The Long Wharf region of Boston is one of the most storied regions in the entire United States. It forms the beating heart of the city of Boston, prospering with the city, and falling on hard times with city. The site has been shaped by the very modes of transportation that have driven American culture throughout the ages. Originally the site grew as the port of Boston flourished, bringing goods into the burgeoning city. This trend continued until the turn of the twentieth century, when the introduction of the automobile caused the area to decline as a hub of businesses. Then, with post war suburbanization drawing people out of the city, and with commuting on the rise, the site was devastated by the creation of the Central Artery. Today the site has been restored through the construction of the Greenway, creating a much more vibrant public area. Yet the Long Wharf and Faneuil Hall site still have many artifacts and traces of what used to stand, and as the site has developed and evolved throughout history, these artifacts and traces have clumped together into layers that can tell the story of both the area and the greater city of Boston.

. The remains of the Central Artery

. The remains of the Central Artery

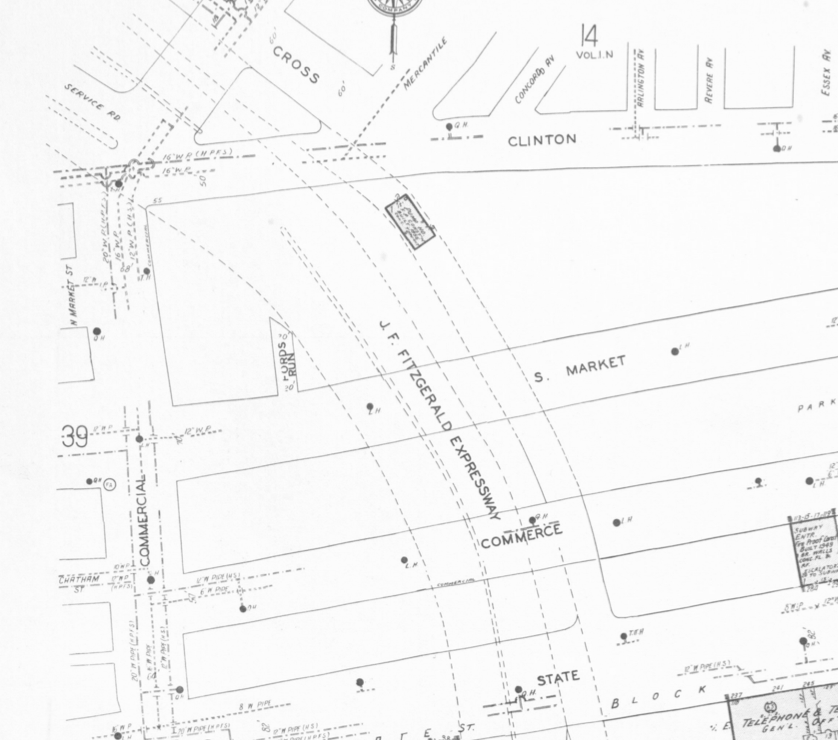

. This is how the area appeared in 1974. The beam is found today in the upper left of the map, near where the Central Artery begins to curve to the West. (courtesy of Sanborn Maps 1974 series)

. This is how the area appeared in 1974. The beam is found today in the upper left of the map, near where the Central Artery begins to curve to the West. (courtesy of Sanborn Maps 1974 series)

Entering into the Quincy Marketplace one can run into this steel beam that juts from the ground, standing over six feet tall. This monolith of iron is all that remains of the most influential structure to the entire site of the twentieth century, a structure that changed the face of the entire area and forced everything to evolve and adapt towards what is seen today. This beam is all that remains of the Central Artery. The Artery was constructed in the 1950s with the boom in suburbanization drawing many out of the city into their own homes. The influx of automobile commuters caused the entire district of the Long Wharf site between the Marketplace and Atlantic Avenue to be torn down. As the Sanborn maps previously looked at demonstrated, it was filled with storage warehouses that had been declining over the past few decades, with more and more simply listed as “storage” as opposed to any company, implying that there was not much use for them. This entire third of the site was lost for the automobile, and yet today such a radical change is only remnant in one single artifact. This highway was initially seen as beneficial, but quickly killed off the businesses in the site. This behavior is very similar to what Spirn observed in the Mill Creek area as she said in the Language of Landscape, “Signs of hope, signs of warning are all around, unseen, unheard, undetected. Most people can no longer read the signs: whether they live in a floodplain, whether they are rebuilding an urban neighborhood or planting the seeds of its destruction” (11). People rarely think that they will hurt the area if they build an improvement, but there are always unseen consequences. The beam at the corner of the Quincy Marketplace has all of this history wrapped inside of it, a simple piece of metal that stands for such a radical shift in the area, and such a huge oversight of the power people have on their surroundings.

