Americans often think of Boston as America’s oldest city. It is revered for its unmatched stock of historic buildings, old transportation infrastructure, and charming traditional New England character. We think of such places as static - homes were built and preserved, streets that were ‘always there.’ But what is often overlooked the dynamics of city; the factories that existed before they were replaced by homes, and the streets that were removed to make way for larger developments. Bounded by Boston’s Emerald Necklace to the west, Brookline Avenue to the north, Kilmarnock Street to the south, and Queensbury street to the east, my site, located in the southern portion of Boston’s Fenway neighborhood, lies at the confluence of forces political, social, economic, and physical. The dynamics of the neighborhood are manifested though changes in land use, transportation, and development of infrastructure.

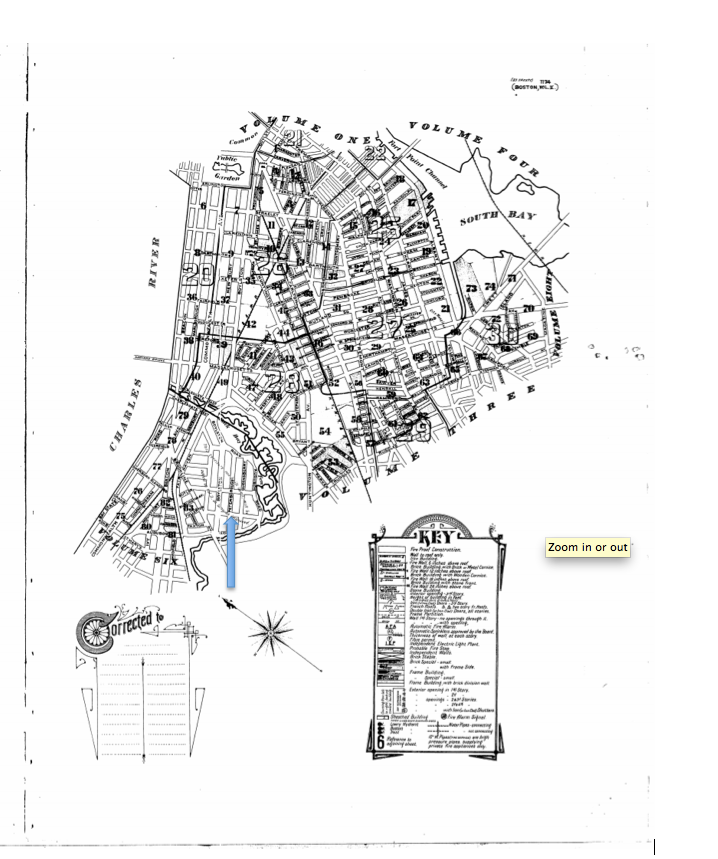

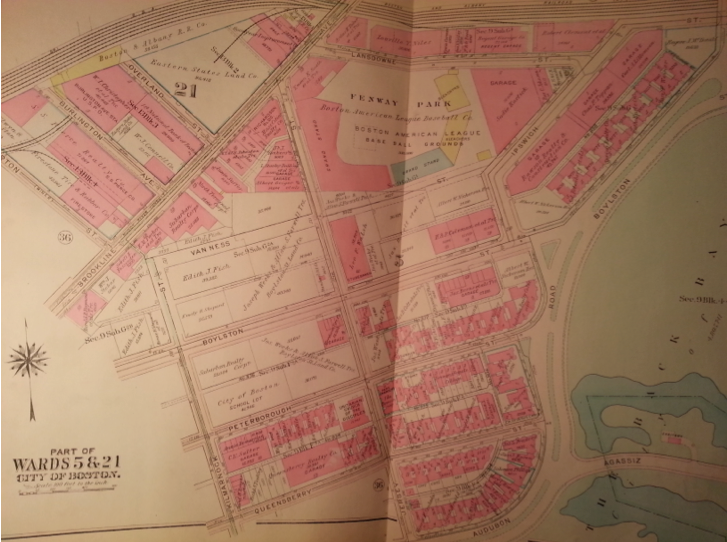

The site is actually the convergence of two sub-sites with distinct development patterns. The first sub-site, the triangle portion bounded by Boylston Street to the south and Brookline Avenue to the north, was developed primarily as a commercial endeavor. It lay at the intersection of two of Boston’s most prominent and heavily travelled commercial thoroughfares, making it a prime commercial location. The second sub-site, the portion south of Boylston Street, was undeveloped as recently as 1897 as shown on the Sanborn Maps (Figure 1). The area was reclaimed as part of Fredrick Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace project, and then was developed into a quiet residential neighborhood (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1897. Highlighted is the note that “this territory not built upon, will be added to Vol 2 as soon as improved.”

