St Vincent and the Grenadines

La Soufriere

Eric and Matthew Gilbertson

Date: March 24, 2012

On the summit of La Soufriere, roof of St Vincent and the Grenadines

A well-marked trailhead

Left: The crater rim - this is the end of the trail and where most (aka all) people stop. Right: Matthew pointing to the true summit

Left: Our ascent route - the Gilbertson Gully. Right: Matthew ascending some Grade 10 bushwacking.

Left: Looking up at the crux of our route - vertical bushwacking. Right: Eric after successfully climbing the 15ft vertical crux

Left: On the summit ridge pointing to the summit. Right: Matthew descending.

Left: Some tricky downclimbing in the dry riverbed. Right: Finally back to the trail on the crater rim, but not out of the rain.

Eric being interviewed by SVGTV news after a successful summit bid on La Soufriere.

More pictures here: http://mitoc.mit.edu/gallery/main.php?g2_itemId=311766

St Vincent & the Grenadines - La Soufrière (1236m)

Matthew and Eric Gilbertson

3/23/12-3/24/12

LINKS:

Our adventures page

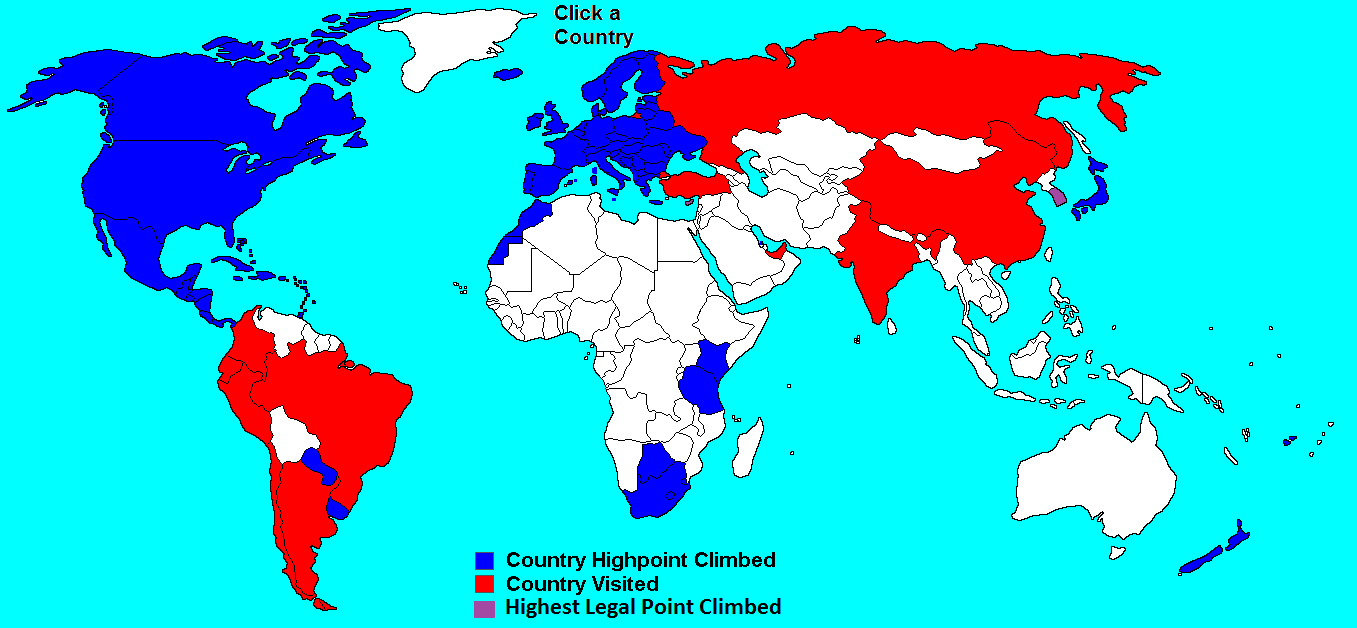

Our country high points page

Author: Matthew

“So tell us about your hike today; which mountain did you guys climb?” The reporter tilted the microphone towards me and the video camera zoomed in.

“We climbed to the top of La Soufrière,” I replied, not sure whether to look at the reporter or the camera. Obviously the news team from Saint Vincent and the Grenadines TV (SVGTV) knew full well which mountain we had just climbed – we were standing here at the trailhead for La Soufrière, the highest mountain in this tiny Caribbean island nation. They just wanted to orient viewers at home.

“And how was your hike?”

“It wasn’t easy I answered.” My gaze descended slowly past my bloody, lacerated arms, past the muddy, gruesome gashes on my legs and settled onto my feet.

“And you hiked in those?” she asked, referring to the foam crocs (slippers) I was wearing.

“I had to because LIAT [the airline] lost my backpack, which had my shoes, pants, food, and rain jacket.”

The camera slowly ascended and focused in on my arms. They wanted the viewers on their couches at home to get a good look at the damage inflicted by their country’s tallest peak. Oh if they could only know how hard it had been…

****

GETTING TO ST VINCENT

La Soufrière would be country high point number three of the trip for me and Eric. We had just come off successful ascents of Trinidad and Tobago’s Cerro del Aripo and Grenada’s Mt St Catherine the previous two days and were hoping to be three-for-three after St Vincent and the Grenadines. It was Spring Break for us and we wanted to knock off a few country high points, with Barbados, Antigua, and Dominica next on the list.

Just like the other two mountains, hours of internet searching in Cambridge had yielded precious little information about La Soufrière. We knew simply that it started at the “Rabacca” trailhead in the northern part of the island. We also had a GPS track from another hiker but were uncertain of its accuracy. We realized then that we might have to gather some info from locals when we landed.

