| Vol.

XXII No.

1 September / October 2009 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

MISTI Matches Students with International Work

and Research Opportunities

This month the Class of 2013 started classes at MIT and I thought back to my own freshman year in a Midwestern college. At the time, the outside world was a distant and troublesome speck on the horizon: my uncle had fought in the war in the Pacific; my relatives had died in the holocaust in Europe. The Cold War separated us from large stretches of the globe. My own greatest aspiration with respect to foreign countries was to make a summer trip to France. The only cars we saw on the streets, and the only products in the stores, were American. Today, by any economic or cultural or political standard one can conceive, the world is a wholly different place.

The globalization of the economy, the rise of major new industrial societies in Asia, the technological revolution that followed the silicon chip – all these have totally altered the international horizon of our students and faculty. The quality of their lives as citizens and as professionals will depend critically on understanding societies outside their own.

Success today as an engineer or a scientist or a manager takes the ability to access and create knowledge outside of national borders. It requires knowing how to build networks with colleagues in centers of rapid growth and innovation across the world.

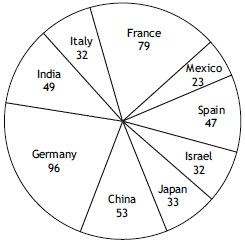

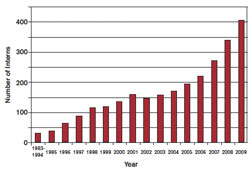

Educating students capable of learning and leading in global projects is the main objective of MISTI, the MIT International Science and Technology Initiatives. In 2009, MISTI sent over 400 undergraduates and graduate students to internships and research labs around the world. MISTI also provided close to $500,000 to MIT faculty for international projects and collaborations.

(click on image to enlarge)

MISTI’s approach to international education builds on MIT’s distinctive traditions of combining classroom learning and hands-on experience in UROPs, cooperative programs with industry, practice schools, and internships. In contrast to other universities’ internationalization programs that mainly involve study abroad, MISTI matches individual students with work or research opportunities in their own fields. The internships last three months to a year, and many of the students who go for a summer end up returning again for another stay. MISTI draws students from all over the Institute: 47% from the School of Engineering; 29% from the School of Science; 11% from Architecture and Planning; 7% from the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences; and 6% from Management.

An increasing number of MISTI projects are entry-level ones that offer second- and third-year students who might not yet be ready for a company or research lab assignment a chance to work abroad. These entry projects often involve teams of students adapting OCW (OpenCourseWare) materials for universities and high schools – in western China, India, Italy, and Germany. Students return from these experiences interested in doing more. Scot Frank (EECS ’09), for example, first worked on setting up OCW and iLab test equipment at a Chinese university and later returned to China as an intern with a Shanghai-based startup. Inspired by the experience of learning Chinese to prepare for MISTI, Frank and two fellow students created Lingt Editor, software for classroom-based language learning. Their company was recently featured as the “coolest college start-up” by Inc. Magazine.

| Back to top |

Here are a few other current examples – from the more than 3000 students MISTI has placed since it began by sending a handful of interns to Japan at the end of the eighties:

- Chemical Engineering student Nathalia Rodriguez worked on gene therapy for muscular dystrophy at Genopole, a French biotech cluster;

- Matthew Zedler, a Mechanical Engineering graduate, examined Chinese auto growth and energy at Cambridge Energy Research Associates in Beijing;

- Physics major Jason Bryslawskyj designed superconducting magnetic bearings for electric motors at Siemens in Germany. He wrote two patents at Siemens;

- Ammar Ammar, an EECS undergrad, designed and tested a Google/YouTube project at Google Israel;

- Civil and Environmental Engineering student Dina Poteau worked on water stress detection at the Technion in Haifa;

- Math major Elizabeth Theurer worked at Global InfraSys, an energy consulting firm in Gurgaon;

- Mechanical Engineering student Rachel Licht tested oil reservoirs for Total, a French energy company;

- Chemical Engineering major Christopher Love designed geothermal and solar thermal energy plants at ENEL, in Pisa, Italy;

- Brain and Cognitive Science major Shirin Kasturia explored healthcare technologies for the disabled at Innovaciones SocioSanitarias, Valencia, Spain;

- Management undergrad Ken Lopez worked on a Braille screen at Tecnologico de Monterrey in Cordoba, Mexico;

- Alexander Patrikalakis returned for several internships to Ricoh, in Japan, developing software for videoconferencing and 3D virtual realities.

