(Text, unless otherwise noted, is the author's own)

Urban

Trees, Urban Heat Island, and Energy

The urban heat island is

the phenomenon whereby urbanized areas exhibit significantly higher temperatures

(generally at night-time) than their outlying, rural areas. This phenomenon

has been linked to poor air quality, uncomfortable and sometimes dangerous urban

temperatures, and increased energy use (for cooling). Augmenting greenspace

in urbanized areas is currently recognized as one of the key strategies for

urban heat island mitigation. Ambient temperatures vary throughout the city

as a function of sites’ design and materials. Many studies have noted

that sites with high tree coverage tend to have lower temperatures than sites

with few to no trees.

Trees accomplish this by:

1. directly shading surfaces and reducing the amount of radiation absorbed,

stored, and released by urban surfaces

2. evapotranspiring and converting radiation to latent heat, decreasing that

which is converted to sensible heat

3. altering airflow and the transport of water vapor and energy

(Mcpherson et al 1995)

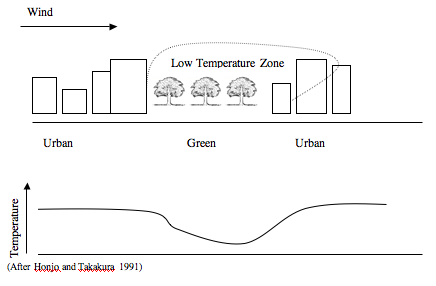

The so-called ‘oasis’ effect produced by vegetated urban sites is

well documented (see Figure 1). A review by Taha (1997) found that vegetated

spaces could be 2-8°C cooler than their surroundings. The same review found

that studies in Montreal, Tokyo, and Davis, CA reported that vegetated regions

and parks were 1.6°C, 2.5°C, and 2°C respectively cooler than neighboring,

non-green regions.

The cooling effect that vegetation has on site microclimate is largely undisputed.

Figure 1. Temperature effects of urban greenspace

The lowered temperatures achieved by greenspace not only positively affect urban

health and comfort, but also lower energy use in commercial buildings and residences.

Many energy companies are even encouraging customers to use trees to cool their

buildings. The most recommended way to cool buildings is through the direct

shading of surfaces.

Before the introduction of mechanical systems, tree shade was often used to

passively lower the temperatures of structures (Burberry 1978). A number of

recent studies have demonstrated that thoughtful landscaping is still an efficient,

though largely overlooked, way to control building temperatures and lower energy

demand (Meier 1990). Carefully planted deciduous trees provide shade where needed

in the summer, but lose their leaves in winter and do not significantly block

solar gain. A modeling effort examining residential energy use found that trees

placed to shade a home’s roof, as well as its east and west side, reduced

heating and cooling energy costs by 20-25% when compared with the same house

in the open (Heisler 1986). Akbari et al (1997) planted 16 trees at two residential

sites in Sacramento, CA and reported that summer cooling savings averaged 30%.

While most studies have looked specifically at residential units, which, given

their size, are easier to influence with plantings, there is evidence that larger

structures can benefit from properly placed vegetation as well. An experimental

study of a university building in Athens, Greece found that un-shaded surfaces

consistently had over twice the net radiation and thermal flux values as the

shaded surface (Papadakis 2001). Such studies can allow the effects of urban

trees to be quantified in terms of energy savings, providing an incentive for

their planting and care.

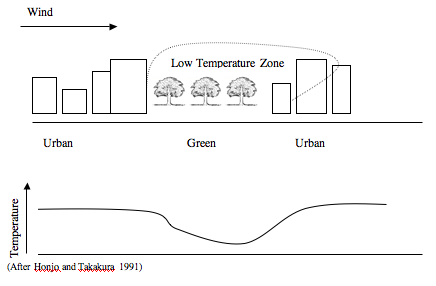

Figure 2. The impact of trees on household temperature and

energy use

(Image source: American

Forests)

By blocking cold winter winds, evergreen trees and shrubs can reduce heating

costs as well (see Figure 2)

There are some caveats to these benefits. First, they are fully realized only

when the trees are mature. This can take 10-15 years, although fast growing

species are also available. Second, planting methods for energy savings may

vary in different climates. Clearly in regions that have significantly more

heating degree-days than cooling ones, intercepting solar radiation, even minimally,

could raise instead of lower energy costs. Thus, air conditioning savings are

likely to be greater in hot climates. However it is generally agreed that savings

can also be achieved in temperate climates with vegetation that shades surfaces

in the summer, without blocking any southern exposure in the winter (Sand 1991).

Air

Pollutant Removal and Carbon Dioxide

Pollution

(Text Source:

Nowak,

D., USDA)

Trees remove gaseous air

pollution primarily by uptake via leaf stomata, though some gases are removed

by the plant surface. Once inside the leaf, gases diffuse into intercellular

spaces and may be absorbed by water films to form acids or react with inner-leaf

surfaces. Trees also remove pollution by intercepting airborne particles. Some

particles can be absorbed into the tree, though most particles that are intercepted

are retained on the plant surface. The intercepted particle often is resuspended

to the atmosphere, washed off by rain, or dropped to the ground with leaf and

twig fallg. Consequently, vegetation is only a temporary retention site for

many atmospheric particles.