The few trip reports we found all said that either “you are required to hire a guide” or “you darn well better hire a guide.” But based on Google Maps terrain research the route looked pretty straightforward, so we figured we’d be able to figure things out ourselves without a guide. The only question would be which peak was highest – Google Earth’s topo data showed that a few nearby peaks were all within ten feet elevation of each other. To make things even harder, in every single satellite photo (Google Maps, Bing Maps, and Garmin Satellite Imagery) the true summit of La Soufrière was socked in with clouds and thus invisible. We could find no hiker photos of the true summit either. But we just assumed that enough people probably climb the mountain that the true summit and trail would be pretty obvious. (Boy were we wrong about that.)

The original plan had been to sneak in La Soufrière during an eleven-hour window between Grenada and Barbados. We’d fly into St Vincent 11am, clear customs, pick up a rental car and hit the road, reaching the trailhead at 1pm. We’d finish the (apparently) four hour hike by 5pm, be back at the airport by 7pm and have 3 hours until our 10pm flight to Barbados. Somehow, though, we managed to finish Mt St Catherine in Grenada in record time and miraculously caught an earlier flight to St Vincent, which landed at 5pm, which meant we’d have an extra three-fourths of a day for La Soufrière. That move would turn out to be crucial to our success.

THE CHECKBOX

The first indication that La Soufrière would not be easily defeated came shortly after we landed. “So where are you guys staying tonight?” the immigration officer asked. “We’re on a big hike tomorrow so we’ll just sleep in our rental car at the trailhead.” On the customs form, in the little box that said “YOUR INTENDED ADDRESS IN ST VINCENT:” we had just written “Airport,” figuring it’d be an acceptable response, as it had been in Trinidad and Grenada. We explained the situation.

The immigration officer thought about it for a while, then summoned her superior. “That’s fine if you want to camp, but I can’t let you into the country without a hotel address on this form,” the superior said. “I’d suggest talking to our travel agent over here, she will let you know which hotels were available.”

With disdain we walked over to the travel agent. By this point we had the attention of all three of the immigration officers in the entire country. Everyone in the room knew that no matter which hotel room we reserved we wouldn’t be staying in a hotel tonight. But they would be satisfied if they could simply check off the box that said they had an address for us. I talked to one hotel and made quick reservation, then scribbled their address in the correct box. Trying to keep a straight face, the immigration officer looked once more at our immigration forms, then gave a nod of approval. Welcome to Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.

“Please proceed to customs next,” she said. Which brings us to Snafu #2 of the trip.

OUR FRIENDS AT LIAT

We waited patiently at the conveyor belt as the luggage went around and people claimed their suitcases. Lest the reader overestimates the size of the SVD airport, I’ll should set the record straight: the baggage claim conveyor belt loop cycle time is about seven seconds. Our flight was one of probably only four that day. There’s one immigration officer booth, and I believe that most of the airport staff was napping before we arrived. Before long all of the luggage was claimed, but my backpack was nowhere to be found.

“Dang it,” I said to Eric. Earlier we had read online about LIAT’s dismal record with lost luggage and had sworn to check no bags during our trip. Our schedule was so tight that we couldn’t afford to waste two hours waiting for a bag. Hours earlier in Grenada, however, we had to move very quickly as soon as we arrived at the ticket counter and realized that we had only minutes before the earlier flight departed. The LIAT rep weighed my bag and said it was 20lbs – too heavy for carry-on luggage on these tiny Caribbean planes. Ten of those pounds was probably the mud and swamp water from Mt St Catherine that had saturated my shoes and clothes. I had traded out the muddy outfit in favor of my clean clothes and crocs for the flight.

“We’re going to have to check this bag,” he said. We were in such a hurry to catch the earlier flight that I hastily removed my electronics (GPS, cell phone, and camera) from the backpack and reluctantly handed the backpack over without arguing. The pack contained my ultra-thin sleeping bag, rain jacket, air mattress, bug net shelter, international driver’s permit, and sunscreen. I remember thinking, “Wow, I’ll be in trouble if they lose that bag. I can’t hike in the outfit I’m wearing. But there’s no way they’d lose my backpack.” Little did I know that the bag also contained my glasses, contact solution, spare contacts, Android phone, food, and the precious route descriptions which we had spent countless hours compiling.

Well lo and behold we were here in Kingstown, St. Vincent and the backpack was nowhere to be found. “Crap,” I said. We headed straight over to the LIAT ticket counter to sort things out. They said the next flight wouldn’t arrive for another three hours. We weighed our options. “Is there any place in town where I could buy some shoes, pants, and contact solution? We’re hiking up La Soufrière tomorrow and would like to leave tonight.” I didn’t want to be bushwhacking through no Caribbean jungle wearing little more than beach attire.

“No, I’m sorry” the LIAT rep replied, “everything closes early here on Friday night. The stores won’t open again until Monday.”

“Crap.” Eric and I began to deliberate. We could either 1) wait three hours until the next flight –but what’s the likelihood my backpack will be on that one? or 2) stay in a hotel tonight and see if we can find some store in the morning to buy shoes or 3) hit the road tonight and suck it up tomorrow without long pants, shoes, or a rest for my weary eyes.

We didn’t want to blow our lead. “When the bag arrives,” I said, “please hold it at the front desk and we’ll pick it up tomorrow. We’d like to start hiking tonight.”

“As you wish,” she replied. “I hope you enjoy your time here in St. Vincent and this incident doesn’t put a damper on your hike to La Soufrière.”

With frustration we stormed out of the airport. Well at least once we get the rental car things will be in our hands, I remember thinking. I can tolerate one night without taking out my contacts, along with some light bush whacking with less-than-ideal footwear, if it means that we’ll be able to finish this mountain. I mean, the backpack will surely arrive before we leave tomorrow night, right? We walked over to the Avis parking lot to pick up our rental car, which brings us to Snafu #3.

