The Evolution of a K-12 STEM Outreach Pioneer

Few things tell school kids they’re in for an unforgettable science lesson like letting them touch a Van de Graaff generator and having their hair stand on end.

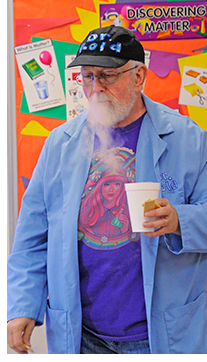

Rick McMaster, as Dr. Kold, demonstrated what happens after eating a graham

cracker dunked in liquid nitrogen.

|

Showing students how to illuminate a pickle like a light bulb by running electric current through it is almost guaranteed to capture their interest in science.

But getting the mayor of the fourth-largest city in Texas to eat a graham cracker that has been frozen in liquid nitrogen—that’s sure proof Rick McMaster has reached the top echelon of volunteer science educators in the United States.

McMaster has shared his passion and expertise in science with hundreds of thousands of children in Austin and central Texas for more than two decades. It’s a community service role he accepted while working for IBM in the early 1990s, after he transferred to Austin to work as a microprocessor design manager.

McMaster has coupled his science education mission with his philosophy of advocating STEM education as a true combination of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. And, he said, some principles modeled by his IUP professors continue to inspire his professional and volunteer work.

He couldn’t have chosen a better time to grow the community science initiative in Austin.

What he took over was a local promotional event for National Engineers Week held each February since the 1950s. A handful of volunteers at IBM, 3M, and Texas Instruments put it together, visiting area schools and capturing students’ interest in science with hands-on demonstrations.

McMaster said he grew the program every way he could.

“I tend to be more inclusive than exclusive, so I just opened it up to anybody who was interested, and we got a lot more people on our steering committee.”

It wasn’t long before they scrapped Engineers Week in favor of Central Texas Discover Engineering and turned it into a year-round program. People from more than 60 companies, business groups, and universities work on it now, and the program reaches an estimated 15,000 students a year.

This community science growth spurt coincided with Austin’s own explosion as a corporate technology center. Dell based its headquarters in Austin, Hewlett-Packard has a center there, and AMD, Applied Materials, Google, and Apple all have a presence in the area. In a nod to California’s technology center nicknamed Silicon Valley, Austin’s chamber of commerce has begun marketing the area as Silicon Hills.

Leading the outreach program gave McMaster a sample of the career he had in his sights in 1968, when he graduated from Kittanning High School and enrolled in what he called the financially affordable, academically well-regarded, and conveniently located Kittanning campus of IUP.

“I started there as a math major, with the intent of teaching high school math, but there really was only sufficient course material at the Kittanning campus for one year,” he said.

He transferred to the Indiana campus for his second year and was surprised at what he learned when he registered for Physics 101.

“As a math major, I was taking transformational geometry, abstract algebra, those kinds of things,” he said. “But I found that I was learning more math in my physics classes than I was really understanding in my math classes.

“It was the practical application of math that really makes sense.”

McMaster switched his major, loaded his schedule with 18 to 21 credits each semester, and earned a bachelor of arts in physics in 1972. He earned a master of science at IUP in 1974. And, he replaced the idea of being a math teacher with a concentration of studies in low-temperature physics. He went on to earn a doctorate in the subject at the University of Connecticut in 1980 and went to work for IBM in the mid-Hudson Valley in New York.

IBM gave McMaster a corporate development assignment from 1988 to 1990, then offered him the microprocessor design management position in a newly formed group in Austin.

It was only natural that McMaster relied on his low-temperature physics background to devise science demonstrations for the Discover Engineering programs in the schools. And giving demonstrations, rather than lessons, has been the key to winning over young audiences, he said.

“The thing that gets kids involved is the excitement of science, not somebody who is just sitting there lecturing to them,” he said.

In May, McMaster took on the identity of Dr. Kold to present “How Cold Is Cold?”

to

fifth-graders at Lake Travis Elementary School in Austin, Texas.

And so, for some programs, McMaster adopts the persona of Professor Sparky for a program called “Microvolts to Megavolts,” demonstrating the powers of electricity. Kids get to play a Theremin, an instrument so sensitive that it changes the pitch and volume of the music when someone simply puts his or her hands near its antennas.

In that same program, Professor Sparky demonstrates the electric pickle. “We attach electrodes and put 110 volts of power through the pickle, and it lights up,” McMaster said. “And it also smells really bad!”

He’s currently working on a newer version, the electric Koolickle, in which the pickle is marinated for a week in cherry Kool-Aid, giving it an extraordinary level of conductivity—soon to be seen on his YouTube channel, he said.

Giving his stage the look of a mad scientist’s lab, McMaster, as Professor Sparky, also demonstrates a Jacob’s ladder, Wimshurst machine, and Van de Graaff generator. Plans are in the works, he said, to incorporate a Tesla coil and a Cockroft-Walton generator into the program.

