Daughters Without Borders

Susan Shepherd

It is not true that we have only one life to live; if we can read, we can live as many more lives and as many kinds of lives as we wish.

-- S.I. Hayakawa

There are two lasting bequests we can give our children. One is roots. The other is wings.

-- Hodding Carter, Jr.

When my sister and I were young, it was understood that we could ask our parents anything, and we did: why the sky was blue, why cats purred but not dogs, why a broken bone was "serious" but a sprained ankle was considered "small potatoes." We only grew more inquisitive with age and I have long since concluded that we must have run our parents ragged with our questions, but if they felt irritation, they never showed it. I remember on one occasion asking my father to tell me what a "moment" was, and getting frustrated when he couldn't tell me how long it was. Finally my pestering drove him to the dictionary, which solved the problem—a moment, it said, was a length of time equal to one minute. I then demanded to know how to tell a minute without looking at a clock, and, after hemming and hawing for a moment, he taught me the "one one-thousand, two one-thousand" trick.

I later concluded that adults must be very poor at telling time. You would ask them a question, they would tell you to wait a moment, and then they would act perturbed when you interrupted them again precisely one "moment" later. The problem grew worse with proximity to the doctor's office, where the receptionist's cheery "It'll be just a moment" would turn into five or ten "moments."

For some reason, when I complained of this to my father, he laughed. This did not improve my opinion of adults' sense of time. Nor their sense of humor, come to think of it.

My parents handled ethical questions in the same way, as soon as my sister and I had grown old enough to ask the right questions. Complex matters came up every now and then, and my parents handled them with care. Mental health issues, for example, came up fairly frequently, as my best friend's mother suffered from episodic depression. I learned about eminent domain just before I turned six, when another friend had to move across town to make way for a highway. I remember feeling frustrated at times by the explanations my parents gave, especially ones that dealt with controversial issues. How cruel of my parents, I thought, to give me thoughtful responses when I wanted the world to divide neatly into the categories of Bad and Good.

I gradually learned that my parents did such things because they wanted us to learn about the world for ourselves. Now that I look back, I doubt they did this deliberately, but whether it was planned parenting or an instinctual response to being asked crazy questions at all hours, the ambiguity of their responses forced me to look for answers of my own. That usually meant reading, or asking slightly different questions, or just mulling their answer over until it fit with the rest of my world. Over time, I grew accustomed to solving problems at least partially on my own. I also had to learn that some questions were beyond my parents to answer, and when that happened, I had to search for a solution myself.

How cruel of my parents, I thought, to give me thoughtful responses when I wanted the world to divide neatly into the categories of Bad and Good.

My parents, however, planned for those questions ahead of time. For my fourth birthday I received a large yellow book with a title something along the lines of What Makes Things Work, which featured schematics of many mechanical devices, among them steamships, refrigerators, and internal combustion engines. On the bookshelf, dictionaries and reference books sat beside the poetry and Little House books. If I asked why "knitting" was spelled so strangely, my parents probably wouldn't know, but I could look it up in the dictionary to see what language it came from.

In this way, my parents reinforced the idea that I could better myself through my own efforts. That proactive attitude was reinforced on a daily basis, both in my parents' actions and in the tales they had to tell. I never knew my grandparents, but my mother told me about them, often in vignettes. While she brushed my hair in the morning, she might talk about her childhood: "You kids are very lucky, you know. When I was young, I had to walk to school." Or she would tell me about her grandmother's family, who had fled a war in Poland, immigrated to America and ultimately settled in Illinois. There, they had worked and saved for money to buy a house. When my grandmother married, she moved and began saving up money again.

My mother always gave me the impression that she had a rocky relationship with her family, but she spoke very respectfully of her mother. "Did you know that Mom never went to high school?" she would ask me, as my sister and I helped her fold clothes or weed the garden. "She quit after eighth grade because she needed the money. The post office hired her. When the old postmaster retired, she took a test to become the new postmaster. Did you know, her score was one of the highest they'd ever seen? That's why you should never treat someone badly just because they didn't finish school."

