|

- Zoran Manević - The architectural inheritance of Belgrade is not equally preserved, either according to the date of appearance or to the number of buildings. The course of the history, and a specific geographic situation, with frequent wars and destructions, were not favourable for a longer duration and preservation of the buildings. That is why the most of them dates back only to the 19th century. A little is known about the medieval Belgrade architecture, except about the Belgrade fortress. During the the Turkish government, buildings had all the characteristics of the Islam architecture. Among the public buildings the most abundant were mosques (places of worship), serais (courts), caravan-serais (inns), tekijas (places of dervishes' gathering), medressas (religious schools) and others. As for the residential architecture, it was apparent in individual houses with beautifully arranged gardens. The houses had basements built of stone, a little protruding first floor and a mildly steep roof covered with tiles. With the arrival of foreign specialists after the First and the Second Serbian Insurrections, Belgrade architecture began to obtain western characteristics. During the middle of the 19th century Belgrade experienced a complete urbanistic and architectural transformation. An observer of this phenomenon published in the London "Times" on October the 17th, 1843, a text full of exultations. "Four years have passed since the time when I was last here, and how Belgrade has changed! I have hardly recognised it. Then, it was for three quarters an oriental town. The high belfry on the church (Cathedral) now screens by its shadow the Turkish mosques; many shops are now provided with new doors and glass windows, oriental clothing is more rare and houses with several storeys, in European manner, are being built everywhere".

On this historic path, that placed it among the the European metropolises, Belgrade passed through various stages of urban restoration, obliteration of curved lanes and urbanistically inarticulate fields between mahalas (residential quarters), and setting of right-angled street pattern, frequently at the price of pulling down everything inherited.

At the beginning of the '80s (1881-1884) Bugarski, by order of King Milan, designed and built the palace Old court (present Town parliament). The caryatids, facing the one-time court garden, are the most striking characteristic of the historicistic spirit that reigned in Belgrade and Serbia during the last quarter of the 19th century. Historicism is the basic characteristic of Belgrade architecture also during the first quarter of the present century, even where the intention of the author was to accept different varieties of 'art nouveau', better known here under the Wien name "secession". The most characteristic Belgrade building in the first half of the 20th century is the palace of National Parliament. The first design of the House of national representatives, as the building was formerly called, was made by a Wien architect of Serbian origin, Konstantin A. Jovanović, who also raised at the end of the '80s of the 19th century the best example of neorenaissance, the palatial edifice of National Bank of Serbia, in King Petar street. This Jovanović's design, on a contest in 1901, was somewhat changed by Jovan Ilkić, who after that made plans according to which the construction began, on a deserted field called "Batal-Džamija", in 1907. The construction of National Parliament lasted for three decades. After the death of Jovan Ilkić (1917) the construction was continued according to the plans reconstructed by his son, Pavle Ilkić, and many others participated also in that important work, like a Russian emigrant, academist, Nikola Krasnov and others. Krasnov is the author of two monumental mansions of Belgrade between the two world wars, the buildings of Ministry for foreign affairs and of Government of Serbia at the corners of Nemanjina and Miloš the Great streets. The author of the edifice of General staff in Prince Miloš street is also a Russian emigrant, Vilijam Baumgarten. A number of other mansions designed in academistic spirit were built by Russian emigrants, like the building of Main Post office (Vasilije Androsov), the building of Patriarchy (Viktor Lukomski), the last one with admixtures of neobyzanthium tendencies.