OUR FRIEND MR. CURTIS

Our actual rental car reservation was for the following day at 11am, but since we’d read that Avis was open until 9pm and there seemed to be quite a few cars in the parking lot, we figured we’d walk over there and easily pick one up early. We knocked on the door to the office. No answer. Wait a few minutes, knock again, still no answer. Hmm. “This isn’t looking good,” I said, “let’s call one of those numbers written on the Avis sign.” But in order to use a payphone I’d first need some St Vincent cash.

I walked over to some taxi drivers at the airport. “Do you know where I could exchange some currency?” I asked. “Sorry,” one man answered, “the banks close early on Fridays, you’ll have to wait until Monday, what’s the problem mon?” We were starting to notice a theme here. “Here’s the situation,” I said, “we’d like to rent a car from Avis, and they’re supposed to be open now, but there’s nobody in the office.”

One taxi driver, who later introduced himself as Peech, stepped forward. “I know the owner of Avis, let’s give him a call.” He dialed the numbers on his phone, but still no answer. “Well I know where he lives; I can give you a ride over there.” We hopped into his taxi and sped off into the hills above Kingstown. “This is Cane Gardens,” Peech said, “it’s where all the rich people live.” We continued climbing up the hill until we arrived at a car dealership. “That’s Curtis right there, he owns Avis, catch him quick.” Curtis had just opened his car door and was getting ready to leave when we approached him.

With a smile he said “you’re just in time, come in here and I’ll get you a car.” Turns out Curtis owns a car dealership too. We stepped into his office and I immediately had a little uneasy feeling about Mr. Curtis. It was hard to put my finger on it, but he and his employees seemed a little bit slick. Maybe it just came from being a used car salesman, I thought. I tried to push it out of my mind. We had been lucky to catch him before he left for the evening.

The paperwork went smoothly, especially because Eric already had already gotten an International Drivers Permit from AAA in Boston, which meant that we wouldn’t need to pay a visit to the already-closed Kingstown Police Station for a local permit. “We’ve got a four-door Suzuki jeep for you,” he said as he showed us to the door. Perfect! we thought. We wouldn’t need to worry about rough roads with that vehicle. “And in St Vincent we drive on the …” Curtis said. “Left,” Eric responded. The past few days Eric had had a decent bit of experience with left-side-driving so he figured that he could handle St Vincent too. With a grin Curtis waved us goodbye. But there was something subtle in his grin that made me feel uneasy.

Somehow Curtis had managed to provide us with fuel tank that read sub-empty so we knew we’d have to gas up ASAP before the two-hour drive to the trailhead. We stopped at Shell where I picked up some ice cream then made another stop to get some spoons at a local restaurant. I triumphantly returned to the car with the plastic spoons. With a half-gallon of ice cream we were equipped for the journey ahead. Eric inserted the keys into the ignition, which brought us to Snafu #4 for the trip.

THANK YOU MR. PEECH

Eric rotated the keys but the car would not respond. “Uh that’s not good,” he said. Try again. We could hear the spinning of what we figured was the starter motor, but engine wouldn’t start. Soon the starter stopped spinning and the car was silent. “Uh-oh, that probably means the battery is dead,” I said. We waited another few minutes and tried again. Nothing. “Let’s go talk to Peech, see what we can do,” I said.

Once again we walked down the little hill to the airport and consulted our friend Mr. Peech. He tried dialing all the phone numbers for Curtis, the car’s owner, but couldn’t get through. We also tried the number on top of the rental agreement, which should theoretically get you through to a person 24 hours a day in case of emergency. Nothing. “Let’s go to Cane Gardens and see if we can catch him,” Peech said. Once again we hopped into his taxi and sped up the hill. But when we arrived at Curtis’s car dealership it was deserted. “OK, let’s drive to Curtis’s house.” We drove a little farther down the road to his house but still it was also empty. “OK, let’s drive to his pharmacy – he owns a pharmacy downtown.” But big surprise the Curtis Lewis Pharmacy was also closed. We tried the phone numbers once again. Nothing. Our options were running low.

“Where’s this car parked? Let’s take a look at it,” Peech said. We drove over and he parked his taxi van alongside our Suzuki. He popped the hood and looked at the battery. He listened while we tried to start it. “Yes, your battery is dead,” he said. He grabbed some jumper cables from his car. We stepped back while he went to work. By this time a small crowd had gathered around us, offering suggestions. We were the entertainment in Kingstown for the night.

He started his van, we started our jeep, and after about ten minutes of work we finally had a car that would start. “Thank you so much Peech!” we said.

“Keep in mind though that this doesn’t fix the problem,” he replied. “We can’t be sure that the battery will start tomorrow morning. You don’t want to find yourselves at Rabacca with a car that won’t start. It’s a lonely place and not many people go there, so it would be hard to find help. I really think you should stay in town tonight and talk to Curtis in the morning.”

He could tell that we weren’t too excited about doing that.

“If you really insist on starting your hike tonight, I think the only option for you would be to drive towards Rabacca, but stop along the main road at the turnoff for the trailhead. Park the car there. You’ll have to hike about forty minutes up the road to the trailhead but you guys are strong, you’ll probably be faster. And if the car doesn’t start in the morning you’ll be along the main road and you can flag someone down to jump start your car. People are nice here, someone will help you.”

Eric and I were surprised. Peech seemed to sense our determination to get started tonight. I looked at Eric. “Ok, we’ll do that,” Eric said.

“Just be sure you don’t use the air conditioning or the radio,” Peech warned, “you don’t want to drain that battery.” And with a hearty handshake and generous tip we bid farewell to our little welcoming party and pit crew and headed north.

THE MACHETE DUDE

“So, basically, what we gained this evening was simply the knowledge that the car might not start in the morning,” I said. We wound through the dark, curving, mountainous roads and after two hours finally arrived at a road sign that read “<- La Soufrière Trail.” “It must be a forty-minute hike from here to the trailhead I guess,” I said.

