|

Conservation of the Urban Fabric

Walled City of Lahore, Pakistan

Zachary M. Kron

INTRODUCTION

This case study on urban development in

the province of Punjab focuses on the Pakistan Environmental

Planning and Architectural Consultant's efforts to create and

implement an urban conservation plan for the walled city of Lahore

in the early 1980's. With a population of four million in 1992,1 this old

quarter of Lahore is under tremendous pressure from commercial

and industrial interests, which as yet have little regard for

the historic nature of the city. In addition to these active

menaces, the city is struggling to integrate new municipal services

into its existent tissue without obscuring its visual character.

Although few interventions have actually been achieved, several

higher profile "pilot projects" have been carried out

in an effort to raise public awareness of the conservation plan.

CONTEXT

Physical

Lahore is the capital of the province

of Punjab, the most fertile area of Pakistan and chief producer

of agricultural products for the country. The city is generally

arid, except for two months of hot, humid monsoons, and receives

less than 20 inches of rain during the course of a year.

Historical

The earliest credible records of

the city date its establishment to around 1050 AD, and show that

its existence is due to placement along the major trade route

through Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent. The city was

regularly marred by invasion, pillage, and destruction (due to

its lack of geographical defenses and general overexposure) until

1525 when it was sacked and then settled by the Mogul emperor

Babur. Sixty years later it became the capital of the Mogul Empire

under Akbar and in 1605 the fort and city walls were expanded

to the present day dimensions. From the mid-18th century until

British colonial times, there was a fairly lawless period in

which most of the Mogul Palaces (havelis) were razed,

marking a "decrease in social discipline towards the built

environment that has continued unabattingly till today."2 Much of the

walled fortification of the city was destroyed following the

British annexation of the region in 1849, as both a defensive

measure to allow the colonists to better control the populous,

and as a commercial enterprise in resale of the brick for new

projects. In 1864 many sections of the wall had been rebuilt.

Major physical contributions of the British to the old city consisted

of piped water and well systems established just outside the

former walls. The building of the railroad and a station well

outside of the old city set the stage for later expansion.3

Social and Economic

A new wave of destruction washed

over the city in 1947 following the partition of British Colonial

India into the Hindu majority nation of India and the Islamic

Republic of Pakistan. The resulting inter-communal strife destroyed

wide areas of the urban fabric, some of which was repaired by

the 1952 Punjab Development of Damaged Areas Act. Many of the

arriving Muslim families from India moved into the emigrating

Hindu residences, although the lower land values of the old city

further established the concentration of lower income groups

in the city center, with wealthier families residing outside.

In the 1950's an organization called the Lahore Improvement Trust

attempted to instate a plan for commercial development in the

old city, but these efforts were largely without effect.4 Between the

early 1970's and '80's, 29% of the old city population moved

out.

The space left by emigrants from the old

city has largely been filled by commercial interests, mostly

small scale manufacturers and wholesalers, many of whom have

national and international clients and do not serve the local

community. The advantages for commercial interests are the readily

available cheap labor force among the urban poor, as well as

relative anonymity, which facilitates the evasion of most national

and local taxation. Advantages for speculative developers lie

in the absence of enforcement of building regulations, as well

as in cheap plots. The resulting commercial encroachment demonstrates

a pattern of abuse of building stock through inappropriate re-use

of structures intended for small scale (cottage) industry and

residential use, as well as destruction of older buildings replaced

with quickly erected, lower quality structures.

To the northwest, in the city of Peshawar,

and to the east, in Delhi, one can find buildings related in

form and age to those in Lahore, although in Peshawar the residential

construction is primarily of wood. Although Peshawar was controlled

by the Moguls and populated with mosques and gardens as Lahore

was during the 16th and 17th centuries, little of it remains

to be seen. Peshawar also has it's share of British construction,

(including the renovated Mahabat Khan Mosque built under Shah

Jehan but largely redone in 1898), and many of the existing residential

buildings date from the late 19th century. Like Lahore, the small

grain of the urban fabric left intact can be attributed to the

growth of the city within a walled fortification.

THE PROJECT

Significance of the Walled City

The walled city of Lahore is the

product of the cultural influences of at least three major empires

in the subcontinent of India: the Mogul Empire, the British colonial

presence, and the modern nation-state of Pakistan. As a result

of its position along a major trade route, it has also been influenced

by many other, less dominant cultures, such as Afghanistan and

China. Unlike Peshawar, which has lost much of it's larger scaled

architectural past, and Islamabad, which can only boast Modern

Monumental architecture of some merit, Lahore contains some of

the best of all the empires which have touched it, as well as

smaller scale vernacular architecture.

In addition to this object value, the walled

city plays a central role in the daily functioning of Lahore.