The neobyzanthium (or serbo-byzanthium) style is another form of historicism, well represented in Belgrade architecture. Predecessors of such views were Hansen's students, Svetozar Ivačković (Church of Saint Nikola on New cemetery, 1893) and Jovan Ilkić (House of Saint Sava, later on the building of Teachers' college in Dušanova street, 1890), but the true examples of national historicism are considered to be Tanazović's works, the building of Main telephone exchange in Kosovska street (1908) and the building of Ministry of education (the present Vuk's foundation) in Terazije. New views on the necessity of emphasizing the functionality of a building, as well as an obvious demonstration of characteristics of building materials, iron and reinforced concrete, brought also to Belgrade a desertion of historicism, either its classical, or neoromanticistic form. Already in 1907, a civil engineer, Viktor Azriel, raised a modern department store in 16 King Petar street, the facade of which is a predecessor of, up till recently popular, form of "wall-curtain". In the same year, Nikola Nestorović and Andra Stevanović, the authors of the mansions of Funds management (the present National museum) and Belgrade union, raised their most important work in the spirit of secession - "House with green tiles" at the corner of Uzun-Mirkova and King Petar streets. Early functionalism is present also in the works of Jan Dubovy, of Czech origin, one of the founders of the modern movement. These works emerged as a result of a social programme of Belgrade community (Workers' shelter for men and Children nursery school in Miloš Pocerac street and Workers' shelter for women in Prince Mileta street) and they do not offer any attraction with their unornamented facades. The observatory complex on Zvezdara (1930) is somewhat more famous, also a work of Jan Dubovy. Founders of the modern movement were, beside Jan Dubovy, Milan Zloković, Branislav Kojić and Dušan Babić. At the beginning of the 30s they were accompanied by Dragiša Brašovan, brothers Krstić, Branislav Marinković, Momčilo Belobrk and others. Modernism, founded on postulates of "international style", developed during the 30s a mannerism in which the decorative elements were horizontal furrows between windows, round windows at the top of a building, noticable position of the flag pole. The best examples of Belgrade modernism are completely out of manneristic tendencies. Of those, the first to be mentioned are the works of Milan Zloković (villa of Šterić family in General Šturm street on Dedinje, or the building of Children's hospital on Vračar) or the works of Dragiša Brašovan (the block of flats of the Beočin cement factory in 21 Braće Jugovića street, or the building of BIGZ (Belgrade printing bureau) in Vojvoda Mišić Boulevard). These Zloković's and Brašovan's works may be placed in any review of modern architecture of the world without recognizing of any regional features. The early postwar period is filled with the theory of socialistic realism. The results of these views, imported from the Soviet Union, were figuratively poor buildings of the Faculty of economics, near Railway station, or the building of Trade Union Hall, pavilion-type blocks of flats in Cvijićeva street. During the middle of the 50s, communication with the West and contemporary architectural movements, originaly brought a valorisation of Le Corbusier principles (the building of Military printery in Mija Kovačević street), followed with the best example of structuralism within Belgrade territory, the complex of Fair exhibition halls (Pantović, Krstić, Žeželj, 1954-57).

The middle generation (Aleksandar Đokić, Petar Vulović, Lojanica team of authors, Jovanović, Cagić and others) acted almost simultaneously with the oldest one and thus found itself unjustly in its shaddow. It was only recently that the most significant works of the representatives of this generation (Transformer sub-station "Film Town" by A.Đokić, the building of Government auditing office in Brankova street by P.Vulović, blocks of flats "Julino Brdo" by Lojanica, Jovanović and Cagić) become unavoidable elements of anthology reviews of the contemporary Belgrade architecture.

The youngest generation of Belgrade architects (Branislav Mitrović, Igor Marić, Josip

Pilasanović, Milutin Gec and others) made its appearance at the beginning of the 80s.

Noteworthy works of these authors carry the spirit of postmodern period and their true

evaluation will be possible only when the '80s and '90s years of our century become the

past.

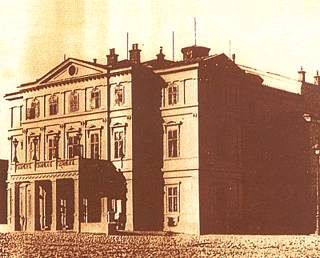

Albania Palace Building | The Bajrakli Mosque | Belgrade Palace Building | Belgrade Railway Station | Captain Miša's Building | Cvijeta Zuzorić Art Pavilion | Karađorđeva Street | Knez Mihailova Street | Princess Ljubica's Residence | Millenary Monunemt on Gardoš Hill | Price Miloš's Residence | The National Theatre | Nemanjina Street | Nikola Pašic Square | Republic Square | Skadarlija | Slavija Square | Student Square | The Trade Union Hall | Terazije Square | The '?' Cafe Restaurant | Article about the architecture and building in Belgrade |

