| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |

| Vol.

XVII No.

1 September/October 2004 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

Some Reflections on Aspects of the

Undergraduate Education Policy

Recently, I have been giving more than my usual amount of thought to some aspects of undergraduate policy, in part because of issues that have arisen in teaching undergraduates, and in part because of my new role as a member of the Committee on Academic Performance (CAP). My goal in this note is to raise issues for discussion, and not to propose new policies, per se.

Possible Limits on Units

This past semester, I became aware of three different students in my class who were taking over 100 units each. Each of them asked to take the final exam a day later than the scheduled time, not because of conflicts, but because of the stress they were feeling. I was surprised to learn that there is no upper limit on the number of units taken by undergraduates after their first year. A limit on units would have helped in these situations because it would have lowered the stress level, and because it would have made it much less likely that these students would have asked for special privileges.

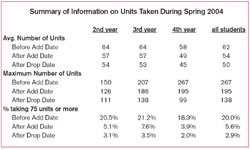

I was relieved to learn that taking such an excessive number of units is not widespread. I obtained data from the Registrar's Office for this article, and learned that only six students out of more than 3000 students (2nd year and higher) completed the semester with 100 or more units, and fewer than 3% of students completed the semester with 75 or more units.

The table summarizes the number of units taken by students.

Even if the problem of students completing the semester with very large subject loads is not common, it still may be worthwhile to consider limits on units, and to see whether it would be good educational policy. There are clearly pluses to permitting students to take as many units as they want. It shows that MIT values personal autonomy of students, and makes it easier for students to double major or to graduate in three years, or possibly both. It also avoids the need for mechanisms for limiting loads. But this liberty also comes with costs. It leads to students spreading their focus, and not giving the necessary attention to individual subjects. It increases the stress level. It negatively affects subjects that have group projects. Given the efforts and thought that went into limiting the number of units of first-year students, it is time to broaden that discussion to consider students after their first year.

| Back to top |

Drop and Add Dates

Relating to the issue of overload is the issue of when drop and add dates occur in the semester. It seems to me (perhaps because I am naïve), that the primary advantage of having drop dates so late in the semester (and later than the dates for comparable universities) is so that students have even more time to assess what their final grade in the class will be, and thus make a more informed decision on how to improve their GPA via selective dropping. Undoubtedly most undergraduates value this option; however, it seems to me to hinder education at MIT rather than aid it. It results in students deliberately taking overloads, and spreading their efforts too thinly. And, it encourages them to overly focus on the grade rather than on the education. And for instructors, it means that the class size is not dependable. It is also incompatible with six-week subjects, which is a time period that is becoming more common at the Sloan School.

Perhaps the greatest problem created by late dropping is the enormous waste of intellectual efforts and resources. Students waste enormous time in taking subjects for half a semester, and faculty and TAs waste enormous resources in teaching and grading these students. Given the scarce resources available, MIT should rethink when is an appropriate time for the drop date.

What is Acceptable Academic Performance?

When discussing academic performance of undergraduate students, we flag students who are taking fewer than 36 units, or who have a term GPA that is below 3.0. As I recall, this was the same criteria used when I arrived at MIT some 25 years ago, despite substantial changes in our undergraduate population and despite the possibility that there has been grade inflation. This may be a good time to review what is required for performance to be acceptable at MIT.

There are several issues to consider with respect to what constitutes acceptable academic performance. The first issue is what performance merits a warning.

Given the grade distribution at MIT, I propose that anyone with a GPA under 3.0 merits a warning as well as some other students taking too light a load. The second issue concerns the circumstances under which a student is required to withdraw from MIT. Here I suggest that MIT should consider being much stricter, and not permit students to continue at MIT with warnings in many different semesters. Personally, I view a cumulative GPA of less than 3.0 after the sophomore year as not meeting what should be MIT standards, and except in unusual circumstances, such students should be asked to withdraw. While I do not expect everyone to agree with me, I do believe it would be beneficial to discuss, as a community, what constitutes acceptable performance.

Low Achieving Students

All undergraduate students at MIT were great achievers in high school, and arrive here with great academic potential. But for a variety of reasons, not all students have academic success after they arrive. Moreover, for a number of underachieving students, MIT is not only a source of constant stress and disappointment, but it can do serious damage to motivation and sense of self. This situation is made more complex because many students at MIT view a transfer as an admission of failure.

The MIT community needs to acknowledge the simple and obvious fact that some students will do better, be happier, and be more successful by transferring to another university. We need to challenge the widely held (and incorrect) view that a transfer out of MIT is an admission of failure. We at MIT are doing low achieving students (and some other students as well) no favor if we blindly let them continue at MIT without presenting academic counseling that includes alternatives.

I suggest that advice to students include thoughtful information about transfers to another university and advice concerning financial assistance. Furthermore, MIT should consider having one or two advising deans who specialize in transfers. And for those students interested in transferring, we should do our best to make sure that they can transfer to a university where they will be both happy and successful. In so doing, we would be serving these students quite well.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |