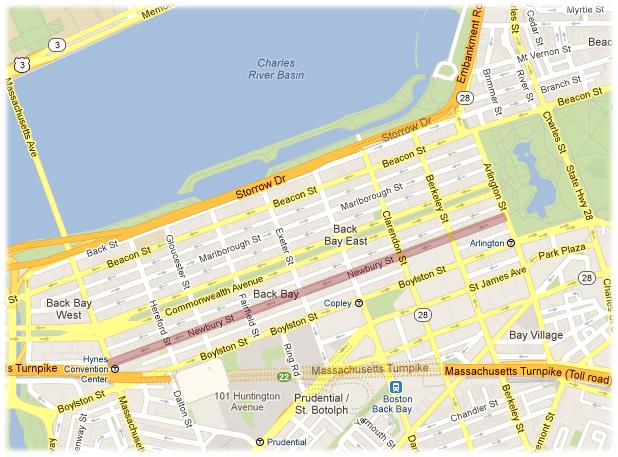

Location of Newbury Street within Boston. Source: Google. Google Maps (2013). Retrieved from http://maps.google.com.

Location of Newbury Street within Boston. Source: Google. Google Maps (2013). Retrieved from http://maps.google.com.

Today the characteristic brownstone stores and cafes of Newbury Street provide a delightful and unique personality to this commercial attraction. They beckon shoppers and foodies alike with a welcoming and homey feel, setting Newbury Street apart from a more stereotypical city mall or shopping center. To a keen observer, it is apparent that these brownstones were once homes, and this commercial street was once a residential neighborhood. But the story of the repurposing of Newbury Street is much richer than the storefronts tell. The steadfast presence of the brownstones since they were first built in the mid-19th century largely contrasts the fickle nature of their use. Driven by the fashions of the decade, the repurposing of Newbury Street not only tells the story of Boston’s cultural and technological transition but also the story of America’s growth and development as a nation.

The construction of Newbury Street beginning in the mid-19th century coincided with a dramatic shift in the layout of the American city, which largely influenced the street’s purpose and design. Between 1815 and 1875, the rise of new forms of transportation and the rapid growth of city populations began turning America’s largest cities “inside out.” Pre-19th century, houses occupied the city center to maintain easy walking accessibility. But with the invention of the omnibus, horsecar, and railroads, affluent families that could afford the luxury of transportation also gained the luxury of living at the city’s outskirts, away from the grimier city center. This shift gave rise to an “increasing status of the peripheral home.” [1] Thus when the Back Bay was constructed at the periphery of the city, it was purposed as an affluent residential segment.

The choice of the brownstones also mirrors the developing ideals for family life in American society around the same time. The rise in commercialization and rapid expansion of the city led to an increased emphasis on individual privacy, family, and home. Sermons and articles glorified homes as a “moral safeguard” from society, and the single-family home became a symbol of moral rectitude and success. [2] The increasing importance for individual and family privacy also led to an increasing demand for more intricate layouts within homes to accommodate for more personal rooms. [3] These influences were well-reflected within the designs of the brownstones. [4]

With such enticing characteristics, Newbury Street (along with the rest of the Back Bay), was quick to attract wealthy families. An 1897 map of Newbury Street shows that nearly all the brownstones were single-family homes and very few were flats, or multi-family residences. In addition, of the few commercial businesses present, two were liveries and one was a stable for carriages and horses. The relatively large size of these businesses also indicated how important they were to Newbury Street’s residence. All these characteristics underscore the fact that Newbury Street was mainly occupied by families that could afford four-story houses, keep servants, and ride carriages.

Interestingly, several religious and academic institutions, including MIT, also occupied Newbury Street. One can speculate that these institutions chose to occupy Newbury Street to capitalize on its upper middle class “ambience,” or perhaps their presence suggests a relationship between education and social status. [5] Regardless, the presence of such respectable institutions reinforces the image of Newbury Street as a well-to-do neighborhood.

By the teens of the 20th century, however, the fashions of the rich had changed and they moved out of the Back SBay. It is not entirely clear what the reason was, but a 1914 map (Appendix B) of the neighborhood shows the disappearance its liveries and the appearance of a few more flats and three MIT fraternities, a clear indication that Newbury Street had depreciated in property value. [6]

The 1914 map also saw the firsts of Newbury Street’s commercial development and the lasts of MIT’s presence. Even in the 1897 map, it was evident that Newbury Street was already development into an attractive place for tourists from the presence of several street corner hotels clustered near Boston Common that had been refashioned from the spacious brownstone domiciles. These included The Arlington at the corner of Arlington Street, Hotel Kempton at the corner of Berkley, Hotel Guilford at the corner of Clarendon, as well as Hotel Aubury and the largest one Hotel Victoria at the corner of Dartmouth. [7]

