| Vol.

XXV No.

3 January / February 2013 |

| contents |

| Printable Version |

Concerns Over the Lack of Graduate Student Housing in the MIT 2030 Plan

Reprinted from the MIT Faculty Newsletter, Vol. XXIV No. 5, May/June 2012.

Prompted and motivated by the recent remarks of our President-Elect Rafael Reif when he noted, “A time of transition should also be a time for reflection – a time to assess where we are and where we are going,” I write today to discuss a very serious external threat to the way our Institute does business and how our community lives. Specifically, during my two years of service as the Graduate Student Council’s (GSC) Housing and Community Affairs (HCA) co-chair and a member of the Kendall Square Advisory Committee, I have developed significant concerns regarding the availability and accessibility of housing in surrounding regions as well as the higher order effects this will have on both the faculty and student communities at MIT.

To be very clear, our institute has shown significant commitment over the last decade with regards to its development of housing and support of our residential communities. In spite of these efforts, we now face unprecedented external market forces which have the power to irrevocably damage the ways and places in which we live. Thus, if we aim to be preemptive, rather than simply reactionary, in addressing the rapid changes that are increasingly taking place around us I propose here that we begin a collaborative conversation among students, faculty, staff, and administrators to set forth a vision for how our communities are defined and how to sustain our vibrant and invaluable residential community in an ever-changing housing market.

Although most of our statistics have come from studies of and on behalf of the graduate student community, I believe there exist far more commonalities between the faculty and graduate communities than we might otherwise acknowledge. For starters, approximately 62% of graduate students live off campus. This amounts to over 4,000 graduate students living primarily in the cities of Cambridge (59%), Boston (13%), and Somerville (11%) [percentages are of the total number of students who live off campus (4051). Numbers have an error of approximately +/- 2%] – the same neighborhoods in which a majority of faculty and staff currently reside. In addition to being neighbors, our demographics exist somewhere between undergraduates and faculty in terms of our international diversity (38% international), our marital statuses (31.6% with spouses or partners), and the number of households with dependents (~7% with dependents). In other words, we frequently reside where faculty live, with families, and in adjacent stations of life. Thus, I hope that some of my message may find resonance with many among the faculty.

To get straight to the point: It is our belief that, if left unchecked, the Cambridge rental housing crisis will not only have a profound effect on the quality of life of our many off-campus MIT community members, but it may also markedly impact our ability to attract the talent as well as maintain the level of productivity which fuel our academic pursuits.

For these reasons, I propose that an honest and frank conversation begin now in order to equip us strategically to manage the exogenous market as well as guide our current and future campus (and abutting land) development in the best interests of our communities.

Understanding Off-Campus Housing

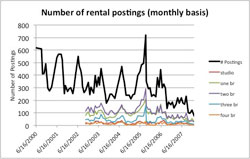

There are some who might cringe at my use of the word “crisis,” noting that the housing market is one which experiences different cycles and characteristic relaxation times than would the demand on other land resources for commercial or industrial uses. Though I would acknowledge that the housing market is indeed particularly complex and dependent on a number of inputs, I believe that all quantitative indicators available speak to an increasingly troubling trend: It is becoming nearly impossible to find, let alone afford, housing in the City of Cambridge. This issue of availability and affordability is poignantly demonstrated if we look at the aggregated listings of rentals in Cambridge and adjacent cities over the last seven years. The data, collected by the MIT Off-Campus Housing Office, shows a 75% decline in the average number of listings from a constant monthly sampling of the rental agencies in the area.

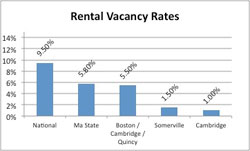

This trend is reinforced if we look at the rental vacancy rates in the regions surrounding MIT. Specifically, over the last decade, we have witnessed one of the most precipitous declines in vacancy rates in the Northeast. While MIT and real estate developers have expanded enrollment and commercialized the lands ensconcing MIT, respectively, the housing market lagged seriously behind. We are now faced with a situation in which demand is rapidly outpacing supply and those who we’ve spent so much time and money trying to attract to the City of Cambridge or MIT have little choice but to take up residence (and pay taxes) elsewhere. For comparison, the rental vacancy rates in Manhattan, and surrounding universities like Columbia and NYU, were hovering somewhere around 1.08% less than a year ago. In other words, it is likely just as hard now to find an apartment in Cambridge as it is in Manhattan.

(click on image to enlarge)

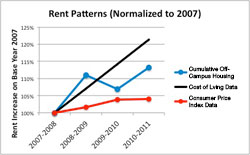

Unsurprisingly, with decreasing supply often comes increasing prices. If we normalize back to 2007 we can see the divergence between rent inflation in the immediate area (black and blue) and that of the surrounding three-state region of Boston-Brockton-Nashua as measured in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ CPI calculations (red).