Figure 1. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1897. Highlighted is the note that “this territory not built upon, will be added to Vol 2 as soon as improved.”

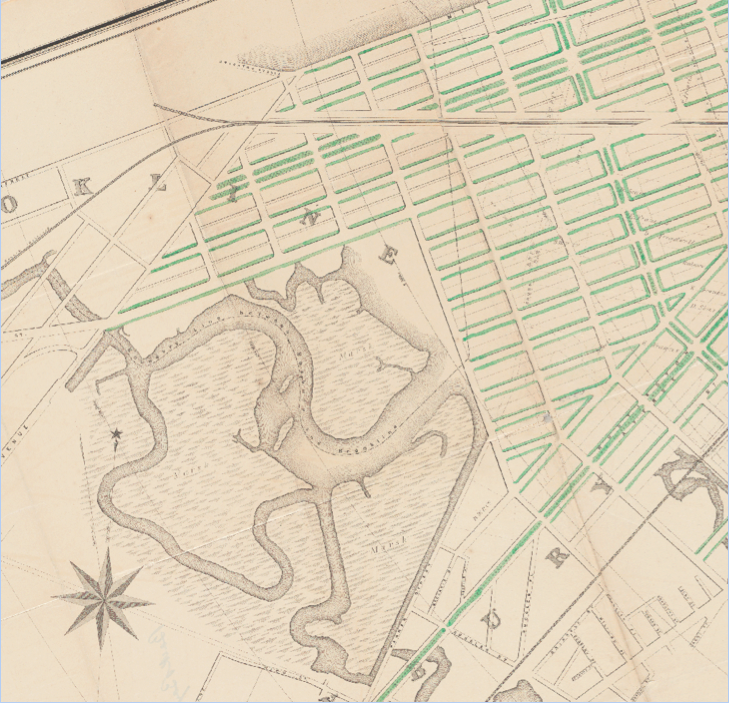

Figure 2. Boston Water Power Company’s proposal for the recently in-filled area of Boston’s Back Bay neighborhood. 1861. The first image shows the original map; the second shows the map overlaid onto a present day Google map, via MIT GeoWeb.

Figure 2. Boston Water Power Company’s proposal for the recently in-filled area of Boston’s Back Bay neighborhood. 1861. The first image shows the original map; the second shows the map overlaid onto a present day Google map, via MIT GeoWeb.

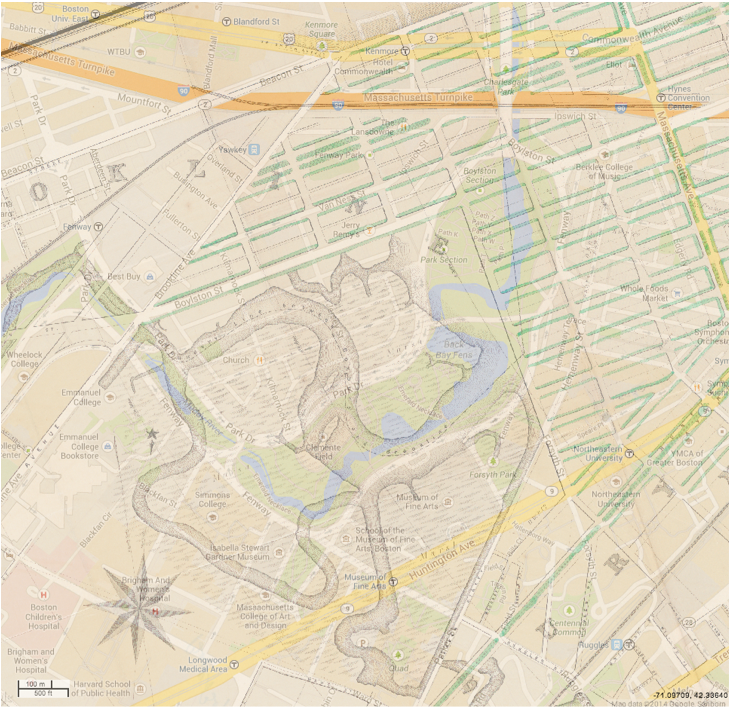

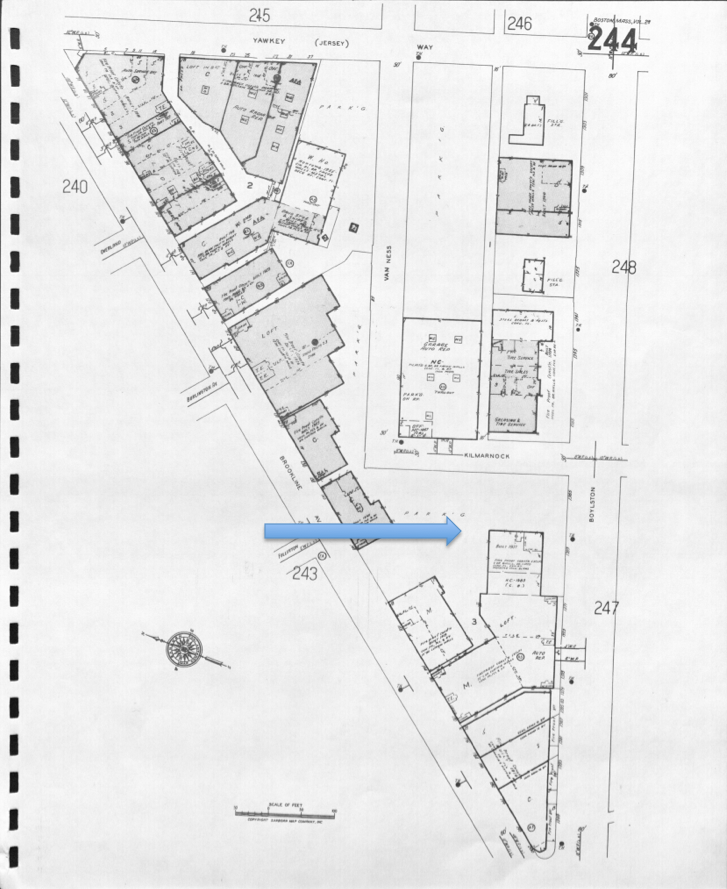

The first sub-site was developed almost wholly as commercial space by retailers. The 1908 Sanborn Map (Figure 3), the first post-reclamation map, is dominated by red, for retail stores. The stores seem to be primarily working class in character, with multiple beer and liquor stores lining the major streets. Most other establishments were automobile related products and services – service stations and tires sales were prominent. This reflects the surrounding area’s working class population; nearby Fenway Park was in part developed in the area during 1911 because of baseball’s long time association with working class audience and players, in addition to the availability of lower cost land and less political resistance to destructive change in an immigrant neighborhood. [1] The only residential building located on the site was a multi-family loft building, located characteristically between a beer store and an automobile service facility. Because this land lay close to the Muddy River, before Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace Project, it was considered undesirable because the river was a dumping ground and often was polluted with sewage. [2]

Figure 3. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps 1908-1938.

Figure 3. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps 1908-1938.

By 1929, a number of changes characterize land use trends over the whole sub-site. Commercial land use continued to strengthen. The only residential space, the loft, was converted into another automotive services facility, a business that relocated to the larger space from their smaller building next door. Some businesses converted from service stations into full service garages, which offered a convenient all-in-one option for car owners to store, maintain, and fuel their cars. Within the first few decades of the twentieth century, the automobile had become a fixture of middle class American life. Many living in the cities aspired to the suburban lifestyle, since “the American Dream was in large part land [ownership]” and this ideal drove car ownership, allowing these automobile centric businesses to thrive. [3]

Another important change was the dislocation of the Hemphill Diesel School, a private English school. As the street continued its march towards total commercial use, the school likely relocated to the other side of the Fens in the Longwood Medical District, among the concentrated cluster of educational institutions including Northeastern University (1898) and Simmons College (1899), as these schools established or expanded their facilities there at the turn of the 20th century. [4] [5] This move was also motivated by the unsuitability of a working class neighborhood for a private educational education.

