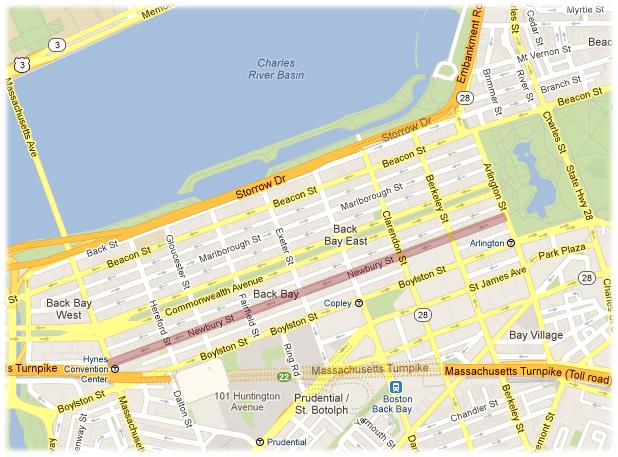

Location of Newbury Street within Boston. Source: Google. Google Maps (2013). Retrieved from http://maps.google.com.

Location of Newbury Street within Boston. Source: Google. Google Maps (2013). Retrieved from http://maps.google.com.

Today a shopper walking down Newbury Street would never guess that it was built on filled land. There are little to no signs of Newbury Street’s pre-19th century past, when the Back Bay was merely water. In the mid-19th century, however, under the pressure of a booming population and the restrictions in land space, landfill operations efficiently expanded the small Boston peninsula outward to accommodate more residential neighborhoods. In a Herculean planning and engineering feat, the Back Bay was filled at a rate of almost two house lots per day for nearly forty years. Thus Newbury Street was formed as part of the grid, originally intended as another residential neighborhood. [1]

The origins of Newbury Street are a telling tale. The neighborhood was motivated by the need to overcome not conform to the natural environment. And as I walked down the street from Massachusetts Avenue to Boston Commons, I found patterns within the details of the building layouts, in the plant life, and in the sidewalks that were a result of such motivations. From my perspective, I unearthed the following story: when Newbury Street was first constructed, its design paid attention to the foundational soil but did not account for other natural processes, but over the years the street has been “retrofitted” to respond to the resulting conflicts between city and nature.

Newbury Street’s foundations make for a unique relationship between city and soil. Knowing that Newbury Street was built on filled land, I immediately began searching for signs of unstable soils or cracking foundations. [2] Unfortunately, because of the accumulation of snow that had not yet fully melted, couple with the fences that surrounded many of the building foundations, I was unable to observe the buildings too closely. During the chances that I did have to peer at the bottoms of the buildings, I was surprised to find no abnormalities: no cracking or warping. Of course, nearly all the buildings were built from brick or stone, which are more resistant to the natural elements than wood or other more malleable building materials.

Different building materials: brick and stone

Different building materials: brick and stone

Unable to find conflicts between city and soil in the building foundations, I moved my attention to the sidewalks and roads. The sidewalks, in particular, were riddled with cracks, holes, and missing pieces and looked like they had not been properly maintained. Initially within the first segment of Newbury Street, extending from Massachusetts Avenue to Fairfield Street, it was difficult to identify the cause of the cracking patterns in the granite, other than the wear of pedestrians. Farther down Newbury Street, however, closer to Boston Commons, there were noticeable uneven areas in the sidewalks, where two or three converging stone panels were misaligned, the effect being that one panel would be higher than another. These disjointed sidewalk segments seemed more likely to have been a cause of the uneven settling of filled land beneath. (Unfortunately, I’m missing a photo depiction of this phenomenon.)

This observation provides an interesting point of speculation. Because Newbury Street was built over the course of four decades, beginning from the Commons, it is possible that the filled land near Boston Commons has had more time to settle than the filled land closer to Massachusetts Avenue. It is also possible that the filled land near the avenue is more structurally sound because it was built later in the century, after several more decades of experience and improved technology.

Despite small disjointed segments of sidewalk, however, I was impressed by the absence of significant conflicts between the city and its foundational soil. This fairly pervasive absence in fact makes quite a lot of sense. When the Back Bay was being filled in, foundational soil would have required extra attention to ensure the structural integrity necessary to support entire neighborhoods.

From my initial observations of city and soil, I began to formulate a picture of Newbury Street that was in harmony with its natural processes. I began applauding the engineers and city planners for their attention to nature in their design. But very quickly, this view reversed as I began to observe the relationship of the city to the other elements of nature, particularly its relationship to water.

The interaction between water flow and Newbury Street’s design is perhaps most interesting. Aside from the small fissures in the sidewalks near Massachusetts Avenue, I also immediately noticed more glaring cracks running along, in what seemed to be like, no identifiable pattern. One of the very first photos I took (below) shows a large crack running between the gaps of the sidewalk panels and the gutter.