Because international experience should be a core part of education – not a frill or an extra or a vacation trip for those whose families can afford it – MISTI makes these opportunities available at no additional cost to students. To participate in MISTI, however, a student must make a serious investment in learning about the country in which he or she wishes to intern. For entry-level MISTI activities, this involves at least one semester of course work on the country. For students seeking to be placed as regular interns, language courses are also required. MISTI students also participate in sessions led by MISTI staff on how to hit the ground running once they arrive and learn everything from how to buy train tickets, how to stay healthy, and how to work with colleagues.

Perhaps the most important part of these sessions is preparing students to discover that the same problem can be tackled in many different ways. A lab working on a project in France may have a very different problem-solving approach from an MIT lab. What looks like people wasting time drinking coffee and chatting may actually be the team exchanging ideas about next steps. If colleagues at work are polite, but non-committal, how do you get into the project? How can you figure out who makes the decisions in the organization and how ideas move ahead? “Teaching students not only about other countries, but about how to collaborate with peers abroad, is a primary mission of the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences,” says Dean Deborah Fitzgerald. MISTI is located in the Center for International Studies in SHASS.

The underlying idea in requiring students to learn about a country’s culture, language, history, and politics as prerequisite for an internship, is that context matters.

Erica Fuchs, a MISTI alumna who had internships in Germany and China and today is an assistant professor at Carnegie Mellon in the Department of Engineering and Public Policy, explained how critical it was for her research to see the ways in which the same technology plays out in different national settings. She looked at optoelectronic designs being developed for telecommunications and computing industries. The sponsoring companies for the research on which her dissertation was based wanted to understand the economic viability of a process technology called “monolithic integration.” Many of the firms were offshoring manufacturing, and Fuchs thought that location might matter for how efficient and profitable the new technology was. With funds from MISTI, she compared the newly established plants in China with ones in the U.S. She discovered that the new monolithically-integrated technology was the most economically competitive technology when manufacturing occurred in the U.S., but the monolithically-integrated design could not compete in the U.S. or developing East Asia against the old technology produced offshore. Fuchs says: “I would never have known the importance of manufacturing location for technology competitiveness if I hadn’t spent the extensive time I did through MISTI on the manufacturing shop floors of developing East Asia. I continue to emphasize the importance of this on-the-ground experience with all of my students today.” As we talk with students returning from the internships, their insights about the connections between context and science suggest that a unique form of learning is taking place.

EECS Department Head Eric Grimson observed that “to compete in today’s world, students have to appreciate global perspectives, global markets, different cultures, national priorities, nuances of communication in different languages, even the impact of social and religious norms on commercial and technological behavior.” EECS has been one of the most active departments in developing international internships in collaboration with MISTI.

The MISTI Global Seed Funds program provides yet another avenue for students to participate in global learning and knowledge creation. The program started last year with funding from the Office of the Provost for the internationalization of MIT research and education. Building on the model of the MIT-France Seed Fund, the program provides support for MIT faculty to launch international projects and research anywhere in the world and encourages them to involve students in the projects.

Of the 104 proposals received for the inaugural 2008 round, 27 were awarded $457,400 in funding. Faculty and research scientists from 26 departments across the Institute submitted proposals for projects in 42 countries. All awardees included undergraduate, graduate, or post-doctoral student participation.

Teams are using the grant money to jump-start international research projects and collaboration with faculty and student counterparts abroad. Funds cover international travel, meeting, and workshop costs to facilitate the projects. MISTI provides cultural preparation for students before their departure.

Today MISTI has 10 country programs: China, France, Germany, India, Israel, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Spain and – the latest – Brazil. New programs for Switzerland and for Africa are in the works. Each one of the country programs has a faculty member who serves as director and a full-time staff member as coordinator. Faculty leadership has been critical to the development of MISTI, and is drawn from departments across the Institute. Financing these programs involves a significant effort since funds have to be found for the students and for staff salaries. Today about a quarter of MISTI funds come from the Institute budget, and the rest is raised from gifts from alumni, corporations, and foundation grants. In a time of economic crisis and tough decisions about MIT’s priorities, some might wonder whether international learning is an activity we can afford. When we think about the shifts in the international economy, the emergence of high-powered centers of knowledge creation around the world, and the lives of our students over the next quarter-century, it seems like a necessity.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |