This

week I don’t have any comments to add about these excerpts even though

they stood out as I went through the reading. Nonetheless, I think it

is still worth sharing even though I have reserved comment.

Excerpts from Language of Landscape:

Through grammar, meanings are shared; grammar is an aid to

reading and telling landscape more fluently, deeply, expressively, and

gracefully. The language is living, so grammar – derived from speech

and the literature of landscape – is timeless, yet not rigid, but

evolving and various. There are formulas, rules – artifacts of

inherited usage – but also free expression, the renewal of language

through the invention of new patterns.

Readers do not use grammar the same way tellers do. Readers

decode meaning, move form perception of an element to an appreciation

of its function, to understanding. Tellers have a message to relate and

search for ways to express its significance by the choice and ordering

of landscape’s elements.

Multiple, overlapping grammars is what makes human landscapes so interesting and complex. Pg 168.

Just a word’s meaning is mere potential until shaped by specific

relationships with other word in context of phrase, clause, or

sentence, so the meaning of an element of landscape is merely immanent

until shaped by relationships with other elements in context. Pg

170.

The successive sometimes hierarchical, relationship of parts and

wholes in landscape gives its language a nested structure. Rules of

grammar – modification, agreement, correspondence, subordination, and

coordination – apply across scales, as well as within. Pg 173.

Disorder, wrote Rudolf Arnheim, “is not the absence of all order

but rather the clash of uncoordinated orders.” Arnheim defined order as

“the degree and kind of lawfulness governing the relations among the

parts of an entity” and complexity as the multiplicity of the

relationships among those parts. Pg 180.

Local landscape dialects emerge out of dialogue with enduring

contexts of place; traditional vernacular landscapes are a consequence

of collective learning, trial and error, finding what works and

repeating it, refining through experience. They tend to correspond more

closely to local conditions than do landscapes of cultures of highly

developed technology. Pg 181.

As I keep revisiting my, I keep thinking about the theme of

ephemeral vs. enduring from last week’s reading. I keep dwelling on the

notion that the physical passage through my site is an ephemeral

experience, whilst the actual thought of it – and of going down or

underground or under – has a much more pervasive meaning the extends

prior to and beyond the experience of passing through the tunnels.

Every so often I come upon a doorway with yet another staircase, but

with stairs leading down. I have only taken one of these stairs once. I

dare not take any of the others. I think I am actually scared to. I ask

myself (am I not on the lowest level already?.. I don’t think I want to

go down any further…).

If you take the elevators in building 10 down to the basement, then

turn left onto the infinite corridor, and then another left into

building 13, at first you come upon a pleasant area where there are

large half-wall windows, opening onto another hidden courtyard garden.

This is my favourite garden on campus. It has many trees and some

flowers. There are concrete tiles creating a footpath from the western

tip of building 13 to the stairway leading to the small recessed

entryway of building 10. A couple weeks ago I noticed that the

bottom-most window along this half-wall is broken. Since then, I have

been toying with the idea of how best to photography this broken window

with the one shard dangling from the top of the frame and crack lines

radiating through the rest of the glass that is still set in the frame.

Should I photograph it from the outside looking in, or from the inside

looking out. I finally decided that from the inside looking out was

better captured the context of this window in its setting.

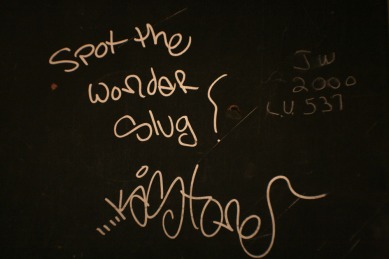

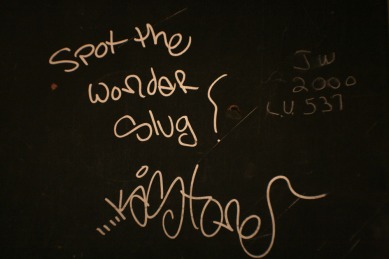

Along the eastern end of building 13 is a very narrow corridor with

chain-linked storages areas on one side and a smooth plaster wall on

the other side. At the end of this corridor, just next to the exit sign

is one word of graffiti. Then, on the doorway leading to the escape

stairway is another bit of graffiti which says, “spot the wonder slug

?”. I have no idea what this means but it’s so amusing to me; I wish

there was more graffiti in these tunnels. This got me wondering why

indeed there was not more graffiti in these tunnels. The wall I just

described would make a good canvas for graffiti. If only I was skilled

at it, I would venture to do some artwork on these walls. My greater

hope is that someone will read this blog and become motivated to apply

some artwork to some of these drab walls.

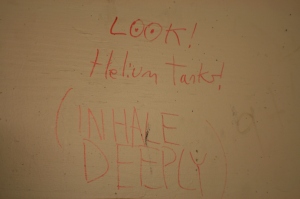

I subsequently did manage to find some more artwork underground.

Perhaps this is the greatest treasure hidden down there. I was only

able to see the full extent of it because someone had left one of these

chain-linked cages unlocked. Up the stairs onto to make-shift wooden

platform crossing some huge pipes are the tags of MIT’s hackers! From

behind the cage one can only get a slight glimpse of one of the tags

which resembles the label of Jack Daniel’s whiskey bottle. I crawled

over the platform into the alcove which housed the tags of about 7

hackers. They were huge! Then I looked up, and there were writings on

the ceiling and ducts – remarkable because they were about 30 feet

high! All the while I was there I was nervous because I knew that I was

actually below the tunnels at this point, and also fearful that I might

be discovered in what I perceived as some sort of “sacred”/secret

space. Alas, I have not disclosed the location of this shrine, and I

don’t intend to…

After weeks of exploring the tunnels

from within, I have begun to explore them from the outside. In most

instances reference to this underground space is through office windows

opening out to some courtyard garden. The majority of the tunnels are

double-loaded corridors (flanked with rooms on both sides), however on

a few occasions they are single-loaded and usually at these intervals

they run alongside courtyards providing passers-by with a relieving

reprieve from the confinement of the tunnels. The designers of these

buildings should be commended for allow passers-by a break from the

constant enclosure of the corridors and a chance to enjoy a softer,

more natural view.

Thus far I have only shown my site in static frames. None of my

photos contain images of people using the space. This will come in the

next section – Poetics. The static elements set the tone and

give the sense of place. The various ways in which people utilize the

spaces creates a sort of poetry in motion. From the glass-blowers

drawing glowing, molten glass out of the kiln; to the researchers

scurrying into their labs; to the traversers using the tunnels either

to escape the pedestrian traffic along the above floors or to escape

the outdoor weather, or both; to the occasional cyclist sprinting

through the underground labyrinth; to the custodians stamping their

timecards as they check in for (or out of) their shifts.

This is another excerpt from a book I was reading for another

assignment. I think it presents very pertinent notions of how one

experiences place. Once again, I will withhold comment and simply share

the inspiring text…

Excerpts from Sense of Place: Its Relationship to Self and Time by Yi-Fu Tuan

Sense of place would seem clearly a function of time: a period

of time must lapse before one can have a sense of place. Yet this is

not quite right for, as we shall see later, we can identify with a

place immediately. More true is this, place must stop changing for a

human being to be able to grasp it and so have a sense of it. Some

places change so slowly that, from a human perspective, they are

timeless. Large natural features – mountains, forests, and rivers – are

outstanding examples. People come and go, generations pass, but the

mountain or river stays much the same. Some old habitations seem

changeless. Of course, they have a history, but that history – history

of development – came to a stop, or seems to have come to a stop; and

thereafter, human beings see it and remember it as changeless. A key

characteristic of modern times, as we all know, is the rapidity and

ubiquity of change… How can we develop as sense of place – f any place

– if nothing stays put?

Even if places stay put and change little with time, human

individuals do not. They age. The child sees the mountain or village

one way, the adult another. At what period in our growth is our sense

of pace fixed. Not in childhood when every year brings about a new way

of seeing and understanding. The answer would have to be maturity – a

phase in life conceived as a standstill of some duration in the human

life cycle, somewhat analogous to the solstice in the passage of the

sun. In the course of this standstill a firm sense of place develops

that alters little thereafter. Our sense of place thus stabilized, we

count on the material places themselves to be stable, especially those

that are important to our emotional well-being.