It remains a bustling center of commerce and represents the "living

culture" of the city, an enduring continuation of and evolution

from a much older way of life. As the city contains many heterogeneous

physical attributes, the activities of the walled city include

all aspects of urban life: residential, manufacturing, retail,

educational, religious, and civic.

CONSERVATION PHILOSOPHY

The Lahore Development Authority's Conservation

Plan for the Walled City of Lahore is a series of recommendations

concerning the physical decay of historic structures in the city,

the "visual clutter" of newer structures and

infrastructure, and the encroachment of various unregulated elements

on the city's fabric. This program of conservation, headed by

Pakistan Environmental Planning and Architectural Consultants

Ltd. (PEPAC) is actually the expansion of a project begun in

1979, the "Lahore Urban Development and Traffic Study"

(LUDTS). This study, undertaken by the Lahore Development Authority

(LDA) and funded by the World Bank, identified four areas for

improvement. "1. Urban planning activities, leading to

the production of a structure plan to provide a framework for

action program within Lahore; 2. Neighborhood upgrading and urban

expansion projects, to provide substantial improvements in living

conditions for lower income groups; 3. Improvement of traffic

conditions in congested parts of the street system of central

Lahore: and 4. Improvements to living conditions within the walled

city by improving environmental sanitation and providing social

support program."5

Part of LUDTS' findings identified the

precarious position of the physical fabric of the city. The report

suggested (among other things) that any development and upgrading

program that the city initiated should include measures "to

protect national and regional cultural heritage," and to

that end it recommended the development of a conservation plan.

The World Bank made the creation of a plan a condition of the

first loans to be issued to Lahore.

The study identifies some 1,400 buildings

within the city as having high architectural or historical value

and presents a series of conservation proposals. These recommendations

include both conservation steps for the buildings themselves,

as well as social and economic programs to halt the causes of

their degradation. In general the study suggested the following:

1. Strategic policies and actions to be taken outside the walled

city.

2. Planning activities and studies for both the central area

and the walled city.

3. Institutional development including the full utilization of

existing resources reinforced with an active training program,

and the application of the legislative resources that already

exist.

4. Urban management and controls to include production of a "Manual

for Conservation and Building Renewal" and improved maintenance

practices.

5. Traffic improvement and management program.

6. Upgrading and enhancing the physical fabric and the urban

environment through upgrading the building stock . . . and through

upgrading urban services.

7. Redevelopment with concern for conformity with the scale,

height, densities and building typologies traditionally characteristic

of the walled city to be demonstrated through projects undertaken

by public authorities on state land and through regulated private

sector activity.

8. Conservation of individual listed special premises or elements.6

CONSERVATION PROGRAM INTERVENTIONS

While the statement above outlines a general

policy approach to the conservation effort, several pilot projects

have been more specifically outlined and a handful have been

implemented and funded by the World Bank through the Punjab Urban

Development Project. The buildings are, in most cases, structures

dating from early British colonial times, both residential and

commercial, and more monumental structures from the Mogul Empire,

although action has only been taken on government owned buildings.

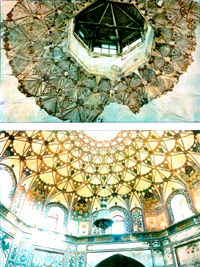

One pilot project that has come directly

out of this effort is the restoration of the Wazir Khan Hammam

(bath house), built in 1638. The bath, which suffered mostly

surface damage to the fresco work, is now being re-used as a

tourist center with some facilities for computer education for

women. While the structure itself was not in any particular risk

of irreversible decay, this hamam is a particularly important

site to the Development Authority because it is located on a

popular entrance point for tourists coming to the city. For visitors

it is the first logical stopping point on a walk that goes from

the impressive Delhi Gate (Image 6) past the Wazir Khan Mosque

and the Choona Mandi Haveli Complex to end at the Lahore Fort.

This route is also well traveled by locals going to the wholesale

cloth and dry goods markets. It seems that the choice of aiming

the rather limited resources of the program at this project is

an attempt to heighten the community interest in the conservation

effort, rather than directly addressing sites with more desperate

conservation needs.

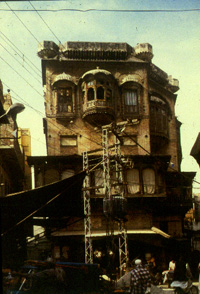

Additionally, there are several proposals

to deal with the conservation of areas surrounding historic monuments.

Of particular concern is the area around the Mori Gate, which

stands next to the well preserved UNESCO site of the Lahore Fort,

and lies between the Fort and the Delhi Gate, immediately adjacent

to the newly conserved and re-used Choona Mandi Haveli Complex.

While the Fort itself is a vigorously monitored and controlled

site, the area immediately surrounding it is "visually cluttered,"

to say the least. One exits the Fort to be confronted by a mass

of electrical cables, transformers, and half a dozen steel recycling

operations.

