First, I wish to reiterate the comment Jeffrey Cohen made at In the Middle

on the indescribability of last weekend’s conference. Secondly, this

post tries not to fill in the blanks of the “AVMEO experience” as much

as add another layer to the rich sediment surrounding the event. (Here I point to the brisk conversations happening now: posts by Eileen Joy at ITM; Jonathan Gil Harris and Nedda Mehdizadeh,

my conference cohorts, at this blog; and the posts and threads to come,

I’m sure.) As audio feeds become available over the next few weeks,

those of you who were unable to join us over the nutritious, albeit

rigorous and theoretically engaging, weekend will be able to participate

in these conversations as well. Please do.

Although I don’t have any pressing Iowan engagements like Jeffrey, my words are nevertheless slow

in coming. And despite that this conference, to paraphrase Julia

Reinhard Lupton on Saturday night, feels like a “commencement” or an

“initiation,” I’m still slow out of the gate.

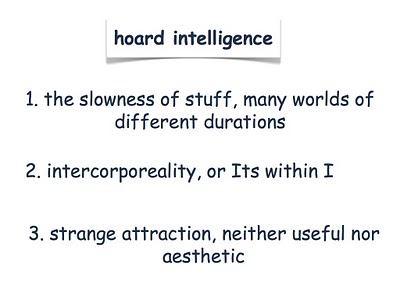

But slowness,

I know, is all right. The conference couldn’t have come at a more

accelerated time in my doctoral career. I’m deep in my dissertation

topic of “ecomaterialism:” exploring early modern landscapes (or any –scape) as vibrant (Bennett), living,

actor-networks (Latour/Serres) of (non)human desires and assemblages

(Deleuze). Sometimes I accelerate too fast – as this last sentence make

clear. How do we (in the delicate sense of the “we”) compose with the

world (in all senses of the word “compose”)? Ecomatter is my mind, and

ecocriticism is a vast place to inhabit. And the ontological questions I

ask – I need to ask – are beginning to get more “speculative.” Eileen,

for example, used Timothy Morton’s work to describe the binary “bind”

between human and nonhuman, inside and outside. According to Morton’s

“dark ecology” we can’t cancel or preserve this binary, just accept it,

and should furthermore delve deeper into it than deep ecology allows.

His “melancholic ethics” means “loving the thing as thing,” even if it

means staying in the “slime” or “this poisoned ground.”[i]

How can/do things relate? Graham Harman was the other absent

interlocutor for many of us at the conference. Eileen brought up his

object-oriented-ontology in her talk as well – never really touching,

objects and their relationships recede from us, relating only to one

another in the presence of a third (the vicar) in “vicarious causation.”[ii] Questions abound (rightfully so; see Gil’s post) and complications

emerge. The “ethics of interdependence” that Eileen ardently spoke of

feels suddenly necessary. Ethics is, in Eileen’s words, “a slowing

down,” a welcoming of the other, an addition of beauty. We should listen

to the countless inhuman actors in the world, start forming alliances

for more sentience (and keep doing it!), and make room for hospitality

and its possibilities. (Listen to Peggy McCracken’s captivating talk

regarding the host as well.) To paraphrase two (or four?) of Eileen’s

alerts, you are here and there are relations. Hello, everything – we’re co-implicated.

So let’s slow down. I want to pick up on Eileen’s idea of the humanist as a “slow recording device,” a being involved in a world of complication

(relationships and theories of relationality, of which Morton and

Harman are only two, to be sure) who also describes a world of co-implication, of sentience, becomings, and desires shared between actants – whether inanimate or animate. What happens when we slow down, when we take the time to take these ethical steps seriously?

I

will try to trace a solid example. (“Track”, actually, might be more

useful when talking about steps left behind for us, borrowing from

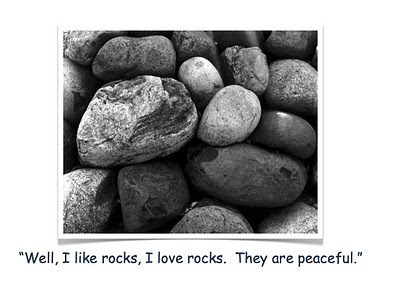

Julian Yates’s woolly speech.) Not surprisingly, I turn to an object –

no, not the speeding beach ball hurled at Jeffrey’s head. I’m speaking

rather of the stone I retrieved from Valerie Allen’s lapidary grab bag

during her talk on “Mineral Virtue.” There is

a surprise to this object, after all. Valerie’s lecture, while

addressing in its content what Jane Bennett calls “thing-power,” also

brought up issues of material agency in its very method. The randomness

of the bag – why did I receive an alluring

light blue rock that now cohabits my apartment? – underscores what

Julian elsewhere has called “agentive drift.” For Julian, drift

represents agency itself: when/how one becomes an actor, what these

varying actors will become across their endlessly variable networks,

into what aleatory directions they might go, “a dispersed or distributed

process in which we participate rather than as a property which we are

said to own.”[iii] This process importantly produces. Think of Carla Nappi’s consideration of “things as

motion” in her discussion of how things undergo “cottonification.”

Becoming light-blue stone, perhaps, is the slowest thing imaginable. But

drifting with the random stone connected me at that moment, and

connects me still, to others with their mutifarious rocks. This form of

audience participation or petrification?) shores up one of Julia’s points neatly: how the proximity of assembly and assemblage relates the essential (inter)dependence between persons and things (once again). Was not the conference, at its heart, as event, this very thing?