. The rear doors of the Quincy Marketplace, left over from its days as a storage facility

. The rear doors of the Quincy Marketplace, left over from its days as a storage facility

. The door of one of the original businesses in the Marketplace, next to a modern day bar

. The door of one of the original businesses in the Marketplace, next to a modern day bar

. This map shows the Quincy Marketplace in 1867. Every shop space is filled with different commercial enterprizes or businesses, and some even have been named on the map (courtesy of Sanborn Maps 1867 series)

. This map shows the Quincy Marketplace in 1867. Every shop space is filled with different commercial enterprizes or businesses, and some even have been named on the map (courtesy of Sanborn Maps 1867 series)

Immediately next to this beam is Clinton Street, which runs behind the north row of shops in the Quincy Marketplace. As one walks down this street, it becomes very clear that nearly all of the shop back doors are the same. These doors are all very old and most are painted green. Then there are others that are even older and bear the signs for the original businesses that stood behind them. These both are the remnants of a time over a hundred years ago when the Marketplace was a much different scene than it is today. The red door with the iron sign seen above dates from the creation of the Quincy Marketplace in the 1860s. Back then, the Marketplace was predominantly owned by individual shopkeepers who all ran unique businesses out of the storefronts that the site provided. It served as the retail and service center of downtown Boston. The Sanborn maps previously analyzed show that nearly every different kind of industry imaginable was in place in the site, and so Bostonians could do anything and everything that they needed to do in the Quincy Marketplace. Then, as the nineteenth century turned into the twentieth, the area began to slump. The shops left and by the 1920s almost all of the Quincy Marketplace had become storage warehouses for the companies that ran storage around the Long Wharf area