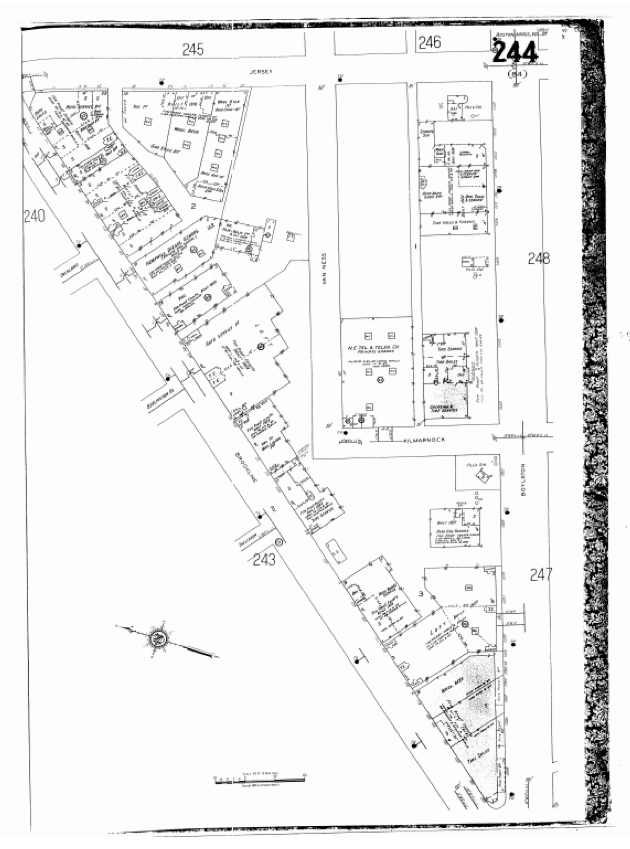

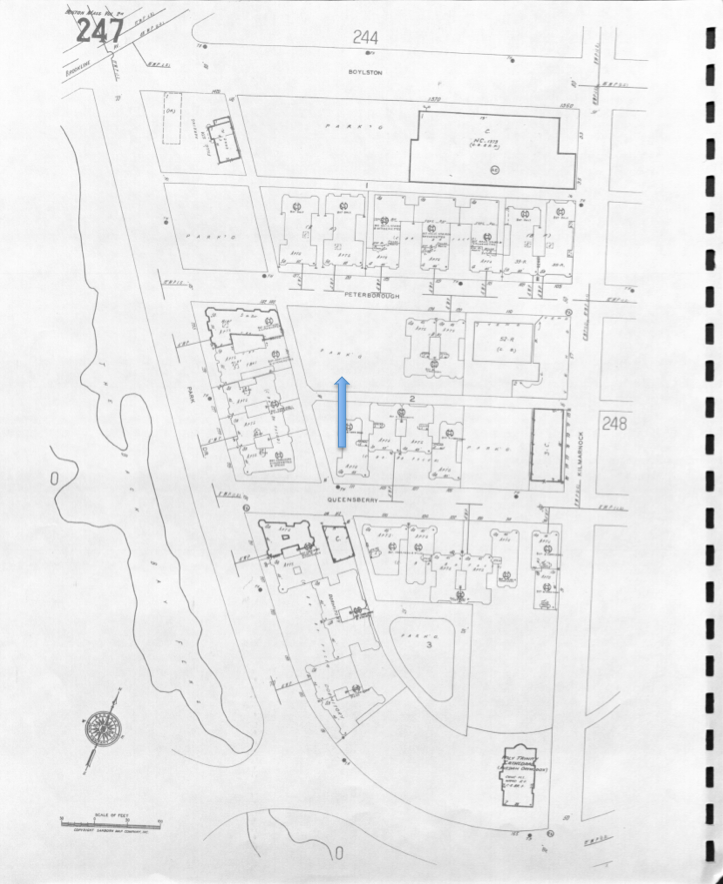

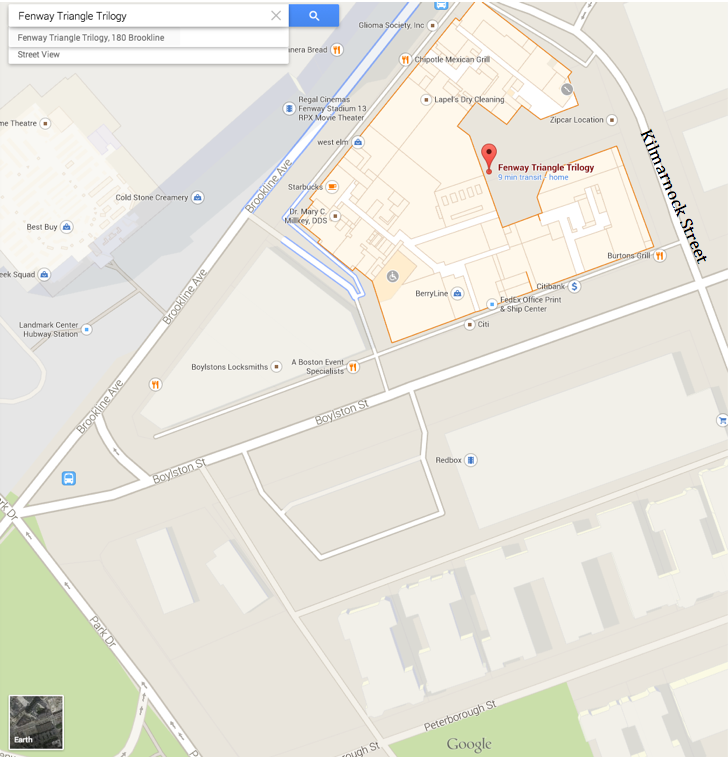

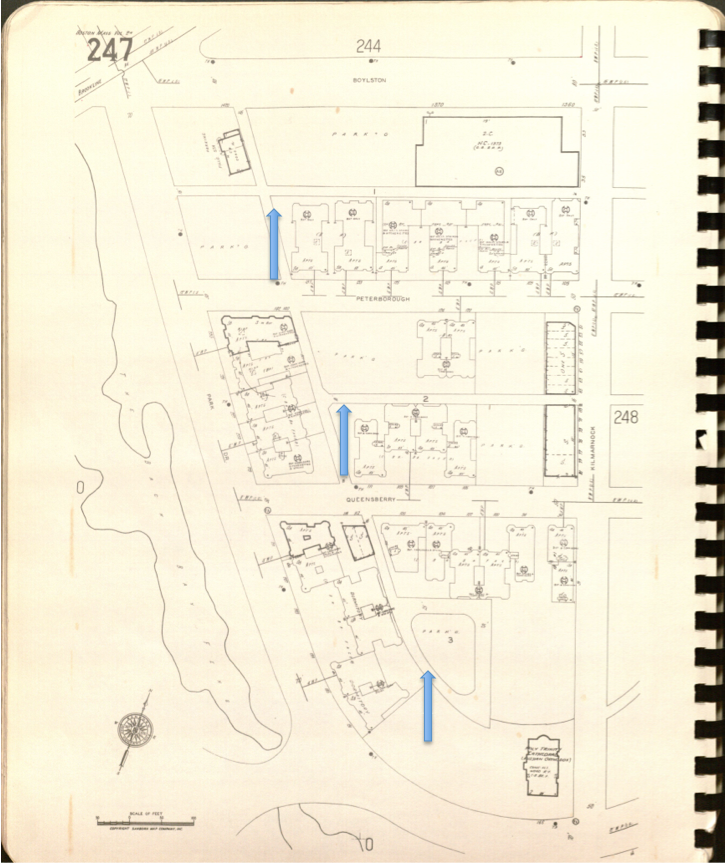

In the present day, with a resurgent interest in city living especially among young people, this area is experiencing brisk redevelopment. Contemporary maps from Google (Figure 5) show a large mixed use development called the Fenway Triangle Trilogy, containing retail on the ground floor and residential on the upper floors. This building was not present as recent as 1992 on the Sanborn Maps (Figure 4). In addition, Kilmarnock Street - which used to terminate into Van Ness Street after a turn - was extended into Brookline Avenue, creating more street facing store frontage, as shown in Figures 4 and 5.

Figure 4. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps 1992. The top image shows the first sub-site, bounded by Brookline Avenue and Boylston Street. It highlights the future location of the new Fenway Triangle Trilogy development, visible in Figure 5. The bottom image shows the second sub-site, and highlights a parking lot that is the future location of Ramler Park. Roach Library.

Figure 4. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps 1992. The top image shows the first sub-site, bounded by Brookline Avenue and Boylston Street. It highlights the future location of the new Fenway Triangle Trilogy development, visible in Figure 5. The bottom image shows the second sub-site, and highlights a parking lot that is the future location of Ramler Park. Roach Library.