Surprisingly, however, the commercial venues that emerged in the 1910s other than hotels were in fact not targeted at tourists but rather at residents. For example, several home improvement stores cropped up, including two upholsters, an interior decorator, and painting services within the two blocks between Arlington and Clarendon streets. There were also tailor shops, libraries, several artistic venues, including an art gallery and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and even the appearance of the Fenway Hospital between Hereford and Gloucester streets. [8] As for the fate of MIT, after it moved across the river, its original building became a part of Boston University before it was completely rebuilt in the mid-20th century. [9] Newbury Street had become home to the new and rising middle class of merchants, shopkeepers, artists, and doctors. [10]

The most dramatic change, however, occurred in the block between Hereford Street and Massachusetts Avenue, driven (no put intended) by the rising popularity of the automobile. Although the automobile had already been invented by the late 19th century in Europe, its high expense and the lack of gas stations, service facilities, and highways prevented it from immediate popularity in America. [11] But in the early 1900s, believing in the utilitarian nature of the motor vehicle, Ransom E. Olds began assembling a very simple model that would be cheap enough for the average American family. As a result of his efforts, one in every eight people had a “motor vehicle” by 1913. [12]

This rapid transition into a new form of transportation completely transformed the block of Newbury Street right next to Massachusetts Avenue. The Charles Gate stable present in 1897 at the corner of Massachusetts Avenue, rendered obsolete, was replaced with an Auto Repairing Shop. One of the liveries at the corner of Hereford Street was also replaced with a garage. Between the two, there were also four additional garages, an auto repairs and sales shop, and a second-hand auto dealer on the block. [13] The presence of a second-hand auto dealer provides further material for speculation; what drove the market behind second-hand automobiles? Perhaps as the automobile became more and more commonplace, it also began to symbolize wealth and status, so much so that even families that could not afford brand new automobiles at least wanted a second-hand one. Despite the shift to the automobile, however, Newbury Street was not widened to accommodate that change. Today the street is still one-way and the main form of transportation is still by foot.

Other technological innovations also made their appearance on Newbury Street during this time. Also within the transportation sector, a new concrete subway was added underground, diagonally intersecting Massachusetts Avenue and Boylston Street, to run nearly parallel to an aboveground railroad line that had been put in prior to 1897. [14] By 1918, it had completely replaced the Boston railroad, which was forced to declare bankruptcy for never making profit. [15]In communication, a brownstone on the block between Exeter and Fairfield streets was repurposed as the Back Bay telephone station. In architecture, a new building built in 1908 had steel frames and concrete floors. [16]

By 1951 (Appendix C), post-World War II, Newbury Street had almost completely transformed into a commercial neighborhood of shops and private institutions. Prior to the war, rapidly improving means of transportation gave families the affordance to relocate their homes to the city’s suburbs. Then during the war, both government and industry fed into the ideal of suburban homes. [17] These factors, coupled with the growth of the city itself, most likely catalyzed the transition of Newbury Street from its residential origins to a commercial attraction.

There are no detailed maps of the progression of commercialization between 1914 and 1951, but certain details on the 1951 Sanborn map provide some insight. It seems that Newbury Street did suffer from the Great Depression for a while, as evidenced by the disappearance of several religious institutions and all of the hotels except for the Ritz Carlton Hotel, occupying what was once The Arlington. By the early 40s, however, it seems that Newbury Street was already on its way to pulling out of the Great Depression, with the construction of the New England Mutual Life Insurance Company in 1940, the largest building within the neighborhood, which occupied well over half the block between Clarendon and Berkley streets, over the location of the original two MIT buildings.

By the 50s, the neighborhood was already back in full swing, home to dressmakers, caterers, photography shops, and painting services. The three blocks between Exeter and Hereford streets stayed largely residential, but with a completely new look. Perhaps another reflection of the Great Depression or the increasing city population, nearly all the brownstones, which had once been domiciles, were converted into apartments or rooming rentals, buildings owned by single families with ten or more rooms rented out for housing. [18]

At the height of the Baby Boom, the 1950s also saw a huge increase in the number of schools occupying Newbury Street. [19] Ten schools spanned the neighborhood, including four private schools, two arts academies, a music school, and a nursing school, all operating out of repurposed brownstones. In fact, the Headquarters Office of the Massachusetts State Board of Education also relocated to the corner of Exeter Street. The influx of so many academic institutions, particularly primary and secondary schools, tried to satisfy the increasing demand for education for the rapidly growing new generation. [20]

Finally, the 1951 map shows several major architectural changes. Buildings built post-1925 were nearly all fireproof, a reflection of the advancement of construction technology; these included banks, garages, and newer apartment buildings or stores. There was also a prevalent trend to add skylights to existing buildings, which riddled the tops of most commercially-purposed brownstones.