In 1994, trees in New York City removed an estimated 1,821 metric tons of air

pollution at an estimated value to society of $9.5 million. Air pollution removal

by urban forests in New York was greater than in Atlanta (1,196 t; $6.5 million)

and Baltimore (499 t; $2.7 million), but pollution removal per m2 of canopy

cover was fairly similar among these cities (New York: 13.7 g/m2/yr; Baltimore:

12.2 g/m2/yr; Atlanta: 10.6 g/m2/yr)h. These standardized pollution removal

rates differ among cities according to the amount of air pollution, length of

in-leaf season, precipitation, and other meteorological variables. Large healthy

trees greater than 77 cm in diameter remove approximately 70 times more air

pollution annually (1.4 kg/yr) than small healthy trees less than 8 cm in diameter

(0.02 kg/yr)k. Air quality improvement in New York City due to pollution removal

by trees during daytime of the in-leaf season averaged 0.47% for particulate

matter, 0.45% for ozone, 0.43% for sulfur dioxide, 0.30% for nitrogen dioxide,

and 0.002% for carbon monoxide. Air quality improves with increased percent

tree cover and decreased mixing-layer heights. In urban areas with 100% tree

cover (i.e., contiguous forest stands), short-term improvements in air quality

(one hour) from pollution removal by trees were as high as 15% for ozone, 14%

for sulfur dioxide, 13% for particulate matter, 8% for nitrogen dioxide, and

0.05% for carbon monoxide

Carbon

Dioxide

(Text Source:CITYgreen

Manual)

Trees remove carbon dioxide from

the air through their leaves. Carbon storage is the total amount of carbon held

in a

tree’s wood (biomass). Carbon sequestration is the rate at which trees

store carbon. Older trees have more carbon storage; younger trees have a higher

sequestration rate. Approximately half of a tree’s dry weight is carbon.

For this reason, large-scale tree planting projects are recognized as a legitimate

tool in many national carbon- reduction programs.

Urban

Forest and Water

Urbanization transforms

the landscape from one dominated by forests, wetlands, and vegetation to one

covered by buildings, asphalt, pavement, and compacted soils, all impervious

to water. Impervious surface coverage (ISC) has been recognized as an accurate

indicator of urbanization intensity (i.e. increases in density, energy/unit

area etc.) (Paul and Meyer 2001, Brabec et al 2002). Heavily urbanized regions,

such as cities and downtown areas, can have over 90% impervious surface cover.

In a natural environment, precipitation is returned to the atmosphere via evaporation

and transpiration, infiltrates into soil, recharges groundwater, and enters

into receiving surface waters. Surface runoff, one of the main sources of water

for streams and lakes, is generally the end stage of this cycle, and occurs

only when the amount of precipitation exceeds the rate at which it can be evaporated

or infiltrated. In urban environments ISC reduces opportunities for water to

flow into the earth, and the displacement of vegetation decreases the amount

of evapotranspiration that can occur. Storm water pathways are thus limited

and the majority of rainwater becomes runoff. The runoff tends to move more

quickly through an urban environment than a natural one, as surfaces are smoother

(lowered coefficient of roughness) and flatter (lowered storage capacity). This

is also a result, an intended outcome in fact, of conventional storm water systems,

which have been engineered to provide efficient and rapid removal of rainwater

from urban surfaces. Landscapes have been graded, piped, and paved in an effort

to quickly move water off urban surfaces to storm water sewers and into treatment

plants, or, more commonly, into receiving waters (Coffman et al 1998). The overall

result is a larger quantity of runoff moving across surfaces and entering receiving

waters more rapidly than it would have pre-development (see Figure 3). In addition

to causing erosion and incision in urban waterways, the runoff mobilizes the

myriad contaminants that lie across the urban surface, such as salts, metals,

particulates, and sediments.

Figure 3. Impact of development

on runoff

(Image

Source)

Trees and open spaces in cities play

an important role in runoff sequestration and flood protection by:

1. increasing the permeability of surfaces

2. increasing depression storage

3. allowing infiltration and ground water recharge

4. allowing infiltration and pollutant remediation

Trees intercept large quantities of water with their leaves and bark, slowing

the flow of runoff and increasing opportunities for evaporation. Their roots

increase the permeability of soils, aiding infiltration and groundwater recharge.

A study on one large deciduous tree in Southern California found that it reduced

runoff by over 4,000 gallons per year (Xiao 1998). This type of mitigation is

especially beneficial because it is an accessible technology and can be applied

on many scales. Furthermore, unlike methods such as detention basins, trees

and vegetation control runoff at the site.

Trees and vegetation can

also remediate water, taking up nutrients and degrading pollutants.

Wildlife

Habitat

(Text Source: San

Francisco Dept

of Environment.)

Trees provide food and shelter for urban wildlife. Many types of insects feed

on trees, and in turn provide food for other insects and birds. Some birds and

small mammals feed directly on tree pollen, flowers and fruits. Birds also use

tree branches for courting displays and nesting.

Microbial populations that form the bottom of the food chain are significantly

higher in the soil surrounding tree roots. Many species of fungus (mycorrhizae)

are intimately associated with tree roots. Mushrooms and other fruiting bodies

of these fungi provide an additional food source for urban wildlife.

Groups of urban trees near water sources can support an even wider variety of

insects, birds, small mammals and reptiles. You can maximize the benefits of

trees to native wildlife species by eliminating the use of toxic insecticides

and fungicides, planting trees in uncovered tree pits, and planting native tree

species.