PEPAC's proposal involves the relocation

of the steel traders (whom it claims are operating illegally)

to a more suitable location and repopulating the area with a

mixture of commercial and residential uses. The area itself does

not contain artifacts of particular merit, but is amid a concentration

of other historic elements.

In their statement of policy and issues,

PEPAC refers to the exemplary conservation work done at the Choona

Mandi Haveli Complex, and to its re-use as a degree college for

women. While this is not a PEPAC project, it is identified as

a model of the work they wish to see happening in the city, and

claim that the project "came out of the conservation effort"

that they are creating.7

While it is unclear from the literature

who in fact has implemented the particular conservation of the

Haveli Complex or what the connection is to the PEPAC

effort, it is clear a particular region of the city has been

identified as a primary site for conservation efforts. It seems

sensible to concentrate on blocks of the city as specific focus

areas for limited resources and as showpieces to use to solicit

further funding, but it is curious that this is not stated as

a strategy in the group's policy statements.

In addition to these concentrated areas

of restoration, the main gates to the city have been chosen as

pilot projects, several of which have already undergone restoration

work. In order to determine how the restored gates should appear,

PEPAC searched for clues not only in their existing condition,

but also in historical documentation of the gates from the pre-colonial

period. In particular, a wealth of information was found in the

numerous renderings by French and British explorers from the

17th century who made paintings, drawings and etchings of the

sites. After identifying the site and determining the changes

that are to occur in the area, the site was "vacated of

encroachers," who currently occupy the niches, hollows and

shelters provided by the wall. Several of the gates have now

been restored to their pre-colonial state, but the work has recently

been halted due to the cessation of World Bank funding.

AUTHOR'S CONCLUSION

The example of the gates highlights several

difficulties faced by PEPAC in the implementation of their conservation

project. First, and perhaps most minor, is the fidelity to the

historical record that the conservators wish to maintain. Although

the accuracy of the sketches can be verified by different views

supplied by different artists, it is not necessarily appropriate

to restore the gates to the condition they were in during that

particular era, especially at the expense of people who may have

some claim to residency in portions of the site.

A more important criticism is that the

definition of "encroacher" is inadequate. The Prime

Minister has attempted to implement a policy to allot property

rights to squatters as a way of instilling greater commitment

in them to properly maintain the areas they occupy.8 However,

PEPAC does not qualify the distinction between squatters, "encroachers,"

and residents. Furthermore, 20 million rupees that have been

earmarked by the Punjab Urban Redevelopment Project for residents

to use for the improvement of their own property was not dispersed

due to the inability of the organization to identify legal residents.9

With no clear definition of who is a resident

it will continue to be impossible to make a generalized policy.

The total absence of legal enforcement of property rights further

undermines any sense of ownership. An example is the rapacious

acts of the speculative developer who buys a building and then

digs a second basement, which effectively collapses the neighboring

buildings. The owner, without legal recourse that would provide

any results, is left with no choice but to sell their ruined

plot to the developer, who then erects a cheap, commercial building.10

This dilemma underscores a central conflict

in the policy of conservation enacted by PEPAC. On the one hand

is the attempt to instate a series of guidelines and regulations

which the residents of the city must follow, and on the other

hand is the attempt to encourage a sense of ownership, pride

and respect among residents for the architecture. The first effectively

removes or reduces the choices of the resident in determining

the form of their surroundings and relies upon a policy of rule

enforcement. The second relies upon the living culture of a place

to perpetuate the existing physical culture, although allowing

for the changing needs of the people. Unless policy is made concerning

ownership and enforcement, these two approaches, which are not

necessarily in conflict, will not act in accord, and will each

remain ineffectual.

It is interesting to note that the areas

where the PEPAC conservation effort has been most effective is

in exclusively government owned properties: schools, municipal

dispensaries, monuments and civic buildings, as well as the homes

of police officials.11

In the case of the other projects that

have been implemented, PEPAC may be criticized for prematurely

starting restoration work before active degradation is stopped,

or even slowed. The resurfacing of the Wazir Khan Hamam and work

on the area between the Delhi and Mori Gate are a prime example

of this, a fairly stable area is being conserved while nearby

buildings are being razed for newer construction or crumbling

through neglect. (Image 9) However, given the dependency

of virtually the entire conservation effort on World Bank funding,

it must be a priority for the group to create a visible, finished

grouping of conserved buildings in order to solicit further funding.

This example of trying to raise consciousness

before actually acting to stop degradation is appropriate for

any conservation project undertaken in Lahore. From the inception

of the current conservation plan, the impetus for preservation

has come from outside the city walls and has been hindered by

a discrepancy between what is said in meeting rooms and what

happens in reality. In the absence of a fairly oppressive and

well-funded preservation enforcement program, conservation in

the walled city will not be effective without the support and

active interest from the people who inhabit it.