Figure 5. Present day Google map highlighting the Fenway Triangle Trilogy development, a recent mixed-use development. (Google Maps 2014).

Figure 5. Present day Google map highlighting the Fenway Triangle Trilogy development, a recent mixed-use development. (Google Maps 2014).

The second sub-site was originally covered by the shallow, polluted waters of the Muddy Charles, until it was reclaimed by Olmsted’s transformative Emerald Necklace project. Figure 2 depicts the site before the Emerald Necklace, with the Muddy River bounded to the north by Boylston Street. Figure 2 shows the proposed street grid of the site by Olmsted, overlaid over the present day street grid of Google Maps. It is notable that the plan for the Emerald Necklace actually opened up public land for development, instead of utilizing the reclaimed land for public development. This change in land use was motivated by the intense pressure in Boston to acquire more developable land, so Boston could compete economically with other rapidly growing American cities like Chicago and Los Angeles, as Professor Spirn mentioned in class. [6]

The area was intentionally developed as a middle-class and upper-middle class neighborhood. It had greater spacing and a propensity of open spaces because of the proximity of the Fens. This change in land use was motivated by “the dread of epidemics” in cities; marketers of the site never “failed to contain the boast that residences among open spaces was more healthy than life in the cities.” [7] Although the “ideal suburb would feature single-family cottages on lots with street frontages of at least one hundred feet, or about four times the width of the average plot in [a] nearby [anchoring city],” Boston’s inflated land values made the proposition uneconomical. [8] Still the apartments had appreciably greater offsets from the streets with gardens filling the space between buildings and sidewalks, especially compared to the first sub-site’s commercial development patterns, which had buildings constructed to the front edge of the property line, as seen in the Sanborn maps (Figure 3, Figure 4).

This dramatic plan’s implementation slowed down during the years of the Great Depression. The resulting economic malaise delayed development dramatically on the city’s last undeveloped parcels. Although the economy made a general recovery by the end of the second world war, “the city’s population [peaking] in 1950 in the days of the post-Word War II housing shortage,” the rise of the automobile altered the land use plans from the original proposals. [9] Land originally allotted for dense multifamily construction was turned into parking lots, as seen in the 1992 Sanborn Maps (Figure 4). It was not only the increased premium on automobile-centric conveniences that led to this development - the white flight to the suburbs and the general economic malaise Boston experienced in the 1950’s as described by Warner reduced immediate real estate demand and pushed the economic scales towards use as parking lots. [10]

More recently, a parking lot on Peterborough Street was redeveloped into a half-acre park via a private donation. [11] It did not appear on Sanborn maps as recent as 1992 (Figure 4), but was a significant part of the neighborhood’s character during my on-site investigations. The park has a success, turning a blighted parking lot in an otherwise densely built neighborhood into a community gathering point. The community organized around the park, and now holds regular concerts to bring the residents together. Ramler Park is an interesting push back against the suburban ideal of isolation and private ownership. It is a shift towards the creation of shared community space, and sets an example for how diverse communities in Boston can build community and healthy, sharable spaces.

Before the opening of the green line stop, the businesses on Brookline and Boylston served primarily the working class immigrants and middle class populations on adjacent blocks, as well as the automobile commuters who lived in farther away cities like Brookline and Allston. As a result, these streets were planned and built wide in a rectilinear pattern, in contrast to the free-flowing and narrow European-style streets Boston is otherwise famed for (Figure 2).

The Kenmore T stop opened in 1932, during the initial development of the residential portion of the site. The stop was a half-mile from the site; I measured a ten-minute walk during my visit. Brookline Avenue is dominated by commercial land use in large part because of the heavy pedestrian traffic it carries from southern residential section to the T stop in Kenmore Square. The link the rail line provided to the city was vital; instead of relying on uncomfortable and slow horse-drawn omnibuses, it allowed the area to flourish into what Jackson describes as a “streetcar suburb,” or here, more aptly, a streetcar neighborhood. [12]

The purpose of alleyways also evolved over time. Early developments attempted to make behind-home alleyways as small as possible in order to maximize the use of each parcel of land. The alleys were actively avoided by residents unless absolutely necessary, as Jackson describes:

Because regular garbage collection was rare before the Civil War, most families threw their refuse out the doors to the scavenging dogs and pigs. Except for the regular visits to the privy vault or outhouse, most people avoided the back yard entirely; a social occasion there would have been unthinkable. [13]

By the time the first apartments were built in 1908, widely available city services required such allies for utilities for the multistory, multi-family apartment buildings that were standard in South Fenway. These laws were manifested in the developments – they are visible in Figure 6, a 1974 Sanborn Map. Later, with the widespread prevalence of the automobile but not enough supporting infrastructure, many of these alleyways were used for parking vehicles of residences, a practice that is now ubiquitous.