With the car still running we contemplated our options once again. It was like we were in the movie Speed where bus couldn’t go slower than 55mph or it would blow up. It was ten pm and we were both completely exhausted. We had woken up that morning at 2:30am in Trinidad, flown to Grenada, climbed the Grenada high point, then flown here. It was exceedingly tempting to just drive to the trailhead and park there. But we also wanted to be able to get a jump start in the morning if our car wouldn’t start.

“How about this,” I proposed, “we drive up to the trailhead tonight, drop off our water and camping gear. Then we drive back down and park here. Then we hike back up that road with minimal gear.” I didn’t have a backpack and didn’t want to have to carry a ten-pound water jug in my hand. “Ok, that works,” Eric answered.

We turned onto the (indeed very lonely) little road and headed up the hills and into the darkness. We passed through what appeared to be banana plantations with small mysterious little cinder block homes. About half-way up we had to slam on the brakes as a shirtless dude wielding a machete leaped out of the road. Apparently he had been sleeping in the road after a long day of work. I dreaded the point during our hike up that we’d have to pass that dude again without the protection of our car.

At long last we pulled into a parking lot that proclaimed itself as the trailhead for La Soufrière. We ditched our heavy stuff in the bushes and reluctantly dragged ourselves back into the car. We paused for a moment. “Man, it’s awfully tempting to just turn the car off right now, isn’t it?” I said. “Yep,” Eric answered. We sat there with the car running, staring off into the jungle. With a sigh, we came back to reality. “Well we don’t want to be stuck here, do we?” I said. “Let’s get this over with.”

In twenty minutes we were back at the bottom and with some momentary hesitation we finally turned the car off. We grabbed what few possessions we had left and began our painful trudge up that same road by the light of headlamp. I should have enjoyed the pleasant little night hike through the palm trees, with the sound of the crashing waves of the Atlantic in the distance, but the thought of the machete-wielding dude made me uneasy. If that dude had nefarious intentions we were sitting ducks. He could be waiting in the bushes, ready to spring upon us. I picked up a small palm frond and held it tightly in my hand. It obviously wouldn’t be any match for a machete, but at least it had the shape of one, so perhaps in the darkness the machete dude might mistakenly think we were armed.

Halfway up the road a quick flash caught the corner of my eye. I immediately froze, clenching the palm frond tightly. All my muscles tensed. I waited for the sound of footsteps and the whoosh of a machete. Silence. I slowly turned my gaze in the direction of the flash and saw two big eyes looking at me from ten feet away, illuminated by the reflection of my headlamp. Gulp. But something in the eyes seemed a little strange. They were spaced awfully wide for a person. No, that can’t be a person, I thought. Soon I could see the outline of some stubby horns and I knew what type of creature I was facing: it was the abominable jungle cow.

“Why’d you stop,” Eric asked. “Well there’s a cow here,” I answered with a voluminous sigh of relief. We nodded to the cow and kept walking.

A CONCRETE MATTRESS

At last we arrived at the La Soufrière trailhead at 11:15pm. Now things were once again under our control. It was us versus the mountain, with no people or machines between us. But before the big battle we needed a good rest. In Trinidad and Grenada, with such tiny backpacks our sleeping gear had already been absolutely minimal. Now, without my backpack, our gear was as bare-bones as you could get. But with a rainless sky and air temperature of 65F our margin for error was generously large. We found a nice little picnic pavilion and rolled out our tarp onto the concrete. I wrapped up in Eric’s spare poncho for warmth and fell asleep within minutes. The hard concrete wasn’t exactly comfortable but we were just so dang tired that it didn’t matter.

THE CLIMB

Now we’ve finally arrived at part of this story where we climb the mountain.

We knew that we had a long day ahead of us, we just didn’t know at the time how long it would be. So we got up with the rest of the avian jungle wildlife at 6:30am and scarfed down a quick breakfast of bagels and granola bars. We stashed in the bushes what little spare gear we had and hit the trail. It was so hot and humid that we took off our shirts within minutes. I felt like I was missing something. My only gear consisted of the thin swimming trunks and crocs I was wearing along with a little black stuff sack that contained my GPS, camera, and cell phone. It was the most ultra light I had ever hiked. Meanwhile Eric carried a little food and water in his backpack.

We’d read a trip report from some Coloradans that the hike had taken them just two hours round-trip. We already knew that our hike would be longer because we figured that they probably stopped just short of the actual high point, which of course was our destination. La Soufrière is a huge volcano that forms the entire northern half of the island. At the top of the volcano is a massive one-mile wide caldera. Meanwhile our research showed that the La Soufrière’s highest point was located about a half-mile from the crater rim. For our intended route, on the GPS we’d simply drawn a straight line from the crater to the summit, and assumed that the going would be easy.

As we climbed, the trees became shorter and shorter and the fog grew denser. After an hour the GPS indicated we were nearing the crater rim. The trail began to level out and suddenly I noticed that fifty feet in front of me the trail vanished into fog. I got the impression that we were close to the edge of the world. As I drew closer to the edge I inched forward more slowly and all of a sudden a thousand foot drop-off materialized. I gasped at the enormity of the sight below me.

LA SOUFRIÈRE

In front of and below us was La Soufrière’s gaping, smoldering, mile wide caldera. I turned my head left and right as far as it would go and the caldera was so gigantic that I still couldn’t see the whole thing. From the crater rim it was a thousand-foot drop to the crater’s floor and it appeared that there was no easy way down. In the bottom of the crater was an annular lush valley surrounding a gigantic, black, smoldering pile of rock that was probably only a few decades old (the last eruption was in 1979). There was even a small lake at the bottom. We could only speculate how the water drained out.