Endnotes

1. John King, and John St. Vincent, Lonely

Planet Travel Survival Kit: Pakistan, 4th Edition (Lonely

Planet Publications, 1993), p. 191.

2. PEPAC

3. Pakistan Environmental Planning and

Architectural Consultants Ltd, Lahore Development Authority:

Conservation Plan for the Walled City of Lahore, Final Report,

vol. 1, Plan Proposals (1986), p. 7.

4. Reza H. Ali, "Urban Conservation

in Pakistan: a Case Study of the Walled City of Lahore,"

Architectural and Urban Conservation in the Islamic World,

Papers in Progress, vol. 1 (Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture,

1990), p. 79.

5. Lahore Development Authority /Metropolitan

Planning Wing, with the World Bank/IDA, "Lahore Urban Development

and Traffic Study," Final Report/vol. 4, Walled City Upgrading

Study (August 1980), preface.

6. Ali, "Urban Conservation in Pakistan,"

p. 87.

7. Pakistan Environmental Planning and

Architectural Consultants Ltd, Issues and Policies: Conservation

of the Walled City of Lahore, (Metropolitan Planning Section

Lahore Development Authority, 1996), point 5.

8. Pakistan Environmental Planning and

Architectural Consultants Ltd, Lahore Development Authority,

Conservation Plan for the Walled City of Lahore, Final Report,

vol. 1, Plan Proposals. (1986), p. 180.

9. Pakistan Environmental Planning and

Architectural Consultants Ltd, Lecture given on the Walled City

of Lahore Conservation Project (July 25, 1998).

10. (Sajjad Kausar)

11. PEPAC lecture (25 July 1998).

Bibliography

Ali, Reza H. "Urban Conservation in

Pakistan: a case study of the Walled City of Lahore." Architectural

and Urban Conservation in the Islamic World. Papers in Progress.

vol. 1. Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 1990.

Background Paper: Lahore Pakistan. Prepared

for Design for Islamic Societies Studio, MIT Department of Architecture

and Planning, 1992.

King, John and St. Vincent, John. Lonely

Planet Travel Survival Kit: Pakistan, 4th Edition. Lonely

Planet Publications, 1993.

Lahore Development Authority /Metropolitan

Planning Wing, with the World Bank/IDA. "Lahore Urban Development

and Traffic Study," Final Report/vol. 4. Walled City Upgrading

Study. August 1980.

Nadiem, Ihsan H. Lahore: A Glorious

Heritage. Lahore: Sang-e-meel Publications, 1996.

Pakistan Environmental Planning and Architectural

Consultants Ltd. Lecture given on the Walled City of Lahore Conservation

Project. July 25, 1998.

Pakistan Environmental Planning and Architectural

Consultants Ltd. Monographs on the Walled City of Lahore.

Pakistan Environmental Planning and Architectural

Consultants Ltd. Lahore Development Authority. Conservation

Plan for the Walled City of Lahore. Final Report. vol. 1.

Plan Proposals. 1986.

Pakistan Environmental Planning and Architectural

Consultants Ltd. Issues and Policies: Conservation of the

Walled City of Lahore. Metropolitan Planning Section Lahore

Development Authority. 1996.

Qurashi, Samina. Lahore: The City Within.

Singapore: Concept Media, 1988.

Credits All

photographs and illustrations courtesy the Aga Khan Fund, MIT Rotch

Collections, unless otherwise noted below: 1.

Courtesy, KK Mumtaz.

2. Courtesy T. Luke Young.

4. Brian B. Taylor, MIMAR 24, 1987.

5. From Pakistan Environmental Planning and Architectural Consultants, Ltd,

"Conservation Plan for the Walled City of Lahore."

6. Courtesy T. Luke Young.

7a. Brian B. Taylor, MIMAR 24, 1987.

9. Courtesy Hasan Uddin Khan.

|

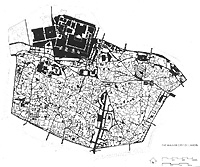

1. Map

of the fortress of Lahore.

2. Traffic outside the walled city.

3. Encroachment.

4. A bazaar in the Walled city

5. Inside View of the Wazir Khan Hamman, before and after restoration..

6. streets in the old area.

7a and 7b. Electrical infrastructure.

8. Sharanwalla gate.

9. Electrical infrastructure.

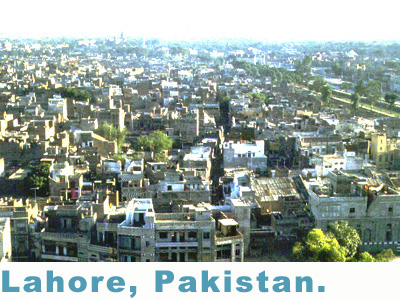

Image10. View of the walled city.

|