international conference  april 27-29, 2007 april 27-29, 2007  mit mit

Folk Cultures and Digital Cultures

Friday, April 27, 2007

12:30-2:00

E25-111

Digital visionaries such as Yochai Benkler have described the emergence of a new networked culture in which participants with differing intentions and professional credentials co-exist and cooperate in a complex media ecology. Are we witnessing the appearance of a new or revitalized folk culture? Are there older traditions and practices from print culture or oral societies that resemble these emerging digital practices? What sort of amateur or grassroots creativity have been studied or documented by literary scholars, anthropologists, and students of folklore? How were creativity and collaboration understood in earlier cultures? Are there lessons or cautions for digital culture in the near or distant past?

Speakers

Lewis Hyde is the Thomas Professor of Creative Writing at Kenyon College and a fellow of the Berkman Center on Internet and Society at the Harvard Law School. He is a poet and essayist whose current book project is a defense of cultural commons. His book Trickster Makes This World (1999) is a portrait of the kind of disruptive imagination needed to keep any culture flexible and lively. email

Thomas Pettitt is an associate professor at the Institute of Literature, Media and Cultural Studies, University of Southern Denmark, where he lectures on late-medieval and early-modern literature and theatre, and on folk traditions. email

S. Craig Watkins writes about race, youth, media, and technology. His most recent book is Hip Hop Matters: Politics, Pop Culture and the Struggle for the Soul of a Movement. He is currently working on a book examining the social consequences and implications of young people's changing media behaviors. He teaches at the University of Texas at Austin. email

Moderator:

David Thorburn is professor of literature and director of the Communications Forum at MIT. He is the author of Conrad’s Romanticism, and, most recently, co-editor of Rethinking Media Change: The Aesthetics of Transition. email

Summary

By Huma Yusuf, CMS ‘08

[This is an edited summary, not a verbatim transcript.]

Panel moderator David Thorburn began “Folk Cultures and Digital Cultures” by explaining the rationale for MIT’s Comparative Media Studies (CMS) program and the Media in Transition conferences. He said that one way to think about new media is to confront the issue of whether we belong to a “futurist school,” comprised of people who are focused on contemporary and future events; or whether we want to emphasize the “backwards-looking” school comprised of traditional literary scholars, anthropologists and folklorists who are aware of the extent to which there are complex and potentially instructive analogies between older cultural practices and behaviors that can be seen in emerging cultural practices.

Thorburn said that sustaining, clarifying, and concretizing a dialogue between the past and future is a critical focus of CMS and the conferences.

One consequence of this dialogue between the past and the present is the recognition that there has been a breakdown in the confidence that the categories of high and popular culture are meaningful categories. Thorburn elaborated that revered, central figures in the museum of high culture such as Homer and Shakespeare in their own time belonged to the popular culture. The implications of this, he said, have still not been fully understood or absorbed by traditional scholarship or, for that matter, the digitally inflected awareness of contemporary scholars. He said that it is a complex and enabling idea that Shakespeare in his own day was the equivalent of television today and movies in the studio era.

Thorburn went on to say that old-taste hierarchies have become problematic and we no longer unconsciously recognize elite culture without emphasizing the inadequacy of this conception. In that context, the central idea that the text is some finished thing has been undermined. Much current work in traditional literary fields as well as on emerging digital forms suggests that textual systems are always in progress, ongoing, and never reach a definitive state of completion.

Texts undergo transformations and transmogrify as the surrounding technologies and environments change. The idea that there’s a final version of a text that distills its essence and makes textual variations that come after seem minor or ancillary is becoming redundant. The founding texts of western civilization, Thorburn pointed out, engaged in textual behaviors that resemble the unfinished discourse centered on forms of popular culture that elaborate themselves over time, across media systems and generations.

Thorburn then introduced the three plenary speakers.

Thomas Pettitt presented a talk titled “Before the Guttenberg Parenthesis: Elizabethan-American Compatibilities.” He said that he was at the conference to explain what he found Elizabethan about contemporary American media and what he found American, particularly African-American, about Shakespeare.