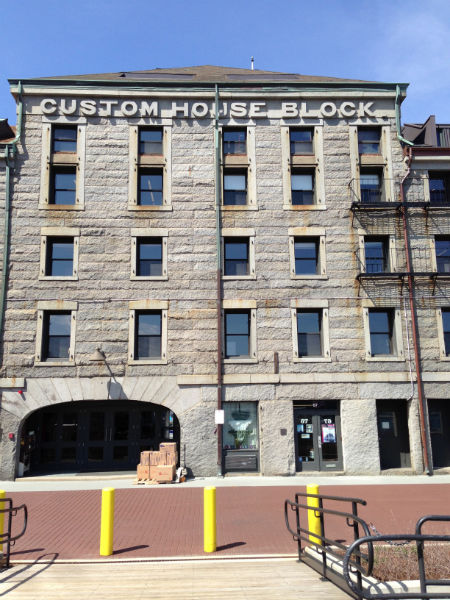

. The Custom Block House as it stand today at the end of the Wharf

. The Custom Block House as it stand today at the end of the Wharf

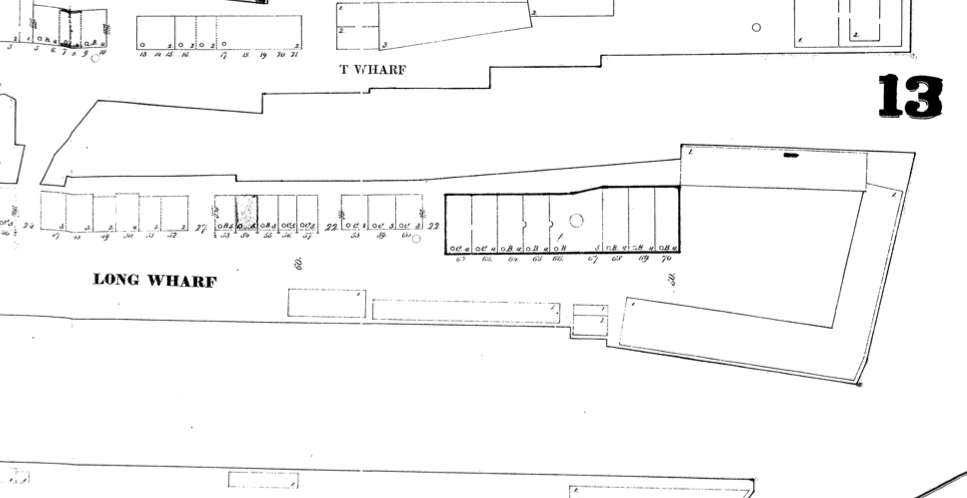

. This is a Sanborn map from 1867, and the Customs House Block is the building outlined in bold at the end of the wharf. By 1970, it will be one of only two remaining structures on the wharf (courtesy of Sanborn Maps 1867 series)

. This is a Sanborn map from 1867, and the Customs House Block is the building outlined in bold at the end of the wharf. By 1970, it will be one of only two remaining structures on the wharf (courtesy of Sanborn Maps 1867 series)

Walking out onto the Long Wharf, one can find that a large imposing gray stone building sitting at the end of the wharf with big bold letters engraved into the top spelling out CUSTOM HOUSE BLOCK. This building is what remains of the bustling shipping industry that used to come through the Long Wharf and to all of Boston. Looking at the Sanborn maps, this building is one of only two on the entire Long Wharf that have survived to this day, being built some time before even 1867 to serve as a Customs House office. Looking through all of the different uses of the first floor, it appears that the Wharf has been in a steady decline since the turn of the century, with the Customs office selling it as a warehouse with a shop or two in the early twentieth century. Today it stands mostly boarded up as a warehouse, with one of two boat tour offices open out of the numerous doorways into the building. This building is a testament to the former strength of the sipping industry in the Long Wharf area. What had once been a bustling port today is a quiet place with a few offices and a public space for people to enjoy a beautiful day. This building has had great difficulty adapting to the changes in the site due to new methods of transportation, but somehow it has managed to survive to today.

. The Chart House, a building older than our nation that today has been renovated into a steakhouse

. The Chart House, a building older than our nation that today has been renovated into a steakhouse

Returning towards shore, it is nearly impossible to miss the Chart House standing next to the Customs Block House. Built originally as an office for a shipping company, the Chart House building continued to be used as an office for over a hundred years until the late nineteenth century. At that time the building, along with all others on the Long Wharf, was converted into a storage warehouse for the influx of goods coming into Boston. This was most likely done out of necessity, as this is the time when the site saw a significant growth in warehouses and the construction of the Atlantic Avenue railway. The traces of this period can be seen on the building, with the windows and doors on the lower level restored after the structure was converted into a steakhouse in the 1980s as the area opened up to more public use. The steakhouse has taken many painstaking moves to restore the Chart House to how it must have appeared in Colonial times when it was first constructed, touting itself as formerly owned by John Hancock, and attempting to remove any signs of its time as a storage warehouse. The interior, however, is completely different, as the building is now a steakhouse. Everything has been renovated to modern standards, and no semblance of the former offices can be found. Despite this, the building still stands at the confluence of history like most of the site. When one walks in to enjoy the steakhouse, you can run the risk of hitting your head on the same brick arches that John Hancock must have hit, all while enjoying a Patriots game. It is this convergence of past and present that so succinctly defines the site.

. The Marriott from across the Greenway

. The Marriott from across the Greenway

. notice the similarity in shape between the Marriott and this warehouse a few blocks away

. notice the similarity in shape between the Marriott and this warehouse a few blocks away

At the point where the Long Wharf rejoins the mainland lies the Marriott Hotel. Built in the 1980s as the site became much more open as a public space, the hotel is one of the newest buildings in the entire Long Wharf site. On the location it was built originally sat a series of warehouses used by the shipping industry, but those were torn down with the construction of the Central Artery and replaced with a parking lot. But the Marriott Hotel still has some very strong connections to the past. If one compares the structure of the hotel to warehouses on nearby wharves, it becomes abundantly clear that the design of the building is modeled after the structure of the wharf warehouses. This nod to the past is the link between what had stood on the site for a hundred years and what is there today. This is a radical change from how things are normally done in a city, and a very powerful sign of the influence that the past and the sea have on the makeup of the site. As Spirn told us in the Language of Landscape, “Planners' maps show no buried rivers, no flowing, just streets, lines of ownership, and proposals for future use, as if past were not present, as if the city were merely a human construct not a living, changing landscape” (11). The trace of the shipping industry really demonstrates the importance of the harbor to the site and especially the Wharf area, as was discussed in assignment 2. This connection to the sea permeates all of history, and is the constant tie that binds all of the history of the site together.