(click on image to enlarge)

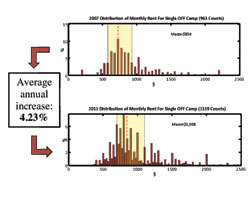

If we then look at the real prices paid by graduate students as measured in the 2007 and 2011 Cost of Living (CoL) Surveys conducted by the Office of the Provost/Institutional Research and jointly funded by the Graduate Student Council and the Office of the Dean for Graduate Education, we can tease out specific increases experienced by various subgroups or for different types of housing.

(click on image to enlarge)

From this we can see that rents for Single Off-Campus graduate students have increased an average of 4.23% per year over the last four years. This is significantly higher than the ~1% increases measured by the CPI data. As our Cost of Living and Off-Campus data sets are the most updated and complete publicly available housing data (and inform our Stipend Recommendation processes), we can say with a high degree of confidence that the development and gentrification of Cambridge has resulted in an environment that is not hospitable to a large proportion of our community. Thus, the discussion around whether one should use the word “crisis” is really a distraction from the quantifiable reality: Our community is increasingly unable to live in the vibrant nexus of technology and entrepreneurship that we have developed for them.

| Back to top |

Why should we care?

I would assert that living next to one’s place of work is not simply a luxury, but critical to research productivity in many fields core to MITs portfolio, such as the life sciences. To the first point, we know from numerous studies that graduate students not only work late, but also return home by foot and most frequently alone (approximately > 80% travel alone). The reason for this is that approximately 50% of graduates will depart from the lab after 7:00 PM, a time at which a vast majority of MBTA transportation options (Bus Lines 64, 68, and 85) connecting the surrounding neighborhoods shut down.

Put simply, the nature and expectations of many community members’ jobs – working late hours in the lab, office, design studio, etc. – is one which is not at all accommodated by the 9-to-5 infrastructure built for the nonacademic world. As a result, the ability to live a walking distance from campus is important to the safety, well-being, and quality of life of the graduate and faculty community.

In addition, the nature of research is changing to one in which research timelines are more fickle and demanding. If the NIH’s expansion over the last decade is any indicator, we’re likely conducting significantly more bio-related research at the Institute than we were several decades ago. With this fundamental shift in research focus has come a commensurate change in the way/times in which our population works. It is not unusual for graduates or young faculty to return to the lab after dinner repeatedly until sunrise in order to tend to some cell culture or growth. Thus we need to ask ourselves: Do we really expect these students and faculty to commute from Arlington or Watertown several times in a night or are we okay with the increasing number of futons we’ve begun to see in our labs and offices?

A final point worth mentioning is the effect that increasing housing prices and decreasing availabilities may have upon MIT’s competitiveness in attracting the best and brightest graduate students. First, we have to recognize the evolving expectations for housing which students are now carrying into their graduate school selection. Residences like Simmons and Maseeh Hall are excellent examples of how our drive to provide elegant, convenient, and fully equipped residences to undergraduates has grown in recent years, particularly in reference to the rest of our undergraduate housing portfolio. Similarly, we have recognized this trend and our recent graduate housing stock (SP, Ashdown, Warehouse) reflects this changing sentiment. Thus, prior to entering, graduates are being increasingly courted and coddled by their undergraduate institutions and as a result are unsurprisingly looking for more than a run-down two-bedroom shack in Watertown.

On top of this, we also have to be conscious of the fact that the graduate population, like that of the faculty, is increasingly international. For these groups, the ability to acquire either on-campus housing or nearby off-campus housing is of extremely high priority, particularly for those with no experience in our country, let alone the skills to apartment hunt in the surrounding cities. As a result, both our incoming domestic as well as international communities place extremely high value on the ability to live comfortably and close to campus. A laissez-faire approach to off-campus housing will not help and may jeopardize our ability to attract and retain the great minds that have built our reputation and will hopefully advance our mission in the future.

Conclusion

It would be uncharacteristic of the GSC to conclude this piece only having pointed to the problem and having made a couple of concerned remarks. Instead, I write this today as a call to action. With the MIT 2030 framework being opened to community input, an unprecedented degree of undergraduate-graduate-faculty communication, and the transition to a new administration at the Institute, I would like to end by calling upon the leaders of the student, faculty, staff, and administrators to begin candid and public discussions on what their vision for a residential community welcoming to the academic looks like and how we can work together to most effectively address the unprecedented external influences raised in this article. There is no better juncture than now to begin engaging both existing structures (e.g., ODGE/DSL, Institute Committees, Facilities) as well as potentially developing new bodies which further mobilize our members at a more grassroots level. Specifically, I propose the formation of a Student-Faculty-Administration working group whose charge would be to propose a vision for off-campus communities and outline actions to guide us in this uncertain and unkind market. Though this won’t be easy, no MIT-worthy challenge ever is. If, indeed, our greatest common strength is in our inspired experimentalism, then I see no reason why, in this case, we should shy away from the great living lab that is MIT.

| Back to top | |

| Send your comments |

| home this issue archives editorial board contact us faculty website |