Pettitt pointed to several of the phrases that dominated the titles of Media in Transition conference papers – "sampling," "remixing," "recontextualizing," "appropriating" – and joked that these characterized the way in which his students approached paper writing. He said his students constructed – or as folklorists would say, "quilted" – an essay out of diverse materials accessed on the Internet and manipulated using digital technology. But he argued that while these student practices were awful, no generation of students has been better qualified to appreciate Shakespeare and the significant practices of sampling and remixing that gave rise to plays and determined their treatment in Elizabethan theater.

Pettitt said that when his students compile papers, they’re reprimanded for plagiarism, a fate they share with some Elizabethan dramatists. He then pointed to the notorious attack by Robert Green in 1592 on a “provocative” new rival, a “mere player who considers himself to be the only shake-scene in the country,” and who thinks that he can “bombast out blank verse” in the manner of university-trained playwrights.

Quoting from Green’s critique of Shakespeare, Pettitt referred to the Bard as “merely an upstart crow beautified with our feathers.” Pettitt was making the point that just as his students have something in common with Shakespeare, he has something in common with Green, which is that they are both speaking from within what he calls the “Gutenberg Parenthesis.”

Pettitt defines the Gutenberg Parenthesis as a space within which all cultural products, including stage plays and student essays, are assumed to be original and autonomous, the individual and independent achievements and property of those who create them. Pettitt points out that Green was castigating a Shakespeare who was working within a popular form of Elizabethan entertainment that deemed sampling as legitimate. As a way of comparison, Pettitt said that he reprimands his students who plagiarize for participating in a digital Internet culture which is already on its way out of the Gutenberg Parenthesis, in which sampling and remixing are becoming legitimate. He then joked that in true digital fashion, he too plagiarized the title of his presentation from a research project on the same theme that his colleagues at the University of Denmark are currently working on. They in turn are indebted to Marshall McLuhan’s The Gutenberg Galaxy.

Pettitt explained that his attraction to the parenthesis stems from its implication of a development over time. A parenthesis necessarily involves a before, during, and after, with the understanding that what comes before and what comes after have more in common with each other than what comes in between. After all, a parenthesis interrupts a sentence and only when it is over does the sentence resume where it left off. Pettitt compared this grammatical structure with the present-day notion of paradoxically advancing into the past.

In borrowing the Gutenberg Parenthesis from his colleagues, Pettitt said that he did the same that Shakespeare did to Kit’s Hamlet and the Travelling Players did to Shakespeare’s Hamlet, that is, make it his own. For him the difference between the world within the parenthesis and the world without is the respective significance given to the composition of the work on the one hand, and the performance of the work on the other hand. He also accords significance to the amount of borrowing required from other materials with regards to both the composition and the performance of the work. His premise therefore is that an original composition with a single creator and featuring no borrowed materials lies at the center of the parenthesis. At the other extreme, outside the parenthesis, lies the performance, which owes something to earlier performances and much to other performances, with materials coming in from the sides. Pettitt did state though that he still needs to think about exactly where the parenthesis should be inserted in this spectrum.

Pettitt used the parenthesis as a way to show the compatibility between the Elizabethan era and the modern American media landscape. He said that if modern media is described as moving into the post-parenthetical realm where the distinctions between author and consumer and problematic and plagiarism is the norm, then the Elizabethan theater scene that regarded Shakespeare as both author and consumer should be regarded as the pre-parenthetical mirror image of where we are now. Pettitt pointed to Douglas Brewster’s comment that since Elizabethan plays quote without acknowledging their sources, scholars within the parenthesis will have to reevaluate how well their notions of property, language, and textuality apply to early modern drama.

|

Lewis Hyde first clarified that in the context of the plenary, he understood the phrase "folk culture" to mean community protocols that arise without the structure and protection of the law. He began his presentation with the example of Chester Moore Hall who in 1733 invented an achromatic telescope doublet, a telescope lens made of two kinds of glass that gets rid of an effect known as color flare. Hall had the first doublets made by opticians and other instrument makers in London. His innovation soon became common knowledge within the optical industry in London, but since it was a trade secret, knowledge of how to build a doublet did not extend beyond the city. Thus, about two decades later, John Dolland reinvented the achromatic telescope doublet, patented his invention, and began to charge royalties for its use. The case went to court when instrument makers in London refused to pay royalties for a device they had been using well before Dolland patented it.

