Subsections

[VW, S & B: 9.8-9.9, 9.12]

The Brayton cycle (or Joule cycle) represents the operation of a gas

turbine engine. The cycle consists of four processes, as shown in

Figure 3.13 alongside a sketch of an engine:

- a - b Adiabatic, quasi-static (or reversible)

compression in the inlet and compressor;

- b - c Constant pressure fuel combustion (idealized as constant

pressure heat addition);

- c - d Adiabatic, quasi-static (or reversible) expansion in the

turbine and exhaust nozzle, with which we

- take some work out of the air and use it to drive the compressor, and

- take the

remaining work out and use it to accelerate fluid for jet

propulsion, or to turn a generator for electrical power generation;

- d - a Cool the air at constant pressure back to its initial

condition.

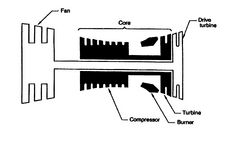

Figure 3.13:

Sketch of the jet engine

components and corresponding thermodynamic states

|

|

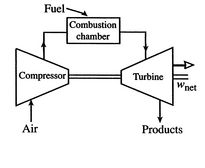

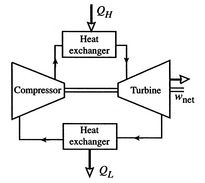

The components of a Brayton cycle device for jet propulsion are

shown in Figure 3.14. We will typically represent these

components schematically, as in

Figure 3.15. In practice, real Brayton

cycles take one of two forms. Figure 3.16(a)

shows an ``open'' cycle, where the working fluid enters and then

exits the device. This is the way a jet propulsion cycle works.

Figure 3.16(b) shows the alternative, a closed

cycle, which recirculates the working fluid. Closed cycles are used,

for example, in space power generation.

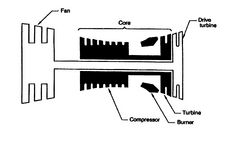

Figure 3.14:

Schematics of typical military

gas turbine engines. Top: turbojet with afterburning, bottom: GE

F404 low bypass ratio turbofan with afterburning (Hill and Peterson,

1992).

|

|

Figure 3.15:

Thermodynamic model of gas

turbine engine cycle for power generation

|

|

Figure 3.16:

Options for operating Brayton cycle gas turbine engines

[Open cycle operation]

[Closed cycle operation]

|

Muddy Points

Would it be practical to run a Brayton cycle in reverse and use it

as refrigerator? (MP 3.10)

3.7.1 Work and Efficiency

The objective now is to find the work done, the heat absorbed, and

the thermal efficiency of the cycle. Tracing the path shown around

the cycle from  -

- -

- -

- and back to

and back to  , the first law gives

(writing the equation in terms of a unit mass),

, the first law gives

(writing the equation in terms of a unit mass),

Here  is zero because

is zero because  is a function of state, and any

cycle returns the system to its starting state3.2. The net work done is therefore

is a function of state, and any

cycle returns the system to its starting state3.2. The net work done is therefore

where  ,

,  are defined as heat received by the system

(

are defined as heat received by the system

( is negative). We thus need to evaluate the heat transferred

in processes

is negative). We thus need to evaluate the heat transferred

in processes  -

- and

and  -

- .

.

For a constant pressure, quasi-static process the heat exchange per

unit mass is

We can see this by writing the first law in terms of enthalpy (see

Section 2.3.4) or by remembering the

definition of  .

.

The heat exchange can be expressed in terms of enthalpy differences

between the relevant states. Treating the working fluid as a perfect

gas with constant specific heats, for the heat addition from the

combustor,

The heat rejected is, similarly,

The net work per unit mass is given by

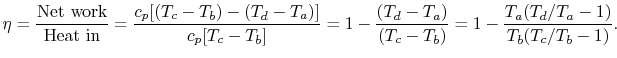

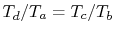

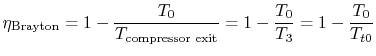

The thermal efficiency of the Brayton cycle can now be expressed in

terms of the temperatures:

|

(3..8) |

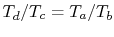

To proceed further, we need to examine the relationships between the

different temperatures. We know that points  and

and  are on a

constant pressure process as are points

are on a

constant pressure process as are points  and

and  , and

, and  ;

;

. The other two legs of the cycle are adiabatic and

reversible, so

. The other two legs of the cycle are adiabatic and

reversible, so

Therefore

, or, finally,

, or, finally,

.

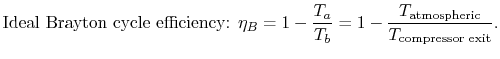

Using this relation in the expression for thermal efficiency,

Eq. (3.8) yields an expression for

the thermal efficiency of a Brayton cycle:

.

