|

A Carnot cycle is shown in Figure 3.4. It has

four processes. There are two adiabatic reversible legs and two

isothermal reversible legs. We can construct a Carnot cycle with

many different systems, but the concepts can be shown using a

familiar working fluid, the ideal gas. The system can be regarded as

a chamber enclosed by a piston and filled with this ideal gas.

Figure 3.4:

Carnot cycle -- thermodynamic diagram on left and schematic of the

different stages in the cycle for a system composed of an ideal gas

on the right

|

|

The four processes in the Carnot cycle are:

- The system is at temperature

at state

at state  . It is

brought in contact with a heat reservoir, which is just a liquid or

solid mass of large enough extent such that its temperature does not

change appreciably when some amount of heat is transferred to the

system. In other words, the heat reservoir is a constant temperature

source (or receiver) of heat. The system then undergoes an

isothermal expansion from

. It is

brought in contact with a heat reservoir, which is just a liquid or

solid mass of large enough extent such that its temperature does not

change appreciably when some amount of heat is transferred to the

system. In other words, the heat reservoir is a constant temperature

source (or receiver) of heat. The system then undergoes an

isothermal expansion from  to

to  , with heat absorbed

, with heat absorbed  .

.

- At

state

, the system is thermally insulated (removed from contact

with the heat reservoir) and then let expand to

, the system is thermally insulated (removed from contact

with the heat reservoir) and then let expand to  . During this

expansion the temperature decreases to

. During this

expansion the temperature decreases to  . The heat exchanged

during this part of the cycle,

. The heat exchanged

during this part of the cycle,  )

)

- At state

the system is

brought in contact with a heat reservoir at temperature

the system is

brought in contact with a heat reservoir at temperature  . It is

then compressed to state

. It is

then compressed to state  , rejecting heat

, rejecting heat  in the process.

in the process.

- Finally, the system is compressed adiabatically back to the

initial state

. The heat exchange

. The heat exchange  .

.

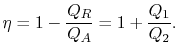

The thermal efficiency of the cycle is given by the definition

|

(3..4) |

In this equation, there is a sign convention implied. The quantities

,

,  as defined are the magnitudes of the heat absorbed and

rejected. The quantities

as defined are the magnitudes of the heat absorbed and

rejected. The quantities  ,

,  on the other hand are defined

with reference to heat received by the system. In this example, the

former is negative and the latter is positive. The heat absorbed and

rejected by the system takes place during isothermal processes and

we already know what their values are from Eq.

(3.1):

on the other hand are defined

with reference to heat received by the system. In this example, the

former is negative and the latter is positive. The heat absorbed and

rejected by the system takes place during isothermal processes and

we already know what their values are from Eq.

(3.1):

The

efficiency can now be written in terms of the volumes at the

different states as

![$\displaystyle \eta = 1+ \frac{T_1[\ln(V_d /V_c)]}{T_2[\ln(V_b /V_a)]}.$](img355.png) |

(3..5) |

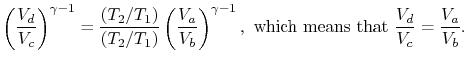

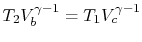

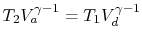

The path from states  to

to  and from

and from  to

to  are both

adiabatic and reversible. For a reversible adiabatic process we know

that

are both

adiabatic and reversible. For a reversible adiabatic process we know

that

. Using the ideal gas equation of

state, we have

. Using the ideal gas equation of

state, we have

. Along curve

. Along curve

-

- , therefore,

, therefore,

. Along

the curve

. Along

the curve  -

- ,

,

. Thus,

. Thus,

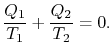

Comparing the expression for thermal efficiency

Eq. (3.4) with Eq. (3.5) shows

two consequences. First, the heats received and rejected are related

to the temperatures of the isothermal parts of the cycle by

|

(3..6) |

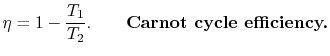

Second, the efficiency of a Carnot cycle is given compactly by

|

(3..7) |

The efficiency can be 100% only if the temperature at which the

heat is rejected is zero. The heat and work transfers to and from

the system are shown schematically in

Figure 3.5.

Figure 3.5:

Work and heat transfers in

a Carnot cycle between two heat reservoirs

|

|

Muddy Points

Since

, looking at the

, looking at the  -

- graph, does

that mean the farther apart the

graph, does

that mean the farther apart the  ,

,  isotherms are, the

greater efficiency? And that if they were very close, it would be

very inefficient? (MP 3.2)

isotherms are, the

greater efficiency? And that if they were very close, it would be

very inefficient? (MP 3.2)

In the Carnot cycle, why are we only dealing with volume changes and

not pressure changes on the adiabats and isotherms?

(MP 3.3)

Is there a physical application for the Carnot cycle? Can we design

a Carnot engine for a propulsion device?

(MP 3.4)

How do we know which cycles to use as models for real processes?

(MP 3.5)

UnifiedTP

|