But

wait! Slow down. There’s an additional thing out of the bag (at least

for now). I’m speaking about the rock as part of a “domestic ecology”

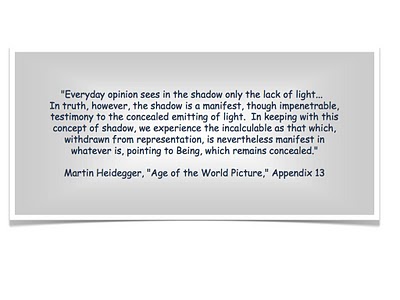

(Julia). Or, should I say, I’m speaking to it? Or, should I say, it’s speaking to me? As I write this, it

is “over there” on my desk. For some critics, minding place poses the

very problem of contact and how things relate. Yet in my conversation

with the stone – I use “conversation” deliberately; stressing the con- (with) and the verse (to turn) – my very writing (right now!) is an alliance, a thing that exists because

it is a relation and produces relations (Latour). These continuous

connections – stone, keyboard, kiwi, you the reader – shouldn’t

primarily lead to the complications of causality, origin, and distance,

for they fundamentally take us to the weird joys, strange horizons, and

new modes of being that co-implicated assemblages afford. And they

should at least drift us away from the bullying terms of

anthropocentrism and anthropomorphism that (too often) mire

ecocriticism. The speaking-writing-stone-subject-object-that-I-am does

not dissolve the human/nonhuman border in an act of prosopopoeia, but in

fact highlights this border’s ontological nonexistence altogether. In

turn, an “ethics of interdependence” involves the “humanist recording

device” tracing these tracks of (non)human connections all the while

making new ones slowly across time. Ecopoesis would be one example. What else?

Like

speaking stones. Like stooping to stone. I think we have a lot to learn

from the zany ethics of someone like John Muir, the nineteenth-century

Scottish naturalist known for, in addition to his tireless

preservationism, his eccentric habits and perambulations in the Yosemite

Valley. Muir, in other words, was a consummate drifter;

he drifted with the world. Coincidentally, he was ridiculed for the

strange habit of “stone sermons,” moments when he dialoged with living

rock (his belief) and recorded the lessons learned. Take his

methodology, for instance:

“I

drifted about from rock to rock, from stream to stream, from grove to

grove. Where night found me, there I camped. When I discovered a new

plant, I sat down beside it for a minute or a day, to make its

acquaintance and try to hear what it had to say. When I came to

moraines, or ice-scratches upon the rocks, I traced them, learning what I

could of the glacier that made them. I asked the boulders I met whence

they came and whither they were going. I followed [...]”[iv]

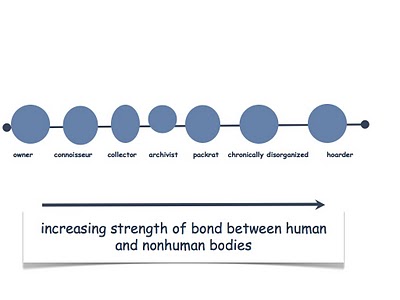

Muir

stoops to listen, not to conquer. He beautifully encapsulates what Jane

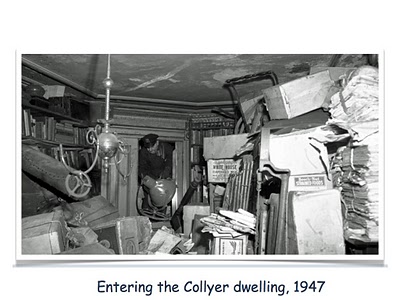

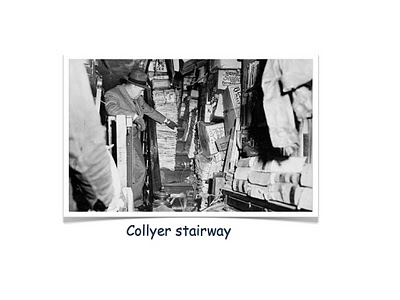

invoked in her keynote lecture about hoarders: “Hearing the call of

things.” As such, Muir risks the same pathologization that hoarders

incur for their “preternatural vital materialism.” As I’ve been

suggesting in this response, an ethics of interdependence is just Muir’s

method: an ethics attuned to the voices of things (like rocks) spoken to (“I asked”) and heard from

(“to hear what it had to say”). The humanist recording device

translates these voices into a body of work, thereby inventing an

assemblage of (non)human traces. By drifting “from

rock to rock” with a living landscape, by following the boulders’

physical tracks (“whence they came and whither they were going”) Muir’s

“traced” (or written) experiences emerge. Nevertheless, although

“hearing the call of things” for Muir is a powerful moment of

interdependence, Jane reminded us that this “call” is not one devoid of

complications. Kellie Roberston, in a sparkling lecture on Chaucer as

“man-mineral assemblage” brought to mind “dead” rocks as well. Karl

Steel’s and Sharon Kinoshita’s animal lectures put pressure on

animal/human boundaries but also exposed the fears that perpetuate them:

the precarious “living lupine home” (Karl), the “taxonomic imagination”

of Christianity versus Islam (Sharon). In others words, things are complicated. Ultimately, what is crucial to remember is that there are relations, and that hearing the calls of animals, vegetables, and minerals – hello, everything – leads us into places unknown, both dark and beautiful, and into co-implicated conversations, Muir-like, that we “follow” and “follow” and “follow” some more.

[Thank you

to the panelists, speakers, and participants who made AVMEO such a

success. Special thanks to my vibrant committee co-members: Jeffrey

Cohen, Jonathan Gil Harris, and Nedda Mehdizadeh.]

[i] Ecology without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007).

[ii] See, for instance, “Time, Space, Essence, and Eidos: A New Theory of Causation” in Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy 6:1 (2010).

[iii] See “Towards a Theory of Agentive Drift; Or, A Particular Fondness for Oranges circa 1597” in parallax 8:1 (2002).

[iv] John of the Mountains: The Unpublished Journals of John Muir (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1979) 69.