We had read descriptions and seen photos of this crater but no 2D representation could justly capture the magnitude and magnificence of the scene before us. We guessed now why so many people get to this point and turn around, claiming they’ve been to the “summit” of La Soufrière: 1) the view at this point is probably the best view of the mountain you’ll get on a cloudy day and 2) lots of people are probably acrophobic and don’t want to hike any farther.

We could also begin to guess why everyone else hires a guide. We had heard that there was only one “easy” way down into the crater, and you reached it by hiking clockwise along the crater from our location. We’d heard that the route down was steep but there’s a thick rope you can grab onto. If you’re afraid of heights the prospect of walking ten feet away from a thousand foot drop might be intimidating. Also, we figured that the descent point on the ridge might be hard to find. So it might indeed be reasonable to hire a guide. But not for us. We didn’t need a guide to tell us to stay away from the edge, and we could probably find the rope on our own.

For now, we would stick with the plan to hit the high point first, then on the way back maybe we’d try to find the way down into the crater if time permitted. It was just 8am so we figured we still had plenty of time. According to the GPS we were just 1.3 miles line-of-sight (LOS) from the summit. Piece of cake, right? The trees seemed short enough that even if there wasn’t a trail the bushwhacking would probably be no big deal.

TO THE SUMMIT

We turned right and headed counterclockwise along the crater rim towards the high point. The trail gradually petered out and brought us to the shore of a small and unexpected lake. “That’s weird, this wasn’t visible in any satellite photo,” I said. We had gotten a brand new Garmin GPS two weeks earlier that was capable of storing satellite photos and even our own custom maps. So in most places (in the US as we later found out) the resolution is so good that you can zoom in and see individual trees. But as we zoomed in our location it was completely white – all clouds. “I bet so few people are interested in satellite photos of this area and it’s always so cloudy that nobody’s able to get a clear shot of this mountain,” I said.

We skirted the lake and walked up to a low rise in the bushy hills. “Hmm, there should be a big old mountain behind those clouds,” I said. The GPS indicated we were just a half-mile LOS from the top. We watched as the clouds wafted through the high plateau. Soon we noticed a small gap coming and looked intently towards the mountain, ready to take photos.

The cloud gap passed slowly by, revealing the giant sleeping behind it. Our jaws dropped. For a moment we were speechless. “Uh, well one thing I can tell you is that we ain’t going straight up that,” I said. From this side the mountain appeared as an insurmountable fortress. As we gazed from bottom to top the steep jungle slopes blended into dark, sheer volcanic cliffs. As our astonishment abated we got to work. We knew this could potentially be one of our only clear views of the mountain that day. This could be our only chance to plan a route so we had better get a good look at that mountain, we thought.

We snapped a bunch of photos then began our discussion. It was obvious that from here on out that there wouldn’t be any trail. We were completely on our own. It was at this point that our excursion transformed from a simple day hike into a full-fledged mountain adventure. It was actually kind of thrilling. For a moment we felt like we were back in the California Sierra Nevada, planning a route up some 14’er. Here in St Vincent, however, there wasn’t snow and talus to navigate around, it was jungle and waterfalls.

“See that little gulley there, next to that cliff and above those trees?” I said to Eric, “I think that’ll go.” “I don’t know,” he replied, “that’s pretty steep, what about down there?” “I don’t think so, those trees are probably pretty dense,” I answered. After some back and forth we soon we had a plan worked out. There weren’t too many features to refer to, so it wasn’t even clear that we were both talking about the same route, but with mixed feelings of excitement and uncertainty we set out towards the first obstacle.

THE BARBED WIRE JUNGLE

We were entering uncharted territory. We could very well be the first people who’ve ever taken this route, we thought. Judging by the tree top heights the terrain seemed pretty flat so we made a beeline toward the beginning of the route. We began walking through dense waist-deep bushes, unable see what our feet were stepping on. After just a few steps though, to my horror the ground all of a sudden vanished from below me. I plunged into the bushes, falling about six feet before coming to a stop in some dense trees. I looked back and realized that I had just stepped into a little gulley. I yelled back to Eric, cautioning him to watch out for this trap.

I extricated myself from the bushes, thankful that at least I had my shirt on. My legs and arms were already getting cut up and I worried about what kinds of interesting little jungle plants awaited us higher up (like Grenada’s razor grass). We realized that this was going to be much harder that we thought. Soon we were thrashing through super-dense bushes, not sure if we were stepping onto rock or branch or thin air.

“Bushwhacking” is a relative term. There’s the easy kind of bushwhacking, where the trees are spread apart, there’s no undergrowth, and you can walk without worrying about your eye getting poked out or your clothes or skin getting shredded. You can see many feet in front of you and can easily plan your route. It’s basically like hiking on a trail. I’ll call that Grade 1 bushwhacking. On the other end of the spectrum is Grade 10 bushwhacking, à La Soufrière. It can sort of be likened to swimming. Sometimes you’re standing, other times you’re on your belly, slithering through trees, not sure how far you are above the ground. It’s dark, wet, and you’re always getting tangled up with the fallen trees and dead bushes. You need to protect your eyes from branches with sunglasses, but with all the exertion and moisture they fog up quickly and you can see almost nothing. You come out of a dense thicket with uncountable slashes on your legs, and you recall feeling so many sharp pricks that it’s impossible to remember where each slash came from. It’s a veritable jungle of barbed wire. You’re worried that you might have to turn around, and your anxiety causes you to stop taking pictures. These are the moments that don’t get documented, the moments where you’re giving it 100% but still not sure that it will be good enough. You measure your speed in feet per minute, not miles per hour.

Once in a while we could crawl on top of some bushes and get a bit of a view where we were headed. We decided to aim for a gully where maybe the trees wouldn’t be growing so thickly. As we looked back on the route we had taken we realized that just by looking at the treetop heights the route appeared flat, when in reality the terrain was super rugged. The vegetation had effectively smoothed out the topography. Once in a while I’d take a step and realize that I was barefoot, that one of my crocs had fallen off. I’d dig desperately through the trees and finally locate it. This would definitely not be the place to lose your footwear. Each time I would reaffirm my condemnation of LIAT’s baggage handling.