Using this relation in the expression for thermal efficiency,

Eq. (3.8) yields an expression for

the thermal efficiency of a Brayton cycle:

|

(3..9) |

The temperature ratio across the compressor,

. In terms

of compressor temperature ratio, and using the relation for an

adiabatic reversible process we can write the efficiency in terms of

the compressor (and cycle) pressure ratio, which is the parameter

commonly used:

. In terms

of compressor temperature ratio, and using the relation for an

adiabatic reversible process we can write the efficiency in terms of

the compressor (and cycle) pressure ratio, which is the parameter

commonly used:

|

(3..10) |

Figure 3.17:

Gas turbine engine

pressures and temperatures

|

|

Figure 3.17 shows pressures

and temperatures through a gas turbine engine (the PW4000, which

powers the 747 and the 767).

Figure 3.18:

Gas turbine

engine pressure ratio trends (Jane’s Aeroengines, 1998)

|

|

Figure 3.19:

Trend of Brayton cycle thermal efficiency with compressor pressure ratio

|

|

Equation (3.10) says that for a high cycle

efficiency, the pressure ratio of the cycle should be increased.

This trend is plotted in Figure 3.19.

Figure 3.18 shows the history of aircraft

engine pressure ratio versus entry into service, and it can be seen

that there has been a large increase in cycle pressure ratio. The

thermodynamic concepts apply to the behavior of real aerospace

devices!

Muddy Points

When flow is accelerated in a nozzle, doesn't that reduce the

internal energy of the flow and therefore the enthalpy?

(MP 3.11)

Why do we say the combustion in a gas turbine engine is constant

pressure? (MP 3.12)

Why is the Brayton cycle less efficient than the Carnot cycle?

(MP 3.13)

If the gas undergoes constant pressure cooling in the exhaust

outside the engine, is that still within the system boundary?

(MP 3.14)

Does it matter what labels we put on the corners of the cycle or

not? (MP 3.15)

Is the work done in the compressor always equal to the work done in

the turbine plus work out (for a Brayton cyle)?

(MP 3.16)

3.7.2 Gas Turbine Technology and Thermodynamics

The turbine entry temperature,  , is fixed by materials

technology and cost. (If the temperature is too high, the blades

fail.) Figures 3.20 and 3.21

show the progression of the turbine entry temperatures in

aeroengines. Figure 3.20 is from Rolls Royce and

Figure 3.21 is from Pratt & Whitney. Note the

relation between the gas temperature coming into the turbine blades

and the blade melting temperature.

, is fixed by materials

technology and cost. (If the temperature is too high, the blades

fail.) Figures 3.20 and 3.21

show the progression of the turbine entry temperatures in

aeroengines. Figure 3.20 is from Rolls Royce and

Figure 3.21 is from Pratt & Whitney. Note the

relation between the gas temperature coming into the turbine blades

and the blade melting temperature.

Figure 3.20:

Rolls-Royce high temperature

technology

|

|

Figure 3.21:

Turbine blade cooling

technology [Pratt & Whitney]

|

|

For a given level of turbine technology (in other words given

maximum temperature) a design question is what should the compressor

be? What criterion should be used to decide this? Maximum

thermal efficiency? Maximum work? We examine this issue below.

be? What criterion should be used to decide this? Maximum

thermal efficiency? Maximum work? We examine this issue below.

Figure 3.22:

Efficiency and work of two

Brayton cycle engines

|

|

The problem is posed in Figure 3.22, which

shows two Brayton cycles. For maximum efficiency we would like  as high as possible. This means that the compressor exit temperature

approaches the turbine entry temperature. The net work will be less

than the heat received; as

as high as possible. This means that the compressor exit temperature

approaches the turbine entry temperature. The net work will be less

than the heat received; as

the heat received

approaches zero and so does the net work.

the heat received

approaches zero and so does the net work.

The net work in the cycle can also be expressed as  ,

evaluated in traversing the cycle. This is the area enclosed by the

curves, which is seen to approach zero as

,

evaluated in traversing the cycle. This is the area enclosed by the

curves, which is seen to approach zero as

.

.

The conclusion from either of these arguments is that a cycle

designed for maximum thermal efficiency is not very useful in that

the work (power) we get out of it is zero.

A more useful criterion is that of maximum work per unit mass

(maximum power per unit mass flow). This leads to compact propulsion

devices. The work per unit mass is given by:

where  is the maximum turbine inlet temperature (a design

constraint) and

is the maximum turbine inlet temperature (a design

constraint) and  is atmospheric temperature. The design

variable is the compressor exit temperature,

is atmospheric temperature. The design

variable is the compressor exit temperature,  , and to find the

maximum as this is varied, we differentiate the expression for work

with respect to

, and to find the

maximum as this is varied, we differentiate the expression for work

with respect to  :

:

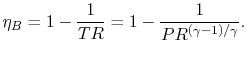

The first and the fourth terms on the right hand side of the above

equation are both zero (the turbine entry temperature is fixed, as

is the atmospheric temperature). The maximum work occurs where the

derivative of work with respect to  is zero:

is zero:

|

(3..11) |

To use Eq. (3.11), we need to relate  and

and  .

We know that

.