Architecture that has, so far, survived all the wars and destructions, pullings down

and additions, symbollicaly resembles a picture which the English tourist must have had

in front of him. No milieu from the middle of the 19th century is completely preserved,

but the buildings of Dositej's Lycée,

Architecture that has, so far, survived all the wars and destructions, pullings down

and additions, symbollicaly resembles a picture which the English tourist must have had

in front of him. No milieu from the middle of the 19th century is completely preserved,

but the buildings of Dositej's Lycée,  Architecture that emerged on the ruins of the Turkish houses in the Danube part of the

city, on the ruins of the Serbian thatched huts in the Sava part, or on the new ground

between Slavija and the Stamboul Gate on the present Place of Republic, bore, to a

lesser or higher degree, sometimes only in traces, the style characteristics of their

time. It may be hypothesised, although allowing for an insufficient professional education

of that-time baumeisters (builders), Germans, Czechs, Italians, that Belgrade, during

the period of half a century, between 1830 and 1880, came to know the fundamental

characteristics of classicism (building of the Realka secondary school, the west facade

of Cathedral Church), romanticism (Captain Miša's building,

the building of Town hospital in George Washington street, the building of the one-time

Israel Embassy in Captain Miša street), as well as the examples of, then very widespread,

sentimental historicism, like the only so far remained neogothic facade of the building

incorporated into Mitić's department store, in Princ Mihailo street. The Serbian

architects appeared in Belgrade only at the end of the '60s of the last century.

Undoubtedly the most important of them was Aleksandar Bugarski, who, immediately after

the arrival to our country, built the palatial edifice of

Architecture that emerged on the ruins of the Turkish houses in the Danube part of the

city, on the ruins of the Serbian thatched huts in the Sava part, or on the new ground

between Slavija and the Stamboul Gate on the present Place of Republic, bore, to a

lesser or higher degree, sometimes only in traces, the style characteristics of their

time. It may be hypothesised, although allowing for an insufficient professional education

of that-time baumeisters (builders), Germans, Czechs, Italians, that Belgrade, during

the period of half a century, between 1830 and 1880, came to know the fundamental

characteristics of classicism (building of the Realka secondary school, the west facade

of Cathedral Church), romanticism (Captain Miša's building,

the building of Town hospital in George Washington street, the building of the one-time

Israel Embassy in Captain Miša street), as well as the examples of, then very widespread,

sentimental historicism, like the only so far remained neogothic facade of the building

incorporated into Mitić's department store, in Princ Mihailo street. The Serbian

architects appeared in Belgrade only at the end of the '60s of the last century.

Undoubtedly the most important of them was Aleksandar Bugarski, who, immediately after

the arrival to our country, built the palatial edifice of  The oldest generation of the present time, whose still living representatives are Mihailo

Mitrović, Aleksej Brkić, Ivan Antić, formed during the '60s and '70s an awareness of the

worth of Belgrade architecture, both through the materialized works (Museum of the

contemporary art, Sporting center on Dorćol, the building of Serbian police department at

Mostar by Ivan Antić, block of flats in 10-14 Braće Jugovića street, Genex Center in New

Belgrade by Mihailo Mitrović; the building of Social insurance in Nemanjina street by

Aleksej Brkić), and on the pages of the journal "Architecture and urbanism" whose founder

and long-standing editor was Dr Oliver Minić.

The oldest generation of the present time, whose still living representatives are Mihailo

Mitrović, Aleksej Brkić, Ivan Antić, formed during the '60s and '70s an awareness of the

worth of Belgrade architecture, both through the materialized works (Museum of the

contemporary art, Sporting center on Dorćol, the building of Serbian police department at

Mostar by Ivan Antić, block of flats in 10-14 Braće Jugovića street, Genex Center in New

Belgrade by Mihailo Mitrović; the building of Social insurance in Nemanjina street by

Aleksej Brkić), and on the pages of the journal "Architecture and urbanism" whose founder

and long-standing editor was Dr Oliver Minić.