Unfortunately the gulley presented its own challenges. We’d be walking up rocks and then would suddenly encounter a ten-foot waterfall and have to start bushwhacking again. It was excruciatingly slow going. But inch by inch we climbed.

THE CRUX

Eventually a big black rock emerged above us, and this was our cue to head right. I wasn’t sure, but I think I remembered that the apparent crux – the hardest part of the route – was nearby. I rounded the corner and there it was – the slope that we had been worried about. The thick jungle grass couldn’t mask its verticality. From afar it hadn’t seemed so vertical; we figured that if it had grass it must still be a gentle slope. But from up close it presented quite the obstacle. I began to second-guess our path. Had we turned too early? Maybe we should have followed that gulley a little farther? Maybe it’s less steep farther around that corner? Or maybe we should go back down that gulley and over to the easier route we had seen?

But at this point the prospect of turning back, of giving up a single one of our hard-earned inches, was as repugnant as the smell of my filthy jungle-mud/swamp-water pants. No, we weren’t turning around at this point. If we can just make it up this steep pitch, the promised land of easy terrain will be just beyond it, right?

With my muscles twitching I approached the wall. My adrenaline was pumping and I had somehow become a rock climber. From this perspective it was pretty obvious that we had fifteen feet of solid vertical climbing. I grasped the first tuft of thick jungle grass as close to the roots as I could get and pulled myself up. As I climbed, each grass clump started out as a handhold and then became a foothold. With a firm tug I tested each plant before entrusting any weight to it, but still I felt that at any moment one of the clumps would pull out of the thin soil. Fortunately the trees and bushes and grass below were so dense that a fall probably wouldn’t be a big deal, just a thrill and an inconvenience. Nevertheless I clenched the grass tightly. I dug my hand in as deep as it would go and tried to grab each clump by the deepest roots.

With my pulse sky high and fight-or-flight response activated I wriggled up through the grass and with a final pull I was at the top. Even though the slope above was still probably a 45 degree angle it felt pretty darn flat. With plenty of branches to hold onto I anchored myself in place and waited for Eric. “I’m at the top!” I yelled, “and it looks like this route will go!”

Finally, Eric emerged over the lip and we paused to catch our breaths. I tried to peek over the pitch we had just climbed but couldn’t see over the grass. We had just free-soloed a fifteen-foot vertical pitch by holding onto jungle grass. We looked back on our route in the valley below. It had taken us an hour to cover just a quarter-mile. But at this point we felt like we could practically spit on the summit because the ridge was in sight and it didn’t look like there was any funny business in between. “Well I can tell you one thing,” Eric said, “we’re not taking the same route down.”

THE SUMMIT RIDGE

After another five minutes of moderate Grade 5 bushwhacking we had gained the ridge. To our amazement (and delight) we discovered an overgrown user trail along the ridge. Normally we’d have been disappointed to see this sign of man so near the top after so much of our own hard work. Normally we’d be disappointed that someone else had been here before. But today our only emotion was relief. This meant that not only was there a trail to the top, but moreover there was a trail down. If the trail was followable at the summit it’d certainly be followable farther down the mountain. Who knows where it led but it’s surely be easier and safer than the route we had taken up.

With victory in sight we turned right on the ridge and headed east. As I mentioned before, there had been some uncertainty in the actual summit location and elevation. Several points along the ridge all seemed to be within a few feet of elevation of each other [reference: Google Earth]. But with a trail to follow we’d have the liberty of visiting all the candidate summits and could determine which one was the actual high point.

We reached the top of the first local maximum (4032ft) but it was obvious that the next one was taller. When we gained the second summit (4056ft) we noticed that the trail fizzled out. Now it certainly seemed that this was tallest but we couldn’t be sure about the third summit. To make it official, we headed towards the third summit. After some Grade 4 bushwhacking we reached the third local maximum, elevation 4007ft. Beyond the third summit the ridge kept dropping. So we turned around, backtracked to the second local maximum (well I guess you could call it a global maximum then, for the country at least), and found ourselves, for the second time, on the roof of St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

At that moment, if you don’t count people in airplanes, and you assume that nobody was hiking up the high points in Guadeloupe, Martinique, and Dominica, the closest higher people were probably in Venezuela, 275 miles away. Not quite as good as on Denali, we thought, but pretty good nonetheless.

Now it was time for the summit rituals. We had a well-established routine on the state high points: photos of both of us with raised arms, juggling photos, jumping photos, and the collection of a small rock; but for country high points the customs had not yet been established. In addition to the photos we made it the new ritual of scarfing down some food on the summit because we were pretty darn exhausted. Surprisingly the time was only 10:57am, an elapsed time of just 3h57m. It felt like it was already late afternoon.

We lingered on top for a few more minutes, but surrounded by the foggy, viewless sky and with a lingering cloud of uncertainty about the route ahead of us we decided it was time to go. We couldn’t find a summit rock so I grabbed a little stick instead.

CRUISE CONTROL

Now the tide was beginning to reverse. Before, we had been climbing through the brush, working against gravity, defying the trees that tried to hold us back, getting farther away from civilization. Now we were on a trail, where people had walked before, gravity was helping us go down, getting closer to the trailhead. With a trail to follow we were almost on cruise control. Now it wasn’t exactly what many people would consider to be a “trail” but compared with what we had climbed through it was basically a road. With a trail to follow, the uncertainty in the route was almost completely erased. We just had to follow the trail and we’d get back to where we started.