We know that

Hence,

Plugging this expression for the derivative into

Eq. (3.11) gives the compressor exit temperature for

maximum work as

. In terms of temperature

ratio,

. In terms of temperature

ratio,

The condition for maximum work in a Brayton cycle is different than

that for maximum efficiency. The role of the temperature ratio can

be seen if we examine the work per unit mass which is delivered at

this condition:

Ratioing all temperatures to the engine inlet temperature,

To find the power the engine can produce, we need to multiply the

work per unit mass by the mass flow rate:

![$\displaystyle \textrm{Power} = \dot{m} c_p T_a \left[\frac{T_c}{T_a} -2\sqrt{\frac{T_c}{T_a}}+1\right];\textrm{ Maximum power for an ideal Brayton cycle}.$](img437.png) |

(3..12) |

The trend of work output vs. compressor pressure ratio, for

different temperature ratios

, is shown in

Figure 3.23.

, is shown in

Figure 3.23.

Figure 3.23:

Trend of cycle work with compressor pressure ratio,

for different temperature ratios

|

|

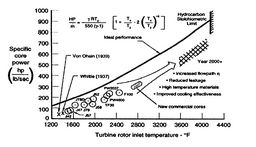

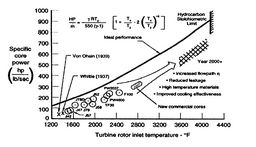

Figure 3.24:

Aeroengine core power [Koff/Meese,

1995]

[Gas turbine engine core]

[Core power vs. turbine entry

temperature]

|

Figure 3.24 shows the expression for power of an ideal

cycle compared with data from actual jet engines.

Figure 3.24(a) shows the gas turbine engine layout including

the core (compressor, burner, and turbine).

Figure 3.24(b) shows the core power for a number of

different engines as a function of the turbine rotor entry

temperature. The equation in the figure for horsepower (HP) is the

same as that which we just derived, except for the conversion

factors. The analysis not only shows the qualitative trend very well

but captures much of the quantitative behavior too.

A final comment (for this section) on Brayton cycles concerns the

value of the thermal efficiency. The Brayton cycle thermal

efficiency contains the ratio of the compressor exit temperature to

atmospheric temperature, so that the ratio is not based on the

highest temperature in the cycle, as the Carnot efficiency is. For a

given maximum cycle temperature, the Brayton cycle is therefore less

efficient than a Carnot cycle.

Muddy Points

What are the units of  in

in

?

(MP 3.17)

?

(MP 3.17)

Question about the assumptions made in the Brayton cycle for maximum

efficiency and maximum work

(MP 3.18)

You said that for a gas turbine engine modeled as a Brayton cycle

the work done is  , where

, where  is the heat added and

is the heat added and

is the heat rejected. Does this suggest that the work that you

get out of the engine doesn't depend on how good your compressor and

turbine are?

is the heat rejected. Does this suggest that the work that you

get out of the engine doesn't depend on how good your compressor and

turbine are? since the compression and expansion were modeled

as adiabatic. (MP 3.19)

since the compression and expansion were modeled

as adiabatic. (MP 3.19)

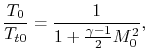

3.7.3 Brayton Cycle for Jet Propulsion: the Ideal Ramjet

A schematic of a ramjet is given in

Figure 3.25.

Figure 3.25:

Ideal ramjet

[J. L. Kerrebrock, Aircraft Engines and Gas Turbines]

|

|

In the ramjet there are ``no moving parts.'' The processes that

occur in this propulsion device are:

-

: Isentropic diffusion

(slowing down) and compression, with a decrease in Mach number,

: Isentropic diffusion

(slowing down) and compression, with a decrease in Mach number,

.

.

-

: Constant pressure combustion.

: Constant pressure combustion.

-

: Isentropic expansion through the nozzle.

: Isentropic expansion through the nozzle.

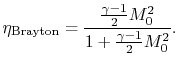

The ramjet thermodynamic cycle efficiency can be written in terms of

flight Mach number,  , as follows:

, as follows:

and

so

See also Section 11.6.3 for other figures of merit.

Muddy Points

Why don't we like the numbers 1 and 2 for the stations? Why do we go

0-3? (MP 3.20)

For the Brayton cycle efficiency, why does

?

(MP 3.21)

?

(MP 3.21)

MIT operates a Brayton cycle power generator on campus. For more

information, see the website at

https://cogen.mit.edu/ctg.cfm

.

Douglas Quattrochi

2006-08-06

|

[Core power vs. turbine entry

temperature]

[Core power vs. turbine entry

temperature]

![]() in

in

![]() ?

(MP 3.17)

?

(MP 3.17)

![]() , where

, where ![]() is the heat added and

is the heat added and

![]() is the heat rejected. Does this suggest that the work that you

get out of the engine doesn't depend on how good your compressor and

turbine are?

is the heat rejected. Does this suggest that the work that you

get out of the engine doesn't depend on how good your compressor and

turbine are?![]() since the compression and expansion were modeled

as adiabatic. (MP 3.19)

since the compression and expansion were modeled

as adiabatic. (MP 3.19)

![]() , as follows:

, as follows:

![]() ?

(MP 3.21)

?

(MP 3.21)