A crack running between the gaps in the sidewalk and the gutter

A crack running between the gaps in the sidewalk and the gutter

Initially and naively, I thought the crack had propagated from the gutter, perhaps caused by the way the gutter had been inlaid into the surrounding stone. I found these cracks all over Newbury Street. Fortunately, because the snow hadn’t melted thoroughly, I was able to observe the water flow patterns along the sidewalks, and I quickly realized the cracks were caused by erosion from running water.

Water flow patterns along the crevices of sidewalk panels

Water flow patterns along the crevices of sidewalk panels

Resultant erosion patterns

Resultant erosion patterns

The image above on the top was my first clue to the aforementioned insight. The water flowing from the melting snow pile ran almost strictly between the gaps of the stone panels and down toward the streets. The water trace helped me explain the erosion patterns along the edges of other sidewalk panels. In the image on the bottom, the worn edges were clearly also from the erosion of precipitate following the maze of gaps downhill. These observations made it quite apparent that in my original photo above, the crack had not propagated away from the gutter but rather down the crevices of the sidewalk panels, through the stone, and toward the gutter.

As I became increasingly attuned to these erosion patterns, I found myself looking at a map of the water flow through Newbury Street. One of the most unique examples of this concept came from the erosion pattern on a brick path. As I was walking by a shop, I noticed a path of crevices between the bricks, slightly darker and wider than the rest of the crevices, along the middle of the walkway to the shop’s entrance. After taking a closer look, I realized the darkened path had been created by the erosion of the bricks, which, as a result, had left an impression that carefully traced out the path most often taken by a stream of water trickling from the steps to the curb.

The path of water flow etched into brick path from erosion

The path of water flow etched into brick path from erosion

The discovery of these “water maps” etched in the sidewalks led me to several more insights. First, I realized that all the sidewalks were purposefully sloped toward the streets to guide runoff away from the buildings. Based on the relatively younger age of the sidewalks as compared to the buildings, it seemed that the sidewalks had not been designed with said slope originally but rather had been altered during later renovations, because many of the sidewalks sloped unnaturally and unevenly.

An example of the unevenness and "lumpiness" of the slope in the sidewalk

An example of the unevenness and "lumpiness" of the slope in the sidewalk

Second, the placement of many of the gutters did not align with the water’s natural flow patterns. For one, most of the gutters were placed in the middle of sidewalk panels when the water clearly flowed most often along the edges of the panels. This improper placement led to the most severe crack formations within the panels, caused by the water cutting through the stone to the gutter. Even worse, some gutters were placed on patches of sidewalk that were in fact uphill from the water. Although it is difficult to see in the picture on the far bottom, in this particular case, the drain sits atop a slightly elevated section of the sidewalk, making it completely ineffective for draining the surrounding water and snow.

Poor placement of these gutters result in cracked sidewalks and ineffective draining

Poor placement of these gutters result in cracked sidewalks and ineffective draining

Third, Newbury Street received a lot of precipitation, apparent from the amount of erosion on the sidewalks and roads. These three insights culminated in a larger realization of the relationship between city and water.

Newbury Street was not at all built with attention to the patterns of rainfall and water flow. Most obviously, Newbury Street houses many stores within the basements of buildings. Based on my third observation that Newbury Street experiences a high volume of rainfall, this design seems unwise and counterintuitive. Furthermore, filled land is already quite low compared to see level and in danger of flooding, making underground designs even more susceptible to water damage. [3] During my observation, I found several corrective measures that had been taken to compensate for this poor design. For example, at the bottoms of many of the staircases leading to an entrance below street level, one or more small drains have been added to decrease the potential impact of water accumulation.

A small drain between the base of the staircase and the entrance

A small drain between the base of the staircase and the entrance

In general, Newbury Street also has a higher density of gutters riddling than sidewalks than a typical street in Boston. Oftentimes a gutter will be placed on the wrong side of a slope and be significantly less effective for intercepting the natural path of water flow. The high volume of gutters and lack of strategic placement again suggest that these gutters were not part of the original design but added as corrective measures. The uneven sloping of the sidewalks gives yet another example of the need to overcome the original design flaws in relation to water.

The consequences of this discord between city and water are evidenced by the resultant severe erosion around gutters, following the edges of sidewalks, and on the streets. The streets in particular suffer from the high volume of runoff that is dumped onto its concrete as redirected by the crooked sidewalks. The image below shows a good example of the extreme damage suffered by the concrete particularly around the gutters.

The concrete around street gutters suffer a severe amount of erosion damage from the high volume of runoff that is dumped onto the streets from the sidewalks.

The concrete around street gutters suffer a severe amount of erosion damage from the high volume of runoff that is dumped onto the streets from the sidewalks.