The trail followed the ridge, passing a few sketchy no-fall zones, before leveling out at sort of a little col. Eric and I were starting to believe that maybe this trail kept going to the west side of the island, which was definitely not the side we wanted to end up on, so we decided it was time to leave the trail and resume our bushwhacking. We spotted a dry riverbed a quarter-mile away and knew that the going would be much easier down there. We looked for the shortest way down, held our breath, and plunged into the bushes. It was tough, but nothing compared with what we’d climbed through. Half an hour later we spotted the riverbed in front of us. “We made it!” I yelled. “Whoa, wait a minute,” Eric said, “it’s a ten foot drop to get down there.”

We did a little scouting back and forth and finally found a suitable route down that ended in a doable five-foot drop. At last we found ourselves in the middle of a huge dry riverbed. There were large boulders everywhere but with plenty of hard sand to walk on it was easy going. If the trail had been a “road” then this riverbed was an interstate. With all the wet vegetation we couldn’t figure out why the river bed was dry, but we sure appreciated it. Maybe it only fills up when there’s a hurricane, or a big storm? We knew we wouldn’t want to be down there during a flash flood.

CLIFFED OUT

Now at this point, just to make things interesting, it began to rain. Hard. Fortunately we found a little cave underneath a cliff and hunkered down inside it for some shelter. From the coziness of our cave we observed fifteen minutes of torrential downpour and noticed some trickles starting to form in the riverbed. I was expecting at any minute to see a big wall of water come roaring down the riverbed, but fortunately the rain eased up. We continued our little trek down the “interstate” and I soon noticed a curious topographic feature in front of me. It appeared that the riverbed, along with a small trickle of water, vanished into thin air. “Uh-oh, I think I know what that means,” I told Eric. We walked a little farther and found ourselves standing on the threshold of a 30ft waterfall/cliff.

“Well that’s just great,” I said to Eric. “Ain’t no way we’re downclimbing that.” We looked to the right side and saw a steep, but potentially downclimbable slope. We put our game faces on. It was bushwhacking time again. And this time it was back to the old Grade 10 junk we had swam through on the way up. But descending this stuff was whole different ball game.

As I slowly descended I went to plant my left foot on what I thought was level ground, but to my dismay there was nothing but air beneath it. Luckily I had been holding onto a strong tree, so in a split second I found myself swinging in thin air. “Eric, watch out for this,” I yelled back, “it’s a ten foot slope.” Unfortunately one of my crocs had fallen off and preceded me into the little abyss. So carefully I lowered myself into the bushes, trying not to put weight onto the bare foot, and was reunited with my little slipper. Most of the time the vegetation was a total nuisance, but on this occasion, I could hold onto some of the jungle grass to slow my descent. We made it past that obstacle and pushed on. Well, that’s ten feet down, we’ve got twenty to go before we’re back at the riverbed, I thought.

We descended a few feet more. I remember thinking, “I wonder what those last fifteen feet are going to look like, it’s getting pretty steep,” and all of a sudden air materialized once again beneath my feet. The brush was so dense that I wasn’t able to fall more than a few inches. Those fifteen feet were indeed very steep, but with the super dense brush we were able to ease ourselves down it safely. Finally we were at the base of the little waterfall. It was pretty much vertical and definitely not down-climbable.

We brushed ourselves off and kept walking. After a little boulder scrambling the riverbed began to widen out even more. “Wow, this is just too easy,” I said to Eric. “It’s about the only easy hiking we’ve done today.” We began to congratulate ourselves on finishing all the hard stuff. We just had to descend a little farther along the riverbed, then climb up to the crater rim, where there’d be a trail, and it’d be easy going again.

But a short while later we rounded a corner and found another little topographic feature to greet us: another waterfall. Fortunately there was only a little trickle of water in the riverbed so we could safely approach it closely to see what we were up against. But this wasn’t an ordinary little waterfall, this was a full-fledged cliff that dropped about sixty feet. We didn’t dare walk close enough to peek over.

Neither of us was too surprised, one more obstacle like this just seemed par for the course. “Well that’s too bad,” I said, “I don’t know how we’re getting out of this one. There’s cliffs on every side of us. There’s no way we’re walking around this one.”

BACK ON CRUISE CONTROL

“Why don’t we backtrack a little; it seemed like there was a little hill we could climb up back there,” Eric said. “Maybe we’re close enough to the crater that we can just walk up to it?”

With little optimism I agreed and we headed back up the riverbed. We came to the base of a steep – but doable – hill and started climbing. “Hmm, that’s weird,” Eric said, “this almost looks like a trail.” We climbed a little higher and lo and behold the trail opened up before us. Salvation! We noticed some discarded shoes and some trash on the trail and knew things would be getting easier. It’s not often that you rejoice at the sight of trash, but when it means that your life is about to get a lot easier it’s something to celebrate.

After another hundred feet of climbing we were back on the crater rim and back in business. We were now on the opposite side of the crater from this morning, so we’d need to hike halfway around it, but with a nice trail to follow it was almost trivial. Once again, just to make things interesting, it began to pour. This time it was very hard.

Eric and I threw on our meager rain gear and plodded on. Luckily it was still in the upper 60F’s so even though we were already completely saturated we were still warm. I looked down and began to contemplate the crocs that I was wearing. The most treacherous part wasn’t the lack of foot protection from branches, it was the lack of friction. The foot/croc friction and croc/ground friction coefficients were both pretty dismal, meaning that (especially on steep climbs) I was at risk for my crocs slipping with respect to the rocks and also my foot slipping out of my crocs. It was particularly treacherous during this torrential downpour.