Even though I never met my grandmother, I felt that I knew her through my mother's stories. I liked her dedication to her family, her sharp wit, and her independence. Her husband died young, and several members of her church pressured her to marry again so she wouldn't have to scramble for money. Perhaps because of their criticism, she worked hard to keep her family together. Even though it meant adhering to a tight budget, she gave her four children the best education the area could offer by sending them to a Catholic school. My grandmother didn't slow down after her kids left the nest, either. Less than a year before cancer claimed her, she would still go hiking to collect the wild strawberries that grew in the area.

My mother had her own set of problems. She had a learning disability that she worked hard to overcome, had to cope with her brother's early death while she was in high school, and was diagnosed shortly after with a difficult-to-treat illness. She traveled westward after her graduation, working wherever she could and spending time in the hospital whenever her illness resurfaced. In California she attended a small Bible college, working in the cafeteria to help pay her way, and graduated with a two-year degree in business. Although she became permanently disabled as a result of her illness, she did not let her disability stop her from succeeding wherever she could. Today, she participates actively in church and in Toastmasters. She also volunteers her time teaching a class about mental health issues in the local community.

My father and my maternal grandmother reacted the same way to adversity. His own father died when he was still in school, and his mother found out she had cancer just as he was starting college. He spent the next seven years caring for his mother, working, and squeezing in classes whenever he could. Perhaps he could have managed if he had had twenty-eight hours per day to work with, but fate restricted him to the usual twenty-four, and he eventually dropped out to devote more time to his mother's needs. This did not in the least prevent him from educating himself, however, or from being successful at his work, where he maintains communication equipment and computers for Fresno's small fleet of fire trucks and police cars.

As I grew up, my family often visited my cousins, so I saw firsthand the contrast between an active, industrious attitude and a lazier one. My uncle Stan worked diligently through high school and college, emerging later with a degree from Caltech. He found a job in the computer industry just as it took off, and raised his own children to be self-reliant and well-educated. But my uncle Robert, rather than working his way up in a company, has always taken the view that certain jobs are "beneath him." He feels that the world is inherently unfair because he has remained largely unsuccessful, but he also will not demean himself by taking a job in a restaurant or fast food establishment and working up. When a problem comes along, he would rather ignore it than deal with it directly. Right now, he is facing a financial crisis because he is unwilling to move from his rented house to a more affordable apartment. I don't know why he feels the apartment would be beneath him—after all, I live in a dorm room, and it suits me just fine—but whatever his line of reasoning, he has made the situation worse by refusing to take action.

By word and by deed, my family members have shown me and my sister the wisdom of working hard and working up, of probing limitations and diminishing them thereby. Our home library is a testament to this. If my parents could not afford to quit work for a four-year college degree, they could still buy books—and did, and do. My parents never directly told me to read. They never had to. I was a living bundle of inquiry, and the answers were arranged by subject on shelves even taller than my father.

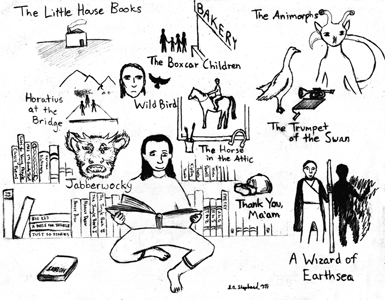

By the time I was eight, my world had expanded a hundredfold when compared to the world I knew when I was four. My sister and I had library cards and caring parents, which, when mixed thoroughly together, produced weekly car trips to the public library. We read about dinosaurs and fairies, Paul Revere and Rosa Parks, life on the frontier and life in the big city. We read silly stories and serious ones, recited "Jabberwocky" and "I Never Saw a Purple Cow," and discussed the humor of "Far Side" cartoons. If you asked me my favorite book, I would alternate between White Fang and Black Beauty, depending on which one I'd re-read most recently.

In retrospect, I realize that my favorite re-reads were books that I could identify with. As varied as these stories were, they often reflected the personal values that my family had instilled in me. I ran the race with Henry in The Boxcar Children, riddled for my life with a treacherous enemy in The Hobbit, and cheered with Top-Sergeant Mahan when the main character of Bruce escaped the German snipers unscathed. Oblivious to the world, I practiced "Mother to Son" and "Da Boy From Rome" until I had memorized them, and sorrowed for T.J. in Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. Lucifer's Hammer and the Little House series developed whole worlds and populated them with fascinating and diverse characters—and taught me that when you have extremely little, every potato counts. I read books about schoolchildren, soldiers, parents, animals, scientists and farmers, with situations as varied as their occupations. But nearly every main character worked hard to succeed despite adversity. Sometimes they failed, only to try again later.

