann thirty years later (from the

Washington Times, 1914 November 12, illustrating an

article about Mann's efforts to improve the legal status of children

born to unwed mothers.)

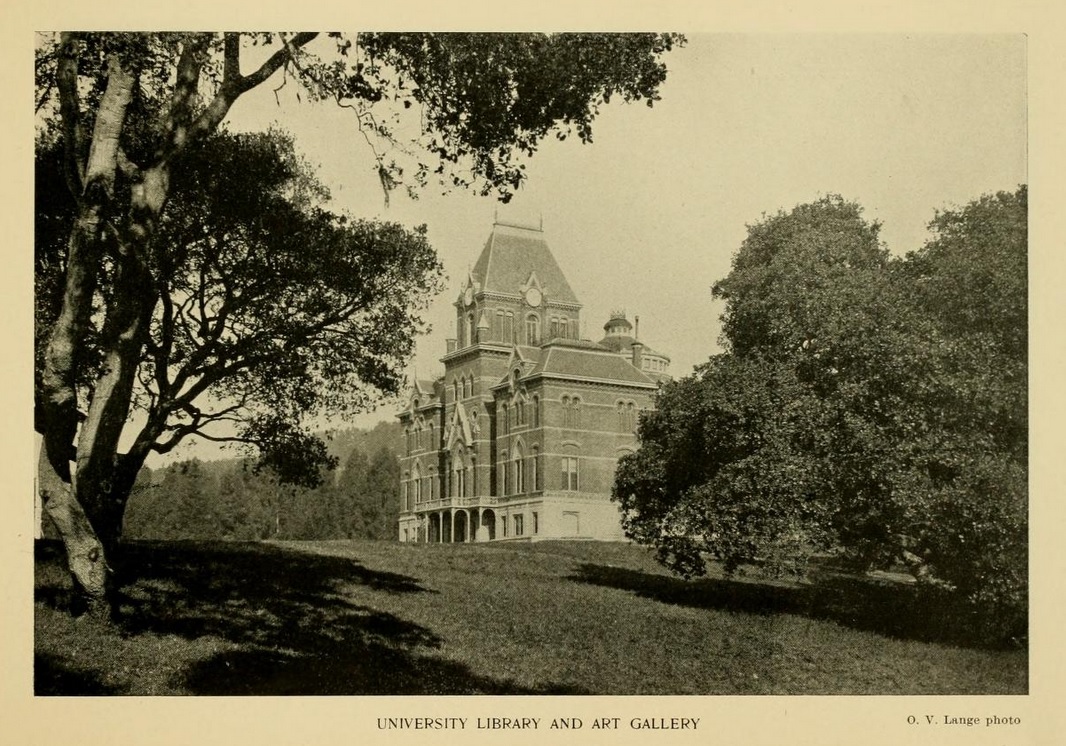

"Interlibrary loan" was an idea whose time had almost come, and by 1894

it was a reality in California through the efforts of Berkeley's

Joseph C. Rowell (comically known to

Wikipedia as "U. L. Rowell" from a misunderstanding of

the abbreviation for his job

title "University Librarian"). In the Twentieth Century the

growth of interlibrary loan programmes was slow (probably because falling

publication costs, philanthropic bequests, and government funding

made it possible for small institutions to greatly expand their own holdings)

but inexorable, and by the heyday of Big Education in the 1960s

practically any book not classified as "rare" could be borrowed by any

scholar in the Western world.

Ironically, just as online databases, especially

OCLC WorldCat, moved interlibrary loan out of the hands of librarians

and into those of users, the whole system began to seem outdated. A century

after Rowell the demand is not for physical copies of books but for their digitised content,

and the issues of fairness, control, and above all "Who will pay?" remain

as central and as controversial as they were in 1884.