Ultimately, Dolland won the case because the court decided that patents should afford commercial advantages not because the holder of the patent invented something, but because he disclosed his knowledge to the public and ensured that when his patent expired, the public could have free access to the knowledge in perpetuity.

Hyde then explained that trades and guilds had a knowledge economy, by which he meant that knowledge was kept secret, sometimes for centuries, to maintain a trade advantage. Subsequently, however, there was a shift as a new ethos that Hyde called the “republic of letters” began to emerge. Patents, he explained, became a formal way to transform trade secrets into public knowledge. The less formal, or folk, version of this practice is piracy. To elaborate on this claim in an American context, Hyde turned to the example of Benjamin Franklin, and recounted how Franklin began his adult life with an act of theft.

Hyde explained that Franklin stole himself out of an apprenticeship with his brother by breaking the certificates of indentures that legally bound him to his brother and fleeing to Philadelphia. Hyde adds that Franklin describes in his autobiography how he was scared that he’d be arrested for committing a crime. After all, maintaining certificates of indentures was the way knowledge was controlled in an apprentice system. The free movement of labor was akin to the free movement of knowledge. In that way, Franklin was America’s first intellectual property pirate.

Hyde went on to give a second example from Franklin’s mature years that demonstrated knowledge sharing. In 1781, when Franklin was in Paris representing his new nation and helping people come up with schemes to facilitate emigration to America, a young man named Henry Royal approached him. Although he was not interested in Royal’s proposed machinery, Franklin encouraged him to look into a special law that would give Royal possession of any machines he invented for up to seven years. This was the unique moment in which Franklin assented to a patent.

The process is known as a patent of importation, whereby someone who brings a new technique into a country is granted a limited monopoly over it. Hyde explained that Franklin was a pragmatist who was not opposed to intellectual property rights, but acknowledged that Royal’s scheme amounted to trade piracy because British law at the time forbade the emigration of skilled labor and the machinery they might use. In encouraging Royal’s emigration, then, not only was Franklin supporting intellectual property rights, but he was also supporting the free movement of labor and ideas. Indeed, in a letter to Royal, Franklin described English laws as tyrannical and compared England to a prison that detains young men for being industrious.

Hyde concluded his presentation by elaborating on his earlier use of the term, republic of letters. He explained that in the Roman category of law, harbors, bridges, and other infrastructure were known as “public things.” The eighteenth century worked off this earlier notion and reconfigured creative work as republican property as well. This shift was meant to meet two ends: to progress the cause of knowledge and to enable self-governance.

According to Hyde, the understanding was that in order to create a political republic, people needed access to public knowledge as well. Hyde then summarized his argument as follows: trade piracy, as practiced in the eighteenth century and exemplified in Franklin’s life, was foundational to both American science and democracy.

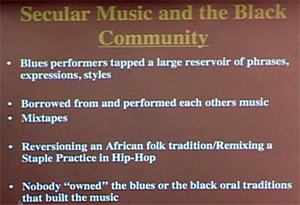

Craig Watkins’ presentation was titled “Remixed: Black Orality, Technology, and Cultural Practice” and was concerned with the way in which black American cultural practices of the past enable an understanding of current cultural practices, primarily hip hop music. Watkins said that creative chaos – remixing, sampling, reconfiguring of the past – is a defining element of hip hop. He argued that not only was hip hop built on those practices, but that black folk tradition and black oral culture also inform and engage current practices.

Watkins began with a quote from folklorist Neuman White, made at the turn of the last century, describing black folk and secular music, yet pertaining to current rhythms in hip hop: “the notes and songs in my whole collection show nothing so clearly as the tendency of Negro folk song to pick up material from any source and by changing it or using it in all sorts of combinations to make it definitely its own.”

Watkins went on to say that the quote typifies some of the pioneering practices of hip hop DJs, including Afrika Bambaataa, Grandmaster Flash and DJ Kool Herc, the grandfather of hip hop culture, who was born in Jamaica and brought African folklore traditions to New York City when he immigrated in the early 1970s.