Figure 6. Sanborn 1974. Alleyways highlighted. The alleyways often lead to parking areas behind the buildings, and are otherwise used for car storage and city services as well.

Figure 6. Sanborn 1974. Alleyways highlighted. The alleyways often lead to parking areas behind the buildings, and are otherwise used for car storage and city services as well.

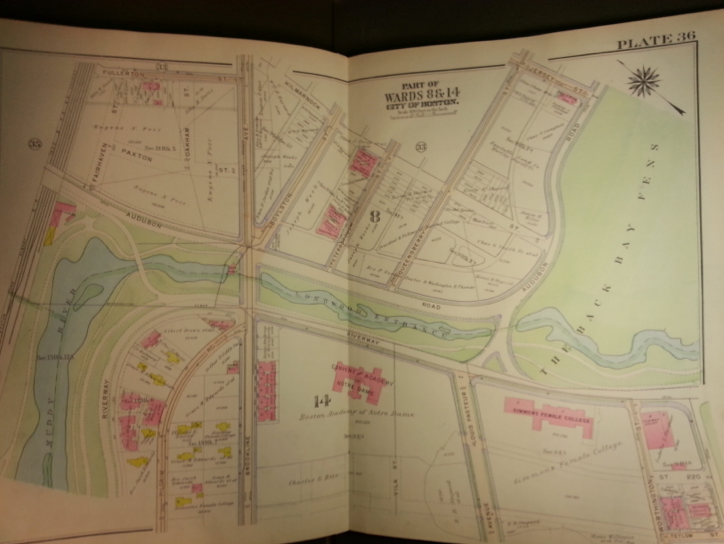

Despite the concessions made to the automobile, walking remained a major mode of transportation. The Bromley property maps indicate that many of the buildings were owned by nearby Simmons College, housing either staff or students (Figure 7). The 1917 map also shows some of the property was also originally allotted to the “President & Fellows of Harvard College,” likely so the president could oversee Harvard Medical School, also located in the Longwood Medical District across the Emerald Necklace (Figure 8).

Figure 7. Bromley 1928, depicting the buildings at and surrounding the site. Several are owned by Simmons College.

Figure 7. Bromley 1928, depicting the buildings at and surrounding the site. Several are owned by Simmons College.

Figure 8. Bromley 1917 showing the land ownership in the developing area.

Figure 8. Bromley 1917 showing the land ownership in the developing area.

Jackson describes how writers of a century ago “testified to the magnetic quality of American metropolises”. [14] Today, the city of Boston again attracts students, educators, and professionals from around the world. This growth has put strain on the city’s limited land and infrastructure resources, just as it did one hundred years ago. Because of innovative land management projects like the Fens, combined with improvements in the transportation infrastructure, the city improved both its natural environment while opening up more developable property. Although economic forces and changing transportation preferences resulted in the underuse of land as parking lots, recent developments have turned previously neglected parcels into vital residential and community space, filling the needs of the resurgent urban educated class, a trend not only in Boston but also in other thriving global cities. Because of community involvement and political processes, Boston is once again well positioned to continue its growth into the future while preserving the characteristic elements of its vital history. It offers lessons Asian cities like Mumbai, Beijing, Shanghai, and New Delhi undergoing transformative development, a model for how to build livable, economically flexible, and historically significant cities.

1. Alan E. Foulds, Boston's Ballparks and Arenas, (Boston: Northeastern University, 2005), 48.

2. Anne W. Spirn, The Granite Garden: Urban Nature And Human Design, (New York: Basic Books, 1984), 43.

3. Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 54.

4. “Simmons College Homepage,” Simmons College, accessed April 4 2014, http://www.simmons.edu/

5. “Northeastern University – Home,” Northeastern University, accessed April 4 2014, http://www.northeastern.edu/

6. Spirn, Anne W, “Natural Processes over time” (presentation, The Once and Future City, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, February 2014).

7. Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 58.

8. Ibid 65.

9. Sam B. Warner, Mapping Boston, (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2001), 11.

10. Ibid.

11. “Friends of Ramler Park,” Fenway Civic Association, accessed April 4 2014, http://fenwaycivic.org/get-involved/friends-of-ramler-park/.

12. Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 91.

13. Ibid 56.

14. Ibid 68.

Boston Water Power Company. “Back Bay, Boston, Massachusetts, 1861.” Cambridge: Harvard Map Collection, Harvard College Library, 2007. Via MIT GeoWeb. http://arrowsmith.mit.edu/mitogp/openGeoPortalHome.jsp?layer%5B%5D=HARVARD.SDE2.MATWN_3764_B6_1868_E2&layer%5B%5D=HARVARD.SDE2.MATWN_3764_B6_1874_G2&layer%5B%5D=HARVARD.SDE2.MATWN_3764_B6N2_1814_D4&layer%5B%5D=HARVARD.SDE2.MATWN_3764_B6G52_1894_O4A&layer%5B%5D=HARVARD.SDE2.MATWN_3764_B6_2B2_1861_B6&minX=-71.114255915503&minY=42.332120509349&maxX=-71.067864428382&maxY=42.354451173394

Foulds, Alan E. Boston's Ballparks and Arenas. Boston: Northeastern University, 2005. Via Google Books. Accessed April 4 2014. http://books.google.com/books?id=dQWzRxP-a7sC&pg=PA48&hl=en#v=onepage&q&f=false

“Friends of Ramler Park.” Fenway Civic Association. Accessed April 4 2014, http://fenwaycivic.org/get-involved/friends-of-ramler-park/.

G.M. Hopkins & Co. “Map of the city of Boston and its environs, 1874.” Cambridge: Harvard Map Collection, Harvard College Library, 2004. Via MIT GeoWeb. http://arrowsmith.mit.edu/mitogp/openGeoPortalHome.jsp?layer%5B%5D=HARVARD.SDE2.MATWN_3764_B6_1868_E2&layer%5B%5D=HARVARD.SDE2.MATWN_3764_B6_1874_G2&layer%5B%5D=HARVARD.SDE2.MATWN_3764_B6N2_1814_D4&layer%5B%5D=HARVARD.SDE2.MATWN_3764_B6G52_1894_O4A&layer%5B%5D=HARVARD.SDE2.MATWN_3764_B6_2B2_1861_B6&minX=-71.114255915503&minY=42.332120509349&maxX=-71.067864428382&maxY=42.354451173394

Google Maps. Boylston Street and Brookline Ave. Last modified 2014. https://www.google.com/maps/place/Boylston+St/@42.343314,-71.0996516,18z/data=!4m2!3m1!1s0x89e37a0fcee87b83:0xef7cad061437154e

G.W. Bromley & Co. Boston MA. Boston: G.W. Bromley & Co. 1917.

G.W. Bromley & Co. Boston MA. Boston: G.W. Bromley & Co. 1928.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

“Northeastern.” Northeastern University. Accessed April 4 2014, http://www.northeastern.edu/.

“Simmons College Homepage.” Simmons College. Accessed April 4 2014, http://www.simmons.edu/.

Sanborn Map Company Inc. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps Boston MA. Pelham: Sanborn Map Company. 1897. Via MIT Rotch library website. Accessed April 4 2014. http://sanborn.umi.com.libproxy.mit.edu/ma/3693/dateid-000019.htm?CCSI=254n

Sanborn Map Company Inc. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps Boston MA. Pelham: Sanborn Map Company. 1908-1939. Via MIT Rotch library website. Accessed April 4 2014. http://sanborn.umi.com.libproxy.mit.edu/ma/3693/dateid-000019.htm?CCSI=254n

Sanborn Map Company Inc. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps Boston MA. Pelham: Sanborn Map Company. 1974.

Sanborn Map Company Inc. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps Boston MA. Pelham: Sanborn Map Company. 1992.

Spirn, Anne W. “Natural Processes over time.” Presentation in The Once and Future City class, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, February 2014.

Spirn, Anne W. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature And Human Design. New York: Basic Books, 1984.

Warner, Sam B. Mapping Boston. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2001.