HUMAN CONTACT

Eventually we spotted a curious sight in front of us. Other people! They were probably just as surprised as we were. We talked with the lead dude and found out they were part of a big group headed from one side of the island to the other. They had started at the same trailhead as us, were walking along the rim of the crater, and were planning to take another trail down to the leeward (west) side of the island. Everyone greeted us with a look of surprise. Maybe they were surprised we didn’t have a guide. Maybe they just didn’t expect to see anyone else trudging through this rainstorm high on this volcano. When we reached the end of their group we noticed three guide-looking dudes each carrying a big bucket. They gave us each a nod of approval. I figured that if anyone ever asked why we didn’t have a guide I’d just tell them that Eric was my guide and he’d say that I was his guide. We were guiding each other, I suppose.

Sometime while we were passing their group we noticed the big rope leading all the way down to the crater floor. It was steep, but not unreasonable. We were tempted to do it, but we had already attained our objective today and didn’t feel like pushing our luck any further.

For the rest of the hike our minds were on cruise control. True, the wind was howling, driving the torrential rain into our faces. I had to hold my hood on my head and at one point I finally brought my arm down; with it drained a full cup of water that had accumulated in the elbow area. But this was the easy part. We just needed to follow the trail in front of us and didn’t need to think too hard about much else.

BACK ON THE REAL TRAIL

We made it back to our starting point on the crater rim, completing a big loop. With my mind still on cruise control and with super-dense fog, we almost didn’t recognize the spot and nearly kept going. We took one last look into the crater and noticed twenty brand new waterfalls that had just formed. Some cascaded all the way from the crater rim, a thousand feet down to the floor. It was amazing to think that somehow all that water drained out underground.

We turned back onto the main trail and began the one-hour descent back to the Rabacca Trailhead. The tiny little trickles we had barely noticed on the way up turned into full-blown creeks on the way down. You could still jump over them but we couldn’t help but wonder what our “dry” riverbed looked like right about now.

The rain soon let up. After passing a few hikers near the bottom we suddenly heard a bunch of people talking up ahead and after climbing one last hill we were finally back at the start. As we emerged into the parking lot a news-reporter-looking-dude was pointing a video camera at us. I gave him a big thumbs-up.

“WE SAW IT ON WIKIPEDIA”

A woman with a microphone pulled Eric aside and began to interview him about the hike. Turns out they were interviewing everyone who had “climbed the mountain” that day. When it was my turn they asked me the standard questions about what mountain I had climbed. When we told them how difficult it had been and showed them the scars on our arms and legs they probably wondered “which mountain did they climb?” They probably couldn’t figure out just why our bodies were so torn up on such an easy trail. I’m not sure they understood the distinction I tried to make between “where the trail stops” and “where the highest point is.”

At the end they asked me how we had heard about this mountain. “We’re trying to climb several Caribbean country high points this week,” I said, “and we heard about La Soufière on Wikipedia.” I could tell that wasn’t the answer they were expecting.

But our hike wasn’t exactly over yet. We still had another three miles back to our car with a potentially-dead battery. We mingled with the people in the parking lot, trying to make friends, in the hopes that someone would give us a ride down, but it appeared that everyone was pretty comfortable hanging around and wasn’t prepared to leave anytime soon.

FINISHING WITH HONOR

“Fine, let’s just get out of here,” I said to Eric, “at least we can control what time we make it back to the car.” We packed up our meager belongings and trudged down the mountain. As we passed through a grove of palm and banana trees I noticed something yellow in the grass ahead of us. Bananas! We looked around to make sure nobody was looking and scarfed down the ripe ones. It was our first dose of fruit in the past three days. The clouds thinned and soon the sun came out. Our sunscreen was still in my lost backpack, but at this point I didn’t even care if I got sunburned, it would only be a minor discomfort compared with the gashes on my arms and legs.

We heard some cars speeding down the mountain and stuck out our hands and waved, hoping that they could drive us down the last mile of road. But the drivers simply waved back and kept going. “Maybe we should have stuck out our thumbs,” I said to Eric, “I wonder what the gesture for hitchhiking is down here?”

Finally at 3pm we arrived back at the car, finishing honorably under our own power. “What do you think the chances are that it’ll start?” I asked Eric, “I say it starts.” “I’ll say it starts,” Eric said. And indeed it started. “Now how do you like them apples?” he asked.

Along the two-hour drive back to the airport we got our little tour of St Vincent that we had missed in the darkness last night. As we drove along the spectacular coastline it was pretty clear that very few tourists come to this part of the island because there wasn’t a single hotel in sight.

We were back at the SVD airport by 5pm and knocked on the Avis door, ready to give Curtis a piece of our mind. Of course the door was locked. “Well it’s nice we flew in yesterday,” Eric said, “because there’s no way we could have done this mountain in eleven hours, especially with all this hassle with the rental car.”

VICTORY

After we got done unpacking we sat down next to our Suzuki and talked about what to do next. Mysteriously my backpack still hadn’t been found yet, but the LIAT reps said they were still looking for it. With five more hours before our flight to Barbados we still had plenty of time to see the sights and sounds of Kingstown. But we couldn’t muster the energy to stand up. We both sat there, in the parking lot, silent, with absolutely no desire to do anything. We were exhausted.

I thought about my contacts and rubbed my dry, red eyes and reluctantly came to the conclusion that I ought to find some contact solution before we left. My eyes couldn’t take much more of this. I summoned a taxi and we embarked on wild goose chase to pharmacies in downtown Kingstown that eventually came back fruitless. It appears that nobody in the country wears contacts.

We dragged our stuff into the airport, slumped down onto the benches, and awaited our flight. La Soufrière had taken a lot out of us, but today we had won. It had been at the expense of some blood, some sleep, and perhaps my backpack but we had won. We hoped that our next mountain, Mt Hillaby in Barbados, would fall more easily…

(Note: the backpack was finally located and repatriated two weeks later. I think US customs abandoned their inspection of its contents after they got a whiff of the one-gallon of two week old Grenadan jungle mud and swamp water infused into my clothes and shoes.)

(Note: email me [matthewg@mit.edu] or Eric [egilbert@mit.edu] if you’d like the GPS track for the hike)