My parents never directly told me to read. They never had to. I was a living bundle of inquiry, and the answers were arranged by subject on shelves even taller than my father.

The books provided rich and varied discussion topics at the dinner table and in private. Many a conversation had its roots in the petty injustices and wider prejudices in the tales we read. I learned more about world history from talking with my parents about The Secret Garden and Stories From Around The World: Tales for Children than I ever did in school. When I discovered science fiction, my already-high interest in science more than doubled, and I began to read Scientific American and Discover magazines for fun.

I can no longer remember when I realized that I had begun to educate myself in the way my parents had. I recall a discussion with my father regarding colleges, however. I would have been in the seventh or eighth grade by then, with a head full of random trivia and a thirst for the stars. I had changed my career preference several times already, and at that time I was probably still in the astronaut or veterinarian phase. Whichever it was, I had noticed that I tended to alternate between careers that seemed awfully dissimilar. It was one thing to be undecided between a career as a nurse and a career as a doctor, I thought, and quite another to have aspirations of writing a book and colonizing Europa and being a soldier all at the same time.

"I just don't see it working," I concluded, having explained my problem to him. "I mean, UC Davis has a good veterinary program, but what if I decide I don't want to be a vet any more? Caltech probably has an astronaut program, but they don't have anything for vets."

My father, who was sitting at the kitchen table at the time, took a sip of his drink and nodded thoughtfully. "Well, the way I see it, you don't have to choose right away. Most colleges allow you to change majors if you change your mind, you know."

"Oh. No, I didn't." I thought a moment. "Dad, what do you think I'd be better at?"

He smiled at that. "I can't really say. You know how it was for me. I sort of took the first option that came along." He saw my nod and took a moment to drink more tea. "I really think that you will do well at anything you choose to do. Even if you decide not to be an astronaut and go into engine repair instead."

We both laughed at that, since I had long disliked anything involving car engines. I regarded mechanical work as evil and complicated, like performing surgery on a brain except that every third engine part had a large WARNING or DANGER sign on it. I cannot remember where the conversation went after that, but I do remember his confidence in me. He thought I would do well—in anything I chose to do.

But if that is so, it is only because my parents raised me to believe that there is no disaster that cannot be overcome, no topic that cannot be broached—and no limit to the knowledge you can gain if you will only search for it. This has caused my sister and me to reach for careers that our parents could never have thought possible for themselves. In a single generation, that philosophy changed my prospects from the dim hope of attending a U.C. to seeking an MIT education, and—who knows?—perhaps it will inspire my own children to reach for the stars.

- Note:

- Books mentioned in this essay include:

The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett, White Fang by Jack London, Lucifer's Hammer by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle, Black Beauty by Anna Sewell, Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry by Mildred D. Taylor, Bruce by Albert Payson Terhune, The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien, the Boxcar Children series by Gertrude Chandler Warner and the Little House series by Laura Ingalls Wilder.

Susan Shepherd lived in Fresno, CA before moving to Cambridge to attend MIT. During her years in Fresno, she took up hobbies ranging from Laser Quest to knitting and everything in between, and is ridiculously proud of having played on Fresno's Laser Quest team in the 2006 and 2007 North American Challenge. She cannot remember when she started writing, but does know that she began to save her work on her computer's hard drive sometime during fifth grade. She has since accumulated more than 400,000 words, and hopes to begin seriously writing out one of her plotted books Real Soon Now.

Susan Shepherd lived in Fresno, CA before moving to Cambridge to attend MIT. During her years in Fresno, she took up hobbies ranging from Laser Quest to knitting and everything in between, and is ridiculously proud of having played on Fresno's Laser Quest team in the 2006 and 2007 North American Challenge. She cannot remember when she started writing, but does know that she began to save her work on her computer's hard drive sometime during fifth grade. She has since accumulated more than 400,000 words, and hopes to begin seriously writing out one of her plotted books Real Soon Now.