Not only are these consequences visually displeasing, they also have large economic implications. To repair and maintain such damage requires a substantial and continuous flow of money. These conclusions bring to light the importance of paying attention to natural processes in good urban design.

On my final walk through Newbury Street, I paid special attention to the plants on Newbury Street. Surprisingly, I did not notice any wild plants along the streets or the sidewalks. I could not tell if the lack of wild plants was caused by Boston’s biting winter, by intentional city maintenance, or by hostile conditions, but every form of plant life that I could observe had been purposely planted. And it was clear not a very nurturing environment for life.

Of all the trees that lined the sidewalk, I could count on one hand the number that had reached maturity, around forty years of age. [4] Most of the trees were planted in squares of soil no larger than four square feet with barely any room for growth. From the relative ages of the trees, it was also apparent that many of them had been planted within the decade, indicating a rapid turnover and poor survival rate of the trees that had been replaced. It was also a common sight to see a scrawny tree flanked on either side up by supporting wooden poles with thicker circumferences than the tree trunk itself.

The poor conditions under which street trees must survive

The poor conditions under which street trees must survive

In addition to the poor soil condition, the trees on Newbury Street were also grappling with other conditions not within their favor, as in common with all city plants, including limited sunlight, polluted air, and large fluctuations in water quantity. [5] I performed my observations in the early afternoon, between 2:30 and 4:00 PM, when the sun was around its highest point in the sky. This gave me a unique opportunity to observe the role of sunlight in the city plants’ lives. As shown in the image above, depending on the height of the buildings immediately surrounding a tree, a tree could either receive a good deal of sunshine, or in this case, very limited amounts of light. The density of the buildings and narrowness of the streets also affect light exposure. Closer to the Commons, Newbury Street is much wider and less dense in building population; as a result, any larger trees that I observed tended to line the segment of Newbury closer to the Commons.

In certain cases, the snow accumulation also showed the relationship between the trees and water. In the photo depicted below, it is evident that the tree is not benefitting from the large volume of snow pile around its base. And although I can only speculate, it seems like this kind of conflicting relationship is equally as if not more common than a nurturing relationship. Not only would this conflict arise in the quantity of water, but it could also manifest in the quality of water. Because the trees are planted on the downward sloping edges of the sidewalk, runoff washing down the pavement would pick up any pollutants from the ground, and feed it directly to a thirsty tree.

A scrawny tree fights the force of the snow.

A scrawny tree fights the force of the snow.

Aside from the street trees, different stores and restaurants also planted their own shrubbery to decorate their storefronts. As we talked about in class, the contrast between the scrawny street trees and the meticulously groomed storefront trees provided a perfect depiction of the differing relationships people can have with plants. Storefront trees were also more common among the regions of Newbury close to the Commons, indicative of the economic transition. Again, this provides insight into the economic burden of maintaining city plants under such hostile conditions.

Plants lining storefronts are far better maintained than street trees.

Plants lining storefronts are far better maintained than street trees.

Plant life is an essential part of a city. As Professor Spirn writes in her book, they are the “lungs for the city,” filtering out pollutants and enhancing air quality. [6] Along Newbury, however, the trees are planted in an environment that did not account for plant life in its design. But it is clear that the city has tried to fight this hostile environment, persistently replacing trees to maintain a decorative quality along the street. Had city planners been more attentive to the importance of city plants and their needs, however, the street could have been designed in a more accommodating manner, including larger strips of soil, maximized sun exposure, and strategic placement for improved access to clean water.

Newbury Street was motivated by the need for more residential houses. Thus, when it was built, city planners and engineers paid attention to the structural integrity of the foundations and the efficiency of the building process. Unfortunately, they cast aside regard for the city’s relationship to other important natural processes, including water flow and plant life. In certain places, carefully instigated corrective measures have proved effective in compensating for the water-intolerant design, for example, the small drains strategically placed in front of the entrances to basement stores. In other places, by chance, the building heights and street widths are more accommodating to plant life in the immediate area. But the planners’ initial disregard has led to major tangible and intangible consequences, including the glaring erosion damage on the roads and on the sidewalks, the somewhat pathetic presence of trees struggling for survival, and the economic burden of repairing the water damage and maintaining the plant life.

The case study of Newbury Street is not limited to only this street, but rather brings attention to much more pervasive issues in city design and planning. All too often, cities are regarded as opponents to nature; they are built to overcome nature’s limitations. But this is not the healthiest and most successful approach, as evidenced by the consequences such a mindset may bring. Instead, the city should be viewed as an extension of nature; only then can city and nature flourish alongside each other and mutually benefit each other.

[1] Anne Whiston Spirn, The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design (United States: Basic Books, 1984), 18.

[2] Spirn, 19.

[3] Spirn, 19.

[4] Spirn, 171.

[5] Sprin, 175.

[6] Spirn, 172.