Since then, the development of Newbury Street has been a story of continual commercialization, staying aloft the architectural, social and commercial fashions.

Today Newbury Street is one of Boston’s main tourist attractions. With its original brownstones still standing, it is a collision of historic and modern day fashion trends. Although the street has stayed home to the commercial and academic, they have changed over the years to better reflect the different demands of the 21st century. Modern day stores and cafes have replaced dressmakers and caterers. Several smaller banks spanning the neighborhood have replaced the original giant New England Mutual Life Insurance Company, and the large building once home to that company now holds several fashion venues, including H&M, Guess, Sunglass Hut, and Victoria’s Secret. The primary and secondary schools of the Baby Boom have also been replaced by higher education institutes, including Gibb’s College, Boston School of Fashion and Design, and Boston Architectural College. [21]

Newbury Street’s niche in the fashion industry has also led to an uncanny prevalence of salons. Twenty three salons line the street and compete for customers, making Newbury Street almost a mecca for the industry. [22] It is a well-known fact among the profession in Boston that if you don’t make it to Newbury Street, you are no longer in style.

Beginning originally as single-family homes for the wealthy, the brownstones so characteristic of Newbury Street were repurposed again and again, driven by emerging ideals, technological innovation, and trending fashions. This rich, complex social and cultural history is what has made this commercial hotspot much more than a place for food and fashion. Newbury Street has evolved into an iconic symbol of family, innovation, culture, and fashion. It has become the symbol of American growth and a symbol of American wealth.

[1] Kenneth Jackson, The Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 23.

[2] Jackson, The Crabgrass Frontier, 47, 50.

[3] Jackson, The Crabgrass Frontier, 48.

[4] Boston 1895-1900, 1897 [map], 1897, scale not given, “Digital Sanborn Maps 1867-1970,” ProQuest, http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000008.htm?CCSI=254n, sheet 7, 9, 37, 39 (12 March 2013).

[5] Jackson, The Crabgrass Frontier, 27.

[6] Boston 1908-1938, 1914 [map], 1914, scale not given, “Digital Sanborn Maps 1867-1970,” ProQuest, http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000019.htm?CCSI=254n, sheet 7, 9, 37, 39 (12 March 2013).

[7] Boston 1895-1900, 1897 [map].

[8] Boston 1908-1938, 1914 [map].

[9] Boston 1929-1951, 1951 [map], 1951, scale not given, “Digital Sanborn Maps 1867-1970,” ProQuest, http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n, sheet 209, 210, 211, 212, 220, 222 (12 March 2013).

[10] Jackson, The Crabgrass Frontier, 27.

[11] Jackson, The Crabgrass Frontier, 158.

[12] Jackson, The Crabgrass Frontier, 159.

[13] Boston 1908-1938, 1914 [map].

[14] Boston 1895-1900, 1897 [map].

[15] Jackson, The Crabgrass Frontier, 168-9.

[16] Boston 1908-1938, 1914 [map].

[17] Jackson, The Crabgrass Frontier, 232; Boston1929-1951, 1951 [map].

[18] Boston 1929-1951, 1951 [map].

[19] Jackson, The Crabgrass Frontier, 232.

[20] Boston 1929-1951, 1951 [map].

[21] “Newbury Street, Boston, MA,” Map, Google Maps, Google, 5 April 2013, web, 5 April 2013.

[22] “Newbury Street, Boston, MA,” Map, Google Maps.

Maps of Newbury Street in 1897. Click on each image to enlarge.

Source: Boston1895-1900, 1897 [map]. 1897. Scale not given. “Digital Sanborn Maps 1867-1970.” ProQuest. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000008.htm?CCSI=254n, sheet 7, 9, 37, 39 (12 March 2013).

Maps of Newbury Street in 1914. Click on each image to enlarge.Source: Boston1908-1938, 1914 [map]. 1914. Scale not given. “Digital Sanborn Maps 1867-1970.” ProQuest. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000019.htm?CCSI=254n, sheet 7, 9, 37, 39 (12 March 2013).

Maps of Newbury Street in 1951. Click on each image to enlarge.Source: Boston 1929-1951, 1951 [map]. 1951. Scale not given. “Digital Sanborn Maps 1867-1970.” ProQuest. http://sanborn.umi.com/ma/3693/dateid-000035.htm?CCSI=254n, sheets 209, 210, 211, 212, 220, 222 (12 March 2013).

View Larger Map