The layers of history might not always be able to build upon one another, but they still find a way to permeate through history and tie different periods together. In the Long Wharf, this tie throughout all of history is the power of the sea, and its ability to influence the businesses of the site. This draw of the sea manifests itself in many ways, be it the offices and customs houses that built up around the vibrant shipping business, or simply through the hotel that springs up to take advantage of the sea. This is the true character of the Long Wharf site. The buildings of the wharf just analyzed are a great example of this. The layers of time have built them up, three buildings, two originally meant to aid with the shipping business that have developed along different paths, and one that was only recently built but still influenced by the site. Three buildings all influenced by the harbor right next to them; the harbor that has been subtly pushing their development throughout time.

. The Greenway facing the buildings of State Street. Notice how this building does not open onto the Greenway at all

. The Greenway facing the buildings of State Street. Notice how this building does not open onto the Greenway at all

In between the two areas previously looked at lies the Greenway. The Greenway is a very obvious trace of the Central Artery, which cut right through the heart of the city and was replaced by the Greenway, but it also serves as a reveals much more than just the course of a road. If one looks at the buildings that border the Greenway, it becomes evident that the Central Artery affected the way that these buildings were constructed. Many, like the one seen in the picture above, that were built before the Central Artery was torn down, have directed their entrances and lobbies away from the Greenway. Instead, the backs of these buildings have large blank walls facing what used to be a major highway, showing the distain people had for the Artery, but also how people adapted to it. The Artery becomes more than just a mark of what used to be here, but it serves to emphasize the effect that it had on the surrounding community.

. The newest stores in the Quincy Marketplace have the rear of the buildings, including loading bays, facing the Greenway, as if they do not want to interact with it

. The newest stores in the Quincy Marketplace have the rear of the buildings, including loading bays, facing the Greenway, as if they do not want to interact with it

Looking at one end of the Greenway, one can find the back of the storefronts that were built for the Quincy Marketplace during the late 1970s and early 1980s. The signs of the effects of the Central Artery is very clear in the loading bay doors for all of the shops. Every single one of them faces out towards the Greenway. There are not even any windows on these buildings to face the Greenway, when the other side towards the market is almost entirely glass windows. This is a trace of the Central Artery and how it created a desolate tract of land underneath it that was completely under used. To anyone who is not familiar with the history of the site, one would think that the shops were foolishly shunning the Greenway, when in reality they had built their stores in a reasonable manner to divert the shop fronts away from the underside of highway overpasses. This trace of the history of the Central Artery is clear to anyone who looks, and is a testament to exactly how much the highway influenced the site.

. The image captures the spirit of the site, with the old and new juxtaposed together and constantly growing

The Long Wharf and Faneuil Hall site is clearly one with a lot of history, but the real story behind it is exactly how clearly that history is shown today. Just by looking at the buildings of the site, one can begin to see the true spirit of the area and of Boston as a whole, with the old and historically significant standing right next to the modern and new structures that have been built. Sometimes these buildings are renovated with a modern segment or interior as we have seen. Others are Historical buildings that have had residents move in and out until they have evolved into something completely different from the initial design of the building. And still others are brand new structures, standing with some way to recognize the past and how it has shaped it. Yet all of these layers coexist together, and that is the real beauty of the Long Wharf site, the old and new juxtaposed together into the modern world.

Works Cited

Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Language of Landscape. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1998. Print.

Fire Insurance Maps from the Sanborn Map Company Archives Late 19th Century to 1990. Map. New York: Sanborn Map & Pub., 1867. Print.

Fire Insurance Maps from the Sanborn Map Company Archives Late 19th Century to 1990. Map. New York: Sanborn Map & Pub., 1974. Print.