Other times, he dresses in a lab coat and introduces himself as Dr. Kold. In a program called “How Cold Is Cold,” McMaster uses dry ice and liquid nitrogen for his demonstrations of thermodynamics and makes a batch of ice cream in less than one minute for his grand finale.

For a time, McMaster’s daughter Laura, then in elementary school, took on the role of Arctic Assistant and helped in the demonstrations. McMaster said getting Laura involved showed her and other students that girls, too, could explore STEM-related fields as career choices.

And his programs go on.

In one called “A-Mazing Robots,” kids learn to effectively write instructions for classmates acting as robots to navigate a maze and complete some simple tasks.

In his “Science Friday” visits to Lake Point Elementary School, where the students call him “Rick the Science Guy,” McMaster hands out an assortment of household materials that kids use to create robot arms or puff mobiles, cars they blow on to make go.

At the Bullock Texas State History Museum, he shows students the scientific aspects of events in the exhibits on display.

At every turn, McMaster said, he is showing the importance of the STEM subjects and helping people to understand the real-life ways they are interrelated.

Making that connection is something his IUP professors did well, he said.

John Fox, his advisor, demonstrated it daily. “He was always very down to earth and related what he was teaching to the real world,” McMaster said.

Austin Mayor Lee Leffingwell presented a distinguished service award to McMaster in February for his more than two decades of fostering an appreciation of science among

local students.

|

Optics professor Patrick McNamara memorably told McMaster’s class why the sky is blue. After giving the technical explanation, “he wanted to make sure you really understood it. He set up a different scenario and asked us to determine the color of the sky during sunset on Mars,” McMaster said. “It was how to take the knowledge we gained and apply it to a different situation.”

Another physics professor, Dennis Whitson, who died this past May, taught about nuclear magnetic resonance imaging in the early days of the technology. But he applied the technique to bone tissue, using NMR in the medical field—“taking the basic science and trying to find a real-world application for it,” McMaster said.

A history professor, Larry Miller, brought McMaster into an independent study of the technology involved in the Industrial Revolution and how it affected society.

“So we studied technology, engineering, and science and what they were doing to society as we knew it,” he said. “And all of this was well before anyone was even thinking about the word STEM.”

As an acronym, STEM was first suggested in the early 1990s but didn’t become popular until around 2005. Today, STEM is becoming a household word, McMaster said, and some are rightfully suggesting changes such as STEAM, STEMM, or other combinations of letters as ways to include art, music, or other subjects with real-world connections to the sciences.

“There is definitely a connection between science, technology, engineering, and mathematics to other things in the real world, things that kids are going to care about,” he said.

For his part, McMaster has combined art with science in one of his school programs. He demonstrated how mixing certain colors of paints or projected lights will produce other colors.

And this, he said, is the true underlying concept of STEM education.

“What is important is intercommunication—that you don’t have the artificial silos that people build around themselves where they say, ‘I’m the math teacher, don’t come talk to me about how we can introduce any physics or chemistry or biology into my class,’ while indeed there is a tremendous amount that the kids who are in those math classes could learn in terms of the application of math to the sciences and engineering.”

Twenty years on, Austin city officials have seen fit to honor McMaster for his involvement and leadership in the Discover Engineering program. Austin Mayor Lee Leffingwell and the city council presented a distinguished service award to McMaster in February, commending “his exemplary efforts to promote STEM-related studies and careers among our local students.”

McMaster, who suited up for the formalities as Dr. Kold, asked Leffingwell to help demonstrate the effect of liquid nitrogen on a graham cracker that he dunked into it. A video of the event appears on the Austin city hall website.

Leffingwell took a bite. Frozen to about -320°F, the cracker snapped and crumbled, and fog came out of Leffingwell’s mouth and nose.

The proclamation for McMaster also noted his recent retirement. He left IBM on December 31, after more than 33 years of service.

But there’s no time to be retired.

Rick McMaster and his wife, Leslie Chick McMaster,

outside their home in Austin

|

McMaster has worked with an industry group called ISSIP, the International Society of Service Innovation Professionals, to set up an emeritus program for retiring professionals who want to continue in community service.

The academic environment has the professor emeritus, but industry, for the most part, has no equivalent, he said. This group provides an environment in which they can readily contribute.

“The biggest thing is to encourage ongoing membership,” he said, “so we can take advantage of the broad experiences that people have had in the work environment.”

Curtailing his projects as Dr. Kold, Professor Sparky, and Rick the Science Guy doesn’t seem to be in the picture for McMaster.

“I think I am working harder now than when I worked,” he said. “I look back and wonder how I ever actually managed to work. I’ve gotten involved in so many other things.”

McMaster and his wife, Leslie Chick McMaster, a 1974 graduate of IUP, have been married more than 40 years.

This article, originally entitled "Exploring the Cold, Creating a Spark: IBM Retiree Makes Science ‘Real’ for Central Texas Students" was written by Chauncey Ross, July 30, 2014, and appeared in the Summer 2014 issue of IUP Magazine (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Photographs are by Johnny LeBlanc.

Back to newsletter |