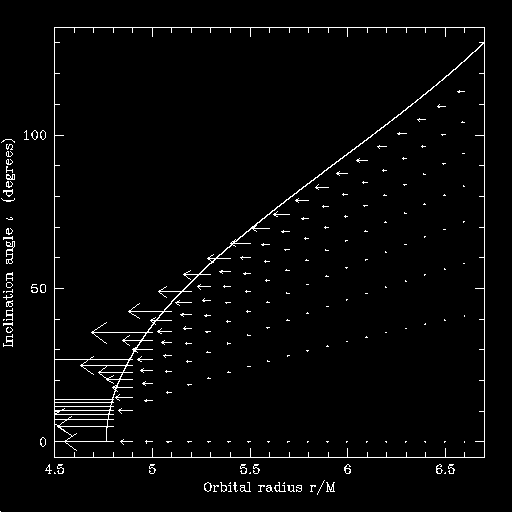

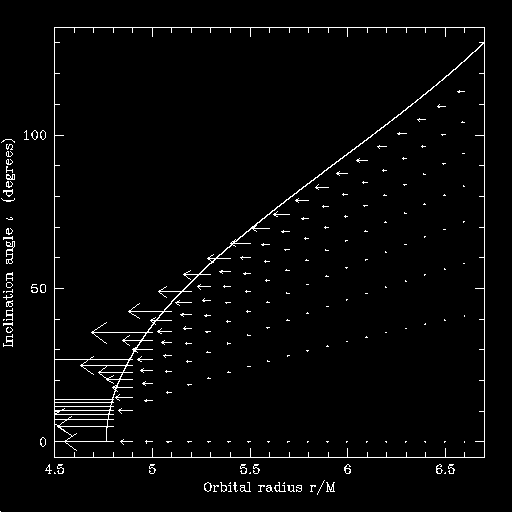

First, here's a plot showing the evolution vectors - the direction in r and iota in which the orbit is driven:

The line in this plot gives the angle at each radius of the least-bound stable orbit; orbits at higher inclination angle are unstable, and so are astrophysically irrelevant. The tail of each arrow gives the (r, iota) coordinates of a particular orbit. The arrow points in the direction to which radiation reaction pushes the arrow, and the length is proportional to the rate at which the evolution occurs.

Using this field of data points, I evolve a set of orbits. The orbits start at r/M = 4 and various values of iota. I use cubic spline interpolations to find the values of dr/dt and d(iota)/dt at arbitrary coordinate points, given the field of data shown above.

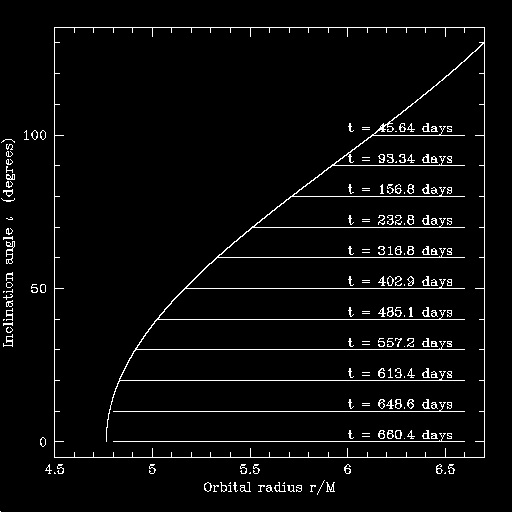

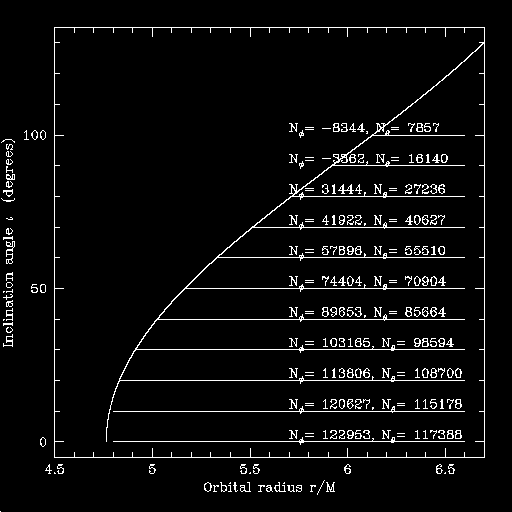

Here is a set of inspiral trajectories computed for a 1 solar mass body spiraling into a 106 solar mass black hole:

The time given at each trajectory is the number of days it takes to spiral in.

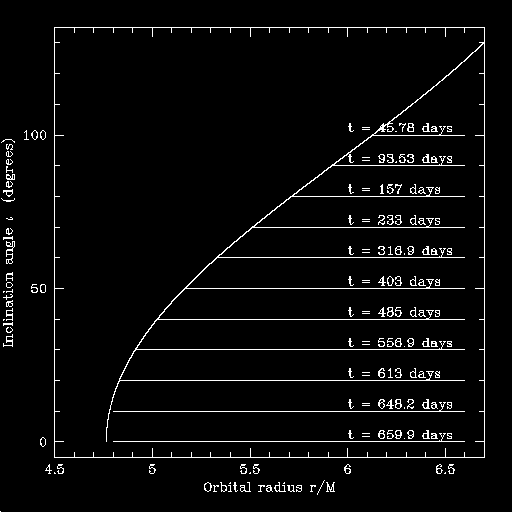

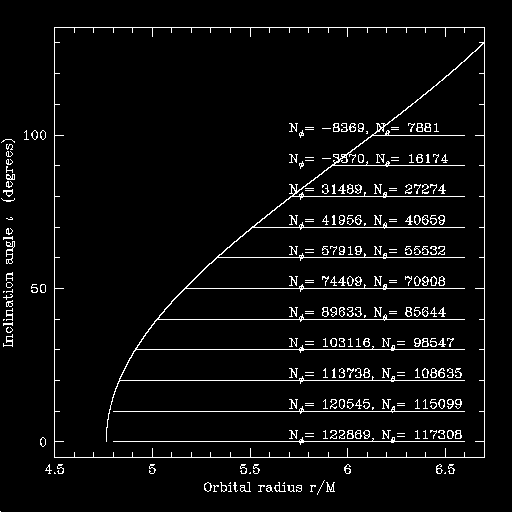

This next plot is essentially the same as that given above, but, in the process of computing the inspiral trajectory, I ignore the radiation that goes ``down the horizon'': evolution in the following plot is driven solely by radiation to infinity:

In contrast to the case a = 0.998 M, the inspiral times do not change very much. This is because the spin choice a = 0.3594 M corresponds to the horizon spin frequency being precisely locked to the orbital frequency of the innermost stable circular orbit. The tidal bulge raised by the inspiraling body does lead or lag the small body by an interesting amount, so it does not exert very much torque on the body's orbit. As a consequence, the horizon has very little influence on the inspiral.

Here are the same plots, parameterized by the number of orbital cycles rather than the inspiral time. First, including the horizon flux:

Second, ignoring the horizon flux:

The change in the number of orbits is likewise extremely small; the fractional change is about 0.07%.

Last modified 13 April 2001.