Watkins then reminded the audience that rap music is rooted in twentieth century black oral tradition and cultural practices but goes back to the hidden transcripts and oral cultures of slaves. He recalled that language has always been used by African-Americans in subtle ways to facilitate protest politics, initially through protest songs, and subsequently in a more vocal manner.

This black folk tradition created a communal oral space in which to engage in dialogue to make sense of and even survive horrible conditions. Watkins then expanded his definition of black oral culture beyond hip hop to include slave narratives and the sermons of black preachers as well as the work of black comedians such as Richard Pryor.

Watkins then introduced Walter Ong’s notion of post-literate orality, which is concerned with ways in which oral tradition is revised and presented in technologically upgraded environments. He then referred to Tricia Rose’s book Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America in which she argues that rap simultaneously makes technology oral – because rap artists use it as a means of communication – and technologizes orality.

Watkins then pointed out the importance of sampling in hip hop culture. The practice has been a mainstay of hip hop creativity for almost 40 years and the digital sampler has become a quintessential component of the culture as producers have evolved their use of sampling techniques.

Watkins acknowleged that sampling is viewed very differently by the music industry at large. He explained that sampling is seen as a primitive form of music, tainted with the ideas of theft and copyright infringement. He pointed out that sampling is seen as an economic transaction at best – in the sense of purchasing copyright to some beats – and legal transgression at worst. The idea was to emphasize the discrepancy between the music industry’s understanding of sampling and the hip hop community’s view of sampling as a creative, dynamic process, a complex practice of sound theory aimed at organizing sound.

|

Watkins emphasized that black music has long been thought of as a participatory activity both by the African-American community as well as by historians. While citing call-and-response as the most famous example of participation in black oral tradition, Watkins again referred to the interactive nature of black orality, including slave songs, work songs, the inspirational speeches of leaders, black preachers, and work of black rappers.

Panel Discussion

Pettitt framed Watkins’ presentation in terms of his discussion of the Gutenberg Parenthesis. He explained that if he were to include African-American vernacular tradition within his paradigm, it would appear within the parenthesis at a much later date than other cultural practices owing to the tendency to sample and remix. He then questioned whether there had ever been a time – perhaps in the mid-twentieth century – when African-American culture could be included within the parenthesis and if, for example, there might have been blues artists who claimed ownership of certain songs and acknowledged songs to be someone else’s during live performances.

Watkins said the answer to Pettitt’s question was both yes and no. He explained that most historians focus their analysis of black music on the gospel tradition and slave songs that were largely communal practices. But he pointed out that the image of the blues performer armed with a guitar and usually performing alone suggests that for the first time, African-American music was moving towards individualization.

According to Watkins, however, a notion of fixedness or authorship never existed among blues musicians. They knew that songs were meant to be recreated, elaborated, and performed in a variety of ways that opened the music up to a communal experience and exemplified the traits of participatory culture, which was decidedly inconsistent with emerging industrial regimes.

Thorburn suggested that Pettitt and Watkins’ comments evoked larger questions about the stability and limits of the text.

Hyde then made a comment about so-called trickster figures, who appear when things are ambiguous and cross boundaries. Hyde recounted a story from Hindu tradition about Krishna who stole butter from his family larder, and when reprimanded by his mother, asked why the theft was problematic if everything in the house belonged to the family.

Hyde explained that what is useful about this story is that it teaches us to call into question the categories by which we organize our world. Should we define what Franklin did as piracy or innovation? He then asked Pettitt whether the Gutenberg Parenthesis applied in the same way to science as it did to literary theory. His point was that print culture for Franklin was part of an open discourse and did not privilege fixing ideas as much as participating in an ongoing discourse. Hyde suggested that ownership perhaps counted differently in the scientific and literary worlds.

Presentations

Before the Gutenberg Parenthesis: Elizabethan-American Compatibilities, Thomas Pettitt

Audiocast

An audio recording of Folk Cultures and Digital Cultures is now available.

In order to listen to the archived audiocast, you can install RealOne Player. A free download is available at http://www.real.com/realone/index.html .

Podcast

A podcast of Folk Cultures and Digital Cultures is now available from Comparative Media Studies.

Video

A webcast of Folk Cultures and Digital Cultures is available.

top

|